THE

Best Hundred Books.

By the Best Judges.

Pall Mall Gazette "Extra"—No. 24.

Choose well, your choice is

Brief but yet endless.

Carlyle, after Goethe.

All rights reserved.]

[NEW AND REVISED EDITION.]

[Price THREEPENCE.

CONTENTS.

| PAGE | ||

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

1 | |

Mr. Lowell on the Choice of Books . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

2 | |

Carlyle on the Best Books . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

3 | |

Sir John Lubbock's First List . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

4 | |

Criticisms and Lists by the Best Judges . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

5 | |

Mr. Ruskin on the Choice of Books . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

8 | |

| PAGE | ||

Travellers' Libraries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

21 | |

The "Prison Test" in Books . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

22 | |

Sir John Lubbbock's Reply and Final List . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

23 | |

What Books are most Read . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

25 | |

Alphabetical List of Books Recommended, with Prices and Editions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

26 | |

INTRODUCTION.

THERE is no more delightful pastime than to lecture other people on the choice of books. Carlyle, in recent times, began the game, and since his Edinburgh address every lecturer has had his own select library to recommend. But the choice of books, if a pleasant pastime to the lecturer, is none the less an important matter for his audience, and Sir John Lubbock did well in selecting it for the subject of his inaugural address to the Working Men's College last month. Those who have seen the efforts made by the more intelligent working men and other uninstructed seekers after knowledge are well aware how many errors come from ignorance about the Best Books. There is something really pathetic, for instance, in the story of the Northumberland pitman who, after attending some science lectures, saved up his scanty money to buy a copy of Goldsmith's "Natural History," only to find when he took his treasure home that it was hopelessly antiquated. But the errors of choice made from carelessness are even greater than those made in ignorance; and hence no doubt it was that Sir John Lubbock, in giving the Working Men's College his list of the Best Hundred Books, added that "if a few good guides would draw up similar lists it would be most useful." Sir John Lubbock, like every other seriously minded and methodic man, had "often been astonished to see how little care people devoted to the selection of what they read." Ars longa, vita brevis; and with a view to neutralizing the inequality we determined to take up Sir John Lubbock's hint, and to invite all the best guides in England to place their clues to the bewildering labyrinth of books at the service of the public. The answers that we published from day to day created so much interest—both for the light that they threw on the idiosyncrasies of the writers and for the light that they gave to searchers after knowledge—that it became necessary to meet the continued demand for copies by this republication. We have included a few letters not hitherto published, as well as some additional matter, which, it is hoped, may enhance the value of this "Extra."

There is no doubt something bewildering at first sight in the multitude of counsellors and the striking diversity of their counsel. The total number of books included by one authority or another among the "best hundred" is, we find, considerably over 400, and there are surprisingly few books which appear in more than one of the lists. Now, there must be moderation in reading as in other good things; and the ordinary man will probably seek some halfway house between the "catholic taste" of Charles Lamb which excluded "all those volumes which no gentleman's library should be without" and the omnivorous appetite of Macaulay, who would master on a voyage to India what many men are labouring all their lives to skim. After all is said and done, we doubt whether Shakspeare's advice can be improved upon—

No profit grows where is no pleasure ta'en;

In brief, sir, study what you most affect.

We do not take it that the contributors to this little volume expect the general reader to master more than the whole of any one list, certainly not the sum of them all. Every one will study what he most affects, and the value of this collection lies, we venture to think, in this—that among the variety of good judges here gathered in judgment every reader will find one to advise him according to his taste. The golden rule in the choice of books is not to attempt to read the best books in every department of knowledge, but to be sure of reading the best in any province that you take for your own. In the hope of meeting this end, we have arranged all the principal books recommended by our contributors in alphabetical order (p. 26), and have affixed the price and other necessary particulars of the most accessible editions. This list has been specially revised for the present edition. Further, we thought it would be both interesting and suggestive to add to what people ought to read what as a matter of fact they do read. The librarians of some typical Free Libraries have kindly supplied us with the necessary information under this head (p. 25). On the question of the choice of books we are happy to be able to add an interesting paper by Mr. Ruskin (p. 8), and a hitherto unpublished letter by Carlyle (p. 3), and we have further taken the liberty of reprinting from the American journals he report of a lecture which Mr. J. R. Lowell delivered shortly before Sir John Lubbock gave his list. Mr. Lowell's lecture contained, it seemed to us, some of the wisest and wittiest things that have been said on the subject.

Mr. J. R. Lowell on the Choice of Books.

MR. J. RUSSELL LOWELL in his address at the dedication of the Free Public Library, Chelsea, Massachusetts, just before Christmas, said:—Have you ever rightly considered what the mere ability to read means? That it is the key that admits us to the whole world of thought and fancy and imagination, to the company of saint and sage, of the wisest and the wittiest at their wisest and wittiest moments? That it enables us to see with the keenest eyes, hear with the finest ears, and listen to the sweetest voices of all time? More than that, it annihilates time and space for us; it revives for us without a miracle the Age of Wonder, endowing us with the shoes of swiftness and the cap of darkness, so that we walk invisible like fern seed, and witness unharmed the plague at Athens or Florence or London, accompanying Cæsar on his marches, or look in on Catiline in council with his fellow-conspirators, or Guy Fawkes in the cellar of St. Stephen's.

There is a choice in books as in friends; and the mind sinks or rises to the level of its habitual society is subdued, as Shakspeare says of the dyer's hand, to what it works in. Cato's advice, "Consort with the good," is quite as true if we extend it to books; for they, too, insensibly give away their own nature to the mind that converses with them. They either beckon upward or drag down. And it is certainly true that the material of thought reacts upon the thought itself. Milton makes his fallen angels grow small to enter the infernal council room; but the soul, which God meant to be the spacious chamber where high thoughts and generous aspirations might commune together, shrinks and narrows itself to the measure of the meaner company that is wont to gather there, hatching conspiracies against our better selves. We are apt to wonder at the scholarship of the men of three centuries ago, and at a certain dignity of phrase that characterizes them. They were scholars because they did not read so many things as we. They had fewer books, but these were of the best. Their speech was noble, because they lunched with Plutarch and supped with Plato. We spend as much time over print as they did; but, instead of communing with the choice thoughts of choice spirits, and unconsciously acquiring the grand manner of that supreme society, we diligently inform ourselves, and cover the Continent with a network of speaking wires to inform us, of such inspiring facts as that a horse belonging to Mr. Smith ran away on Wednesday, seriously damaging a valuable carryall; that a son of Mr. Brown swallowed a hickory nut on Thursday; and that a gravel bank had caved in and buried Mr. Robinson alive on Friday. Alas, it is we ourselves that are getting buried alive under this avalanche of earthy impertinences! It is we who, while we might each in his humble way be helping our fellows into the right path, or adding one block to the climbing spire of a fine soul, are willing to become mere sponges saturated from the stagnant goose pond of village gossip.

One is sometimes asked by young people to recommend a course of reading. My advice would be that they should confine themselves to the supreme books in whatever literature, or, still better, to choose some one great author, and make themselves thoroughly familiar with him. For as all roads lead to Rome, so do they

likewise lead away from it; and you will find that, in order to understand perfectly and weigh exactly any vital piece of literature, you will be gradually and pleasantly persuaded to excursions and explorations of which you little dreamed when you began, and will find yourselves scholars before you are aware.

A library should contain ample stores of history. History is, indeed, mainly the biography of a few imperial men, and forces home upon us the useful lesson how infinitesimally important our own private affairs are to the universe in general. History is clarified experience; and yet how little do men profit by it! Nay, how should we expect it of those who so seldom are taught anything by their own? Delusions, especially economical delusions, seem the only things that have any chance of an earthly immortality.

A public library should also have many and full shelves of political economy; for the "dismal science," if it prove nothing else, will go far towards proving that the millennium will not hasten its coming in deference to the most convincing string of resolutions that were ever unanimously adopted in public meeting. It likewise induces in us a profound distrust of social panaceas.

I would have a public library abundant in translations of the best books in all languages; yet some acquaintance with foreign and ancient literature has the liberating effect of foreign travel. He who travels by translation travels more hastily and superficially, but brings home something that is worth having, nevertheless. Translations, properly used, by shortening the labour of acquisition, add as many years to our lives as they subtract from the processes of our education.

