| Battle of Prenzlau | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Fourth Coalition | |||||||

Capitulation of Prenzlau by Simeon Fort (1793–1861). | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 12,000, 12 guns | 10,000[1]-12,000, 64 guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Slight |

3,500 killed or captured in battle 10,000 surrendered[1] 64 guns | ||||||

In the Battle of Prenzlau or Capitulation of Prenzlau on 28 October 1806 two divisions of French cavalry and some infantry led by Marshal Joachim Murat intercepted a retreating Prussian corps led by Frederick Louis, Prince of Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen. In this action from the War of the Fourth Coalition, Hohenlohe surrendered his entire force to Murat after some fighting and a parley. Prenzlau is located about 90 kilometers north of Berlin in Brandenburg.

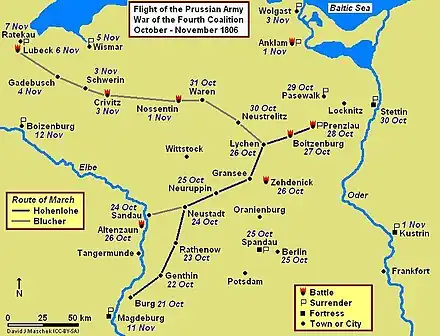

After their catastrophic defeat at the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt on 14 October, the Prussian armies fled north to the Elbe River with Emperor Napoleon I of France's victorious army in hot pursuit. The Prussians crossed the Elbe near Magdeburg and marched northeast, trying to reach safety behind the Oder River. Part of Napoleon's army thrust east to seize Berlin, while the rest followed the retreating Prussians. From Berlin, Murat moved north with his cavalry, trying to head off Hohenlohe.

After several clashes on 26 and 27 October, Murat arrived at Prenzlau on the heels of Hohenlohe's corps. Fighting occurred in which several Prussian units were captured or cut to pieces. Murat then bluffed the demoralized Hohenlohe into surrendering his entire corps by claiming that the Prussians were surrounded by overwhelming forces. In fact, apart from a brigade of infantry, only Murat's cavalry were in the vicinity. In the days afterward, the French cowed several more Prussian forces and fortresses into surrendering. Finding its way to the northeast blocked, a second corps of retreating Prussians under Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher veered northwest toward Lübeck.

Background

Jena-Auerstadt

On 8 October 1806, Napoleon's 180,000-strong army invaded the Electorate of Saxony through the Franconian Forest. His troops were massed in a batallion carré (battalion square) made up of three columns of two army corps each, plus the Imperial Guard, the Cavalry Reserve, and a Bavarian contingent.[2]

Opposing the French army were three semi-independent Prussian-Saxon armies, the first led by Feldmarschall Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick, the second under General of Infantry Frederick Louis, Prince of Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen, and the third co-commanded by General of Infantry Ernst von Rüchel and Lieutenant General Blücher.[3] Brunswick held a position at Erfurt in the center. Hohenlohe took station near Rudolstadt in the east, with General-Major Bogislav Friedrich Emanuel von Tauentzien at Hof. Rüchel was at Gotha, and Blücher held Eisenach at the western end of the line with General Karl August, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach's division near Meiningen and General Christian Ludwig von Winning at Vacha. Eugene Frederick Henry, Duke of Württemberg's Reserve lay far to the north at Magdeburg.[4]

Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte's I Corps and Murat's cavalry defeated Tauentzien's division at the Battle of Schleiz.[5] The next day, Marshal Jean Lannes' V Corps mauled the 8,300-man division of Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia at the Battle of Saalfeld, where the young prince was slain.[6] On 12 October, Napoleon wheeled his batallion carré to the left to engage his enemies in combat. In the face of this menace, Brunswick elected to march the main army north from Weimar to Merseburg, while Hohenlohe defended his flank near Jena.[7] Rüchel was at Weimar, waiting for Saxe-Weimar to return with his division.[8] The double Battle of Jena-Auerstedt occurred on 14 October as Napoleon's 96,000 troops attacked Hohenlohe and Rüchel's 53,000 at Jena,[9] while Brunswick's 49,800 troops encountered the 26,000-man III Corps of Marshal Louis Davout at Auerstedt.[10] The Prussian armies were beaten and driven from both battlefields. Brunswick's army lost 13,000 casualties and 115 artillery pieces, while the casualties of Hohenlohe and Rüchel may have reached 25,000.[11]

