Def. any "element from group 15 of the periodic table; nitrogen, phosphorus, arsenic, antimony and bismuth"[1] is called a pnictogen.

Some of the pnictogens like phosphorus, arsenic, antimony and bismuth, occur as metalloids.

Arsenopyrite on the right is 33.3 at % arsenic.

Nitrogens

The only important nitrogen minerals are nitre (potassium nitrate, saltpetre) and sodanitre (sodium nitrate, Chilean saltpetre).[2]

Ammoniacal nitrogens

Ammoniacal nitrogen (NH3-N) is a measure for the amount of ammonia, a toxic pollutant often found in landfill leachate[3] and in waste products, such as sewage, liquid manure and other liquid organic waste products.[4] It can also be used as a measure of the health of water in natural bodies such as rivers or lakes, or in man made water reservoirs.[5]

The typical output of liquid manure from a dairy farm, after separation from the solids is 1600 mg NH3-N /L.[6] Sewage treatment plants, receiving lower values, typically remove 80% and more of input ammonia and reach NH3-N values of 250 mg/L or less.[4]

Nitrides

A nitride mineral is a compound of nitrogen that occurs as a mineral where nitrogen has a formal oxidation state of −3 with a wide range of properties.[7]

Carlsbergites

{{free media}}Carlsbergite was first described in the Agpalilik fragment of the Cape York meteorite.

It is a chromium nitride mineral (CrN),[8] named after the Carlsberg Foundation that backed the recovery of the Agpalilik fragment from the Cape York meteorite.[8]

It occurs in meteorites along the grain boundaries of kamacite or troilite in the form of tiny plates,[8] associated with kamacite, taenite, daubreelite, troilite and sphalerite.[9]

In addition to the Cape York meteorite, carlsbergite has been reported from:[10]

- the North Chile meteorite in the Antofagasta Province, Chile

- the Nentmannsdorf meteorite of Bahretal, Erzgebirge, Saxony

- the Okinawa Trough, Senkaku Islands, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan

- the Uwet meteorite of Cross River State, Nigeria

- the Sikhote-Alin meteorite, Sikhote-Alin Mountains, Russia

- the Hex River Mountains meteorite from the Cape Winelands District, Western Cape Province, South Africa

- the Canyon Diablo meteorite of Meteor Crater, Coconino County, Arizona

- the Smithonia meteorite of Oglethorpe County, Georgia

- the Kenton County meteorite of Kenton County, Kentucky

- the Lombard meteorite of Broadwater County, Montana

- the Murphy meteorite of Cherokee County and the Lick Creek meteorite of Davidson County, North Carolina

- the New Baltimore meteorite of Somerset County, Pennsylvania

Osbornites

Osbornite is a very rare natural form of titanium nitride (TiN), found almost exclusively in meteorites.[11][12]

Qingsongites

Qingsongite is a rare boron nitride (BN) mineral with cubic crystalline form first described in 2009 for an occurrence as minute inclusions within chromite deposits in the Luobusa ophiolite in the Shannan Prefecture, Tibet Autonomous Region, China.[13] It was recognized as a mineral in August 2013 by the International Mineralogical Association named after Chinese geologist Qingsong Fang (1939–2010).[13] Qingsongite is the only known boron mineral that is formed deep in the Earth's mantle.[14] Associated minerals or phases include osbornite (titanium nitride), coesite, kyanite and amorphous carbon.[15]

Nitrites

Davinciite was discovered in hyperagpaitic (highly alkaline) pegmatite at Mt. Rasvmuchorr, Khibiny massif, Kola Peninsula, Russia, with associated minerals aegirine, delhayelite, nepheline, potassium feldspar, shcherbakovite, sodalite (silicates), djerfisherite, rasvumite (sulfides), nitrite, nacaphite, and villiaumite.[16]

Nitrates

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the molecular formula NO−

3 and a molecular mass of 62.0049 unified atomic mass units (u).

Gwihabaites

Gwihabaite [(NH4), K]NO3[17] is from Gcwihaba Cave, Botswana.[18]

K by XRF, N and H by gas chromatography, original total reported as 98.90%; corresponds to [(NH4)0.81)K0.19]Σ=1.00(NO3)1.00.[19]

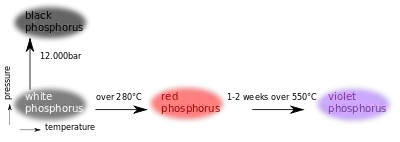

Phosphoruses

"Elemental phosphorus can exist in several allotropes; the most common of which are white and red solids. Solid violet and black allotropes are also known."[20]

"It would appear that violet phosphorus is a polymer of high relative molecular mass, which on heating breaks down into P2 molecules. On cooling, these would normally dimerize to give P4 molecules (i.e. white phosphorus) but, in vacuo, they link up again to form the polymeric violet allotrope."[20]

