| French occupation of Moscow | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French invasion of Russia | |||||||

The Fire of Moscow 1813 by Alexander Smirnov | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 100,000[1] | Unknown part of about 250,000 inhabitants[2] | ||||||

Location within Europe | |||||||

French Emperor Napoléon Bonaparte's Grande Armée occupied Moscow from 14 September to 19 October 1812 during the Napoleonic Wars. It marked the summit of the French invasion of Russia. During the occupation, which lasted 36 days, the city was devastated by fire and Napoleon ordered a systematic looting of the churches to fill his war chest with silver.[3]

Napoleon's invasion of Russia began on the 24th of June in 1812, and he had made considerable progress by fall. With French victory in the Battle of Borodino on 7 September, the way to Moscow was open. The opposing Russian army under Mikhail Kutuzov had suffered heavy losses and chose to retreat. A week of close escapes on the part of the Russian army followed. Napoleon and Kutuzov even slept on the same bed in the manor of Bolshiye Vyazyomy just one night apart, as the French chased the Russians down. Napoleon and his army entered Moscow on 14 September. To Napoleon's surprise, Kutuzov had abandoned the city, and it fell without a fight. Hundreds of thousands of civilians fled along with the retreating Russian army, leaving the city nearly empty.

The capture of the city was a hollow victory for the French, as the Russians—most likely on orders of governor Fyodor Rostopchin—set much of the city on fire in a scorched earth tactic (though the cause of the fire is disputed). For four days until 18 September, the city burned. The French, who had intended to pilfer the city for supplies, were now deep in enemy territory without adequate food as winter was approaching. The French thoroughly looted what had not burned, including ransacking churches. French misery was compounded by guerilla warfare by the Cossacks against French supplies, and total war by peasants. This kind of attrition war weakened the French army at its most vulnerable point: logistics.

On 19 October, after losing Battle of Tarutino, Napoleon and his Grande Armée, slowly weakened by the attrition warfare against him, lacking provisions, and facing the first snows, abandoned the city voluntarily and marched southwards until the Battle of Maloyaroslavets stopped the advance.[4] The retreating French set further fires in the city, and blew up monuments. The Russians retook the city on 19 October, and quelled rioting and looting by peasants. The destruction of the city was considerable: it would take more than half a century to return to its pre-war population.

Background

Field Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov's Russian army suffered heavy losses at the Battle of Borodino on 7 September 1812.[5][6] Before dawn of 8 September, Kutuzov ordered a retreat from Borodino eastwards to preserve the army.[7] They camped outside Mozhaysk.[8] On 10 September, the main quarter of the Russian army was situated in Bolshiye Vyazyomy,[9] in whose manor house Kutuzov stayed the night—sleeping on a sofa in the library. Russian sources suggest Kutuzov wrote a number of orders and letters to Fyodor Rostopchin about saving the city or the army.[10][7] On 11 September Napoleon wrote Marshal Victor to hurry to Moscow, worried about the already enormous losses his massive army had suffered as a result of Barclay and Kutuzov's attrition warfare against Napoleon.[11] On 12 September [O.S. 31 August] 1812 the main forces of Kutuzov departed from the village, now Golitsyno, and camped near Odintsovo, 20 km to the west. They were followed by Mortier and Joachim Murat's vanguard. On 12 September Bonaparte, who suffered from a cold and lost his voice, slept in the main manor house of Bolshiye Vyazyomy—on the same sofa in the library that Kutuzov had just the night before.[12] On 13 September Napoleon left the manor house and headed east.[13] Napoleon and Poniatovsky also camped near Odintsovo and invited Murat for dinner. In the afternoon Russian army commanders met at the village of Fili near Moscow. After a long discussion Kutuzov followed the advice of Karl Tol to retreat to the south, leading to the Battle of Maloyaroslavets with a reinforced Russian army.[14]

The French enter Moscow

General Mikhail Miloradovich, commander of the Russian rearguard, was concerned by the disposition of the army; it was stretched across Moscow, burdened with a large number of wounded and numerous convoys. Miloradovich sent Captain Fyodor Akinfov, of the Hussar Regiment's Life Guards, to open negotiations with Marshal Joachim Murat, commander of the French vanguard. Akinfov would deliver a note signed by Colonel Paisiy Kaysarov, the duty general of the General Staff of the Russian Army, stating "the wounded left in Moscow are entrusted to the humanity of the French troops",[15] and a verbal message from Miloradovich saying:[16][17]

If the French want to occupy Moscow as a whole, they must, without advancing strongly, let us calmly leave it with artillery and a convoy; otherwise, General Miloradovich will fight to the last man before Moscow and in Moscow and, instead of Moscow, will leave the ruins.

