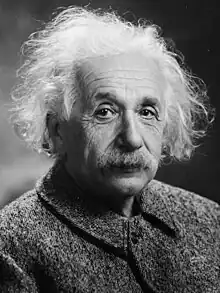

Albert Einstein

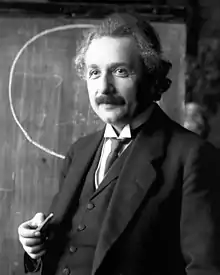

Albert Einstein (14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born American Jewish scientist.[5] He worked on theoretical physics.[6] He developed the theory of relativity.[4][7] He won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921 for theoretical physics.

Albert Einstein | |

|---|---|

Einstein in 1921 | |

| Born | 14 March 1879 |

| Died | 18 April 1955 (aged 76) Princeton, New Jersey, United States |

| Citizenship |

|

| Education |

|

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Lieserl Einstein Hans Albert Einstein Eduard "Tete" Einstein |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics, philosophy |

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | Eine neue Bestimmung der Moleküldimensionen (A New Determination of Molecular Dimensions) (1905) |

| Doctoral advisor | Alfred Kleiner |

| Other academic advisors | Heinrich Friedrich Weber |

| Influences |

|

| Influenced |

|

| Signature | |

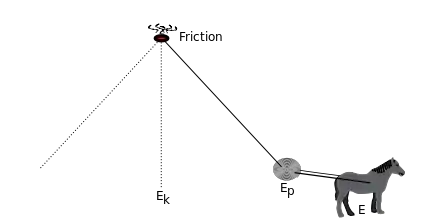

His most famous equation is in which E is for Energy, m for mass, c is the speed of light is therefore Energy equals mass multiplied by the speed of light squared.

At the start of his career, Einstein didn't think that Newtonian mechanics was enough to bring together the laws of classical mechanics and the laws of the electromagnetic field. Between 1902 and 1909 he made the theory of special relativity to fix it.

Einstein also thought that Isaac Newton's idea of gravity was not completely correct. So, he extended his ideas on special relativity to include gravity. In 1916, he published a paper on general relativity with his theory of gravitation.

In 1933, Einstein was visiting the United States but in Germany, Adolf Hitler and the Nazis came to power (this is before World War II). Since Einstein was Jewish, he did not go back to Germany because of Hitler’s anti-Semitic laws.[8] He lived in the United States and became an American citizen in 1940.[9] On the beginning of World War II, he and Leó Szilárd sent a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt explaining to him that Germany was in the making an Atomic bomb; so Einstein and Szilard recommended that the U.S. should also make one. This led to the Manhattan Project, and the U.S. became the first nation in history to create and use the atomic bomb (not on Germany but on Japan). Einstein and other physicists like Richard Feynman who worked on the Manhattan Project later regretted that the bomb was used on Japan.[10]

Einstein lived in Princeton and was one of the first members invited to the Institute for Advanced Study, where he worked for the rest of his life.

He is now thought to be one of the greatest scientists of all time.

His contributions helped lay the foundations for all modern branches of physics, including quantum mechanics and relativity.

Life

Early life

Einstein was born in Ulm, Württemberg, Germany, on 14 March 1879.[11] His family was Jewish, but was not very religious. However, later in life Einstein became very interested in his Judaism. Einstein did not begin speaking until he was 4 years old. According to his younger sister, Maja, "He had such difficulty with language that those around him feared he would never learn".[12] When Einstein was around 4 years old, his father gave him a magnetic compass. He tried hard to understand how the needle could seem to move itself so that it always pointed north. The needle was in a closed case, so clearly nothing like wind could be pushing the needle around, and yet it moved. So in this way Einstein became interested in studying science and mathematics. His compass gave him ideas to explore the world of science.

When he became older, he went to school in Switzerland. After he graduated, he got a job in the patent office there. While he was working there, he wrote the papers that first made him famous as a great scientist.

Einstein married with a 20-year-old Serbian woman Mileva Marić in January 1903.

