Bacteriophage

A bacteriophage is a virus that infects bacteria. The term is commonly shortened to phage. Bacteriophages are among the most common and diverse entities in the biosphere.[1] Like viruses that infect eukaryotes (plants, animals, and fungi) there are many different phage structures and functions.[2]

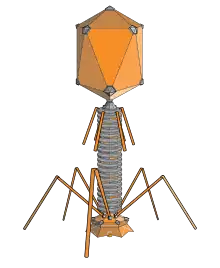

The top of phages is made up of a dice-like shape which has 20 sides and 30 edges. Inside it contains the genetic information, which is its DNA. This dice-like shape often sits on a tail that has leg-like fibres.

Phages are typically made of an outer protein hull that has genetic material inside it. The genetic material may be single-stranded (ssRNA or ssDNA), or double-stranded (dsRNA or dsDNA). It may be between 5,000 and 500,000 base pairs long with either circular or linear arrangement. Bacteriophages are usually between 20 and 200 nanometers in size.

Phage genomes may code for as few as four genes,[3] and as many as hundreds of genes. Phages have a life cycle that begins when the phage attaches to the bacterium. Then they inject their genome into the bacterium. The genome uses the parts of the bacterium to replicate inside it. When there are many phages inside the bacterium, they put enzymes in the bacterium that weaken the outer cell wall so they can burst through it to infect new bacterias.

Phages are everywhere there are bacteria, such as soils or the intestines of animals. They are very common in sea water: up to 9×108 virions per milliliter have been found in microbial mats at the surface,[4] and up to 70% of marine bacteria may be infected by phages.[5]

They have been used for over 90 years as an alternative to antibiotics in the former Soviet Union and Central Europe, as well as in France.[6] However, it was not until the first phage was observed under an electron microscope by Helmut Ruska in 1939 that its true nature was established.[7]

They are a possible therapy against antibiotic resistant strains of many bacteria.[8] On the other hand, some phages complicate biofilms involved in pneumonia and cystic fibrosis. They shelter the bacteria from drugs and so prolong the infection.[9]

References

- Grath, Stephen Mc; Sinderen, Douwe van (2007). Bacteriophage: genetics and molecular biology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-14-1. Bacteriophage: Genetics and Molecular Biology.

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "bacteriophage". Encyclopedia Britannica, Invalid Date, https://www.britannica.com/science/bacteriophage. Accessed 25 December 2021.

- Bacteriophage MS2

- Wommack K.E. & Colwell R.R. 2000 (2000). "Virioplankton: viruses in aquatic ecosystems". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 64 (1): 69–114. doi:10.1128/MMBR.64.1.69-114.2000. PMC 98987. PMID 10704475.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Prescott, Lansing M.; Harley, John P.; Klein, Donald A. (1993). Microbiology. Wm. C. Brown. ISBN 978-0-697-01372-9.

- BBC Horizon 1997. The virus that cures – a documentary about the history of phage medicine in Russia and the West

- Ackermann H-W. 2009. History of Virology: Bacteriophages. Desk Encyclopedia of General Virology. pp. 3–5.

- Keen E.C. 2012 (2012). "Phage therapy: concept to cure". Frontiers in Microbiology. 3: 238. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00238. PMC 3400130. PMID 22833738.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Bacteria and bacteriophages collude in the formation of clinically frustrating biofilms