In such a library, the sciences should be fully represented, that men may at least learn to know in what a marvellous museum they live, what a wonder-worker is giving them an exhibition daily for nothing. Nor let art be forgotten in all its many forms; not as the antithesis of science, but as her elder or fairer sister, whom we love all the more that her usefulness cannot be demonstrated in dollars and cents. I should be thankful if every day labourer among us could have his mind illumined, as those of Athens and Florence had, with some image of what is best in architecture, painting, and sculpture, to train his crude perceptions and perhaps call out latent faculties. I should like to see the works of Ruskin within the reach of every artisan among us; for I hope some day that the delicacy of touch and accuracy of eye that have made our mechanics in some departments the best in the world may give us the same supremacy in works of wider range and more purely ideal scope.

Of voyages and travels I would also have good store, especially the earlier, when the world was fresh and unhackneyed, and men saw things invisible to the modern eye. They are fast sailing ships to waft away from present trouble to the Fortunate Isles.

To wash down the drier morsels that every library must necessarily offer at its board, let there be plenty of imaginative literature, and let its range be not too narrow to stretch from Dante to the elder Dumas. The world of imagination is not the world of abstraction and nonentity, as some conceive, but a world formed out of chaos by the sense of the beauty that is in man and the earth on which he dwells. It is the realm of might-be, our haven of refuge from the shortcomings and disillusions of life. It is, to quote Spenser, who knew it well, "the world's sweet inn from care and wearisome turmoil."

Carlyle on the Best Books.

An Unpublished Letter.

EXACTLY fifteen years ago a North-country lad who was seeking after knowledge in the midst of his work in a printer's office wrote to Carlyle for his advice on the best books, Those who have read Mr. Froude's life know already how full of encouragement and sympathy Carlyle was whenever he was appealed to in this way. This letter is no exception to the rule. With reference to one observation by Carlyle, it should be pointed out that the letter was written before Mr. Jowett "made Plato an English classic":—

5, Cheyne-row, Chelsea,

Feb. 14, 1871.

Dear Sir,—Your letter has pleased and interested me; and certainly I wish you progress in your ingenuous pursuit, which may be defined as the highest and truest for all men in all ranks of life. Evermore is Wisdom the highest of conquests to every son of Adam, nay, in a large sense, the one conquest; and the precept to every one of us is ever, "Above all thy gettings get understanding." Books are certainly a great help in this pursuit; but I know not if they are the greatest; the greatest I rather judge are one's own earnest reflections and meditations, and, to begin with, a candid, just, and sincere mind in oneself. Books, however, especially the Books of sincere and true-seeing men, are indisputably a great resource of guidance and assistance; and indeed are at present almost the only one we have left.

I have more than once thought of such a list as you speak of (for we all, in universities as well as workshops, labour under that difficulty, and in the each each of us has to pick his own way); but a good list of the kind would be extremely difficult to do; and would be both an envious and precarious one. Impossible to be right in all your judgments of Books; and still more impossible to please everybody with it if you even were! Perhaps I may try something of it some good day nevertheless.

For the rest, I can assure you that your choice of a Homer is perfectly successful: I reckon Pope's still fairly the best English translation, though there are several newer, and one older, not without merit; in regard to style, or outward ggrniture, neither Pope nor one of them has the least resemblance to rough old Homer; but you will get the shape and essential meaning out of Pope as well as another. In regard to Plato (Socrates didn't write anything; and he is known chiefly by what Plato and Xenophon say of him) your best resource will probably be Bohn's Classical Library (Bohn, York-street, Covent-garden), a readable translation at four or five shillings, which any country bookseller can get for you on order: and, indeed, I may say, in regard to all manner of books, Bohn's Publication Series is the usefullest thing I know; and you might as well send to him for a catalogue, which, doubtless, he would willingly send you for the postage stamp. As to English History, Hume's is universally regarded as the best; but perhaps none of them can rigorously be called good; and you will be sure to take the first book you can come at, and to read that with all your attention, keeping a map before you, and looking round you on all sides; especially looking before and after for chronoiogy's sake,—upon which latter at least, if not upon various other things, you may find it useful to take notes. Pinkerton's Geography, even the 8vo abridgment (still more the 2 vol. 4to original), is a useful book in such studies. In Political Economy I consider Smith's "Wealth of Nations," which is the beginning of all the books since, to be still, by many degrees, the best, as well as the pleasantest to read; and in regard to that of "Political Economy," nay even to that of Plato, &c., &c., you must not be surprised if the results arrived at considerably disappoint you; and sometimes, though also sometimes not, completely deserve to do so.

Wishing you heartily well, and recommending silence, sincerity, diligence, and patience as the grand conditions of every useful success in your pursuit, I remain, yours sincerely, T. Carlyle.

I.—SIR JOHN LUBBOCK'S FIRST LIST.

(As Classified by the Pall Mall Gazette, Jan. 11, 1886.)

WE must begin by giving the list which we originally compiled from the report of Sir John Lubbock's lecture, and which formed the basis of the inquiries we addressed to our contributors. It is right, however, to say at once that Sir John Lubbock (to whose uniform courtesy we have been greatly indebted) wrote soon after our list had been published that he did not in his lecture mention quite the whole Hundred Best Books, of which he subsequently gave a complete list in the Contemporary Review. "I did, however," he added, "recommend 'Don Quixote' and Epictetus. I shall be glad also if you will allow me to observe that I excluded (1) works by living authors, (2) science, and (3) history, with a very few exceptions which I mentioned rather in their literary aspect."

Non-Christian Moralists.

Marcus Aurelius |

"Meditations. |

Confucius |

"Analects.' |

Aristotle |

"Ethics.' |

Mahomet |

"Koran." |

Theology and Devotion

"Apostolic Fathers" |

Wake's Collection. |

St. Augustine |

"Confessions." |

Thomas à Kempis |

"Imitation." |

Pascal |

"Pensées." |

Spinoza |

"Tractatus Theologico-Politicus," |

Butler |

"Analogy." |

Jeremy Taylor |

"Holy Living and Holy Dying." |

Keble |

"Christian Year." |

Bunyan |

"Pilgrim's Progress." |

Classics.

Aristotle |

"Politics." |

Plato |

"Phædo." "Republic." |

Æsop |

"Fables." |

Demosthenes |

"De Coronâ." |

Lucretius.

Plutarch.

Horace.

Cicero |

"De Officiis." "De Amicitiâ." "De Senectuie." |

Epic Poetry.

Hiner |

"Iliad" and "Odyssey," |

Hesiod.

Virgil.

Niebelungenlied.

Malory |

"Morte d'Arthur." |

Eastern Poetry.

"Mahabharata" "Ramayana" |

Epitomized by Talboys Wheeler. |

Firdausi |

"Shahnameh" (Translated by Atkinson). |

"Sheking" (Chinese Odes).

Greek Dramatists

Æschylus |

"Prometheus," "House of Atreus," Trilogy, or "Persæ." |

Sophocles |

"Œdipus" Trilogy. |

Euripides |

"Medea." |

Aristophanes |

"The Knights." |

History.

Herodotus.

Xenophon |

"Anabasis." |

Tacitus |

"Germania." |

Thucydides.

Gibbon |

"Decline and Fall." |

Voltaire |

"Charles XII." or "Louis XIV." |

Hume |

"England." |

Grote |

"Greece." |

Philosophy.

Bacon |

"Novum Organum." |

Mill |

"Logic" "Political Economy." |

Darwin |

"Origin of Species." |

Smith |

"Wealth of Nations" (selection). |

Berkeley |

"Human Knowledge." |

Descartes |

"Discours su la Méthode." |

Locke |

"Conduct of the Understanding." |

Lewes |

"History of Philosophy." |

Travels

Cook |

"Voyages." |

Darwin |

"Naturalist on the Beagle." |

Poetry and General Literature.

Shakespeare.

Milton.

Dante.

Spenser.

Scott.

Wordsworth.

Pope.

Southey.

Longfellow.

Goldsmith |

"Vicar of Wakefield." |

Swift |

"Gulliver's Travels." |

Defoe |

"Robinson Crusoe." |

"The Arabian Nights."

Boswell |

"Johnson." |

Burke |

Select Works. |

Essayists:—

Addison.

Hume.

Montaigne.

Macaulay.

