DNA

DNA, short for deoxyribonucleic acid, is the molecule that contains the genetic code of organisms. This includes animals, plants, protists, archaea and bacteria. It is made up of two polynucleotide chains in a double helix.[1]

DNA is in each cell in the organism and tells cells what proteins to make. Mostly, these proteins are enzymes. DNA is inherited by children from their parents. This is why children share traits with their parents, such as skin, hair and eye color. The DNA in a person is a combination of the DNA from each of their parents.

Part of an organism's DNA is "non-coding DNA" sequences. They do not code for protein sequences. Some noncoding DNA is transcribed into non-coding RNA molecules, such as transfer RNA, ribosomal RNA, and regulatory RNAs.[2] Other sequences are not transcribed at all, or give rise to RNA of unknown function. The amount of non-coding DNA varies greatly among species. For example, over 98% of the human genome is non-coding DNA,[3] while only about 2% of a typical bacterial genome is non-coding DNA.

Viruses use either DNA or RNA to infect organisms.[4] The genome replication of most DNA viruses takes place in the cell's nucleus, whereas RNA viruses usually replicate in the cytoplasm.

Inside eukaryotic cells, DNA is organized into chromosomes. Before cell division, more chromosomes are made in the process of DNA replication. Eukaryotic organisms like animals, plants, fungi and protists store most of their DNA inside the cell nucleus. But prokaryotes, like bacteria and archaea store their DNA only in the cytoplasm, in circular chromosomes. Inside eukaryotic chromosomes, chromatin proteins, such as histones, help to compact and organize DNA.[5]

Structure of DNA

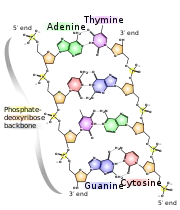

DNA has a double helix shape, which is like a ladder twisted into a spiral. Each step of the ladder is a pair of nucleotides.

Nucleotides

A nucleotide is a molecule made up of:

- deoxyribose, a kind of sugar with 5 carbon atoms,

- a phosphate group made of phosphorus and oxygen, and

- nitrogenous base

DNA is made of four types of nucleotide:

The 'rungs' of the DNA ladder are each made of two bases, one base coming from each leg. The bases connect in the middle: 'A' only pairs with 'T', and 'C' only pairs with 'G'. The bases are held together by hydrogen bonds.

Adenine (A) and thymine (T) can pair up because they make two hydrogen bonds, and cytosine (C) and guanine (G) pair up to make three hydrogen bonds. Although the bases are always in fixed pairs, the pairs can come in any order (A-T or T-A; similarly, C-G or G-C). This way, DNA can write 'codes' out of the 'letters' that are the bases. These codes contain the message that tells the cell what to do.

Chromatin

On chromosomes, the DNA is bound up with proteins called histones to form chromatin. This association takes part in epigenetics and gene regulation. Genes are switched on and off during development and cell activity, and this regulation is the basis of most of the activity which takes place in cells.

Copying DNA

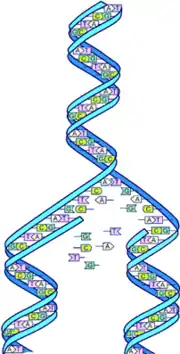

When DNA is copied, this is called DNA replication. Briefly, the hydrogen bonds holding together paired bases are broken and the molecule is split in half: the legs of the ladder are separated. This gives two single strands. New strands are formed by matching the bases (A with T and G with C) to make the missing strands.

First, an enzyme called DNA helicase splits the DNA down the middle by breaking the hydrogen bonds. Then after the DNA molecule is in two separate pieces, another molecule called DNA polymerase makes a new strand that matches each of the strands of the split DNA molecule. Each copy of a DNA molecule is made of half of the original (starting) molecule and half of new bases.

Mutations

When DNA is copied, mistakes are sometimes made – these are called mutations. There are four main types of mutations:

- Deletion, where one or more bases are left out.

- Substitution, where one or more bases are substituted for another base in the sequence.

- Insertion, where one or more extra base is put in.

- Duplication, where a sequence of bases pairs are repeated.

Mutations may also be classified by their effect on the structure and function of proteins, or their effect on fitness. Mutations may be bad for the organism, or neutral, or of benefit. Sometimes mutations are fatal for the organism – the protein made by the new DNA does not work at all, and this causes the embryo to die. On the other hand, evolution is moved forward by mutations, when the new version of the protein works better for the organism.

Protein synthesis

A section of DNA that contains instructions to make a protein is called a gene. Each gene has the sequence for at least one polypeptide.[6] Proteins form structures, and also form enzymes. The enzymes do most of the work in cells. Proteins are made out of smaller polypeptides, which are formed of amino acids. To make a protein to do a particular job, the correct amino acids need to be joined up in the correct order.

