Oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element. It has the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is the third most common element in the universe, after hydrogen and helium.

Liquid oxygen boiling | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxygen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allotropes | O2, O3 (ozone) and more (see Allotropes of oxygen) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | (O2) gas: colourless liquid and solid: pale blue | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(O) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [15.99903, 15.99977][1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Abundance | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| in the Earth's crust | 46% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| in the oceans | 86% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| in the solar system | 1% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxygen in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 16 (chalcogens) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [He] 2s2 2p4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | gas (O2) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 54.36 K (−218.79 °C, −361.82 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 90.188 K (−182.962 °C, −297.332 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (at STP) | 1.429 g/L | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at b.p.) | 1.141 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Triple point | 54.361 K, 0.1463 kPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 154.581 K, 5.043 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | (O2) 0.444 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | (O2) 6.82 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | (O2) 29.378 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 3.44 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 66±2 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 152 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | cubic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound | 330 m/s (gas, at 27 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 26.58×10−3 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | +3449.0·10−6 cm3/mol (293 K)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7782-44-7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1771) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Named by | Antoine Lavoisier (1777) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of oxygen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Oxygen is more than a fifth of the Earth's atmosphere by volume. In the air, two oxygen atoms usually join to make dioxygen (O

2), a colourless gas. This gas is often just called oxygen. It has no taste or smell. It is pale blue when it is liquid or solid.

Oxygen is part of the chalcogen group on the periodic table. It is a very reactive nonmetal. It makes oxides and other compounds with many elements. The oxygen in these oxides and in other compounds (mostly silicate minerals, and calcium carbonate in limestone) makes up nearly half of the Earth's crust, by mass.

Most living things use oxygen in respiration. Many molecules in living things have oxygen in them, such as proteins, nucleic acids, carbohydrates and fats. Oxygen is a part of water, which all known life needs to live. Algae, cyanobacteria and plants make the Earth's oxygen gas by photosynthesis. They use the Sun's light to get hydrogen from water, giving off oxygen.

At the top of the Earth's atmosphere is ozone (O

3), in the ozone layer. It absorbs ultraviolet radiation, which means less radiation reaches ground level.

Oxygen gas is used for making steel, plastics and textiles. It also has medical uses and is used for breathing when there is no good air (by divers and firefighters, for example), and for welding. Liquid oxygen and oxygen-rich compounds can be used as a rocket propellant.

History

Oxygen gas (O

2) was isolated by Michael Sendivogius before 1604. It is often thought that the gas was discovered in 1773 by Carl Wilhelm Scheele, in Sweden, or in 1774 by Joseph Priestley, in England. Priestley is usually thought to be the main discoverer because his work was published first (although he called it "dephlogisticated air", and did not think it was a chemical element). Antoine Lavoisier gave the name oxygène to the gas in 1777. He was the first person to say it was a chemical element. He was also right about how it helps combustion work.

Early experiments

One of the first known experiments on how combustion needs air was carried out by Greek Philo of Byzantium in the 2nd century BC. He wrote in his work Pneumatica that turning a vessel upside down over a burning candle and putting water around this vessel meant that some water went into the vessel.[3] Philo thought this was because the air was turned into the classical element fire. This is wrong. A long time after, Leonardo da Vinci worked out that some air was used up during combustion, and this forced water into the vessel.[4]

In the late 17th century, Robert Boyle found that air is needed for combustion. English chemist John Mayow added to this by showing that fire only needed a part of air. We now call this oxygen (O2).[5] He found that a candle burning in a closed container made the water rise to replace a fourteenth of the air's volume before it went out.[6] The same thing happened when a live mouse was put into the box. From this, he worked out that oxygen is used for both respiration and combustion.