Akinfov was also to delay by staying in the French camp for as long as possible.[16][17]

On the morning of 14 September, Akinfov and a trumpeter from Miloradovich's convoy arrived at the French line just as the French were resuming their attack with cavalry.[18] They were received by Colonel Clément Louis Elyon de Villeneuve, of the 1st Horse-Jaeger Regiment, who sent Akinfov to General Horace François Bastien Sébastiani, commander of the II Cavalry Corps. Sébastiani's offer to deliver the note was refused; Akinfov said that he was ordered to personally deliver the note and a verbal message to Murat. The Russian delegation was sent to Murat.[17]

Initially, Murat rejected a compromise. To the note he replied that it was "in vain to entrust the sick and wounded to the generosity of the French troops; the French in captive enemies no longer see enemies".[19][20] Furthermore, Murat said that only Napoleon could stop the offensive, and sent the Russians to meet the emperor. However, Murat quickly changed his mind and recalled the delegation, saying that he was willing to accept Miloradovich's terms to save Moscow by advancing "as quietly" as the Russians, on the condition that the French were allowed to take the city on the same day. Murat also asked Akinfov, a native of Moscow, to persuade the city's residents to remain calm to avoid reprisals.[16][17]

Before leaving, Kutuzov had Rostopchin destroy most of Moscow's supplies as part of a scorched earth strategy; this was a different action from the famous burning of Moscow which would later destroy the city.[21]

The Grande Armée began entering Moscow on the afternoon of 14 September, a Monday, on the heels of retreating Russian army. Cavalry from the French vanguard encountered Cossacks from the Russian rearguard; there was no fighting, and there were displays of mutual respect.[22] At 14:00, Napoleon arrived at Poklonnaya Gora, 3 miles from the limits of 1812 Moscow.[lower-alpha 1] Accompanying him was the French vanguard, arrayed in battle formation by Murat's orders. Napoleon waited for half an hour; when there was no Russian response he ordered a cannon fired to signal the advance on the city. The French advanced swiftly. Infantry and artillery began entering Moscow. French troops divided before the Dorogomilovskaya gate to enter the city through other gates.

Napoleon stopped at the city walls, the Kamer-Kollezhsky rampart, about 15 minutes away from the Dorogomilovskaya gate, to wait for a delegation from Moscow. Ten minutes later, a young man told the French that the city had been abandoned by the Russian army and population. The news was met by bewilderment, and then despondency and grief. It was not until an hour later that Napoleon resumed his procession into the city, followed by the first French cavalry into Moscow. He passed the Dorogomilovskaya Yamskaya Sloboda and stopped on the banks of the Moscow River. The vanguard crossed the river; infantry and artillery used the bridge, while cavalry forded. On the opposite bank, the army broke up into small guard detachments along the river bank and streets.

Napoleon continued on with his large retinue. He was preceded by two squadrons of horse guards at a distance of a hundred fathoms, and his uniform was austere compared to those around him. The streets were deserted. On Arbat Street, Napoleon saw only a pharmacist and his family attending to a wounded French general at a stand. At the Borovitsky gate of the Kremlin, Napoleon said of the walls with a sneer: "What a scary wall!".[23]

According to contemporary accounts, Napoleon ordered food to be delivered to the Kremlin by Russians—regardless of sex, age, or infirmity—instead of by horse; this was in response to the indifference that the Russians had treated his arrival.[24][25] According to historian Alexander Martin, Muscovites generally left the city rather than accept the occupation so that most of the city was empty when the French arrived and even more Muscovites would leave while the French remained there and anywhere from 6,000 to 10,000 remained in the city[lower-alpha 2]; in addition to them around 10,000 to 15,000 wounded and sick Russian soldiers also remained.[28] For comparison, the city was calculated to host more than 270,000 inhabitants: a police survey from the beginning of 1812 found 270,184 residents.[29][25]

The frequency of looting by the French army and the local population increased as the occupation continued. Initially, looting was driven by wealth but later it was for food. Civilians were killed by troops. Attempts by French commanders to maintain discipline failed and soldiers would openly disobey the orders of their officers; as such, many French soldiers took part in these war crimes, even those of the elite Imperial Guard joining their comrades in looting and attacking civilians.[30] The locals sometimes called the French "pagans" or "basurmans" which depicted the French as godless, as the desecration of local churches was systematically done by the French army to fill Napoleon's war chest.[31][32]

Moscow Fire

Arson occurred around the city when the French entered on 14 September.[33] The French believed that Count Fyodor Rostopchin, the Moscow governor, ordered the fires, and this is the most widely accepted theory;[34][35] furthermore, Rostopchin also had all the firefighting equipment removed or disabled, making it impossible to fight the flames.[36] Strong winds, starting on the night of 15–16 September and persisting for more than a day, fanned the flames across the city. A French military court shot up to 400 citizens on suspicion of arson.