Retreat west of the Elbe

.jpg.webp)

In Capitulation of Erfurt on 16 October, over 10,000 Prussians laid down their arms in the first of a series of shameful surrenders. The 12,000-man corps of Saxe-Weimar and Winning missed Jena-Auerstedt and remained intact, heading north through Bad Langensalza.[12] Shot through both eyes at Auerstadt, Brunswick died on 10 November at Altona near Hamburg.[13] Dangerously wounded at Jena, Rüchel escaped to Poland and later recovered.[14] Filling the command void were Hohenlohe, General of Infantry Friedrich Adolf, Count von Kalckreuth, and Blücher, who each led sizable bodies of Prussians from Nordhausen through the Harz Mountains to Halberstadt and Quedlinburg. These columns were energetically pursued by Marshal Nicolas Soult's IV Corps with General of Division Louis Michel Antoine Sahuc's dragoons attached.[15] On 17 October, Bernadotte inflicted heavy losses on Eugene of Württemberg's Reserve at the Battle of Halle.[16]

By 20 October, Hohenlohe and the survivors of the Reserve reached Magdeburg. Kalckreuth crossed the Elbe at Tangermünde before handing over his command in order to take up a new post in Poland.[17] Blücher was east of Brunswick marching for the Elbe with Saxe-Weimar a day's march behind him at Salzgitter[18] On the 20th, Soult and Murat arrived before Magdeburg. Murat sent his chief of staff Augustin Daniel Belliard to demand its surrender, which was refused by Hohenlohe. However, the Prussians foolishly allowed Belliard into the city without a blindfold. He reported back to Murat that Hohenlohe's main body was still in the city and that great confusion prevailed.[17] Davout seized Wittenberg on the 20th, with the local people assisting his troops in putting out a fire and preventing a powder magazine from being blown up. Consequently, 140,000 pounds of gunpowder and a valuable Elbe River crossing fell into French hands. Lannes seized a second bridgehead at Dessau.[19]

Retreat east of the Elbe

Leaving Marshal Michel Ney's VI Corps to begin the Siege of Magdeburg, Napoleon ordered his right wing to head for Berlin. The French emperor found time to pay a reverent visit to the tomb of Frederick the Great at Potsdam. In spite of his respect for the Prussian king, Napoleon stole Frederick's sword and other trophies.[20] The French right wing consisted of Davout's corps, Lannes' corps, Marshal Pierre Augereau's VII Corps, and Murat's 1st Cuirassier Division under General of Division Etienne Marie Antoine Champion de Nansouty, 2nd Cuirassier Division led by General of Division Jean-Joseph Ange d'Hautpoul, and 3rd Dragoon Division under General of Division Marc Antoine de Beaumont. General of Division Emmanuel Grouchy's 2nd Dragoon Division trailed behind. Bernadotte, Soult, and Sahuc's 4th Dragoon Division formed the left wing. Louis Klein's 1st Dragoon Division was split between assisting Ney and patrolling the line of communications. Smith supplied the cavalry division numbers.[21]

Under orders from King Frederick William III of Prussia to march for the Oder, Hohenlohe's corps set out from Magdeburg on the morning of 21 October. He reinforced the garrison with 9,000 men, but in the confusion other units and 39 field guns stayed in the fortress so that 25,000 troops were left behind. That evening, Hohenlohe reached Burg bei Magdeburg where he gathered up Kalckreuth's column.[22] His main body arrived at Genthin on the evening of the 22nd and Rathenow at nightfall on the 23rd. In order to feed his troops better, he split his command up into several columns.[23]

On the 24th, Blücher crossed the Elbe at Sandau,[18] while Saxe-Weimar crossed there after deceiving Soult into believing he was heading for Magdeburg. During the operation, Oberst Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg fought a successful rear guard action at Altenzaun on the 26th. Once the column was safely on the east bank of the Elbe, Saxe-Weimar was relieved by Winning in command.[24] Hohenlohe reached Neustadt an der Dosse on the 24th. He sent out General-Major Christian Ludwig Schimmelpfennig toward Fehrbellin, between Neustadt and Oranienburg, and site of a 1675 battle. Schimmelpfennig's task was to cover his right flank and keep the French from interfering with the main body's march to Szczecin (Stettin) on the Oder. Hohenlohe gave Blücher command of his rear guard.[25]