Phlogiston theory

Robert Hooke, Ole Borch, Mikhail Lomonosov and Pierre Bayen all made oxygen in experiments in the 17th and 18th centuries. None of them thought it was a chemical element.[7] This was probably because of the idea of the phlogiston theory. This was what most people believed caused combustion and corrosion.[8]

J. J. Becher came up with the theory in 1667, and Georg Ernst Stahl added to it in 1731.[9] The phlogiston theory stated that all combustible materials were made of two parts. One part, called phlogiston, was given off when the substance containing it was burned.[4]

Materials that leave very little residue when they burn, like wood or coal, were thought to be made mostly of phlogiston. Things that corrode, like iron, were thought to contain very little. Air was not part of this theory.[4]

Discovery

Polish alchemist, philosopher and physician Michael Sendivogius wrote about something in air that he called the "food of life",[10] and this meant what we now call oxygen.[11] Sendivogius found, between 1598 and 1604, that the substance in air is the same as he got by heating potassium nitrate. Some people believe this was the discovery of oxygen while others disagree. Some say that oxygen was discovered by Swedish pharmacist Carl Wilhelm Scheele. He got oxygen in 1771 by heating mercuric oxide and some nitrates.[4][12][13] Scheele called the gas "fire air", because it was the only gas known to allow combustion (gases were called "airs" at this time). He published his discovery in 1777.[14]

On 1 August 1774, British clergyman Joseph Priestley focused sunlight on mercuric oxide in a glass tube. From this experiment he got a gas that he called "dephlogisticated air".[13] He found that candles burned more brightly in the gas and a mouse lived longer while breathing it. After breathing the gas, Priestley said that it felt like normal air, but his lungs felt lighter and easy afterwards.[7] His findings were published in 1775.[4][15] It is because his findings were published first that he is often said to have discovered oxygen.

French chemist Antoine Lavoisier later said he had discovered the substance as well. Priestley visited him in 1774 and told him about his experiment. Scheele also sent a letter to Lavoisier in that year that spoke of his discovery.[14]

Lavoisier's research

Lavoisier did the first main experiments on oxidation. He was the first person to explain how combustion works.[13] He used these and other experiments to prove the phlogiston theory wrong. He also tried to prove that the substance discovered by Priestley and Scheele was a chemical element.

In one experiment, Lavoisier found that there was no increase in weight when tin and air were heated in a closed container. He also found that air rushed in when the container was opened. After this, he found that the weight of the tin had increased by the same amount as the weight of the air that rushed in. He published his findings in 1777.[13] He wrote that air was made up of two gases. One he called "vital air" (oxygen), which is needed for combustion and respiration. The other (nitrogen) he called "azote", which means "lifeless" in Greek. (This is still the name of nitrogen in some languages, including French.)[13]

Lavoisier renamed "vital air" to "oxygène", from Greek words meaning "sour making" or "producer of acid". He called it this because he thought oxygen was in all acids, which is wrong.[16] Later chemists realised that Lavoiser's name for the gas was wrong, but the name was too common by then to change.[17]

"Oxygen" became the name in the English language, even though English scientists were against it.

Later history

John Dalton's theory of atoms said that all elements had one atom and atoms in compounds were usually alone. For example, he wrongly thought that water (H2O) had the formula of just HO.[18] In 1805, Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac and Alexander von Humboldt showed that water is made up of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom. By 1811, Amedeo Avogadro correctly worked out what water was made of based on Avogadro's law.[19]

By the late 19th century, scientists found that air could be turned into a liquid and the compounds in it could be isolated by compressing and cooling it. Swiss chemist and physicist Raoul Pictet discovered liquid oxygen by evaporating sulfur dioxide to turn carbon dioxide into a liquid. This was then also evaporated to cool oxygen gas in order to turn it into a liquid. He sent a telegram to the French Academy of Sciences on 22 December 1877 telling them of his discovery.[20]

Characteristics

Properties and molecular structure

At standard temperature and pressure, oxygen has no colour, odour or taste. It is a gas with the chemical formula O

2 called dioxygen.[21]

As dioxygen (or just oxygen gas), two oxygen atoms are chemically bound to each other. This bond can be called many things, but simply called a covalent double bond. Oxygen gas is very reactive and can react with many other elements. Oxides are made when metal elements react with oxygen, such as iron oxide, which is known as rust. There are a lot of oxide compounds on Earth.