In 1917, Einstein became very sick with an illness that almost killed him, fortunately he survived. His cousin Elsa Löwenthal nursed him back to health. After this happened, Einstein divorced Mileva on 14 February 1919, and married Elsa on 2 June 1919.

Children

Einstein's first daughter was Lieserl Einstein. She was born in Novi Sad, Vojvodina, Austria-Hungary on January 27, 1902. She spent her first years in the care of Serbian grandparents because her father Albert did not want her to be brought to Switzerland, where he had a job offer at the patent office. Some historians believe she died from scarlet fever.[13]

Einstein's two sons were Hans Albert Einstein and Eduard Tete Einstein. Hans Albert was born in Bern, Switzerland in May 1904. He became a professor in Berkeley (California). Eduard was born in Zürich, Switzerland in July 1910. He died at 55 years old of a stroke in the Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich "Burghölzli" . He had spent his life in and out of hospitals due to his schizophrenia.

Later life

In spring of 1914, he moved back to Germany, and became ordinary member of the Prussian Academy and director of a newly established institute for physics of the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft. He lived in Berlin and finished the General Theory of Relativity in November 1915. In the Weimar Republic, he was politically active for socialism and Zionism. In 1922, he received the Nobel prize for Physics for his explanation of the photoelectric effect in 1905. He then tried to formulate a general field theory uniting gravitation and electromagnetism, without success. He had reservations about the quantum mechanics invented by Heisenberg (1925) and Schrödinger (1926). In spring of 1933, Einstein and Elsa were traveling in the US when the Nazi party came to power. The Nazis were violently antisemitic. They called Einstein's relativity theory "Jewish physics," and some German physicists started polemics against his theories. Others, like Planck and Heisenberg, defended Einstein.

After their return to Belgium, considering the threats from the Nazis, Einstein resigned from his position in the Prussian Academy in a letter from Oostende. Einstein and Elsa decided not to go back to Berlin and moved to Princeton, New Jersey in the United States, and in 1940 he became a United States citizen.

Before World War II, in August 1939, Einstein at the suggestion of Leó Szilárd wrote to the U.S. president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, to say that the United States should invent an atomic bomb so that the Nazi government could not beat them to the punch. He signed the letter. However, he was not part of the Manhattan Project, which was the project that created the atomic bomb.[14]

Einstein, a Jew but not an Israeli citizen, was offered the presidency in 1952 but turned it down, stating "I am deeply moved by the offer from our State of Israel, and at once saddened and ashamed that I cannot accept it."[15] Ehud Olmert was reported to be considering offering the presidency to another non-Israeli, Elie Wiesel, but he was said to be "very not interested".[16]

He did his research on gravitation at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, New Jersey until his death on 18 April 1955 of a burst aortic aneurysm. He was still writing about quantum physics hours before he died. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics.

Photoelectric effect

In 1905 he came up with a theory that light was made of small particles called photons ^ . Using this theory he was able to explain the photoelectric effect. The formula relating the energy and frequency of a photon is . This means that higher frequency light has more energy per photon.

The photoelectric effect happens when light shining on a metal surface causes it to emit electrons. The difficulty for the classical wave theory was to explain why this effect only seems to occur for high frequency light such as UV, but not lower frequency such as red or infrared. Einstein showed that, since higher frequency light has photons with more energy, it has a greater chance of forcing electrons out of the metal.

Einstein was also able to explain other phenomena with photons, such as fluorescence and ionization. In 1921 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for this discovery.

Theory of relativity

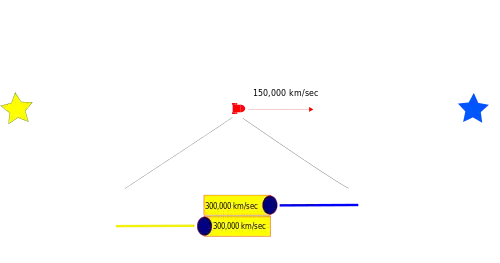

The theory of special relativity was published by Einstein in 1905, in the paper On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies.[17] It says that both distance measurements and time measurements change near the speed of light. This means that as one get closer to the speed of light (nearly 300,000 kilometres per second), lengths appear to get shorter, and clocks tick more slowly. Einstein said that special relativity is based on two ideas. The first is that the laws of physics are the same for all observers that are not moving in relation to each other.