Emerson.

Molière.

Sheridan.

Carlyle |

"Past and Present." "French Revolution." |

Goethe |

"Faust." "Wilhelm Meister." |

Marivaux |

"La Vie de Marianne." |

Modern Fiction.

Selections from—

Thackeray.

Dickens.

George Eliot.

Kingsley.

Scott.

Bulwer Lytton.

CRITICISMS AND LISTS BY THE BEST JUDGES.

II—H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, Politicians, &c.

WE begin the criticisms on Sir John Lubbock's list with the letter of the Prince of Wales, whose interest in the advancement of letters is well known, and who courteously found time to answer our questions.

H.R.H. THE PRINCE OF WALES.

Sandringham, Norfolk, Jan. 15, 1886.

My dear Sir,—I am desired by the Prince of Wales to thank you for your letter of the 11th inst., and to assure you that he appreciates very sincerely the compliment which you are so good as to pay him in requesting him to draw up a catalogue of books which might seem to him to be the most conducive to a healthy mental state. The application is one which would require much time and thought to answer satisfactorily, and the Prince speaks, therefore, with diffidence when he expresses an opinion that the list suggested by Sir John Lubbock could hardly be improved upon. His Royal Highness would, however, venture to remark that the works of Dryden should not be omitted from such an important and comprehensive list.—I beg to remain, yours truly, Francis Knollys.

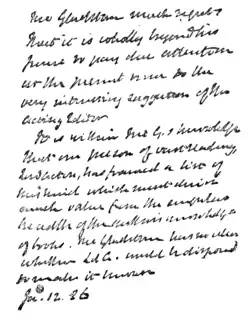

MR. GLADSTONE.

The late Prime Minister is like the Prince of Wales in at least one respect—both of them are men of encyclopædic interests. Mr. Gladstone is well known to be an omnivorous reader, and he was naturally among the first of the judges to whom we forwarded Sir John Lubbock's list. Mr. Gladstone replied by return of post, and on a post card, as follows:—

The general public were able to form some idea of Lord Acton's "vast reading" from his review of George Eliot's Life some months ago in the Nineteenth Century, and we hoped to have been able to lay before our readers the information to which Mr. Gladstone so properly attaches such high importance. Unfortunately, however, Lord Acton was abroad, and our letter did not reach him until after a considerable interval. He very kindly promised to write to us on the subject, but his letter has not reached us in time to be included in the present issue.

MR. CHAMBERLAIN.

Sir,—In reply to your inquiry I am directed by Mr. Chamberlain to say that he does not think he could greatly improve the list of books already submitted by Sir John Lubbock. He would, however, inquire whether it is by accident or design that the Bible has been omitted.—I am, yours obediently, Wm. Woodings.

PROFESSOR BRYCE, M.P.

The new Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs has made himself so much of a political reputation in these latter years that we include him under the head of politicians. People are almost beginning to forget that he first made his reputation by a book ("The Holy Roman Empire"), and that he is still a University professor. Mr. Bryce wrote to us as follows:—

I am sorry to have been prevented by an accumulation of work from replying sooner to your request for a list of books "necessary for a liberal education," such as you have had from Sir John Lubbock. I have not time to furnish you with such a list, which would need a good deal of consideration, and would be quite different according as one assumes the person to be "liberally educated" to possess a wider or narrower knowledge of languages. There are books well deserving to be read in the original which are much less worth reading in translations.

However, I give you some additions to and criticisms on Sir John Lubbock's list which occur to me. I have not seen the remarks of your other correspondents, except Mr. Ruskin's. In Greek poetry Pindar ought to be substituted for Hesiod. In Greek philosophy Aristotle's Rhetoric and Poetic ought not to be omitted. Of Cicero it would be much better to have some Orations than the Offices or Old Age. St. Augustine's "De Civitate Dei" is indispensable. Perhaps no book ever more affected history. "The Icelandic Sagas," or some of them, ought to be added. Most of the best have been translated, such as "Njál's Saga," "Grettir's Saga," and the "Heimskringla." The poems in the "Elder Edda" (now admirably translated in Vigfusson and Powell's "Corpus Poeticum Boreale") ought also to find a place. For travels, add Marco Polo; for history, Machiavelli's "Prince." In Italian poetry Ariosto and Leopardi should come in. The "Lusiad" of Camoens is one of the finest examples of a poem in the grand style, and not the less interesting because the only work of Portuguese genius whose fame has overpassed the limits of its country. Montesquieu's "Esprit des Lois" is indispensable. So is "Candide." In modern fiction, "Les Misérables" and "The Scarlet Letter" may well replace Kingsley and Bulwer; the modern poets Keats and Shelley surely rank above Southey and Longfellow. Whether you put anything in its place or not (for example, Kant's "Kritik der reinen Vernunft," or Hegel's "History of Philosophy"), Lewes's "History of Philosophy" should be struck out,

THE LORD CHIEF JUSTICE OF ENGLAND.

Lord Coleridge wrote to us from the Judge's lodgings, Carmarthen, as follows:—

It is impossible for me at the time now at my disposal to attempt an answer to your very interesting letter. Indeed, if I had abundance of time, my reading has been so desultory and superficial, and since I left the University its course has been so much guided by wayward and passing fancies, that I should be sorry to suggest to any one else the books which happen to have delighted me.

Generally speaking, I think Sir John Lubbock's list a very good one as far as I know the books which compose it. But I know nothing of Chinese and Sanscrit, and have no opinion whatever about the Chinese and Sanscrit works he refers to. To the classics I should add Catullus, Propertiues, Ovid (in selections), Pindar, and the pastoral writers, Theocritus, Bion, and Moschus

I should find a place among epic poets for Tasso, Ariosto, and I should suppose Camoens, though I know him only in translation. With the poem of Malory on the "Morte d'Arthur," I am quite unacquainted; Malory's prose romance under that title is familiar to many readers from Southey's reprint of (I think) Caxton's edition of it.

Among the Greek dramatists, I should give a more prominent place to Euripides—the friend of Socrates, the idol of Menander, the admiration of Milton and Charles Fox; and I should exclude Aristophanes, whose splendid genius does not seem to me to atone for the baseness and vulgarity of his mind. In history I shall exclude Hume as mere waste of time now to read, and include Tacitus and Livy and Lord Clarendon and Sismondi. I do not know enough about philosophy to offer any opinion.

In poetry and general literature, I should certainly include Dryden and some plays of Ben Jonson and Ford and Massinger and Shirley and Webster; Gray, Collins, Coleridge, Chatles Lamb, De Quincey, Bolingbroke, Sterne, and I should substitute Bryant for Longfellow, and most certainly I should add Cowper.

In fiction I should add Miss Austen, "Clarissa," "Tom Jones," "Humphrey Clinker;" and certainly exclude Kings!ey. But I am well away from all books and with no time for reflection, and, though courtesy leads me to reply to a very courteous letter, I have no wish that a hasty and imperfect note such as this should be taken as representing a deliberate opinion.

HIS EXCELLENCY THE AMERICAN MINISTER.

Sir,—I cannot decline to reply to your courteous note touching "The Best Hundred Books," though it is a subject upon which I am by no means an authority, being only a casual wanderer in the field of letters. It seems to me not easy to lay out a course of reading that shall be of universal application. So much depends upon the cast of the reader's mind, his taste (if he has any), and the line of study he wishes to follow, that "the best laid scheme" may still "gang aft a-gley."

Sir John Lubbock's list already published is excellent, and perhaps cannot be improved. It is difficult to take from it, and, in trying to add, one encounters the embarrassment of riches. Taking that as a foundation were I to put my own inclination in the place of his better judgment, I should venture to increase it in general literature by the essays of Bacon, Johnson, Sterne, John Wilson, Carlyle, and Washington Irving, and the greater speeches of Webster. In poetry, by Chaucer, Dryden, Goldsmith, Gray, Coleridge, Burns, Byron, and Bryant. In fiction, by Cervantes and Le Sage, and all of Thackeray and Dickens that Sir John omits. In history, by Clarendon, Hallam, Macaulay, and the Americans Motley and Prescott. In political science, by Montesquieu's "Spirit of Laws," Guizot's "Civilization," and De Tocqueville's "Democracy." In the fine arts, by Lübke's "History of Art," Kugler's "Italian, Flemish, and Spanish Painters," Taylor's "Fine Art in Great Britain," and Fergusson's "History of Architecture."