Allotropes

The common allotrope (type) of oxygen on Earth is called dioxygen (O2). This is the second biggest part of the Earth's atmosphere, after dinitrogen (N2). O2 has a bond length of 121 pm and a bond energy of 498 kJ/mol[22] Because of its energy, O2 is used by complex life like animals.

Ozone (O3) is very reactive and damages the lungs when breathed in.[23] Ozone is made in the upper atmosphere when O2 combines with pure oxygen made when O2 is split by ultraviolet radiation.[16] Ozone absorbs a lot of radiation in the UV part of the electromagnetic spectrum and so the ozone layer in the upper atmosphere protects Earth from radiation.

Above the ozone layer, (in low Earth orbits), atomic oxygen becomes the most common form.[24]

Tetraoxygen (O4) was discovered in 2001.[25][26] It only exists in extreme conditions when a lot of pressure is put onto O2.

Physical properties

Oxygen dissolves more easily from air into water than nitrogen does. When there is the same amount of air and water, there is one molecule of O2 for every 2 molecules of N2 (a ratio of 1:2). This is different to air, where there is a 1:4 ratio of oxygen to nitrogen. It is also easier for O2 to dissolve in freshwater than in seawater.[7][27] Oxygen condenses at 90.20 K (-182.95°C, -297.31 °F) and freezes at 54.36 K (-218.79 °C, -361.82 °F).[28] Both liquid and solid O2 are see-through with a light-blue colour.

Oxygen is very reactive and must be kept away from anything that can burn.[29]

Isotopes

There are three stable isotopes of oxygen in nature. They are 16O, 17O, and 18O. About 99.7% of oxygen is the 16O isotope.[30]

Occurrence

Oxygen is the third most common element in the universe, after hydrogen and helium.[31] About 0.9% of the Sun's mass is oxygen.[13]

| Z | Element | Mass fraction in parts per million | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hydrogen | 739,000 | 71 × mass of oxygen (red bar) | |

| 2 | Helium | 240,000 | 23 × mass of oxygen (red bar) | |

| 8 | Oxygen | 10,400 | ||

| 6 | Carbon | 4,600 | ||

| 10 | Neon | 1,340 | ||

Apart from iron, oxygen is the most common element on Earth (by mass). It makes up nearly half (46%

to 49.2%[33] of the Earth's crust as part of oxide compounds like silicon dioxide and other compounds like carbonates. It is also the main part of the Earth's oceans, making up 88.8% by mass. Oxygen gas is the second most common part of the atmosphere, making up 20.95%[34] of its volume and 23.1% of its volume. Earth is strange compared to other planets, as a large amount of its atmosphere is oxygen gas. Mars has only 0.1% O

2 by volume, and the other planets have less than that.

The much higher amount of oxygen gas around Earth is caused by the oxygen cycle. Photosynthesis takes hydrogen from water using energy from sunlight. This gives off oxygen gas. Some of the hydrogen combines with carbon dioxide to make carbohydrates. Respiration then takes oxygen gas out of the atmosphere or water and turns it into carbon dioxide and water. [35]

Uses

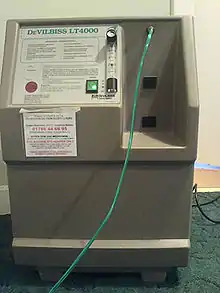

Medical

O2 is a very important part of respiration. Because of this, it is used in medicine. It is used to increase the amount of oxygen in a persons blood so more respiration can take place. This can make them become healthy quicker if they are ill. Oxygen therapy is used to treat emphysema, pneumonia, some heart problems, and any disease that makes it harder for a person to take in oxygen.[36]

Life support

Low-pressure O2 is used in space suits, surrounding the body with the gas. Pure oxygen is used but at a much lower pressure. If the pressure were higher, it would be poisonous.[37][38]