Phosphides

A phosphide mineral is a compound containing the P3− ion or its equivalent occurring naturally with many different phosphides known, and widely differing structures.[7]

Schreibersites

{{free media}}Schreibersite is generally a rare iron nickel phosphide mineral, (Fe,Ni)3P, though common in iron-nickel meteorites, where the only known occurrence of the mineral on Earth is located on Disko Island in Greenland.[21]

Another name used for the mineral is rhabdite that forms tetragonal crystals with perfect 001 cleavage; color ranges from bronze to brass yellow to silver white; density is 7.5 and a hardness of 6.5 – 7; opaque with a metallic luster and a dark gray streak; named after the Austrian scientist Carl Franz Anton Ritter von Schreibers (1775–1852), who was one of the first to describe it from iron meteorites.[22]

Schreibersite is reported from the Magura Meteorite, Arva-(present name – Orava), Slovak Republic; the Sikhote-Alin Meteorite in eastern Russia; the São Julião de Moreira Meteorite, Viana do Castelo, Portugal; the Gebel Kamil (meteorite) in Egypt; and numerous other locations including the Moon.[23]

Schreibersite and other meteoric phosphorus bearing minerals may be the ultimate source for the phosphorus that is so important for life on Earth.[24][25][26] Pyrophosphite is a possible precursor to pyrophosphate, the molecule associated with adenosine triphosphate (ATP), a co-enzyme central to energy metabolism in all life on Earth, produced by subjecting a sample of schreibersite to a warm, acidic environment typically found in association with volcanic activity, activity that was far more common on the primordial Earth, possibly representing "chemical life", a stage of evolution which may have led to the emergence of fully biological life as exists today.[27]

Phosphates

Phosphate minerals are those that contain the tetrahedrally coordinated phosphate (PO43−) anion along with the freely substituting arsenate (AsO43−) and vanadate (VO43−); chlorine (Cl−), fluorine (F−), and hydroxide (OH−) anions that also fit into the crystal structure.

Phosphate minerals include:

- Triphylite Li(Fe,Mn)PO4

- Monazite (La, Y, Nd, Sm, Gd, Ce, Th)PO4, rare earth metals

- Hinsdalite PbAl3(PO4)(SO4)(OH)6

- Pyromorphite Pb5(PO4)3Cl

- Vanadinite Pb5(VO4)3Cl

- Erythrite Co3(AsO4)2·8H2O

- Amblygonite LiAlPO4F

- lazulite (Mg,Fe)Al2(PO4)2(OH)2

- Wavellite Al3(PO4)2(OH)3·5H2O

- Turquoise CuAl6(PO4)4(OH)8·5H2O

- Autunite Ca(UO2)2(PO4)2·10-12H2O

- Carnotite K2(UO2)2(VO4)2·3H2O

- Phosphophyllite Zn2(Fe,Mn)(PO4)2•4H2O

- Struvite (NH4)MgPO4·6H2O

- Xenotime-Y Y(PO4)

- Apatite group Ca5(PO4)3(F,Cl,OH)

- hydroxylapatite Ca5(PO4)3OH

- fluorapatite Ca5(PO4)3F

- chlorapatite Ca5(PO4)3Cl

- bromapatite Ca5(PO4)3Br

- Mitridatite group:

Apatites

Fluorapatite, a sample of which is shown at right, is a mineral with the formula Ca5(PO4)3F (calcium fluorophosphate) that is the most common phosphate mineral occurring widely as an accessory mineral in igneous rocks, in calcium rich metamorphic rocks, as a detrital or diagenic mineral in sedimentary rocks, is an essential component of phosphorite ore deposits and occurs as a residual mineral in lateritic soils.[30]

At left is another fluorapatite example that is violet in color on quartz crystals.

Satterlyites

Satterlyite is a hydroxyl bearing iron phosphate mineral. The mineral can be found in phosphatic shales. Satterlyite is part of the phosphate mineral group. Satterlyite is a transparent, light brown to light yellow mineral. Satterlyite has a formula of (Fe2+,Mg,Fe3+)2(PO4)(OH). Satterlyite occurs in nodules in shale in the Big Fish River (Mandarino, 1978). These nodules were about 10 cm in diameter, some would consist of satterlyite only and others would show satterlyite with quartz, pyrite, wolfeite or maricite.

Holtedahlite, a mineral that was found in Tingelstadtjern quarry in Norway, with the formula (Mg12PO4)5(PO3OH,CO3)(OH,O)6 is isostructural with satterlyite (Raade, 1979). Infrared absorption powder spectra show that satterlyite is different than natural haltedahlite in that there is no carbonate for phosphate substitution (Kolitsch, 2002). Satterlyite is also structurally related to phosphoellenbergerite, a mineral that was discovered in Modum, Norway; near San Giocomo Vallone Di Gilba, in Western Alps of Italy (Palache, 1951); the minerals formula is Mg14(PO4)5(PO3OH)2(OH)6 (Kolitsch, 2002).