If these additions carry the list beyond the limit, rather than lose my favourites, I would make room for them by cutting down somewhat the selections from translations of classical and Oriental literature, and from philosophy and theology, though retaining always in the latter John Bunyan and Jeremy Taylor. I cannot think the finis et fructus of liberal reading is reached by him who has not obtained in the best writings of our English tongue the generous acquaintance that ripens into affection. If he must stint himself, let him save elsewhere.

Even thus augmented, our list still excludes the whole range of living authors, all scientific, technical, and professional knowledge, and many charming books in literature, and enters but sparingly into the broad and fertile field of history. When these gaps are filled, the catalogue outruns us; and we find that as a book on one subject cannot be compared with that on another, no possible "hundred" can be exclusively "the best."

But after all power of choice has been exhausted, it still remains to be remembered that what good comes of it at last depends more upon digestion than upon acquisition. The reader who does not keep up a sound digestion will be apt to find good books disagree with him, and will only help to illustrate what is already sufficiently proved, that it is much easier to make a pedant, a prig, or a blatherskite than it is to make a scholar.—I am. Sir. your obedient servant,

E. J. Phelps.

III.—Men and Women of Letters.

NONE of our lists will, we imagine, be read with greater interest than those drawn up by men of letters. Everybody reads their books, and everybody will be interested to know what books they in their turn read. We ought here to explain that many of the judges whose verdicts are recorded later on might equally well have been included under this head; but we thought it would be more instructive, as well as more convenient, to allow ourselves the liberty of cross division.

MR. RUSKIN.

Brantwood, Coniston, Jan. 13, 1886.

My dear Sir,—Putting my pen lightly through the needless—and blottesquely through the rubbish and poison of Sir John's list—I leave enough for life's liberal reading—and choice for any true worker's loyal reading. I should add one quite vital and essential book—Livy (the two first books), and three plays of Aristophanes (Clouds, Birds, and Plutus). Of travels I read myself all old ones I can get hold of; of modern, Humboldt is the central model. Forbes (James Forbes in Alps) is essential to the modern Swiss tourist—of sense.—Ever faithfully your,J. R.

The following is a facsimile of the list as "blottesquely" amended by Mr. Ruskin:—

Mr. Ruskin on the Choice of Books.

MR. RUSKIN subsequently sent us the following letter, which deals generally with the subject of the choice of the books, and also gives his reasons for some of the "blottesque" emendations in the foregoing list:—

Sir,—Several points have been left out of consideration both by you and by Sir John Lubbock, in your recent inquiries and advices concerning books. Especially Sir John, in his charming description of the pleasures of reading for the nineteenth century, leaves curiously out of mention its miseries; and among the various answers sent to the Pall MalL I find nobody laying down, to begin with, any one canon or test by which a good book is to be known from a bad one.

Neither does it seem to enter into the respondent minds to ask, in any case, whom, or what the book is to be good for—young people or old, sick or strong, innocent or worldly—to make the giddy sober, or the grave gay. Above all, they do not distinguish between books for the labourer and the schoolman; and the idea that any well-conducted mortal life could find leisure enough to read a hundred books would have kept me wholly silent on the matter, but that I was fain, when you sent me Sir John's list, to strike out, for my own pupils' sake, the books I would forbid them to be plagued with.

For, of all the plagues that afflict mortality, the venom of a bad book to weak people, and the charms of a foolish one to simple people, are without question the deadliest; and they are so far from being redeemed by the too imperfect work of the best writers, that I never would wish to see a child taught to read at all, unless the other conditions of its education were alike gentle and judicious.

And to put the matter into anything like tractable order at all, you must first separate the scholar from the public. A well-trained gentleman should, of course, know the literature of his own country, and half-a-dozen classics thoroughly, glancing at what else he likes; but, unless he wishes to travel or to receive strangers, there is no need for his troubling himself with the languages or literature of modern Europe. I know French pretty well myself. I never recollect the gender of anything, and don't know more than the present indicative of any verb; but with a dictionary I can read a novel,—and the result is my wasting a great deal of time over Scribe, Dumas, and Gaboriau, and becoming a weaker and more foolish person in all manner of ways therefore. French scientific books are, however, out and out the best in the world; and, of course, if a man is to be scientific, he should know both French and Italian. The best German books should at once be translated into French, for the world's sake, by the French Academy;—Mr. Lowell is altogether right in pointing out that nobody with respect for his eyesight can read them in the original.

I have no doubt there is a great deal of literature in the East, in which people who live in the East, or travel there, may be rightly interested. I have read three or four pages of the translation of the Koran, and never want to read any more; the Arabian Nights many times over, and much wish, now, I had been better employed.

As for advice to scholars in general, I do not see how any modest scholar could venture to advise another. Every man has his own field, and can only by his own sense discover what is good for him in it. I will venture, however, to protest, somewhat sharply, against Sir John's permission to read any book fast. To do anything fast—that is to say at a greater rate than hat at which it can be done well—is a folly: but of all follies reading fast is the least excusable. You miss the points of a book by doing so, and misunderstand the rest.

Leaving the scholar to his discretion, and turning to the public, they fall at first into the broad classes of workers and idlers. The whole body of modern circulating library literature is produced for the amusement of the families so daintily pictured in Punch—mama lying on a sofa showing her pretty feet—and the children delightfully teazing the governess, and nurse, and maid, and footman—the close of the day consisting of state-dinner and reception. And Sir John recommends this kind of people to read Homer, Dante, and Epictetus! Surely the most beneficent and innocent of all books yet produced for them is the Book of Nonsense, with its corollary carols?—inimitable and refreshing, and perfect in rhythm. I really don't know any author to whom I am half so grateful, for my idle self, as Edward Lear. I shall put him first of my hundred authors.

Then there used to be Andersen! but he has been minced up, and washed up, and squeezed up, and rolled out, till one knows him no more. Nobody names him, of the omnilegent judges: but a pure edition of him, gaily illustrated, would be a treasure anywhere—perhaps even to the workers, whom it is hard to please.

But I did not begin this talk to recommend anything, but to ask you to give me room to answer questions, of which I receive many by letter, why I effaced such and such books from Sir John's list.

1. Grote's History of Greece.—Because there is probably no commercial establishment, between Charing-cross and the Bank, whose head clerk could not write a better one, if he had the vanity to waste his time on it.

2. Confessions of St. Augustine.—Because religious people nearly always think too much about themselves; and there are many saints whom it is much more desirable to know the history of. St. Patrick to begin with—especially in present times.

3. John Stuart Mill—Sir John Lubbock ought to have known that his day was over.

4. Charles Kingslay.—Because his sentiment is false and his tragedy frightful. People who buy cheap clothes are not punished in real life by catching fevers; social inequalities are not to be redressed by tailors falling in love with bishops' daughters, or gamekeepers with squires'; and the story of "Hypatia" is the most ghastly in Christian tradition, and should for ever have been left in silence.

5. Darwin.—Because it is every man's duty to know what he is, and not to think of the embryo he was, nor the skeleton that he shall be. Because also, Darwin has a mortal fascination for all vainly curious and idly speculative persons, and has collected, in the train of him, every impudent imbecility in Europe, like a dim comet wagging its useless tail of phosphorescent nothing across the steadfast stars.

6. Gibbon—Primarily, none but the malignant and the weak study the Decline and Fall either of State or organism. Dissolution and putrescence are alike common and unclean in all things; any wretch or simpleton may observe for himself, and experience himself, the processes of ruin; but good men study and wise men describe, oaly the growth and standing of things,—not their decay.

For the rest, Gibbon's is the worst English that was ever written by an educated Englishman. Having no imagination and little logic, he is alike incapable either of picturesqueness or wit: his epithets are malicious without point, sonorous without weight, and have no office but to make a flat sentence turgid.

7. Voltaire—His work is, in comparison with good literature, what nitric acid is to wine, and sulphuretted hydrogen to air. Literary chemists cannot but take account of the sting and stench of him; but he has no place in the library of a thoughtful scholar. Every man of sense knows more of the world than Voltaire can tell him; and what he wishes to express of such knowledge he will say without a snarl.