Industrial

Smelting of iron ore into steel uses about 55% of oxygen made by humans.[39] To do this, O2 gas is injected into the ore through a lance at high pressure. This removes any sulfur or carbon from the ore that would not be wanted. They are given off as sulfur oxide and carbon dioxide. The temperature can go as high as 1,700 °C because it is an exothermic reaction.[39]

Around 25% of oxygen made by humans is used by chemists.[39] Ethylene is reacted with O2 to make ethylene oxide. This is then changed to ethylene glycol, which is used to make many products such as antifreeze and polyester (these can then be turned into plastics and fabrics).[39]

The other 20% of oxygen made by humans is used in medicine, metal cutting and welding, rocket fuel, and water treatment.[39]

Compounds

The oxidation state of oxygen is −2 in nearly every compound it is in. In a few compounds, the oxidation state is −1, such as peroxides. Compounds of oxygen with other oxygen states are very uncommon.[40]

Oxides and other inorganic compounds

Water (H

2O) is an oxide of hydrogen. It is the most common oxide on Earth. All known life needs water to live. Water is made of two hydrogen atoms covalent bonded to an oxygen atom (oxygen has a higher electronegativity than hydrogen).[41] (this is the basic principle of covalent bonding)

There are also electrostatic forces (Van de'r Waals forces) between the hydrogen atoms and adjacent molecules' oxygen atoms. These pseudo-bonds bring the atoms around 15% closer to each other than most other simple liquids. This is because Water is a polar molecule (Net asymmetrical distribution of electrons) due to its bent shape, giving it an overall net field direction, mainly due to oxygens 2 non bonding pairs of electrons, pushing the bonding H's further together than the linear arrangement with lower enthalpy (see CO2). This property is exploited by microwaves to oscillate polar molecules, especially water. And its responsible for the extra energy needed to disassociate H20.[42]

Because of oxygen's high electronegativity, it makes chemical bonds with almost all other chemical elements. These bonds give oxides (for example iron reacts with oxygen to give iron oxide). Most metal's surfaces are turned into oxides when in air. Iron's surface will turn to rust (iron oxide) when in air for a long time. There are small amounts of carbon dioxide (CO

2) in the air, and it is turned into carbohydrates during photosynthesis. Living things give it off during respiration.[43]

Organic compounds

Many organic compounds have oxygen in them. Some of the classes of organic compounds that have oxygen are alcohols, ethers, ketones, aldehydes, carboxylic acids, esters, and amides. Many organic solvents also have oxygen, such as acetone, methanol, and isopropanol. Oxygen is also found in nearly all biomolecules that are made by living things.

Oxygen also reacts quickly with many organic compounds at, or below, room temperature when autoxidation happens.[44]

Industrial production

One hundred million tonnes of O2 are gotten from air for industrial uses every year. Industries use two main methods to make oxygen. The most common method is fractional distillation of liquefied air. N2 evaporates while O2 is left as a liquid.[7] O2 is the second most important industrial gas.Because it is more economical , oxygen is usually stored and transported as a liquid. A small steel tank of 16 liters water capacity with a working pressure of 139 bar (2015 psi) holds about 2150 liters of gas and weighs 28 kilograms (62 lb) empty. 2150 liters of oxygen weighs about 3 kilograms (6.6 lb).

The other main method of making oxygen is by passing a stream of clean, dry air through a pair of zeolite molecular sieves. The zeolite molecular sieves soaks up the nitrogen. It gives a stream of gas that is 90% to 93% oxygen.[7]

Oxygen gas can also be made through electrolysis of water into molecular oxygen and hydrogen.[7]

Safety

Oxygen's NFPA 704 says that compressed oxygen gas is not dangerous to health and is not flammable.[45]