Turquoises

Turquoise at right is an opaque, blue-to-green mineral that is a hydrous phosphate of copper and aluminium, with the chemical formula CuAl6(PO4)4(OH)8·4H2O.

Arsenides

Realgars

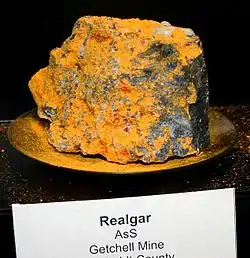

Realgar an arsenic sulfide mineral of 1.5-2.5 Mohs hardness is used to make red-orange pigment.

Realgar is a sulfide mineral. But, with equal atomic numbers of sulfur and arsenic, it may act as a pnictide.

This piece on the right is from the less well-known Royal Reward Mine of Washington.

Arsenates

Antimonides

Bismuthides

See also

References

- ↑ pnictogen. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 20 February 2015. Retrieved 2015-02-22.

- ↑ Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 407–09

- ↑ Aziz, H. A. (2004). "Removal of ammoniacal nitrogen (N-NH3) from municipal solid waste leachate by using activated carbon and limestone". Waste Management & Research 22 (5): 371–5. doi:10.1177/0734242X04047661.

- 1 2 Manios, T; Stentiford, EI; Millner, PA (2002). "The removal of NH3-N from primary treated wastewater in subsurface reed beds using different substrates". Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A 37 (3): 297–308. PMID 11929069.

- ↑ Glossary of terms for water health measurement at the Sabine River Authority of Texas

- ↑ Wastewater Treatment to Minimize Nutrient Delivery from Dairy Farms to Receiving Waters |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120323103103/http://ciceet.unh.edu/news/releases/fallReports/pdf/knowlton.pdf |date=March 23, 2012 a report for NOAA

- 1 2 Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-08-037941-9.

- 1 2 3 "Carlsbergite". Webmineral. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ↑ Carlsbergite in the Handbook of Mineralogy

- ↑ Carlsbergite on Mindat.org

- ↑ "Osbornite". Mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Osbornite Mineral Data". Mineralogy Database. David Barthelmy. September 5, 2012. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- 1 2 Qingsongite on Mindat.org

- ↑ Qingsongite: New Mineral from Tibet Hard as Diamond. sciencenews.org. August 5, 2013

- ↑ Pittalwala, Iqbal, International Research Team Discovers New Mineral, UCR Today, Aug. 2, 2013

- ↑ Khomyakov, A.P.; Nechelyustov, G.N.; Rastsvetaeva, R.K.; Rozenberg, K.A. (2012). "Davinciite, Na12K3Ca6Fe2+3Zr3(Si26O73OH)Cl2, a new K, Na-ordered mineral of the eudialyte group from the Khibiny alkaline massif, Kola Peninsula, Russia". Zap. Ross. Mineral. Obshch. 141 (2): 10–21. doi:10.1134/S1075701513070076.

- ↑ Handbook (2005). Mineral Handbook (PDF). Mineral Data Publishing. p. 1. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ↑ Martini, J.E.J. (1996) Gwihabaite - (NH4,K)NO3, orthorhombic, a new mineral from Gcwihaba Cave, Botswana. Bull. South African Speleological Assoc., 36, 19–21.

- ↑ (1999) Amer. Mineral., 84, 194.

- 1 2 "Allotropes of phosphorus". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 20 March 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-20.

- ↑ "Power behind primordial soup discovered", Eurekalert, April 4, 2013

- ↑ Schreibersite. Webmineral

- ↑ Hunter R. H.; Taylor L. A. (1982). "Rust and schreibersite in Apollo 16 highland rocks – Manifestations of volatile-element mobility". Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, 12th, Houston, TX, March 16–20, 1981, Proceedings. Section 1. (A82-31677 15–91). New York and Oxford: Pergamon Press. pp. 253–259. Bibcode:1982LPSC...12..253H.

- ↑ Report of U of A Extra-terrestrial Phosphorus

- ↑ "5.2.3. The Origin of Phosphorus". The Limits of Organic Life in Planetary Systems. National Academies Press. 2007. p. 56. ISBN 978-0309104845.

- ↑ Sasso, Anne (January 3, 2005) Life's Fifth Element Came From Meteors. Discover Magazine.

- ↑ Bryant, D. E.; Greenfield, D.; Walshaw, R. D.; Johnson, B. R. G.; Herschy, B.; Smith, C.; Pasek, M. A.; Telford, R. et al. (2013). "Hydrothermal modification of the Sikhote-Alin iron meteorite under low pH geothermal environments. A plausibly prebiotic route to activated phosphorus on the early Earth". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 109: 90–112. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2012.12.043.

- ↑ Mindat Arseniosiderite-Mitridatite Series

- ↑ Mindat Arseniosiderite-Robertsite Series

- ↑ http://rruff.geo.arizona.edu/doclib/hom/fluorapatite.pdf Mineral Handbook