Ordovician

The Ordovician is the second period of the Paleozoic era and the Phanerozoic eon. It lasted from about 485.4 million years ago (mya) to 443.4 mya.[1] It follows the Cambrian period and is followed by the Silurian period.

The Ordovician was named after the Welsh tribe of the Ordovices. It was defined by Charles Lapworth in 1879. He recognized that the fossils in the disputed strata were different from those of the Cambrian or the Silurian. Therefore, he reasoned, they should be placed in a period of their own.

Recognition of the Ordovician period was slow in Britain, but elsewhere it was quickly accepted. In 1906 it was adopted as an official period of the Paleozoic era by the International Geological Congress.

The Ordovician ended with a series of extinction events that, together amount to the second greatest extinction of the Phanerozoic. This was the End–Ordovician extinction event.

Geology

Palaeogeography

Sea levels were high during the Ordovician. Shallow (<50 metres) inland seas were the greatest for which evidence is preserved in the rocks.

During the Ordovician, the southern continents collected into a single continent called Gondwana. Gondwana started the period in equatorial latitudes and, as the period progressed, drifted toward the South Pole. Early in the Ordovician, the continents Laurentia (present-day North America), Siberia, and Baltica (present-day northern Europe) were still independent continents.

Geochemistry

The Ordovician was a time of calcite sea geochemistry in which low-magnesium calcite was the main marine precipitate of calcium carbonate.[2]

Fauna

For most of the Ordovician, life continued to flourish, but near the end of the period the End–Ordovician extinction event seriously affected planktonic forms like conodonts, graptolites, and some groups of trilobites. Brachiopods, bryozoans and echinoderms were also heavily affected, and the cone-shaped nautiloids died out completely, except for rare Silurian forms.

The extinctions may have been caused by an ice age that occurred at the end of the Ordovician period: the end of the Ordovician was one of the coldest times in the last 600 million years of earth history.

Fauna

On the whole, the fauna that emerged in the Ordovician set the scene for the rest of the Palaeozoic.[3] The fauna was dominated by suspension feeders, mainly with short food chains. The ecological system reached a new level of complexity far beyond that of the Cambrian fauna.[3]

Though less famous than the Cambrian explosion, the Ordovician featured an adaptive radiation, which was no less remarkable. Marine genera increased fourfold, resulting in 12% of all known Phanerozoic marine fauna.[4] Another change in the fauna was the strong increase in filter feeding organisms.[5] The articulate brachiopods, cephalopods, and crinoids took over. Articulate brachiopods, in particular, largely replaced trilobites in shelf communities.[6] This illustrates the greatly increased biodiversity of carbonate shell-secreting organisms in the Ordovician compared to the Cambrian.[6] Although solitary corals date back to at least the Cambrian, reef-forming corals appeared in the early Ordovician.[3]

Molluscs, which appeared during the Cambrian or even the Ediacaran, became common and varied, especially bivalves, gastropods, and nautiloid cephalopods. Now-extinct marine animals called graptolites thrived in the oceans. Some new cystoids and crinoids appeared.

It was long thought that the first true vertebrates (fish — Ostracoderms) appeared in the Ordovician, but recent discoveries in China show they probably originated in the Lower Cambrian. The very first Gnathostomata (jawed fish) appeared in the Upper Ordovician.

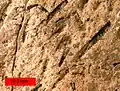

During the Middle Ordovician there was a large increase in bioeroding (shell and rock-boring) organisms. This is known as the Ordovician Bioerosion Revolution.[7] It is marked by a sudden abundance of hard substrate trace fossils.

In the Lower Ordovician, trilobites were joined by many new brachiopods, bryozoans, planktonic graptolites and conodonts, and many types of molluscs and echinoderms, including the ophiuroids ("brittle stars") and the first sea stars. Nevertheless the trilobites remained abundant, with all the Late Cambrian orders continuing, and being joined by the new group Phacopida. The first evidence of land plants also appeared.

