A mineraloid is a substance that does not show or have crystallinity.

The image on the right is of lechatelierite which was created by a high voltage power line arcing to rocky soil.

Theoretical mineraloids

Def. "[a] substance that resembles a mineral but does not exhibit crystallinity"[1] is called a mineraloid.

Ebonites

Def. a "hard rubber especially when black or unfilled"[2] is called an ebonite.

Limonites

Limonite is an iron ore consisting of a mixture of hydrated iron(III) oxide-hydroxides in varying composition. The generic formula is frequently written as FeO(OH)·nH2O, although this is not entirely accurate as the ratio of oxide to hydroxide can vary quite widely. Limonite is one of the two principle iron ores, the other being hematite, and has been mined for the production of iron since at least 2500 BCE.[3][4] Although originally defined as a single mineral, limonite is now recognized as a mixture of related hydrated iron oxide minerals, among them goethite, akaganeite, lepidocrocite, and jarosite. Individual minerals in limonite may form crystals, but limonite does not, although specimens may show a fibrous or microcrystalline structure,[5] and limonite often occurs in concretionary forms or in compact and earthy masses; sometimes mammillary, botryoidal, reniform or stalactitic. Because of its amorphous nature, and occurrence in hydrated areas limonite often presents as a clay or mudstone. However there are limonite pseudomorphs after other minerals such as pyrite.[6] This means that chemical weathering transforms the crystals of pyrite into limonite by hydrating the molecules, but the external shape of the pyrite crystal remains. Limonite pseudomorphs have also been formed from other iron oxides, hematite and magnetite; from the carbonate siderite and from iron rich silicates such as almandine garnets. Limonite usually forms from the hydration of hematite and magnetite, from the oxidation and hydration of iron rich sulfide minerals, and chemical weathering of other iron rich minerals such as olivine, pyroxene, amphibole, and biotite. It is often the major iron component in lateritic soils. One of the first uses was as a pigment. The yellow form produced yellow ochre for which Cyprus was famous.[7]

Petroleums

Def. a "flammable liquid ranging in color from clear to very dark brown and black, consisting mainly of hydrocarbons, occurring naturally in deposits under the Earth's surface"[8] is called a petroleum.

Coal tars

Def. a "black, oily, sticky, viscous substance, consisting mainly of hydrocarbons derived from organic materials such as wood, peat, or coal"[9] is called a tar.

Def. a thick black liquid produced by the destructive distillation of bituminous coal is called a coal tar.

It contains at least benzene, naphthalene, phenols, and aniline.

Naphthas

Def. any "of a wide variety of aliphatic or aromatic liquid hydrocarbon mixtures distilled from petroleum or coal tar"[10] is called a naphtha.

Malthas

Def. a black viscid substance intermediate between petroleum and asphalt is called a maltha, or malthite.

Bitumens

Def. a black viscous mixture of hydrocarbons obtained naturally is called a bitumen.

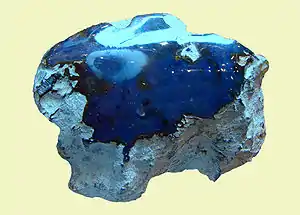

In the image on the right, bitumen occurs with lussatite, an opal.

Pitchs

Def. a "dark, extremely viscous material remaining in still after distilling crude oil and tar"[11] is called a pitch.

Asphalts

Def. a "sticky, black and highly viscous liquid or semi-solid, composed almost entirely of bitumen, that is present in most crude petroleums and in some natural deposits"[12] is called an asphalt.

Zietrisikites

Def. a natural, waxy hydrocarbon mineraloid is called a zietrisikite.

Ozocerites

Def. a natural dark, or black, odoriferous mineraloid wax is called ozokerite, or ozocerite.

Ambers

Def. a "hard, generally yellow to brown translucent fossil resin"[13] is called an amber.

Obsidians

An example of obsidian is shown on the right. Obsidian is a naturally occurring glass. Glass is an extremely viscous liquid.

Def. a naturally occurring black glass is called an obsidian.

Tektites

Def. "[a] small, round, dark glassy object, composed of silicates"[14] is called a tektite.

Opals

{{free media}}Def. a naturally occurring, hydrous, amorphous form of silica, where 3% to 21% of the total weight is water is called an opal.