Proteins are made by tiny machines in the cell called ribosomes. Ribosomes are in the main body of the cell, but DNA is only in the nucleus of the cell. The codon is part of the DNA, but DNA never leaves the nucleus. Because DNA cannot leave the nucleus, the cell nucleus makes a copy of the DNA sequence in RNA. This is smaller and can get through the holes – pores – in the membrane of the nucleus and out into the cell.

Genes encoded in DNA are transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA) by proteins such as RNA polymerase. Mature mRNA is then used as a template for protein synthesis by the ribosome. Ribosomes read codons, 'words' made of three base pairs that tell the ribosome which amino acid to add. The ribosome scans along an mRNA, reading the code while it makes protein. Another RNA called tRNA helps match the right amino acid to each codon.[7]

History of DNA research

DNA was first isolated (extracted from cells) by Swiss physician Friedrich Miescher in 1869, when he was working on bacteria from the pus in surgical bandages. The molecule was found in the nucleus of the cells and so he called it nuclein.[8]

In 1928, Frederick Griffith discovered that traits of the "smooth" form of Pneumococcus could be transferred to the "rough" form of the same bacteria by mixing killed "smooth" bacteria with the live "rough" form.[9] This system provided the first clear suggestion that DNA carries genetic information.

The Avery–MacLeod–McCarty experiment identified DNA as the transforming principle in 1943.[10][11]

DNA's role in heredity was confirmed in 1952, when Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase in the Hershey–Chase experiment showed that DNA is the genetic material of the T2 bacteriophage.[12]

In the 1950s, Erwin Chargaff [13] found that the amount of thymine (T) present in a molecule of DNA was about equal to the amount of adenine (A) present. He found that the same applies to guanine (G) and cytosine (C). Chargaff's rules summarises this finding.

In 1953, James D. Watson and Francis Crick suggested what is now accepted as the first correct double-helix model of DNA structure in the journal Nature.[14] Their double-helix, molecular model of DNA was then based on a single X-ray diffraction image "Photo 51", taken by Rosalind Franklin and Raymond Gosling in May 1952.[15]

Experimental evidence supporting the Watson and Crick model was published in a series of five articles in the same issue of Nature.[16] Of these, Franklin and Gosling's paper was the first publication of their own X-ray diffraction data and original analysis method that partly supported the Watson and Crick model;[17] this issue also contained an article on DNA structure by Maurice Wilkins and two of his colleagues, whose analysis and in vivo B-DNA X-ray patterns also supported the presence in vivo of the double-helical DNA configurations as proposed by Crick and Watson for their double-helix molecular model of DNA in the previous two pages of Nature. In 1962, after Franklin's death, Watson, Crick, and Wilkins jointly received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.[18] Nobel Prizes are awarded only to living recipients. A debate continues about who should receive credit for the discovery.[19]

In 1957, Crick explained the relationship between DNA, RNA, and proteins, in the central dogma of molecular biology.[20]

How DNA was copied (the replication mechanism) came in 1958 through the Meselson–Stahl experiment.[21] More work by Crick and coworkers showed that the genetic code was based on non-overlapping triplets of bases, called codons.[22] These findings represent the birth of molecular biology.

How Watson and Crick got Franklin's results has been much debated. Crick, Watson and Maurice Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1962 for their work on DNA – Rosalind Franklin had died in 1958.

What happens when DNA gets damaged

DNA gets damaged a lot of times in cells which is a problem has DNA provide instructions to making proteins. But, cells have ways to fix these problems most of the time. Cells make use of special enzymes.[5] Different enzymes fix different types of damages to DNA. The problem comes in different types:

- One common error is base mismatch or where the bases are not matched correctly. This is where maybe for example, adenine is not matched with thymine or Guanine is not matched with cytosine. When a cell copies its own DNA a special enzyme called polymerase matches the bases together. But once in a while, there is an error. Usually, the enzyme notices it and fixes it, but just make sure, another set of proteins check what the enzyme has done. If the proteins find a base that was not matched with the right base, they remove it and replace it with a nucleotide with the right base.[23]

- DNA can also be broken chemically by certain compounds. This can be toxic compounds like those found in tobacco or compounds the cell meets every day like hydrogen peroxide. Some chemical damages by compounds happens so much that there is a special enzyme to fix those types of problems.[23][24]

- When a base gets damaged, it is usually fixed in a process called base excision repair. Here, an enzyme removes the base and another group of enzymes trim around the damage and replaces it with a new nucleotide.[5]

- UV light damages DNA in such a way that it changes its shape. Fixing this type of damage takes a more complex process called nucleotide excision repair. Here, a team of proteins remove a long strand of 20 or more broken nucleotides and replaces them with fresh new ones.[24]