The fire worsened Napoleon's mood, though he was deeply impressed and disturbed by the Russian scorched earth policies and expressed shock and fear at them. One eyewitness recalled that the Emperor said the following about the fire: "What a terrible sight! And they did this themselves! So many palaces! What an incredible solution! What kind of people! These are Scythians!".[37]

Eventually, the intensity of the fire forced Napoleon to escape the Kremlin and relocate to the Petrovsky Palace early in the morning of 16 September as the fire surrounded him and his entourage.[38] Count Ségur described this incident as follows:

We were surrounded by a sea of flame; it threatened all the gates leading from the Kremlin. The first attempts to get out of it were unsuccessful. Finally, an exit to the Moscow River was found under the mountain. Napoleon came out through him from the Kremlin with his retinue and the old guard. Coming closer to the fire, we did not dare to enter these waves of the sea of fire. Those who managed to get to know the city a little did not recognize the streets disappearing in smoke and ruins. However, it was necessary to decide on something, because with every moment the fire intensified more and more around us. A strong heat burned our eyes, but we could not close them and had to stare forward. The suffocating air, the hot ashes and the flame of the spiral escaping from everywhere, our breath, short, dry, constrained and suppressed by smoke. We burned our hands, trying to protect our face from the terrible heat, and cast off the sparks that showered and burned the dress.[38]

Historian Yevgeny Tarle writes that Napoleon and his entourage travelled along the burning Arbat and then the relatively safe shores of the Moscow River.

The fire[lower-alpha 3] raged until 18 September and destroyed most of Moscow; the flames were reportedly visible over 215 km, or 133 miles, away.[36] Louise Fusil, a French actress, who was living in Russia for six years, witnessed the fire and offers details in her memoires.

Napoleon in Moscow

Napoleon returned to the Kremlin on 18 September where he announced his intention to remain in Moscow for the winter; he believed the city still offered better facilities and provisions. He ordered defensive preparations, including the fortification of the Kremlin and the monasteries surrounding the city, and reconnaissance beyond the city. Napoleon continued to address the empire's state affairs while in Moscow.

A municipal governing body, the Moscow municipality, was created and met at the house of Chancellor Nikolai Rumyantsev on Maroseyka 17. Dulong, a merchant, was selected to lead the body; he was instructed by Quartermaster Lesseps to choose philistines and merchants to help him. The 25 members of the municipality searched for food near the city, helped the poor, and saved burning churches. The members were not punished for collaboration after the occupation because they had been conscripted. The French created a municipal police force on 12 October.

Napoleon toured the city and nearby monasteries in near-daily sojourns. He allowed General Tutolmin, the head of the Moscow Orphanage, to write to patron Empress Maria about the conditions of the pupils; he also asked Tutolmin to communicate his desire for peace to Emperor Alexander I. Tutolmin's messenger to Saint Petersburg was allowed through French lines on 18 September. Napoleon sent two other peace proposals. Ivan Yakovlev was a wealthy landowner who remained to care for his young son Alexander Herzen and the mother; he was permitted to leave for Saint Petersburg with a letter from the French to Alexander I.[39] The last attempt was on 4 October, when General Jacques Lauriston, the pre-war ambassador to Russia, was sent to speak with Kutuzov at Tarutino; Kutuzov refused to negotiate but promised to relay proposals from Alexander I. Napoleon received no replies to any of the proposals.

Some Soviet historians (for example, Tarle) believed that Napoleon considered abolishing serfdom to pressure Alexander I and the Russian nobility.[lower-alpha 4] The occupation caused some social unrest; there were cases of serfs declaring themselves freed from their obligations to their landlords—especially those about to flee.[32]

Treatment of churches

Churches were not afforded special protections. Some housed stables, wood components were used as fuel, and others had their gold and silver items melted down.[40] After the occupation, the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin was closed to the public to hide the damage:

I was overwhelmed with horror, finding this revered temple, which spared even the flame, now put upside down the godlessness of the unbridled soldier, and made sure that the state in which it was needed to be hidden from the eyes of the people. The relics of the saints were disfigured, their tombs filled with sewage; decorations from tombs are torn off. The images adorning the church were stained and split.[41]

According to another account, rumors exaggerated the damage to churches as "most of the cathedrals, monasteries and churches were turned into guard barracks" and "no one was allowed to enter the Kremlin under Napoleon".[42][lower-alpha 5] The Russians hid some items before abandoning the city; Alexander Shakhovskoy writes: "In the Miracle Monastery there was no shrine of Saint Alexei, it was taken out and hidden by Russian piety, as well as the relics of Saint Tsarevich Demetrius, and I found only one cotton paper in the tomb".[42]

According to Shakhovskoy, the only case of desecration deliberately meant to insult was a dead horse being left in place of the throne on the altar of the Kazan Cathedral.[42]