I cannot here enter into another very grave and wide question which neither the Pall Mall nor its respondents ask, respecting literature for the young, but will merely point out one total want in the present confused supply of it—that of intelligible books on natural history. I chanced at breakfast the other day, to wish I knew something of the biography of a shrimp, the rather that I was under the impression of having seen jumping shrimps on a sandy shore express great satisfaction in their life.

My shelves are loaded with books on natural history, but I could find nothing about shrimps except that "they swim in the water, or lie upon the sand in shoals, and are taken in multitudes for the table."

John Ruskin.

MR. SWINBURNE.

Sir,—I must apologize for the inevitable discourtesy of delay in answering your letter. judging from what I have seen, that any man's or woman's opinion on the relative value of a hundred books of all kinds which he or she might select as the most precious to humanity in general could itself be of any value to any one not concerned in the diagnosis of that man's or woman's morbid development of intellectual presumption and moral audacity. I send you, therefore, simply the list of a student whose reading has lain mainly, though by no means exclusively, in the line of imaginative or creative literature.

There are names which I have not taken upon myself to insert, as assuredly I should not have taken upon myself to reject them, of whose claims to a foremost place I should be sorry to be thought ignorant. It would be superfluous, I presume, for any educated Englishman to say that he does not question the pre-eminence of such names as Bacon and Darwin; but the only possible value of any man's special opinion, it seems to me, must depend, with regard to such writers as these, on the knowledge to be gained only by especial, if not exclusive, study.

I need only add (and, indeed, perhaps I need not add) that after the first two or three entries this list does not give my estimate of the greatness of the names included by the perhaps inevitably chaotic or heterogeneous arrangement, which I have not leisure to remedy or reform.

I am not sure that you may think "selections" from various volumes of ballads or other lyric poetry (25, 27) accurately definable or classifiable as books having an individual vitality of their own. But, as I cannot help thinking some of these waifs and strays worthy to be ranked among the most precious treasures of our own or any language, I could not properly refrain from entering them on my register. In some cases my "selections" would be large, in others very small but very precious. You will see that I have included no living names, and will, therefore, not be surprised that those of Lord Tennyson and M. Leconte de Lisle—to mention none but these two pre-eminent contemporaries—should be wanting. Some entries in any list, I presume, must seem frivolous or eccentric or perverse to readers of different tastes, and many omissions in mine may probably be attributed to pure ignorance as much as to want of taste.—Yours very truly, A. C. Swinburne.

1. Shakspeare.

2. Æschylus.

3. Selections from the Bible: comprising Job, the Psalms, Ecclesiastes, the Song of Solomon, Isaiah, Ezekiel, Joel: the Gospels of St. Matthew and St. Luke, the Gospel and the First Epistle of St. John, and the Epistle of St. James.

4. Homer.

5. Sophocles.

6. Aristophanes.

7. Pindar.

8. Lucretius.

9. Catullus.

10. Dante.

11. Chaucer.

12. Villon.

13. Marlowe.

14. Webster.

15. Molière.

16. Rabelais.

17. Epictetus.

18. Mill on Liberty.

19. Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyám (Fitzgerald's 1st version, 1859).

20. Milton.

21. Shelley.

22. Victor Hugo

23. Landor

24. Boccaccio.

25. Ballads of North England and Scotland (from Percy, Scott, Motherwell, and other selections).

26. Sir Philip Sidney (Astrophel and Stella).

27. Selections from the lyric poetry of the are of Shakspeare (England's Helicon, &c.)

28. Charles Lamb.

29. Boswell's Life of Johnson.

Select Works (30–50):

30. Coleridge verse and prose.)

31. Scott (prose and verse.)

32. Blake.

33. Wordsworth.

34. Spenser.

35. Keats.

36. Mrs. Browning.

37. Burns.

38. Byron—"Don Juan." Cant. I.–VIII., XI.–XVI. inclusive, and "Vision of Judgment."

39. Balzac.

40. Dickens.

41. Thackeray.

42. Swift.

43. Ben Jonson.

44. Beaumont and Fletcher.

45. Ford.

46. Dekker.

47. Tourneur,

48. Marston.

49. Middleton.

50. Rossetti.

51. Theocritus.

52. Story of the Volsungs and the Niblungs.

53. The Saga of Burnt Njal.

54. Lockhart's Life of Scott.

55. Autobiography of Lord Herbert of Cherbury.

56. Malory's Morte d'Arthur.

57. Ariosto.

Select Works (58–100).

58. Donne.

59. Massinger.

60. Congreve.

61. Vanbrugh.

62. Dryden.

63. Pope.

64. Defoe.

65. Goldsmith,

66. Fielding.

67. Sterne.

68. Sheridan.

69. Butler (excerpts from ("Hudibras" and "Remains.")

70. Collins.

71. Grey.

72. Herrick.

73. Suckling . 74. Prior.

75. *Omitted by Mr. Swinburne.

76. Drayton.

77. George Herbert,

78. Crashaw.

79. Randolph.

80. Wither.

81. La Fontaine.

82. Voltaire.

83. Diderot.

84. Chamfort (Maxims).

85. Beaumarchais.

86. Stendhal.

87. Dumas.

88. Jane Austen.

89. Charlotte Brontë.

90. Emily Brontë (verse and prose).

91. Leigh Hunt.

92. Hood.

93. Mrs. Gaskell.

94. George Eliot.

95. Campbell.

96. Musset.

97. Macaulay.

98. Crabbe.

99. Meinhold (English translation).

100. Early English metrical romances, from the collections of Weber, Ritson and Wright.

* Mr. Swinburne subsequently supplied this omission in the following letter:—

Sir—As I find I have omitted one of my hundred, I am inclined to supply the gap with the name of Etherege, who, as I have just been reminded by a far wider and deeper student of English literature than myself, was the founder—among us—of the pure comedy of manners, as opposed to the Shakspearian comedy of fancy and the Jonsonian comedy of humour; and who was certainly a great master of style and dialogue.—Yours very truly,

A. C. Swinburne

MR. WILLIAM MORRIS.

Sir,—I answer your letter with much pleasure. Like my friend Mr. Swinburne, I do not pretend to prescribe reading for other people: the list I give you is of books which have profoundly impressed myself: I hope I shall be acquitted of egotism or conceit for having ventured to add a few notes to the list; in some cases I felt explanation was necessary; in all, it seemed to me that my opinion could be of no value unless it were given quite frankly; so I ask your readers to accept my list and notes as a confession such as might chance to fall from me in friendly conversation; and, after all, these are matters about which one must have an opinion, though it may, I feel too well, be sometimes prudent to conceal it.

My list seems a short one, but it includes a huge mass of reading. Also there is a kind of book which I think might be excluded in such lists, or at least put in a quite separate one. Such books are rather tools than books: one reads them for a definite purpose, for extracting information from them of some special kind. Among such books I should include works on philosophy, economics, and modern or critical history. I by no means intend to undervalue such books, but they are not, to my mind, works of art; their manner may be good, or even excellent, but it is not essential to them; their matter is a question of fact, not of taste. My list comprises only what I consider works of art.—I am, Sir, yours obediently,William Morris.

List.

| 1 | Hebrew Bible (excluding some twice done parts and some pieces of mere Jewish ecclesiasticism) | These books are of the kind which Mazzini called "Bibles;" they cannot always be measured by a literary standard, but to me are far more important than any literature. They are in no sense the work of individuals, but have grown up from the very hearts of the people.Some other books further down share in the nature of these "Bibles;" I have marked them with a star.* |

| 2 | Homer | |

| 3 | Hesiod | |

| 4 | The Edda (including some of the other early old Norse romantic genealogical poems) | |

| 5 | Beowulf | |

| 6 | Mahabharata | |

| 7 | Collections of folk tales, headed by Grimm and the Norse ones | |

| 8 | Irish and Welsh traditional poems | |

| *9 | Herodotus | Real ancient imaginative works. I have left out others of which (to confess and be hanged) I know littleor nothing. The greater part of the Latins I should call sham classics. I suppose that they have some good literary qualities; but I cannot help thinking that it is difficult to find out how much. I suspect superstition and authority have influenced them till it has become a mere matter of convention. Of course I admit the archæological value of some of them, especially Virgil and Ovid. |