.jpg.webp)

The dilapidated fortress of Spandau[26] fell on 25 October to General of Division Louis Gabriel Suchet's division of Lannes' corps. The commandant Major Benekendorf was discussing terms with the French when they rushed the gate and broke into the fortress. Altogether, 71 cannon and 920 soldiers, including the 3rd battalion of the König Infantry Regiment #18, three companies of soldiers unfit for field duty, and 65 gunners surrendered, the garrison being released on parole. In 1808, Benekendorf was hauled before a court-martial and condemned to be shot, but the king commuted his sentence to life in prison.[27]

On 25 October, Davout's corps marched through Berlin in triumph.[28] That evening, Hohenlohe's main body was between Neuruppin and Lindow, Blücher's rear guard division at Neustadt, Oberst von Hagen's infantry and General-Major von Schwerin's[lower-alpha 1] cavalry at Wittstock, and General-Major Rudolph Ernst Christoph von Bila's brigade at Kyritz, just north of Neustadt. Napoleon sent Murat and Lannes marching north from Berlin to intercept Hohenlohe. General of Brigade Antoine Lasalle's light cavalry and Grouchy's dragoons were already at Oranienburg with General of Brigade Édouard Jean Baptiste Milhaud's light cavalry nearby.[29]

Lasalle overtook Schimmelpfennig's 1,300 troops at Zehdenick around noon on 26 October. At first, the Prussians held back the French, but the dragoon divisions of Grouchy and Beaumont soon arrived. The Königin Dragoons # 5, four squadrons strong, charged and drove back Lasalle's hussars, but Grouchy's dragoons intervened and nearly wiped out the regiment. The Prussians lost one color and 14 officers and 250 men killed, wounded, or captured. Pursued by the French until evening, Schimmelpfennig's crippled force fled to Stettin.[27][30] Hearing of this setback, Hohenlohe changed his line of march from Gransee farther north through Lychen. On the morning of the 27th he waited at Lychen for Blücher and Bila. Since neither turned up, his column set out for Boitzenburg.[31]

As Hohenlohe neared Boitzenburg on the 27th, he met Graf von Arnim who notified him that he had collected supplies for the hungry soldiers at his manor, the Schloss Boitzenburg. Unfortunately, when the Prussians arrived around 2:00 PM they found that Milhaud's cavalrymen got there first and were pillaging the estate. It took Hohenlohe's advanced guard three hours to drive Milhaud's brigade out of the town. In the meantime, Murat heard the sound of the battle and hurried north with Grouchy's dragoons. South of Boitzenburg at Wichmannsdorf, Hohenlohe's right flank guard blundered into Grouchy's column. Three regiments of French dragoons drove the Prussian Gensdarmes Cuirassier Regiment # 10 against a marsh and forced its surrender. But without infantry, Murat was unable to halt Hohenlohe's column from hurrying past toward Prenzlau.[32]

Battle

After the clash at Boitzenburg, Hohenlohe knew that the French were on the Berlin highway, which went northeast from Zehdenick to Prenzlau. So instead of continuing on the Lychen-Boitzenburg-Prenzlau road, which intersected with the Berlin highway, he veered northeast to Schönermark-Nordwestuckermark. At 4:00 AM on 28 October and the column reached Schönermark, only eight kilometers from Prenzlau. Hohenlohe held a council of war at which the officers argued whether to march east to Prenzlau or to go north to Pasewalk. A cavalry vedette reported that Prenzlau was clear of the French at 6:00 AM, so the march continued, though three hours were wasted before getting underway. It was very difficult to get the column moving again and angry protests were heard from the starving soldiers. Schwerin led the column with a cuirassier regiment and a battery of horse artillery. The bulk of the infantry trailed behind Schwerin's vanguard and Oberst Prince Augustus of Prussia led the rear guard, which consisted of a cavalry regiment and an infantry battalion. Two dragoon regiments protected the right flank.[33]