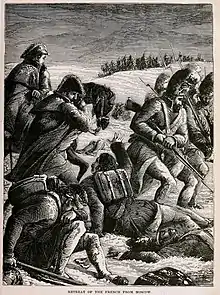

The French abandon Moscow

It was impossible to adequately provision the Grande Armée in a burnt city, with guerilla warfare by the Cossacks against French supplies and a total war by the peasants against foraging. This warfare weakened the French army at its most vulnerable point, logistics, as it had overstretched its supply lines.[4][43] "An army marches on its stomach" says Riehn.[44] The campaigning to Saint Petersburg, Russia's official capital, was out of the question as winter was closing in. The main French army's combat effectiveness had been further reduced by indiscipline and idleness. On 18 October, General Bennigsen's Russian force defeated Murat's French force at the Chernishna River in, the Battle of Tarutino. On 18 October the Second Battle of Polotsk saw another French defeat. Napoleon finally recognized that there would be no peace agreement.[4][43]

On 19 October, the main French army began moving along the Old Kaluga Road. Only Marshal Édouard Mortier's corps remained in Moscow; Mortier was the city's Governor General. Napoleon intended to attack and defeat the Russian army, and then break out into unforaged country for provisions; however, short on supplies and seeing the fall of the first snows on Moscow, the French abandoned the city voluntarily that same night.[4][45] Also that night, he made camp in the village of Troitsky on the Desna River and ordered Mortier to destroy Moscow and then rejoin the main army.

Mortier was to set fire to wine shops, barracks, and public buildings, followed by the city in general, and then the Kremlin. Gunpowder was to be placed under the Kremlin walls, which would explode after the French left the city. There was only time to partially destroy the Kremlin. The Vodovzvodnaya Tower was completely destroyed, while the Nikolskaya, 1st Bezymyannaya and Petrovskaya Towers, the Kremlin wall, and part of the arsenal were badly damaged. The explosion set the Palace of Facets on fire. The Ivan the Great Bell Tower, the city's tallest structure, survived demolition nearly unharmed, although the nearby Church of the Resurrection was destroyed.[46]

Aftermath

The advance of the French army towards the untouched Kaluga Governorate south-westwards led subsequently to the Battle of Maloyaroslavets.[47]

The Russians reoccupy Moscow

The Russian army's cavalry vanguard, commanded by General Ferdinand von Wintzingerode, was the first to re-enter the city. Wintzingerode was captured by Mortier's troops, and command fell to General Alexander von Benckendorff. On 26 October, Benckendorf wrote to General Mikhail Vorontsov:[41]

We entered Moscow on the evening of the 11th.[lower-alpha 6] The city was given for plunder to peasants, who flocked a great many, and all drunk; Cossacks and their foremen completed the rout. Entering the city with hussars and life-Cossacks, I considered it a duty to immediately take command over the police units of the unfortunate capital: people killed each other on the streets, set fire to houses. Finally, everything calmed down and the fire was extinguished. I had to endure several real battles.

Other accounts also reported crowds of peasants engaged in drunkenness, robbery and vandalism.[32][48] According to Shakhovskoy:[42]

The peasants near Moscow, of course, are the most idle and quick-witted, but the most depraved and greedy in all of Russia, assured of the enemy's exit from Moscow and relying on the turmoil of our entry, arrived on carts to capture the unlawed, but Count Benckendorf calculated differently and ordered to be loaded onto their carts and carrion and taken out of town to places convenient for burial or extermination, which saved Moscow from the infection, its inhabitants from peasant robbery, and peasants from sin.

In a report to Rostopchin dated 16 October[lower-alpha 6] from Ivashkin, the chief of the Moscow police, estimated that 11,959 human and 12,546 horse corpses were removed from the streets.[40] Upon returning to the city, Rostopchin announced that looters could keep their goods but that victims should be compensated. According to Vladimir Gilyarovsky, the next Sunday market near the Sukharev Tower was filled with looted goods. The imperial manifesto of 30 August 1814 granted amnesty for most crimes committed during the invasion.[32]

The city for its part would need at least half a century for it to be fully rebuilt and repopulated back to its pre-war levels.[49][50][51]

See also

Explanatory notes

- ↑ The official of the Russian Ministry of Finance, Fyodor Korbeletsky, who was captured by the French on August 30 and was at Napoleon's main headquarters for 3 weeks, left detailed notes on what was happening during this period. Notes by Korbeletsky "A Brief Narrative About the French Invasion of Moscow and Their Stay in It. With the Appendix of an Ode in Honor of the Victorious Russian Army" were published in Saint Petersburg in 1813.

- ↑ According to Martin, only 6,200 civilians remained.[26]; however, historian Vladimir Zemtsov calculates that 10 thousand inhabitants remained[27]

- ↑ There are several versions of the fire—organized arson when leaving the city (usually associated with the name of Fyodor Rostopchin), arson by Russian scouts (several Russians were shot by the French on such a charge), uncontrolled actions by the invaders, a random fire that spread due to the general chaos in the abandoned city. There were several pockets of fire, so it is possible that all versions are true to one degree or another.