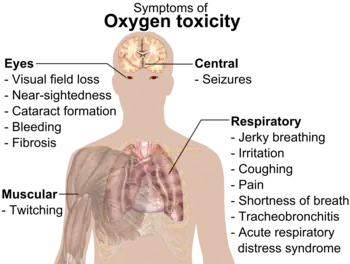

Toxicity

At high pressures, oxygen gas (O2) can be dangerous to animals, including humans. It can cause convulsions and other health problems.[lower-alpha 1][46] Oxygen toxicity usually begins to occur at pressures more than 50 kilopascals (kPa), equal to about 50% oxygen in the air at standard pressure (air on Earth has around 20% oxygen).[7]

Premature babies used to be placed in boxes with air with a high amount of O2. This was stopped when some babies went blind from the oxygen.[7]

Breathing pure O2 in space suits causes no damage because there is a lower pressure used.[47]

Combustion and other hazards

Concentrated amounts of pure O2 can cause a quick fire. When concentrated oxygen and fuels are brought close together, a slight ignition can cause a huge fire.[48] The Apollo 1 crew were all killed by a fire because the air of the capsule had a very high amount of oxygen.[lower-alpha 2][50]

If liquid oxygen is spilled onto organic compounds, like wood, it can explode.[48]

Related pages

References

- "Standard Atomic Weights: Oxygen". CIAAW. 2009.

- Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- Jastrow, Joseph (1936). Story of Human Error. Ayer Publishing. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-8369-0568-7.

- Cook, Gerhard A. & Lauer, Carol M. 1968. "Oxygen". In Clifford A. Hampel (ed.). The Encyclopedia of the Chemical Elements. New York: Reinhold Book Corporation. pp. 499–512. LCCN 68-29938. p499.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 938–939.

- "John Mayow". World of Chemistry. Thomson Gale. 2005. ISBN 978-0-669-32727-4. Retrieved December 16, 2007.

- Emsley 2001, p.299

- Best, Nicholas W. (2015). "Lavoisier's 'Reflections on Phlogiston' I: Against Phlogiston Theory". Foundations of Chemistry. 17 (2): 137–151. doi:10.1007/s10698-015-9220-5. S2CID 170422925.

- Morris, Richard (2003). The last sorcerers: The path from alchemy to the periodic table. Washington, D.C.: Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 978-0-309-08905-0.

- Marples, Frater James A. "Michael Sendivogius, Rosicrucian, and father of studies of oxygen" (PDF). Societas Rosicruciana in Civitatibus Foederatis, Nebraska College. pp. 3–4. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- Bugaj, Roman (1971). "Michał Sędziwój - Traktat o Kamieniu Filozoficznym". Biblioteka Problemów (in Polish). 164: 83–84. ISSN 0137-5032.

- "Oxygen". RSC.org. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- Cook & Lauer 1968, p. 500

- Emsley 2001, p. 300

- Priestley, Joseph (1775). "An account of further discoveries in air". Philosophical Transactions. 65: 384–94. doi:10.1098/rstl.1775.0039. S2CID 186214794.

- Parks, G. D.; Mellor, J. W. (1939). Mellor's Modern Inorganic Chemistry (6th ed.). London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Greenwood & Earnshaw, pg. 793

- DeTurck, Dennis; Gladney, Larry; Pietrovito, Anthony (1997). "Do We Take Atoms for Granted?". The Interactive Textbook of PFP96. University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved January 28, 2008.

- Roscoe, Henry Enfield; Schorlemmer, Carl (1883). A Treatise on Chemistry. D. Appleton and Co. p. 38.

- Daintith, John (1994). Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists. CRC Press. p. 707. ISBN 978-0-7503-0287-6.

- "Oxygen Facts". Science Kids. February 6, 2015. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- Chieh, Chung. "Bond Lengths and Energies". University of Waterloo. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007. Retrieved December 16, 2007.

- Stwertka, Albert (1998). Guide to the Elements (Revised ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-19-508083-4.

- "Atomic oxygen erosion". Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

atomic oxygen, the major component of the low Earth orbit environment

- Cacace, Fulvio; de Petris, Giulia; Troiani, Anna (2001). "Experimental Detection of Tetraoxygen". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 40 (21): 4062–65. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20011105)40:21<4062::AID-ANIE4062>3.0.CO;2-X. PMID 12404493.