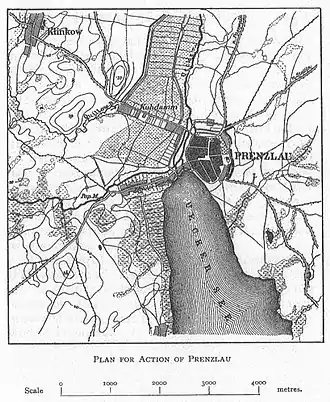

Two roads approached the west side of Prenzlau, the Berlin highway to the southwest and the road through Schönermark to the northwest. The two roads entered the city at gates about 500 meters apart. The roads were raised above the surrounding marshland and passed through suburbs about one kilometer in length. The several kilometer long Unteruckersee (Lower Ucker Lake) lies on the south side of the city. The Uecker River flows north from the lake on the west side of Prenzlau.[34]

Marshal Murat had two divisions and two brigades of cavalry, plus 12 guns in three horse artillery batteries. Lasalle's brigade included the 5th and 7th Hussar Regiments, and Milhaud's brigade comprised the 1st Hussar and 13th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiments. Grouchy's 2nd Dragoon Division had the 3rd, 4th, 10th, 11th, 13th, and 22nd Dragoon Regiments, 24 squadrons. Beaumont's 3rd Dragoon Division was made up of the 5th, 8th, 12th, 16th, 19th, and 21st Dragoon Regiments, 24 squadrons. The total French strength was 12,000 men. Smith puts all the light cavalry in Lasalle's division on page 227, but on page 228 he separates them into brigades under Lasalle and Milhaud.[35] Another authority wrote that Milhaud's brigade consisted of the 13th Chasseurs and a dragoon regiment,[36] and that 3,000 of Lannes' picked infantry were at hand.[34]

Hohenlohe's command included the Rabiel, Schack, Dohna, Osten, Borcke, Losthin, and Hahn Grenadier battalions, and the 1st battalion Arnim Infantry Regiment # 13, 1st battalion Garde Infantry Regiment # 15, König Infantry Regiment # 18, Brunswick Infantry Regiment # 21, Möllendorf Infantry Regiment # 25, Grawert Infantry Regiment # 47, Cuirassier Regiment # 3, Leib Cuirassier Regiment # 5, Prittwitz Dragoon Regiment # 2, Krafft Dragoon Regiment # 11, Wobeser Dragoon Regiment # 14. The field artillery included one horse and two 12-pounder foot batteries. Altogether, the Prussians had about 10,000 soldiers, 64 guns, and 1,800 horses for the cavalry and artillery.[37]

As Hohenlohe marched along the Schönermark road, his troops kept bumping into French patrols in the morning mist. As the column passed through the marshes, the dragoon flankers returned to the main road and pushed their way into the line of march. This spread the column out over a greater distance. Lasalle tried to block the Prussian approach march in the suburb, but Schwerin's cuirassiers brushed the French hussars out of the way. Hohenlohe directed his troops to move through the city and draw rations from a wagon train parked on the other side of Prenzlau. To cover his march, Hohenlohe posted General-Major von Tschammer[lower-alpha 2] with two grenadier battalions across the Berlin highway with their battalion guns trained on the road. Smaller detachments guarded the lake shore, the town gate, and a paper-mill.[38]

At this time, French Captain Hugues appeared out of the mist with a flag of truce and was taken to Hohenlohe. Hugues spun "a wonderful tissue of lies", claiming that Murat had 30,000 troops at hand and that Lannes with 60,000 more lurked on the road to Stettin. He insisted that the Prussian general surrender, which Hohenlohe refused to do. However, he sent his chief of staff Oberst Christian Karl August Ludwig von Massenbach back with Hugues, apparently to see what he could find out.[39]

Murat then launched his attack, Lasalle's hussars leading the way, followed by Grouchy's dragoons, while Beaumont brought up the rear. The French horse artillery rapidly silenced Tschammer's cannons. In order to harass the rear of Hohenlohe's column, the French marshal detached one of Beaumont's brigades and placed it under the command of his aide-de-camp Colonel Louis Chrétien Carrière Beaumont. Murat sent it circling to the left through the hamlet of Göllmitz on the Boitzenburg road. Murat then ordered General of Brigade André Joseph Boussart's brigade from Grouchy's division to attack the Prussian column of march. After fording a small stream west of the town, Boussart's dragoons smashed into Hohenlohe's marching column from the south. The cavalrymen overran a substantial part Hohenlohe's troops and captured Tschammer. The Prussians were forced into Prenzlau, leaving eight guns and many prisoners in French hands. Cut off, the rear guard was set upon from two directions by both Beaumont's division and Beaumont's brigade and driven northward. After trapping his command against the Uecker, the two Beaumonts compelled Prince Augustus to surrender.[40] Marching to the sound of the guns, Milhaud's brigade observed the prince's capture before continuing north to Pasewalk.[36]