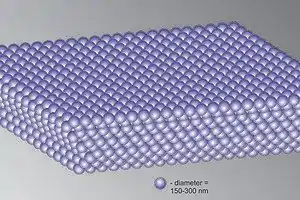

On the right are light blue opals from Succor Creek, Oregon, USA. On the left is an idealized diagram of the structure of opal consisting of spheres of silica arranged in an orderly manner.

On the lower left, by contrast to the light blue opals on the right, is massive dark blue and fluorescent banded opal.

Lechatelierites

Lechatelierite is amorphous SiO2, or silica glass.

Pearls

Def. a "shelly concretion, usually rounded, and having a brilliant luster, with varying tints, found in the mantle, or between the mantle and shell, of certain bivalve mollusks, [...] and sometimes in certain univalves"[15] is called a pearl.

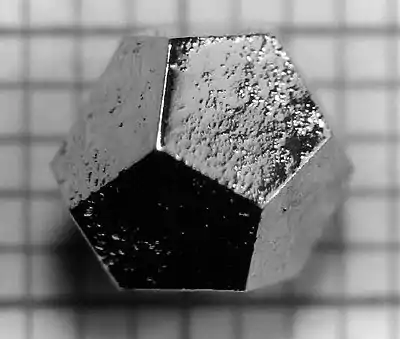

Quasicrystals

A crystalline substance that falls into a periodic pattern, or space group, in three dimensions, can be a mineral, or crystalline solid.

A quasicrystal consists of an ordered array of atoms or molecules without periodicity. They display a discrete pattern in X-ray diffraction but do not fall into any space group.

Hypotheses

- A mineral is a naturally occurring or naturally produced crystalline substance displaying space-filling periodicity.

See also

- Actinides (4 kB) (12 May 2019)

- Alkalis (12 kB) (10 January 2019)

- Minerals (107 kB) (18 October 2019)

- Mining geology (24 kB) (16 August 2019)

- Prebiotic Petroleum (74 kB) (12 May 2017)

- Petrophysics (40 kB) (7 November 2019)

- Thoriums (22 kB) (11 January 2019)

- Volcanic minerals (62 kB) (4 May 2019)

References

- ↑ mineraloid. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. April 20, 2011. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- ↑ Philip B. Gove, ed. (1963). Webster's Seventh New Collegiate Dictionary. Springfield, Massachusetts: G. & C. Merriam Company. p. 1221.

- ↑ MacEachern, Scott (1996) "Iron Age beginnings north of the Mandara Mountains, Cameroon and Nigeria" pp. 489–496 In Pwiti, Gilbert and Soper, Robert (editors) (1996) Aspects of African Archaeology: Proceedings of the Tenth Pan-African Congress University of Zimbabwe Press, Harare, Zimbabwe, ISBN 978-0-908307-55-5; archived here by Internet Archive on 11 March 2012

- ↑ Diop-Maes, Louise Marie (1996) "La question de l'Âge du fer en Afrique" ("The question of the Iron Age in Africa") Ankh 4/5: pp. 278–303, in French; archived here by Internet Archive on 25 January 2008

- ↑ Boswell, P. F. and Blanchard, Roland (1929) "Cellular structure in limonite" Economic Geology 24(8): pp. 791–796

- ↑ Northrop, Stuart A. (1959) "Limonite" Minerals of New Mexico (revised edition) University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico, pp. 329–333 }}

- ↑ Constantinou, G. and Govett, G. J. S. (1972) "Genesis of sulphide deposits, ochre and umber of Cyprus" Transactions of the Institution of Mining and Metallurgy 81: pp. 34–46

- ↑ petroleum. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 16 July 2014. Retrieved 2015-01-09.

- ↑ tar. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 5 January 2015. Retrieved 2015-01-09.

- ↑ naphtha. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 16 December 2014. Retrieved 2015-01-09.

- ↑ pitch. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 12 December 2014. Retrieved 2015-01-10.

- ↑ asphalt. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 20 October 2014. Retrieved 2015-01-09.

- ↑ "amber". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 19 December 2014. Retrieved 2015-01-09.

- ↑ tektite. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. August 31, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- ↑ Poccil (20 October 2004). pearl. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-07-19.

External links

{{Chemistry resources}}