| 10 | Plato | |

| 11 | Æschylus | |

| 12 | Sophocles | |

| 13 | Aristophanes | |

| 14 | Theocritus | |

| 15 | Lucretius | |

| 16 | Catullus | |

| 17 | Plutarch's Lives | |

| 18* | Heimskringla (the tales of the Norse Kings) | Uncritical or traditional history: almost all these books are admirable pieces of tale-telling: some of them rise into the dignity of prose epics, so to say, especially in parts. Note, for instance, the last battle of Olaf Tryggvason in Heimskringla; and the great rally of the rebels of Ghent in Froissart. |

| 19* | Some half-dozen of the best Icelandic Sagas | |

| 20 | The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle | |

| 21 | William of Malmsbury | |

| 22 | Froissart | |

| 23 | Anglo-Saxon lyrical pieces (like the Ruin and the Exile) | Mediæval poetry. I am sorry to say that I can only read even old German with great difficulty and labour; so I miss much good mediæval poetry—Hans Sachs, for instance. |

| 24 | Dante | |

| 25 | Chaucer | |

| 26 | Piers Plowman | |

| 27* | Nibelungennot | |

| 28* | The Danish and Scotch English Border ballads | |

| 29 | ||

| 30 | Omar Khayyám (though I don't know how much of the charm of this lovely poem is due to Fitzgerald, the translator) | |

| 31 | Other Arab and Persion poetry | |

| 32 | Renard the Fox | |

| 33 | A few of the best rhymed romances | |

| 34* | The Morte d'Arthur (Malory's). I know this is an ill digested collection of fragments, but some of the best of the books it is made from (Lancelot is the best of them) are so long and so cumbered with unnecessary matter that one is thankful to Mallory after all.) | Mediæval story-books. |

| 35 | The Thousand and One Nights. | |

| 36 | Boccaccio's Decameron. | |

| 37 | The Mabinogion. | |

| 38 | Shakespeare | Modern poets. I omit those of this generation whether dead or alive. Goethe and Heine I cannot read, since I don't know German and they cannot be translated. I hope I shall escape Boycotting at the hands of my countrymen for leaving out Milton; but the union in his works of cold classicalism with Puritanism (the two things which I hate most in the world) repels me so that I cannot read him. |

| 39 | Blake (the part of him which a mortal can understand) | |

| 40 | Coleridge | |

| 41 | Shelley | |

| 42 | Keats | |

| 43 | Byron | |

| 44 | Bunyan's Pilgrim Progress | Modern fiction. I should like to say here that I yield to no one, not even Ruskin, in my love and admiration for Scott; also that to my mind of the novelists of our generation Dickens is immeasurably ahead, |

| 45 | Defoe: Crusoe, Moll Flanders, Colonel Jack, Captain Singleton, Voyage round the World | |

| 46 | Scott's novels (except the one or two which he wrote when he was hardly alive) | |

| 47 | Dumas the elder (his good novels) | |

| 48 | Victor Hugo (his novels) | |

| 49 | Dickens | |

| 50 | George Borrow (Lavengro and Romany Rye) | |

| 51 | Sir Thomas More's Utopia | I don't know how to class these works. |

| 52 | Ruskin's Works (especially the ethical and politico-economical parts of them | |

| 53 | Thomas Carlyle's Works | |

| 54 | Grimm's Teutonic Mythology |

Though this last book is of the nature of the "tools" above-mentioned, it is so crammed with the material for imagination, and has in itself such a flavour of imagination, that I feel bound to put it down.

I should note that I have by no means intended to put down these books in their order of merit or importance, even in their own divisions.

Our circle of literary authorities would not have been complete without the opinion of some eminent woman of letters. Here, then, is the answer we received from one of the most learned and accomplished women of the time:—

LADY DILKE (MRS. MARK PATTISON).

Sir,—You ask me to send you a list of books on the lines indicated by Sir John Lubbock in his recent lecture at the Working Men's College, but allow me to say that in printing make some very excellent criticisms on the wisdom of "placing before working men, or any men whatever, such a vast and heterogeneous course of study," and with these criticisms I entirely agree. To be in a position to properly understand and appreciate the works on Sir John's list, I undertake to say that one must have spent at least thirty years in preparatory study, and have had the command of, say, something more than a thousand other volumes. And I would ask, further, is this list to be considered simply as a list of literary masterpieces, or is it to present us with a general scheme of knowledge? Any list of books constructed with a view to the realization of such an ideal as the latter would be a very complicated affair, to be rewritten, too, with each succeeding year. If, on the other hand, we are only citing masterpieces of literature and making fancy libraries which may illustrate the extent and catholicity of our own tastes, our task is easier, and on the rough lines laid down by my friend Sir John Lubbock, we may put together a very pretty one.

In order to spare your space, I will not, however, proceed to recapitulate the great names, such as Homer, Dante, Vergil, Shakspeare, &c., which are down on Sir John's list, and about which there can be no question; I will only mention a few books which seem to me (taking European letters only into consideration) to cry for notice, and which might profitably replace the works of Southey, Longfellow, Emerson, Bulwer Lytton, and others of minor note to whom Sir John has given equal place. I would add Epictetus and Boethius to the non-Christian moralists, and St. François de Sales's "Traité de l'Amour de Dieu" to the books on devotion; to the Classics, Pliny's Letters; under history I would mention De Commines' "Memoirs," Clarendon's "Rebellion," Schiller's "Thirty Years' War;" Hobbes's "Leviathan" should not be forgotten in Philosophy, and, making a subdivision for Political Philosophy, I would cite Machiavel's "Prince," Bodin's "Republic," Hooker's "Ecclesiastical Polity," Montesquieu's "Considérations sur la Grandeur et la Décadence des Romains," Bolingbroke, and Mdme. de Staël's "L'Allemagne." The famous "Familiar Colloquies" of Erasmus should surely find a place under Literature, nor should Tasso, Petrarch, Leopardi, Boccaccio, be forgotten. Racine, Mdme. de Sevigné, Le Sage ("Gil Blas"), La Bruyère, and La Rochefoucauld, Rousseau ("Confessions"), and Mrs. Craven's "Le Récit d'une Sœur," are as typical illustrations of the French genius as Molière. No readers of German can omit to make acquaintance with some of Schiller's plays and with Lessing's "Laokoon;" while among the English poets I would claim notice for Chaucer, for Dryden ("The Hind and Panther"), for Gray ("Elegy" and Sonnet), and for Collins ("Ode to the Passions"). Walton's Lives must not be forgotten, nor Johnson's "Lives of the Poets," and among the essayists surely Bacon, De Quincey, and Charles Lamb must have a place. Ruskin's "Crown of Wild Olive" and "Sesame and Lilies," Pater's "Marius the Epicurean," may also be added under this head, and no list of modern fiction which omits Spielhagen ("Problematische Naturen "), Hugo ("Notre Dame de Paris," "Les Travailleurs de la Mer"), and Balzac ("La Recherche de l'Absolu," "Eugénie Grandet," and "Peau de Chagrin") can be reckoned complete.—I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

Emilia F. S. Dilke.

IV.—Novelists, Actors, Playwrights.

WE give the authorities who fall under this head in alphabetical order:—

MISS BRADDON.

Dear Sir,—In reply to your letter of the 13th inst., I beg to say that my reading has been for the most part so desultory, and so much less in amount than I could have wished, that I feel myself in no way qualified to advise others what they should read or avoid reading.

I can, however, tell you the authors whose books have given me most pleasure:—

In Fiction—Dickens, Bulwer, Scott, Thackeray, Jane Austen, Charles Reade, George Eliot, and Wilkie Collins; Balzac and Daudet; Von Hillern, Marlitt, and Auerbach.

In Poetry—Chaucer, Shakspeare, Milton, Pope, Byron, Shelley, Keats, Tennyson, and Browning; Victor Hugo and Alfred de Musset; Heine. All other poets in a lesser degree and at a distance from these.

In General Literature—Bacon's Essays, Milton's Prose Works, Jeremy Taylor, Addison, Steele, De Quincey, Jeffrey, Macaulay's Essays, Southey's Commonplace Book, Buckle's Miscellanies, Carlyle's Miscellanies; Voltaire, Taine, Sainte-Beuve, Janin, Renan, Augier, Sardou, Molière.

In History—Gibbon, Hume, Macaulay, Carlyle, Lord Mahon, Froude, and Grote; Michelet, Sismondi, Lamartine, Voltaire.