Grouchy's dragoons broke down the town gate and trotted through Prenzlau and out the other side to view Hohenlohe's 10,000 troops drawn up on the road to Pasewalk. Murat sent Belliard to demand Hohenlohe's surrender, which the Prussian declined again. By this time some of Lannes' infantry were on the field. Together with Grouchy and Lasalle (but not Beaumont), there were only 4,000 to 5,000 French confronting the Prussians. At this time, Massenbach was allowed to return to the Prussian lines. Completely deceived by the French, Massenbach reported to Hohenlohe that their enemies were now between them and Stettin. Murat asked for a head-to-head parley with Hohenlohe which was granted. The marshal lied to Hohenlohe on his "word of honor" that he was surrounded by 100,000 French in the corps of Lannes, Soult, and Bernadotte.[41]

When a munitions wagon blew up in the distance, a quick-witted French officer explained that it was Soult's signal gun announcing that he was now blocking the Prussians' retreat route. Hohenlohe requested terms. These were harsh, with the officers and the Royal Guards being released on parole and the rank and file being made prisoners. After consulting with his officers, the Prussian prince surrendered his entire corps.[42]

Result

Historian Digby Smith stated that 10,000 Prussian troops, 1,800 cavalry horses, and 64 guns fell into French hands, while Murat's cavalry suffered few casualties.[37] Francis Loraine Petre noted that the Prussians' total losses were nearly 12,000, with Hohenlohe surrendering 10,000, Boussart's brigade killing or capturing 1,000, and Beaumont's division accounting for the 1,000-man rear guard. Between Prenzlau and the fighting at Boitzenburg and Zehdenick, the Prussians lost nearly 13,500 men. Beaumont was given responsibility for escorting the prisoners. Evidently some escaped, because Beaumont reported his captives numbered 9,534, not counting the approximately 400 paroled officers.[43]

Hohenlohe's capitulation proved to be a bad precedent to a subsequent string of abject Prussian surrenders in the next few days.[43] In the Capitulation of Pasewalk on 29 October, 4,000 Prussians surrendered to a force smaller than their own. Soon afterward, in the Capitulation of Stettin, Lasalle's light cavalry brigade bluffed the fortress commandant into surrendering his 5,000-man garrison.[44] Since Auerstedt, Blücher had carefully preserved an artillery convoy. But on 30 October, Major von Höpfner surrendered with 600 soldiers and 25 guns to some of Lannes' units at Boldekow, 14 kilometers south of Anklam. On 1 November, the fortress of Küstrin capitulated to General of Brigade Nicolas Hyacinthe Gautier's brigade of Davout's corps. A French dragoon brigade caught up with the 1,100 infantry and 1,073 cavalry of Bila at Anklam. Smith asserted that the brigade was from Sahuc's 4th Division but Petre stated on page 264 that Sahuc was at Rathenow on 1 November.[45] Bila had been joined by his older brother Karl Anton Ernst von Bila with a battalion from Hanover. On 31 October, General of Division Nicolas Léonard Beker forced them to withdraw to the north side of the Peene River and convinced them to capitulate the next day.[46]

After Prenzlau, Blücher's escape path to the northeast was blocked. At Neustrelitz he swung his columns to the northwest and raced toward Lübeck. By this time, Winning's division joined him to raise his total strength to 22,000 men.[44] The Battle of Lübeck occurred on 6 November.[47]

Petre believed that Hohenlohe's surrender was unnecessary and his chief of staff Massenbach was partly responsible. He thought that the Prussians could have fought their way into Stettin, and probably would have if a strong-willed general like Blücher had been in command. The brigades of Hagen and Bila were not far away at the time and these forces might have helped prevent Murat from encircling Hohenlohe.[48] Petre listed several criticisms of Hohenlohe. First, he marched too slowly from Burg and took too many detours to the north at the incompetent Massenbach's advice. It might have been possible for him to reach Prenzlau a day earlier, in which case he would have escaped Murat. Second, he kept too much cavalry and Hagen's infantry brigade on his left flank, where there were no enemies. Only Schimmelpfennig's weak brigade of 1,300 men was in the critical sector on the right flank. Third, his best troops marched in the rear guard with Blücher, while the major threat was on the right flank.[49]

