The island in March 2023, as seen from Strawberry. | |

Aramburu Island  Aramburu Island  Aramburu Island | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

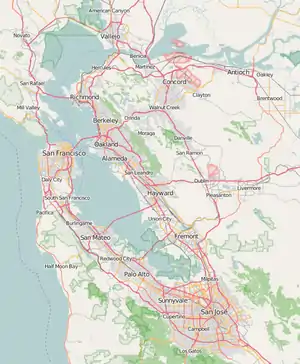

| Location | Northern California |

| Coordinates | 37°53′29″N 122°30′8″W / 37.89139°N 122.50222°W |

| Adjacent to | Richardson Bay |

| Area | 17 acres (6.9 ha)[1] |

| Administration | |

United States | |

| State | California |

| County | Marin |

Aramburu Island is a 17-acre (6.9 ha) island in Richardson Bay, Marin County, California. It, along with Strawberry Spit, came to exist in the 1950s and 1960s as a consequence of dumping dredged material from nearby developments into the bay. In the 1980s, the northern part of the landmass was cut off from Strawberry Spit on the directions of a Marin County supervisor to prevent housing from being constructed there, creating Aramburu Island. While natural erosion processes caused it to shrink slowly over the course of subsequent decades, a 2010s restoration effort added large amounts of material to prevent further erosion, and turned it into "sustainable bird habitat".[2][3]

Location and access

Aramburu Island is in Richardson Bay,[4] an embayment of San Francisco Bay to the north and northwest of Golden Gate. Its coordinates are 37°53′29″N 122°30′8″W / 37.89139°N 122.50222°W. Across the waters of Richardson Bay, it is surrounded on the south, west, north, and northeast by the unincorporated community of Strawberry. Approximately one mile (1.6 km) to the east lies the Tiburon Peninsula (and Tiburon itself). To the south, a channel separates it from Strawberry Spit.[4] The island is not easily visible from nearby roads; according to Marin Magazine, "the only folks who have a view of Aramburu Island are some of the residents of Strawberry".[4]

The island is a nature reserve, and accordingly, access is restricted; it is accessible only by boat.[3] In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic in California began to present a transmission risk for gatherings; with many indoor recreation options closed, crowds gathered instead in public parks, violating social distancing guidelines. In light of this, the Public Health Division of the Marin County Department of Health and Human Services issued an order to shut down all outdoor parks and open space preserves on March 22 of that year.[5] This order was modified on March 31, to make it illegal to drive to any park or recreational area.[6] The order was lifted for some parks on May 17,[7] and for all parks on June 1.[8] During the months of May-August, Aramburu Island and its surrounding areas became a popular hangout spot for teenagers.

Creation

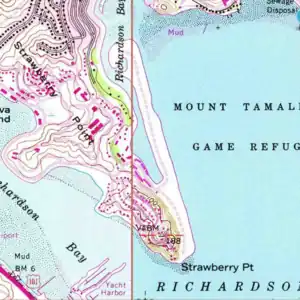

1955 USGS map

1955 USGS map 1980 USGS map

1980 USGS map 1999 USGS map

1999 USGS map

The land that now constitutes Aramburu Island and Strawberry Spit was created between the late 1950s[4] and early 1960s, from large amounts of waste material being dumped into Richardson Bay.[9] This material came from dredging operations to enlarge canals, as well as from housing developments on Strawberry Point.[9]

Aramburu Island and Strawberry Spit, while formed as one contiguous landmass, were separated in the early 1980s.[4] Al Aramburu, a Marin County supervisor, ordered a channel to be cut between Strawberry Spit and what then became Aramburu Island, because he "did not think any homes should be built" there.[4] When Aramburu Island was initially cut off from Strawberry Spit, it comprised 34 acres (14 ha).[4] However, over the course of the next several decades, coastal erosion processes caused the eastern shore of the island to recede by more than 130 feet (40 m), reducing it to its present area of 17 acres (6.9 ha).[9] The resulting landmass was described as "decidedly unromantic" and "really just a giant pile of dirt".[10]

Enhancement

In November 2007, a collision between the container ship M/V Cosco Busan and the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge resulted in a 53,569-U.S.-gallon (202,780 L)[1] fuel oil spill; it is estimated that nearly seven thousand birds were killed as a result.[11] Subsequently, the ship's owner and operator reached a settlement in which more than $32 million was to fund habitat restoration projects in the area.[11] Of this, approximately $2.4 million (equivalent to $3.39 million in 2022) went towards Aramburu Island.[10] Subsequent work, constituting a $4.2 million (equivalent to $5.93 million in 2022) overall expense,[4] involved the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the California Regional Water Quality Control Board, Marin County, the Sewer Agency of Southern Marin, and the Marin Community Foundation.[4]