- ↑ The rationale is that Napoleon intended to look for information about Pugachev in the Moscow archive, asked to sketch the manifesto for the peasantry, wrote to Eugène de Beauharnais, that it would be nice to cause an uprising of peasants.

- ↑ Of course, the guards did not keep order in the temples. According to Shakhovsky's recollections, "wine flowing out of broken barrels was dirty in the Archangel's Cathedral, junk was thrown out of the palaces and the Armory, among other things, two naked stuffed animals representing old armor".

- 1 2 This is by the Julian calendar.

Notes

- ↑ Riehn 1990, p. 265.

- ↑ Riehn 1990, pp. 263–264.

- ↑ Riehn 1990, pp. 285–286.

- 1 2 3 4 Riehn 1990, p. 321.

- ↑ Lieven 2009, p. 252, 6. Borodino and the Fall of Moscow.

- ↑ Haythornthwaite 2012, p. 40-72, The Battle of Borodino.

- 1 2 Lieven 2009, p. 210-211, 5. The Retreat.

- ↑ Haythornthwaite 2012, p. 74, The End of the Campaign.

- ↑ Wolzogen und Neuhaus, Justus Philipp Adolf Wilhelm Ludwig (1851). Wigand, O. (ed.). Memoiren des Königlich Preussischen Generals der Infanterie Ludwig Freiherrn von Wolzogen [Memoirs of the Royal Prussian General of the Infantry Ludwig Freiherrn von Woliehen] (in German) (1st ed.). Leipzig, Germany: Wigand. LCCN 16012211. OCLC 5034988.

- ↑ Filippov, Andrey (2013). "Большие Вязёмы [Bolshie Vyazyomy]" [Big Vyazyomy]. Великая Отечественная война 1812 года [Great Patriotic War of 1812] (in Russian). Moscow, Russia. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021 – via Образовательный центр «НИВА» [Educational Center "NIVA"].

- ↑ Chandler 2009, p. 813-822, 71. Precarious Position (Part Fourteen. Retreat).

- ↑ Architecture Best editorial staff (4 May 2020). "Усадьба Большие Вяземы" [Manor Bolshiye Vyazemy]. Архитектура - Архитектура Best/Akrhitektura - Arkhitektura Best [Architecture - Architecture Best]. History of the Moscow Region Manors (in Russian). Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ↑ Austin 2012, p. 93, Chapter 5: Settling in for the Winter.

- ↑ Riehn 1990, p. 263.

- ↑ Chuquet 1911, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 Popov 2009, p. 634–635.

- 1 2 3 4 Zemtsov 2010, p. 7–8.

- ↑ Varchi 1821.

- ↑ Kharkevich 1900, pp. 206–208.

- ↑ Zemtsov 2015, p. 233.

- ↑ Chandler 2009, p. 749-766, 68. War Plans and Preparations (Part Thirteen. The Road to Moscow).

- ↑ Zemtsov 2016, p. 224.

- ↑ Drechsler 1813, p. 109.

- ↑ Zakharov 2004, p. 161.

- 1 2 Philippart, John (1813). "Bulletins issued by Buonaparte during the Northern Campaign of 1812". In Martin, Patrick; Cumming, J.; Ballantyne, J. (eds.). Northern Campaigns. Vol. 2. London, England, United Kingdom of Great Britain: Patrick Martin and Co./J. Ballantyne and Co. pp. 340–443 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Martin 2002, p. 473.

- ↑ Zemtsov 2015, p. 244; Zemtsov 2018, p. 78–79.

- ↑ Mikaberidze, Alexander (2014). Masséna, Victor-André; Lentz, Thierry; de Bruchard, Marie; Boulant, Antoine; Delage, Irène (eds.). "Napoleon's Lost Legions. The Grande Armée Prisoners of War in Russia". Napoleonica. La Revue. Spécial prisonniers de guerre. Paris, Ile de France, France: Fondation Napoléon. 21 (3): 35–44. doi:10.3917/napo.153.0035. ISSN 2100-0123 – via Cairn.INFO.

- ↑ Zemtsov 2018, p. 78.

- ↑ Zemtsov, Vladimir Nikolaevich (8 September 2017). Soboleva, Larisa; Redin, Dmitry; Itskovich, Tatiana; Timofeev, Dmitry; Antoshin, Alexey (eds.). "Russia and the Napoleonic Wars: 200 Years Later" (PDF). Quaestio Rossica. Controversiae et recensiones. Yekaterinburg, Russia: Ural Federal University. 5 (3): 893–900. doi:10.15826/qr.2017.3.257. hdl:10995/52244. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ↑ Riehn 1990, p. 286.

- 1 2 3 4 Martin 2002.