Portraits

Duke of Brunswick

Duke of Brunswick Emmanuel Grouchy

Emmanuel Grouchy Friedrich Kalckreuth

Friedrich Kalckreuth Augustin Belliard

Augustin Belliard Duke of Saxe-Weimar

Duke of Saxe-Weimar Édouard Milhaud

Édouard Milhaud.jpg.webp) Frederick William III

Frederick William III

Explanatory notes

- ↑ According to the Lexicon, there are three Schwerin candidates, Philipp Adolf (1738–1815), Friedrich Wilhelm Felix (1740–1809), and Friedrich August Leopold Karl (1750–1836).

- ↑ According to the Lexicon. there are two Tschammer candidates, Friedrich Wilhelm Alexander (1737–1809) and Ernst Adolf Ferdinand (1739–1812).

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Bodart 1908, p. 374.

- ↑ Chandler 1966, pp. 467–468.

- ↑ Chandler 1966, p. 456.

- ↑ Chandler 1966, p. 459.

- ↑ Petre 1993, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Chandler 1966, pp. 470–471.

- ↑ Chandler 1966, pp. 472–473.

- ↑ Petre 1993, p. 139.

- ↑ Petre 1993, p. 147.

- ↑ Petre 1993, p. 150.

- ↑ Chandler 1979, pp. 214–216.

- ↑ Petre 1993, p. 195.

- ↑ Petre 1993, p. 159.

- ↑ Petre 1993, p. 197.

- ↑ Petre 1993, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Smith 1998, pp. 226–227.

- 1 2 Petre 1993, p. 218.

- 1 2 Petre 1993, p. 231.

- ↑ Petre 1993, pp. 219–220.

- ↑ Chandler 1966, p. 499.

- ↑ Petre 1993, pp. 224–229.

- ↑ Petre 1993, p. 226.

- ↑ Petre 1993, p. 234.

- ↑ Petre 1993, pp. 232–233.

- ↑ Petre 1993, pp. 236–237.

- ↑ Petre 1993, p. 237.

- 1 2 Smith 1998, p. 227.

- ↑ Chandler 1966, p. 500.

- ↑ Petre 1993, p. 238.

- ↑ Petre 1993, p. 239.

- ↑ Petre 1993, p. 240.

- ↑ Petre 1993, p. 242.

- ↑ Petre 1993, pp. 242–243.

- 1 2 Petre 1993, p. 243.

- ↑ Smith 1998, pp. 227–228.

- 1 2 Petre 1993, p. 252.

- 1 2 Smith 1998, p. 228.

- ↑ Petre 1993, p. 244.

- ↑ Petre 1993, p. 245.

- ↑ Petre 1993, pp. 245–246.

- ↑ Petre 1993, pp. 246–247.

- ↑ Petre 1993, pp. 248–249.

- 1 2 Petre 1993, p. 250.

- 1 2 Chandler 1966, p. 501.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 229.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 254.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 231.

- ↑ Petre 1993, p. 251.

- ↑ Petre 1993, pp. 304–306.

References

- Bodart, Gaston (1908). Militär-historisches Kriegs-Lexikon (1618-1905) (in German). Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- Chandler, David (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York: Macmillan.

- Chandler, David (1979). Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-523670-9.

- Petre, F. Loraine (1993). Napoleon's Conquest of Prussia 1806. London: Lionel Leventhal Ltd. ISBN 1-85367-145-2.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

Further reading

- Chandler, David (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 9780025236608. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

External links

The following websites are excellent sources for the full names of French and Prussian generals.

- Broughton, Tony. napoleon-series.org Generals Who Served in the French Army during the Period 1792-1815

- (in German) Montag, Reinhard. lexikon-deutschegenerale.de Lexikon der Deutschen Generale

Media related to Battle of Prenzlau at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Prenzlau at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Siege of Magdeburg (1806) |

Napoleonic Wars Battle of Prenzlau |

Succeeded by Capitulation of Pasewalk |