In Metaphysics—Professor Jowett's Plato, Victor Cousin. Of Goethe's "Faust" I have been a devoted student, but could not struggle through "Wilhelm Meister."

Perhaps one quarter of the time I have been able to give to reading in the course of a very busy life has been spent upon the Quarterly and Edinburgh Reviews.—I am, dear Sir, faithfully yours,

M. E. Braddon,

MR. BURNAND.

My dear Sir,—How can I suggest any better reading than Happy Thoughts," "About Buying a Horse, "The Modern Sandford and Merton," "Strapmore," "One and Three," and "More Happy Thoughts "?—Yours truly,

F. C. Burnand.

P.S.—I should recommend "The Grammar of Assent," and all Cardinal Newman's works. His lectures on "Catholicism in England " are masterpieces.

MR. WILKIE COLLINS.

Sir,—You have proposed that I should recommend to inexperienced readers some of the books which are necessary for a liberal education; and you have kindly sent a list of works drawn out by Sir John Lubbock with this object in view, and recently published in your journal.

I am sincerely sensible of the compliment to myself which is implied in your suggestion; but I am at the same time afraid that you have addressed yourself to the wrong man. Let me own the truth. I add one more to the number of reckless people who astonish Sir John Lubbock by devoting little care to the selection of what they read. I pick up the literature that happens to fall in my way, and live upon it as well as I can—like the sparrows who are picking up the crumbs outside my window while I write. If I may still quote my experience of myself, let me add that I have never got any good out of a book unless the book interested me in the first instance. When I find that reading becomes an effort instead of a pleasure, I shut up the volume, respecting the eminent author, and admiring my enviable fellow-creatures who have succeeded where I have failed. These sentiments have been especially lively in me (to give an example) when I have laid aside in despair "Clarissa Harlowe," "La Nouvelle Héloise," the plays of Ben Jonson, Burke on "The Sublime and Beautiful," Hallam's "Middle Ages," and Roscoe's " Life of Leo the Tenth.". Is a person with this good reason to blush for himself (if he was only young enough to do it) the right sort of person to produce a list of books for readers in search of a liberal education? You will agree with me that he is capable of seriously recommending Sterne's "Sentimental Journey," as the best book of travels that has ever been written, and Byron's "Childe Harold" as the grandest poem which the world has seen since the first publication of "Paradise Lost."

After this confession, if I nevertheless venture to offer a few suggestions, will you trust my honesty, even while you doubt my discretion? In any case, the tomb of literature is close by you. You can give me decent burial in the waste-paper basket.

To begin with, What is a liberal education? If I stood at my house door, and put that question to the first ten intelligent-looking persons who passed by, I believe I should receive ten answers all at variance one with the other. My own ideas cordially recognize any system of education the direct tendency of which is to make us better Christians. Looking over Sir John Lubbock's list from this point of view—that is to say, assuming that the production of a good citizen represents the most valuable result of a liberal education—I submit that the best book which your correspondent has recommended is "The Vicar of Wakefield"—and of the many excellent schoolmasters (judging them by their works) in whose capacity for useful teaching he believes, the two in whom I, for my part, most implicitly trust are Walter Scott and Charles Dickens. Holding these extraordinary opinions, if you asked me to pick out a biographical work for general reading, I should choose (after Boswell's supremely great book, of course), Lockhart's "Life of Scott." Let the general reader follow my advice, and he will find himself not only introduced to the greatest genius that has ever written novels, but provided with the example of a man modest, just, generous, resolute, and merciful; a man whose very faults and failings have been transformed into virtues through the noble atonement that he offered, at the peril and the sacrifice of his life.

Let me not forget that the question of literary value must also be considered in recommending books, for this good reason, that positive literary value means positive literary attraction to the general reader. In this connection I have in my mind the most perfect letters in the English language when I introduce the enviable persons who have not yet read it to Moore's "Life of Byron." Again, if any voices crying in the literary wilderness ask me what travels it may be well to read, I do justice to the charm of an admirable style, presenting the results of true and vivid observation, when I mention the names of Beckford and Kinglake. Get Beckford's "Italy, Spain, and Portugal;" and, beginning towards the end of the book, whet your appetite by reading the "Excursion to the Monasteries of Alcobaça and Batalha," In Kinglake's case, "Eothen" is the title, and the cheap edition of the book is within everybody's reach. Kane (in "Arctic Explorations") and Mr. George Melville (in "The Lena Delta") are neither of them consummate masters of the English language; but they possess the rate and admirable gift of being able to make other people see what they have seen themselves. When you meet with travellers who are unable to do this, you will get nothing out of them but weariness of spirit. Shut up their books.

Keeping clear of living writers, may I recommend one or two works of fiction, on the chance that they may not have been mentioned, with a word of useful comment perhaps, in other lists?

Read, my good public, Mrs. Inchbald's "Simple Story," in which you will find the character of a young woman who is made interesting even by her faults—a rare triumph, I can tell you, in our art. Read Marryat's "Peter Simple" and "Midshipman Easy," and enjoy true humour and masterly knowledge of human nature. Let my dear lost friend, Charles Reade, seize on your interest, and never allow it to drop from beginning to end in "Hard Cash." Let Dumas keep you up all night over "Monte Cristo," and Balzac draw tears that honour him and honour you in "Père Goriot." Last, not least, do justice to a greater writer, shamefully neglected at the present time in England and America alike, who invented the sea story, and created the immortal character of "Leather Stocking." Read "The Pilot " and "Jack Tier;" read "The Deerslayer" and "The Pathfinder," and I believe you will be almost as grateful to Fenimore Cooper as I am.

It is time to have done. If I attempted to enumerate all the books that I might honestly recommend, I should employ as many secretaries as Napoleon the Great, and I should find nobody bold enough to read me to the end. As it is, some critical persons may object that there runs all through this letter the prejudice that might have been anticipated in a writer of what heavy people call "light literature." No, Sir. My prejudice is in favour of the only useful books that I know of—books in all departments of literature which invite the general reader, as distinguished from books that repel him. If it is answered that profitable reading is a matter of duty first and a matter of pleasure afterwards, let me shelter myself under the authority of Doctor Johnson. Never mind what I say—hear him (Boswell, vol. ii., page 213, ed. 1859):—"I would not advise a rigid adherence to a particular plan of study. I myself have never persisted in any plan for two days together. A man ought to read just as inclination leads him; for what he reads as a task will do him little good."

I first read those admirable words (in an earlier edition of Boswell) when I was a boy at school. What a consolation they were to me when I could not learn my lesson! What consolation they may still offer to bigger boys, in the same predicament, among books recommended to them by the highest authorities!—Believe me. Sir. faithfully yours,Wilkie Collins

MR. HENRY IRVING.

My dear Sir,—In reply to your courteous request I should say—Before a hundred books commend me first to the study of two—the Bible and Shakspeare.—Obediently yours,

Henry Irving

MRS. LYNN LINTON.

My dear Sir,—I should add to your list:—

"Pilgrim's Progress."

Green's "History of the English People."

Herbert Spencer (every word).

Lecky—and all Darwin.

Carlyle's full works (no selection) and George Eliot's.

Miss Austen.

Bates's and Wallace's and Livingstone's Travels.

Laing's "Travels in Norway."

Kinglake's "Eothen " and History of the Crimean War."

and to French literature Dumas (the elder), G. Sand, and Balzac, if the reader be a man. But, indeedm the wealth of what ought to be read by any one claiming to understand the best authors is almost unbounded. I have not answered you very satisfactorily. At this moment I am in a very network of occupation, and I am like a creature half strangled for want of time rather than of breath.—I am, faithfully yours,

E. Lynn Linton

MR. JAMES PAYN.

Dear Sir,—I have a great respect for Sir John Lubbock, but I do not agree with him as to systematic reading. When a particular object has to be attained reading cannot be too special; there is an enormous waste of intelligence through a neglect of this fact; but otherwise reading should "come by nature." When I look through the list of books you send me I cannot help saying to myself, "Here are the most admirable and varied materials for the formation of a prig." There is no more common mistake in these days than the education of people beyond their wits.—Yours truly,

James Payn.

V.—The Advice of the Churches.