- ↑ Zemtsov 2004.

- ↑ Austin 2012, pp. 26–28, Chapter 1: "Fire! Fire!".

- ↑ Mikaberidze 2014, pp. 145–165, Chapter 8: 'By Accident or Malice?' Who Burned Moscow.

- 1 2 Luhn, Alec (14 September 2012). Richardson, Paul E.; Widmer, Scott; Shine, Eileen; Matte, Caroline (eds.). "Moscow's Last Great Fire". Russian Life. Montpelier, Vermont, United States of America: StoryWorkz. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ↑ narod 2021.

- 1 2 "Segur's History of Napoleon's Expedition". The Literary Gazette, and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences, Etc. London, England, United Kingdom of Great Britain: Whiting & Branston. IX (431): 262–263. 23 April 1825. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Ralston, William Ralston Shedden (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 402–403, see page 402, lines two and three.

...His father, Ivan Yakovlef, after a personal interview with Napoleon, was allowed to leave, when the invaders arrived, as the bearer of a letter from the French to the Russian emperor...

- 1 2 Teplyakov 2021.

- 1 2 Benckendorf 2001, Кампания 1812 года (Campaign of 1812).

- 1 2 3 4 Shakhovskoy 1911, pp. 95, 99.

- 1 2 Wilson 2013, p. 213, Combat of Czenicznia and brilliant conduct of Murat.

- ↑ Riehn 1990, p. 138.

- ↑ Chandler 2009, pp. 813–822, 71. Precarious Position (Part Fourteen. Retreat).

- ↑ Wilson, Robert Thomas (2013) [1860]. Randolph, Herbert (ed.). Narrative of events during the Invasion of Russia by Napoleon Bonaparte, and the Retreat of the French Army, 1812. Cambridge Library Collection (3rd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108054003. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Riehn 1990, pp. 321–327.

- ↑ Bakhrushin 1913, p. 26.

- ↑ Schmidt, Albert J. (1981). Koenker, Diane P. (ed.). "The Restoration of Moscow after 1812". Slavic Review. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies (ASEEES)/University of Pittsburgh/Cambridge University Press. 40 (1): 37–48. doi:10.2307/2496426. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2496426. LCCN 47006565. OCLC 818900629. S2CID 163600450. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ↑ Mikaberidze 2014, pp. 96–111, Chapter 6: The Great Conflagration.

- ↑ Mikaberidze 2014, pp. 68–95, Chapter 5: 'And Moscow, Mighty City, Blaze!'.

References

- Philippart, John (1813). Martin, Patrick; Cumming, J.; Ballantyne, J. (eds.). Northern Campaigns. Vol. 2. London, England, United Kingdom of Great Britain: Patrick Martin and Co./J. Ballantyne and Co. – via Internet Archive.

- Haythornthwaite, Philip; et al. (Illustrations and graphics by Peter Dennis) (20 September 2012). Cowper, Marcus (ed.). Borodino 1812: Napoleon's great gamble. Campaign. Vol. 246. London, England, United Kingdom of Great Britain: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781849086974. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Google Books.

- Austin, Paul Britten (3 December 2012). 1812: Napoleon in Moscow (2nd ed.). Barnsley, England, United Kingdom of Great Britain: Frontline Books. ISBN 9781473811393. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Google Books.

- Riehn, Richard K. (1990). 1812: Napoleon's Russian campaign. New York City, New York, United States of America: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780070527317. LCCN 89028432. OCLC 20563997. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- US DOD (2021). "delaying operation".

- Chuquet, Arthur (1911). Champion, Honoré (ed.). Lettres de 1812 [Letters of 1812]. Bibliothèque de la Révolution et de l'Empire (in French). Vol. II. Paris, Ile de France, France: Libraire Ancienne – via Internet Archive.

- Varchi, Clemens Cerrini de Monte (1821). Die Feldzüge der Sachsen, in den Jahren 1812 und 1813. Dresden: Arnold.

- Kharkevich, Vladimir Nikolaevich (1900). 1812 г. в дневниках, записках и воспоминаниях современников: материалы Военно-научного архива Генерального штаба [1812 in Diaries, Notes, and Memoirs of Contemporaries: Materials of the Military Scientific Archive of the General Staff] (in Russian). Vol. 1. Vilna, Lithuania: Printing House of the Headquarters of the Vilnius Military District.

- Drechsler, Friedrich (1813). "Syn otechestva". The Son of the Fatherland, A Historical and Political Journal.

- Zakharov, Arthur (2004). Napoleon v Rossii glazami russkikh [Napoleon in Russia through the eyes of the Russians] (in Russian) (1st ed.). Moscow, Russia.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lieven, Dominic (2009). Dohle, Markus; Wright, Deborah; Weldon, Tom; Prior, Joanna (eds.). Russia Against Napoleon: The Battle for Europe, 1807 to 1814 (1st ed.). London, England, United Kingdom of Great Britain: Allen Lane (Penguin Books). ISBN 9780141947440. OCLC 419644822 – via Google Books.