- High energy waves like x-rays and gamma rays can actually cut one or both strands of DNA. This type of damage is called a double strand break. One double strand break can cause the cell to die. Two common ways the cell fixes this problem is homologous recombination and non homologous end joining. In homologous recombination, enzymes use a similar part of another gene as a template to fix the break. In non-homologous end joining enzymes trim around the place where the DNA strand broke and put them together. This way is much less accurate but works when there is no similar genes available.[23]

DNA and privacy concerns

Police in the United States used DNA and family tree public databases to solve cold cases. The American Civil Liberties Union raised concerns over this practice.[25]

Related pages

References

- "Definition of DEOXYRIBONUCLEIC ACID". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- Alberts, Bruce (2015). Molecular biology of the cell (Sixth ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 978-0-8153-4432-2. OCLC 887605755.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Elgar G. & Vavouri T. 2008. Tuning in to the signals: non-coding sequence conservation in vertebrate genomes. Trends Genet. 24 (7): 344–52. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2008.04.005

- Van Etten JL, Lane LC, Dunigan DD (2010). "DNA viruses: the really big ones (giruses)". Annual Review of Microbiology. 64: 83–99. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134338. PMC 2936810. PMID 20690825.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Alberts, Bruce (2002). Molecular biology of the cell. Alexander Johnson, Julian Lewis, Martin Raff, Keith Roberts, Peter Walter (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3218-1. OCLC 48122761.

- Many complex proteins consist of more than one polypeptide, and the polypeptides are coded separately. They are brought together at a later stage: see RNA splicing.

- Plomin R. 2018. How DNA makes us who we are. London, Penguin. ISBN 978-0-241-36769-8

- Dahm R (2005). "Friedrich Miescher and the discovery of DNA". Dev Biol. 278 (2): 274–88. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.11.028. PMID 15680349.

- Lorenz MG, Wackernagel W (1994). "Bacterial gene transfer by natural genetic transformation in the environment". Microbiol. Rev. 58 (3): 563–602. doi:10.1128/mr.58.3.563-602.1994. PMC 372978. PMID 7968924.

- Avery, O. T.; MacLeod, C. M.; McCarty, M. (1944-02-01). "Studies on the chemical nature of the substance inducing transformation of pneumococcal types: induction of transformation by a Desoxyribonucleic Acid fraction isolated from Pneumococcus Type III". Journal of Experimental Medicine. 79 (2): 137–158. doi:10.1084/jem.79.2.137. PMC 2135445. PMID 19871359. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- Fruton, Joseph S. 1999. Proteins, enzymes, genes: the interplay of chemistry and biology. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press. 438–440 ISBN 0-300-07608-8

- Hershey A.D. and Chase M. 1952. Independent functions of viral protein and nucleic acid in growth of bacteriophage. J Gen Physiol. 36:39-56

- Vischer E. and Chargaff E. (1948). "The separation and quantitative estimation of purines and pyrimidines in minute amounts". J. Biol. Chem. 176 (2): 703–714. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)52686-2. PMID 18889926.

- Watson J.D. & Crick F.H.C. (1953). "A structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid". Nature. 171 (4356): 737–738. doi:10.1038/171737a0. PMID 13054692. S2CID 4253007.

- Franklin R.E. & Gosling R.G. (1953). "Molecular configuration in sodium thymonucleate". Nature. 171 (4356): 740–741. Bibcode:1953Natur.171..740F. doi:10.1038/171740a0. PMID 13054694. S2CID 4268222.

- Nature Archives Double Helix of DNA: 50 Years

- "Original X-ray diffraction image". Osulibrary.oregonstate.edu. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1962 Nobelprize .org Accessed 22 December 06

- Brenda Maddox (23 January 2003). "The double helix and the 'wronged heroine'" (PDF). Nature. 421 (6921): 407–408. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..407M. doi:10.1038/nature01399. PMID 12540909. S2CID 4428347. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- Crick F.H.C. On degenerate templates and the adaptor hypothesis (PDF). Archived 2008-10-01 at the Wayback Machine genome.wellcome.ac.uk (Lecture, 1955). Retrieved 22 December 2006.

- Meselson M. and Stahl F.W. 1958. The Replication of DNA in Escherichia coli. PNAS 44: 671–82

- The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1968 Nobelprize.org Accessed 22 December 06

- Hoeijmakers, Jan H.J. (2009-10-08). "DNA Damage, Aging, and Cancer". New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (15): 1475–1485. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0804615. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 19812404.

- Douki, Thierry; Reynaud-Angelin, Anne; Cadet, Jean; Sage, Evelyne (2003-08-01). "Bipyrimidine Photoproducts Rather than Oxidative Lesions Are the Main Type of DNA Damage Involved in the Genotoxic Effect of Solar UVA Radiation". Biochemistry. 42 (30): 9221–9226. doi:10.1021/bi034593c. ISSN 0006-2960. PMID 12885257.

- "DNA, family tree help solve 52-year-old Seattle murder case". Fox News. 7 May 2019.