Trilobites in the Ordovician were very different from their predecessors in the Cambrian. Many trilobites developed bizarre spines and nodules to defend against predators such as primitive sharks and nautiloids. Other trilobites evolved to become swimming forms. Some trilobites even developed shovel-like snouts for ploughing through muddy sea bottoms.[5] Some trilobites such as Asaphus kowalewski evolved long eyestalks to assist in detecting predators whereas other trilobite eyes in contrast disappeared completely.[8]

Trypanites borings in an Ordovician hardground, southeastern Indiana.[9]

Trypanites borings in an Ordovician hardground, southeastern Indiana.[9] Petroxestes borings in an Ordovician hardground, southern Ohio.[7]

Petroxestes borings in an Ordovician hardground, southern Ohio.[7]

Brachiopods and bryozoans in an Ordovician limestone, southern Minnesota.

Brachiopods and bryozoans in an Ordovician limestone, southern Minnesota. Platystrophia ponderosa, Maysvillian (Upper Ordovician) near Madison, Indiana. Scale bar is 5.0 mm.

Platystrophia ponderosa, Maysvillian (Upper Ordovician) near Madison, Indiana. Scale bar is 5.0 mm. An Ordovician strophomenid brachiopod with encrusting inarticulate brachiopods and a bryozoan.

An Ordovician strophomenid brachiopod with encrusting inarticulate brachiopods and a bryozoan. Zygospira modesta, spiriferid brachiopods, preserved in their original positions on a trepostome bryozoan; Indiana.

Zygospira modesta, spiriferid brachiopods, preserved in their original positions on a trepostome bryozoan; Indiana. Graptolites (Amplexograptus) from the Ordovician near Caney Springs, Tennessee.

Graptolites (Amplexograptus) from the Ordovician near Caney Springs, Tennessee.

Recent discovery of Burgess Shale types

The renowned Burgess Shale fauna disappears in the Middle Cambrian. It is now known that it did not go extinct, but survived, and thrived where the circumstances were right.[10] A recently discovered lagerstätte (a deposit of exceptionally preserved fossils) has been found in the Fezouata Formation, Morocco. The site contains remarkable fossils of soft-bodied animals from a muddy ocean floor. The fauna also includes some hard-bodied animals such as horseshoe crabs. Probably low oxygen conditions kept predators and scavengers to a minimum.

References

- Gradstein, Felix M; Ogg J.G. & Smith A.G. 2004. A geologic time scale 2004. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-78673-8

- Stanley, S.M.; Hardie L.A. (1999). "Hypercalcification; paleontology links plate tectonics and geochemistry to sedimentology". GSA Today. 9: 1–7.

- Munnecke A. et al 2010. Ordovician and Silurian sea-water chemistry, sea level, and climate: a synopsis. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 296, 389-413. Early Palaeozoic sea level and climate - selected papers presented at the IGCP 503 closing meeting in Lille (France), 23-31 August 2008

- Dixon, Dougal; et al. (2001). Atlas of life on Earth. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. p. 87. ISBN 0760719578.

- "Palaeos Paleozoic : Ordovician : The Ordovician Period". Archived from the original on 2007-12-21. Retrieved 2010-10-01.

- Cooper, John D.; Miller, Richard H. and Patterson, Jacqueline (1986). A trip through time: principles of historical geology. Columbus: Merrill Publishing Company. pp. 247, 255–259. ISBN 0675201403.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wilson, M.A.; Palmer T.J. (2006). "Patterns and processes in the Ordovician Bioerosion Revolution" (PDF). Ichnos. 13 (3): 109–112. doi:10.1080/10420940600850505. S2CID 128831144. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-16.

- A Guide to the Orders of Trilobites

- Wilson, M.A.; Palmer T.J. (2001). "Domiciles, not predatory borings: a simpler explanation of the holes in Ordovician shells analyzed by Kaplan and Baumiller, 2000". PALAIOS. 16 (5): 524–525. Bibcode:2001Palai..16..524W. doi:10.1669/0883-1351(2001)016<0524:DNPBAS>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 130036115.

- Van Roy, Peter 2010. Ordovician faunas of Burgess Shale type. Nature 465, 215-218.