- Zemtsov, Vladimir Nikolaevich (2004). Napoleon and the Fire of Moscow.

- narod (2021). "Fire in Moscow".

- Teplyakov, S.A. (2021). Nasedkin, Kirill A.; Polyakov, Oleg (eds.). ""Москва в 1812 году"" [Moscow in 1812]. МЕМУАРЫ И ПИСЬМА (MEMOIRS AND LETTERS). Музеи России. Библиотеке интернет-проекта «1812 год» (Library of the Internet Project "1812" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- Benckendorf, Konstantin Alexander Karl Wilhelm Christoph (2001) [1903]. Grünberg, P.N.; Kharkevich, V.I.; Degtyarev, Konstantin (eds.). Zapiski Benkendorfa: Otechestvennaia voina; 1813 god: Osvobozhdenie Niderlando [Benkendorff's Notes. The Patriotic War; 1813: The Liberation of the Netherlands] (in Russian) (2nd ed.). Vilna, Lithuania: Languages of Slavic Culture – via Militera.ru.

- Shakhovskoy, Alexander (1911). The First Days in Burnt Moscow. September and October 1812. According to the Notes of Prince Alexander Shakhovsky // Fire of Moscow. According to the Memoirs and Notes of Contemporaries: Part 2.

- Bakhrushin, Sergey (1913). Moscow in 1812. Edition of the Imperial Society of History and Antiquities of Russia at Moscow University.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mikaberidze, Alexander (2014). The Burning of Moscow: Napoleon's Trial By Fire 1812. Pen & Sword Military (1st ed.). Barnsley, England, United Kingdom of Great Britain: Pen & Sword Books Limited. ISBN 9781781593523 – via Google Books.

Further reading

- Tolstoy, Leon (1889) [1869]. "Contents". In Dole, Nathan Haskell; Crowell, Thomas Y. (eds.). War and Peace. Translated by Dole, Nathan Haskell. New York City: Thomas Y. Crowell & Co. – via Wikisource.

War and Peace is a novel set during the French invasion and occupation of Moscow; it is widely considered to be a classic canon of Western literature plus Tolstoy's best work and one of the best novels ever written.[1][2]

- Bourgogne, Adrien Jean Baptiste François (1899). Cottin, Paul (ed.). Memoirs of Sergeant Bourgogne, 1812–1813 (2nd ed.). New York City: Doubleday & McClure Company. LCCN 99001646. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- Chandler, David G.; et al. (Graphics and illustrations by Shelia Waters, design by Abe Lerner) (2009) [1966]. Lerner, Abe (ed.). The Campaigns of Napoleon: The mind and method of history's greatest soldier. Vol. I (4th ed.). New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1439131039. OCLC 893136895. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Google Books.

- Chambray, George de, Histoire de l'expédition de Russie

- Franceschi, Michel; Weider, Ben (2008). The wars against Napoleon: Debunking the myth of the Napoleonic Wars. Translated by House, Jonathan M. (2nd ed.). New York City: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1611210293. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Google Books.

- Zamoyski, Adam (2004) [1980]. Moscow 1812: Napoleon's Fatal March (2nd ed.). New York City: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0061075582. LCCN 2004047575. OCLC 55067008. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- Tartakovski, Andrei G. (1995) [1971]. Tartakovsky, R. (ed.). 1812 god v vospominaniyah sovremennikov [1812 in the memoirs of contemporaries] (in Russian) (2nd ed.). Moscow: Institute of Russian History of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

- Tartakovsky, Andrei G. (1973). Sidorov, Arkady (ed.). "Население Москвы в период французской оккупации" [The population of Moscow during the French occupation]. Istoricheskie Zapiski (in Russian). Moscow: Institute of History of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union/Progress Publishers. 36 (92): 356–379. ISSN 0130-6685. OCLC 1754039.

- Muravyov, Nikolay, Notes, Russian Archive, 1885, No. 9, p. 23

- Pravda, The French in Moscow, Russian Memoirs, 1989, pp. 164–168

- Fedor Korbeletsky. A Short Story About the French Invasion of Moscow and Their Stay in It. With the Application of an Ode in Honor of the Victorious Russian Army – Saint Petersburg. 1813