At the time, Aramburu Island, along with nearby Pickleweed Island and Unnamed Island, were "virtually unknown".[12] However, in 2011, Marin County began a project to engineer a new beach, using gravel barriers that were more resistant to erosion.[9] The work, which began in the summer,[4] started with cutting back slopes on the east side of the island that had become unstable.[9] Then, a "ramp" was constructed using materials which "closely matched the Bay's natural beaches", including gravel, sand, ground oyster shells, and eucalyptus logs from local sources.[9] Invasive plants that had come to occupy roughly 60 percent of the island[13] were cleared;[9] they were replaced with plants selected by ecologists and seeded in plastic tubes by high school students.[4] The project, which involved moving multiple tons of material, removing large amounts of vegetation, replacing them with over 36,000 plants selected by ecologists, and taking active measures to drive away Canada geese,[14][1] was described as "letting nature take its course".[9] In 2012, the project was estimated to be completed by 2017.[4] In December 2017, volunteers from age 12 and up were still being sought to help in converting the island into a shorebird habitat.[15] In June 2020, an algae bloom "choked" miles of shoreline around Strawberry Point, and "carpeted" the shores of Aramburu Island.[16]

Animals

From the late 1960s onward, harbor seals occasionally used the island as a haul-out site, and in 1975, it served as a refuge to an estimated 30 percent of San Francisco bay's harbor seal population.[17] However, the last time a seal was seen on the island was 1985.[10] Outcomes attributed to the habitat restoration project started in 2011 included doubling the number of birds observed on the island, and causing black oystercatchers to live on the island.[9] Between April and October 2012, a cooperative report between the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Audubon Society found that there had also been black-necked stilts and killdeer raising chicks on the island.[14] The report also detailed attempts at expulsion of Canada geese from the island.[14] While previous work on the island's cliffs was unsuccessful in driving away the birds, a variety of other contraptions were used, including a grid of precisely-placed strings, and a sculpture of a coyote.[14] Unlike such removal attempts performed elsewhere, these attempts did not involve explosives or loudspeakers.[18][14]

In 2018, a joint study by the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center and the Richardson Bay Audubon Center investigated the island and surrounding Richardson Bay for the presence of Atlantic oyster drills, described as "one of the most voracious alien species in San Francisco Bay".[19] The study was part of an effort to restore Olympia oysters to the region by halting the invasive snails' "rampage" through the bay.[19]

References

- 1 2 3 "PACIFIC SOUTHWEST REGION: Aramburu Island From Dump Site to Bird Sanctuary". www.fws.gov. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ↑ "Aramburu Island". Richardson Bay Audubon Center. January 22, 2016. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- 1 2 "Aramburu Island – Marin County Parks". www.marincountyparks.org. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "An Ecological Makeover". Marin Magazine. March 19, 2012. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ↑ "All Marin Parks Now Closed Due to Large Crowds". Funcheap SF. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ↑ Santora, Lisa (2020-03-31). "ORDER OF THE HEALTH OFFICER OF THE COUNTY OF MARIN DIRECTING ALL PARKS, CAMPGROUNDS, AND OPEN SPACES TO FURTHER CLOSE MOTORIZED ACCESS" (PDF). County of Marin.

- ↑ Willis, Matt (2020-05-15). "ORDER OF THE HEALTH OFFICER OF THE COUNTY OF MARIN ALLOWING MOTORIZED ACCESS TO CERTAIN PARKS, AND OPEN SPACES, AND DIRECTING THAT OTHERS REMAIN CLOSED TO MOTORIZED ACCESS". County of Marin.

- ↑ Willis, Matt (2020-05-29). "ORDER OF THE HEALTH OFFICER OF THE COUNTY OF MARIN LIFTING ALL RESTRICTIONS ON MOTORIZED ACCESS TO PARKS AND OPEN SPACES". County of Marin.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Bay Island Gets a Facelift With a Little Help From the Tides". KQED. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- 1 2 3 Fimrite, Peter (January 2, 2012). "Richardson Bay atoll renovated as nature preserve". SFGATE. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- 1 2 "M/V Cosco Busan | Oil Spills | Damage Assessment, Remediation, and Restoration Program". darrp.noaa.gov. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Damage Assessment, Remediation, and Restoration Program. Archived from the original on December 4, 2020. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ↑ "Cosco Busan spill leads to Richardson Bay islands' revival". Marin Independent Journal. November 6, 2017. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ↑ "Rare bird turns up on restored island in Richardson Bay". The Mercury News. July 30, 2014. Archived from the original on May 3, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Aramburu Island Shoreline Protection and Ecological Enhancement: 2012 Report". California Department of Fish and Wildlife. October 31, 2012. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ↑ "Help with enhancement projects for Aramburu Island, more". Marin Independent Journal. December 15, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ↑ Lang, Gretchen (June 16, 2020). "Algae bloom turns Richardson Bay waters green". The Ark. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ↑ George, Aleta. "Restoring Aramburu Island". Bay Nature. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ↑ "GooseBuster to the Rescue: How to Get Rid of Canada Geese". Archived from the original on 2020-10-21. Retrieved 2021-03-17.

- 1 2 Fimrite, Peter (August 18, 2018). "Scientists battle alien snails in SF Bay in effort to restore native oysters". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved March 17, 2021.