SEVERAL correspondents in the course of the publication of these letters wrote to remonstrate with us for not yet having included among our judges any professedly spiritual advisers. "Many of us," said one of these correspondents, "would rather not fill up the theological corners of our libraries from Sir John Lubbock's selection, and it would be interesting to know the opinion of the Archbishops and Bishops, and what they read." So it would; but bishops are busy men, and have almost as little time to read, we expect, as journalists. With archdeacons it is happily different, and we give an interesting letter from a dignitary of the Church of England, who is equally popular as an author and as a preacher.

CARDINAL NEWMAN.

Cardinal Newman is sensible of the compliment paid him by the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette in asking of him a list of classical English authors, but is obliged to decline it, as feeling that he is not equal to the task.

ARCHDEACON FARRAR.

Feb. 10, 1886

Sir,—In obedience to your request I drew up a list of "the Best Hundred Books" some time ago. not think it worth while to send it, because it does not differ essentially from several of those which you have already printed.

Nearly all your correspondents mention the names of authors rather than of books; but the lists would have been more interesting if you had rigidly confined us to the choice of single treatises.

By "the Best Hundred Books" I suppose that you mean those which are of the most permanent and intrinsic worth to us at the present time, not those which we happen to like best or to read most frequently. Many of the best books ever written have perished of their own success. They have rendered themselves unnecessary by becoming a part of the universal heritage of thought and knowledge. Such books, for instance, as Copernicus's "De Revolutionibus Calestium Orbium" in science, or Luther's "Commentary on the Galatians" in theology, or Kant's "Kritik der reinen Vernunft" in philosophy, are types of books which have created an epoch, but which your correspondents do not mention because (I suppose) they have so completely achieved the work for which they were intended. The paradoxes of yesterday become the commonplaces of to-morrow.

There are five great sources of human knowledge—nature, conscience, history, experience—and all those inspired utterances of genius and intuition, whether Jewish or Ethnic, which make us see the things that are and see them as they are. by "the Best Hundred Books" those which are most necessary for a complete culture, it would be necessary to include various histories, biographies, and books of science which are relatively indispensable because they record the facts, or explain the phenomena, which are essential to our highest education.

But if all the books of the world were in a blaze the first twelve which I should snatch out of the flames would be the Bible, the "Imitatio Christi," Homer, Æschylus, Thucydides, Tacitus, Virgil, Marcus Aurelius, Dante, Shakspeare, Milton, Wordsworth.

Of living writers I would save first the works of Tennyson, Browning, and Ruskin.—Yours obediently,

Federic W. Farrar

To the letter of this representative Churchman we are glad to be able to add the advice of two equally representative Nonconformists:—

THE PRESIDENT OF THE CONGREGATIONAL UNION.

Sir,—Sir John Lubbock's catalogue of books will meet the reauirements of men of education and leisure, For persons of less complete education and leisure a humbler and shorter list may be acceptable. I subjoin my own choice for such as can obtain access to them, setting them down as they occur, without classification:—Green's "History of England," Professor Bryce's "History of the Holy Roman Empire," Emerson's twelve essays on "Society and Solitude," Helps's "Friends in Council," "Companions of My Solitude," and "Organization of Common Life," Boswell's "Johnson," Marcus Aurelius's translation of Plato's "Laws," Cowper's translation of Homer's "Odyssey," Mozley on "Miracles," Longfellow's "Dante," Plutarch's "Lives," Milton's prose works, Evelyn's "Diary," Pepys's Diary," Michelet's "History of France," Merovingian Era," Thierry's " Norman Conquest," Robertson's and Prescott's "Mexico" and "Peru," Strickland's "Queens of England," "Memoirs of Colonel Hutchinson," Charles Lamb's "Elia," Montaigne's "Essays," St. Simon's " Memoirs of the Reign of of Louis XIV.," Molière's plays, Bossuet's "Funeral Orations," Shakspeare's plays, and specially his sonnets, R. Burns's poems, Coleridge's poems, Matthew Arnold's poems, Mrs. Browning's poems, Crabbe's poems, Bishop Hall's "Meditations," William Tyndale's works, Sir W. Dawson's "Chain of Life " and "Fossil Men," Sydney Smith's essays, E. Thring's "Theory and Practice of Teaching," Whately's "Cautions for the Times," Newman's "Parochial Sermons," MacCulloch's "Illustrations of the Attributes of God from Physical Nature," Burnet's "History of his own Times," Whewell's "Foundations of Morals," Sir Walter Scott's Life (3), Wraxall's "Memoirs," L. Morris's "Epic of Hades," Thackeray's "Roundabout Papers," Basil Hail's "Voyages and Travels," Bacon's Essays, Huc's "Travels in Tartary," Pascal's "Provincial Letters," Sir W. Muir's "Life of Mohammed," "The Spectator," John Forster's (Foster) "Essays" and his Biography by Ryland, Meyrick on "The Necessity of Dogma," Henry Rogers on "Eclipse of Faith," F. D. Maurice's "Moral and Metaphysical Philosophy," Goldwin Smith on Rational Religion. Add to these an occasional course of reading in the Church Times, the Guardian, the Record, the Rock, the Watchman[1], the Nonconformist, the Inguirer, and the Freethinker, in order to see how diligently our contemporaries endeavour not to understand but to misrepresent each other; and by the aid of the books above mentioned I think the unlearned reader will find enough to instruct, amuse, and astonish him both in England and elsewhere.—I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

Edward White.

THE PRESIDENT OF THE BAPTIST UNION.

Dear Sir,—You have addressed me as the President of the Baptist Union. I am not sure, however, that I should carry all or the greater number of my brother Baptists with me in any specification I might make. In such matters there is liberty of opinion among us, and considerable divergence.

Allow me to point out that in the list as now published in the Contemporary Review by Sir John Lubbock there are many differences from that to which you have given currency. Three differences are almost all in the direction of your correspondents' criticisms. Thus the Bible now heads the list, and, in fact, there seems little to improve, on the whole, save by way of addition. Several of the Eastern books mentioned would be of true service to but few, We are all more or less conscientiously disposed to rate those books most highly which have most deeply influenced ourselves. We happened to read them at a specially susceptible period of our lives, and they are more to us than other books, not only through what they are in themselves, but through what they have suggested. For myself, I would say that three books not in the lists have, on the whole, done more for me than almost any others, excepting the few great masterpieces that have become a part of the intellectual life of every thoughtful man. These three are—(1) John Foster's Essays (surely not John Forster's, as printed in my friend Mr. Edward White's letter, a very different man); (2) Jonathan Edwards's "On the Freedom of the Will;" and (3) Stanley's "Life of Dr. Arnold." At a later period I find more in Maurice's Moral and Metaphysical Philosopliy " than in any metaphysical work I had read—certainly more than in that of Lewes's, which Sir John Lubbock mentions. On a general review of the list, I may venture to remark:—

1. In theology, I would omit Wake's "Apostolic Fathers," and add Augustine's "City of God;" also Butler's "Sermons on Human Nature" to his "Analogy." As an "epoch-making book" I would also mention Anselm's "Cur Deus Homo." The theological part of the list is in truth very scanty, nor have I much to add to it, save that in my judgment Baxter's "Saints' Rest" (in an unabridged, unaltered form) is worthy to be placed beside Jeremy Taylor's "Holy Living and Holy Dying;" and Charnock's posthumous discourses on "The Existence and Attributes of God" have always seemed to me the very flower of Puritan divinity.

2. In the Classical list there is little to add. There should be more of Plato—say the "Protagoras" and "Phædrus," with, of course, the "Apology of Socrates" as a supplement to the "Phædo." To the "De Corona" of Demosthenes I would add other orations, notably that "Against Leptines." Also the "Agamemnon" of Æschylus might be taken without its two companions, so making room for the whole "Œdipus" trilogy of Sophocles. To the "Medea" of Euripides why not add the "Alkestis" and the "Hecuba"? Aristophanes we should at least have the "Clouds," if not the "Birds" and Frogs."

The Latin list is scanty, and I would add to it considerably more of Tacitus—at least the Agricola and Annals I.—even if some of Livy had to be taken off. I see that Sir J. Lubbock gives all Horace and no Juvenal. I may be peculiar, but I would willingly exchange all the Satires and Epodes of the former for three or four of the Satires of the latter. The realism (to use the modern phrase) of Juvenal is less offensive than the corruptness of Horace.