- Zemtsov, Vladimir Nikolaevich (2010). 1812 Year. Moscow Fire. 200-летие Отечественной войны 1812 г. (200th Anniversary of the Patriotic War of 1812). Moscow. p. 138. ISBN 978-5-91899-013-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Zemtsov, Vladimir Nikolaevich (30 September 2016). Soboleva, Larisa; Redin, Dmitry; Itskovich, Tatiana; Timofeev, Dmitry; Antoshin, Alexey (eds.). "МОСКВА ПРИ НАПОЛЕОНЕ: СОЦИАЛЬНЫЙ ОПЫТ КРОССКУЛЬТУРНОГО ДИАЛОГА" [Moscow Under Napoleon: The Social Experience of Cross-Cultural Dialogue] (PDF). Vox redactoris. Quaestio Rossica (in Russian). Yekaterinburg, Russia: Ural Federal University. 4 (3): 217–234. doi:10.15826/qr.2016.3.184. hdl:10995/41238. ISSN 2311-911X. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- Zemstov, Vladimir Nikolaevich (2014). Наполеон в Москье [Napoleon in Moscow]. 200-летие Отечественной войны 1812 г. (200th Anniversary of the Patriotic War of 1812) (in Russian). Moscow: Медиа-Книга. ISBN 978-5-91899-071-1. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- Zemtsov, Vladimir Nikolaevich (2018). Napoleon in Russia: The Sociocultural History of War and Occupation. The Era of 1812. Moscow: ROSSPEN. p. 431. ISBN 978-5-8243-2221-7.

- Zemtsov, Vladimir Nikolaevich. Napoleon and the Fire of Moscow // Patriotic War of 1812. Sources. Monuments. Problems. pp. 152–162

- Zemtsov, Vladimir Nikolaevich (15 August 2015). Glantz, David (ed.). "The Fate of the Russian Wounded Abandoned in Moscow in 1812". The Journal of Slavic Military Studies. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies/Taylor & Francis or Routledge. 28 (3): 502–523. doi:10.1080/13518046.2015.1061824. ISSN 1351-8046. LCCN 93641610. OCLC 56751630. S2CID 142674272.

- Nikolay Kiselev. The Case of Officials of the Moscow Government, Established by the French, in 1812 // Russian Archive, 1868 – 2nd Edition – Moscow, 1869 – Columns 881–903

- Moscow Monasteries During the French Invasion. A Modern Note for Presentation to the Minister of Spiritual Affairs, Prince Alexander Golitsyn // Russian Archive, 1869 – Issue 9 – Columns 1387–1399

- Pavlova, Maria; Rozina, Olga (27 April 2018). Moscow City Administration During the French Occupation (September–October 1812). 1st All-Russian Scientific-Practical Conference Dedicated to the Day of Local Self-Government. Actual Issues of Local Self-Government in the Russian Federation: A Collection of Scientific Articles Based on the Results of the 1st All-Russian Scientific–Practical Conference Dedicated to the Day of Local Self-Government. Vol. II. Sterlitamak, Russia: Publishing House of the Sterlitamak Branch of Bashkir State University. pp. 92–97.

- Popov, Alexander Nikolaevich (2009) [1905]. Nikitin, Sergey; Grosman, N.I.; Wendelstein, G.A. (eds.). Patriotic War of 1812 (PDF). Russian historical library (in Russian). Vol. II (7th ed.). Moscow. ISBN 978-5-902073-70-3 – via Boris Yeltsin Presidential Library.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Reman, Osip Osiopovich (23 December 1812). "Page 16". In Selivanovsky, S. (ed.). Глас Московского жителя [The voice of a Moscow inhabitant] (PDF) (in Russian). Printing house of S. Selivanovsky. Retrieved 26 September 2021 – via Wikisource.

- Yevgeny Tarle, Chapter 13. Napoleon's Invasion of Russia in 1812 // Napoleon

- Shalikov, Pyotr (1813). Историческое известие о пребывании в Москве французов 1812 года (Шаликов) [Historical news about the stay of the French in Moscow in 1812] (in Russian). Moscow, Russia. p. 64 – via Wikisource.

- Martin, Alexander M. (1 November 2002). "The Response of the Population of Moscow to the Napoleonic Occupation of 1812". In Lohr, Eric; Poe, Marshall (eds.). The Military and Society in Russia: 1450–1917. History of warfare. Vol. XIV (1st ed.). Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. pp. 469–490. ISBN 978-9004122734.

External links

Media related to French occupation of Moscow at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to French occupation of Moscow at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Battle of Borodino |

Napoleonic Wars French occupation of Moscow |

Succeeded by Siege of Burgos |

- ↑ Thirlwell, Adam (8 October 2005). Rusbridger, Alan (ed.). "A masterpiece in miniature". The Guardian. Books. London: Guardian Media Group (GMG) (Scott Trust Limited). ISSN 1756-3224. OCLC 60623878. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ↑ Freeborn, Richard (1992) [1989]. "6 – The nineteenth century: the age of realism, 1855–80". In Moser, Charles (ed.). The Cambridge History of Russian Literature. Cambridge Histories Online (5th ed.). New York City: Cambridge University Press. pp. 248–332. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521415545.007. ISBN 978-0521425674 – via Google Books.