- Ball, Phillip (September 16, 2001). "New form of oxygen found". Nature News. Retrieved January 9, 2008.

- "Air solubility in water". The Engineering Toolbox. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- Lide, David R. (2003). "Section 4, Properties of the elements and inorganic Compounds; melting, boiling, and critical temperatures of the elements". CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (84th ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-0595-5.

- "Liquid Oxygen Material Safety Data Sheet" (PDF). Matheson Tri Gas. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- "Oxygen Nuclides / Isotopes". EnvironmentalChemistry.com. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- Emsley 2001, p.297

- Croswell, Ken (February 1996). Alchemy of the Heavens. Anchor. ISBN 978-0-385-47214-2.

- "Oxygen". Los Alamos National Laboratory. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved December 16, 2007.

- Mackenzie, F.T. and J.A. (1995). "Gaseous Composition of Dry Air". Our changing planet. Prentice-Hall. pp. 288–307. Archived from the original on 2020-04-13. Retrieved 2020-07-02.

20.947

- Canfield, Donald 2014. Oxygen: a four billion year history. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14502-0

- Cook & Lauer 1968, p.510

- Morgenthaler GW; Fester DA; Cooley CG (1994). "As assessment of habitat pressure, oxygen fraction, and EVA suit design for space operations". Acta Astronautica. 32 (1): 39–49. Bibcode:1994AcAau..32...39M. doi:10.1016/0094-5765(94)90146-5. PMID 11541018.

- Webb JT; Olson RM; Krutz RW; Dixon G; Barnicott PT (1989). "Human tolerance to 100% oxygen at 9.5 psia during five daily simulated 8-hour EVA exposures". Aviat Space Environ Med. 60 (5): 415–21. doi:10.4271/881071. PMID 2730484.

- Emsley 2001, p.301

- IUPAC: Red Book. p. 73 and 320.

- Chaplin, Martin (January 4, 2008). "Water Hydrogen Bonding". Retrieved January 6, 2008.

- Maksyutenko, P.; Rizzo, T. R.; Boyarkin, O. V. (2006). "A direct measurement of the dissociation energy of water". J. Chem. Phys. 125 (18): 181101. Bibcode:2006JChPh.125r1101M. doi:10.1063/1.2387163. PMID 17115729.

- Smart, Lesley E.; Moore, Elaine A. (2005). Solid State Chemistry: an introduction (3rd ed.). CRC Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-7487-7516-3.

- Cook & Lauer 1968, p.506

- "NFPA 704 ratings and id numbers for common hazardous materials" (PDF). Riverside County Department of Environmental Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 11, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- Cook & Lauer 1968, p.511

- Wade, Mark (2007). "Space Suits". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on December 13, 2007. Retrieved December 16, 2007.

- Werley, Barry L, ed. (1991). ASTM Technical Professional training. Fire hazards in oxygen systems. Philadelphia: ASTM International Subcommittee G-4.05.

- Report of Apollo 204 Review Board NASA Historical Reference Collection, NASA History Office, NASA HQ, Washington DC

- Chiles, James R. (2001). Inviting Disaster: lessons from the edge of technology: an inside look at catastrophes and why they happen. New York: HarperCollins Publishers Inc. ISBN 978-0-06-662082-4.

- Since O

2's partial pressure is the fraction of O

2 times the total pressure, elevated partial pressures can occur either from high O

2 fraction in breathing gas or from high breathing gas pressure, or a combination of both. - No single ignition source of the fire was conclusively identified, although some evidence points to an arc from an electrical spark.[49]

General references

- Emsley, John (2001). "Oxygen". Nature's building blocks: An A-Z guide to the elements. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 297–304. ISBN 978-0-19-850340-8.

- Canfield, Donald 2014. Oxygen: a four billion year history. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14502-0

- Lane, Nick 2002. Oxygen: the molecule that made the world. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860783-0