Things going in the same direction at the same speed are said to be in an inertial frame.

People in the same "frame" measure how long something takes to happen. Their clocks keep the same time. But in another "frame" their clocks move at a different rate. The reason this happens is as follows. No matter how an observer is moving, if he measures the speed of the light coming from that star it will always be the same number.

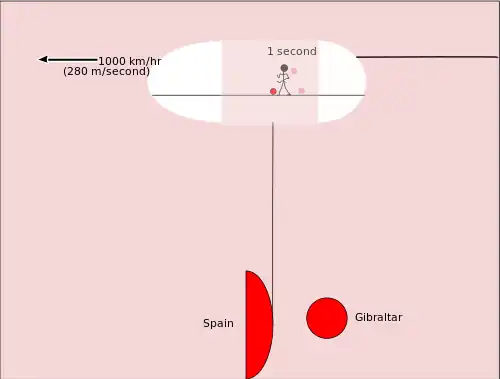

Imagine an astronaut were all alone in a different universe. It just has an astronaut and a spaceship. Is he moving? Is he standing still? Those questions do not mean anything. Why? Because when we say we are moving we mean that we can measure our distance from something else at various times. If the numbers get bigger we are moving away. If the numbers get smaller we are moving closer. To have movement you must have at least two things. An airplane can be moving at several hundred kilometers per hour, but passengers say, "I am just sitting here."

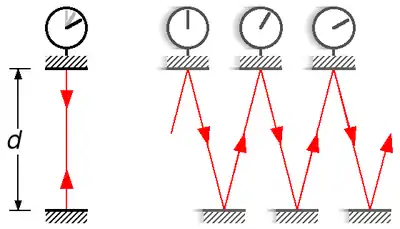

Suppose some people are on a spaceship and they want to make an accurate clock. At one end they put a mirror, and at the other end they put a simple machine. It shoots one short burst of light toward the mirror and then waits. The light hits the mirror and bounces back. When it hits a light detector on the machine, the machine says, "Count = 1," it simultaneously shoots another short burst of light toward the mirror, and when that light comes back the machine says, "Count = 2." They decide that a certain number of bounces will be defined as a second, and they make the machine change the seconds counter every time it has detected that number of bounces. Every time it changes the seconds counter it also flashes a light out through a porthole under the machine. So somebody outside can see the light flashing every second.

Every grade school child learns the formula d=rt (distance equals rate multiplied by time). We know the speed of light, and we can easily measure the distance between the machine and the mirror and multiple that to give the distance the light travels. So we have both d and r, and we can easily calculate t. The people on the spaceship compare their new "light clock" with their various wrist watches and other clocks, and they are satisfied that they can measure time well using their new light clock.

Now this spaceship happens to be going very fast. They see a flash from the clock on the space ship, and then they see another flash. Only the flashes do not come a second apart. They come at a slower rate. Light always goes at the same speed, d = rt. That is why the clock on the spaceship is not flashing once a second for the outside observer.

Special relativity also relates energy with mass, in Albert Einstein's E=mc2 formula.

Mass-energy equivalence

E=mc2, also called the mass-energy equivalence, is one of the things that Einstein is most famous for. It is a famous equation in physics and math that shows what happens when mass changes to energy or energy changes to mass. The "E" in the equation stands for energy. Energy is a number which you give to objects depending on how much they can change other things. For instance, a brick hanging over an egg can put enough energy onto the egg to break it, but a feather can not.

There are three basic forms of energy: potential energy, kinetic energy, and rest energy. Two of these forms of energy can be seen in the examples given above, and in the example of a pendulum.

A cannonball hangs on a rope from an iron ring. A horse pulls the cannonball to the right side. When the cannonball is released it will move back and forth as diagrammed. It would do that forever except that the movement of the rope in the ring and rubbing in other places causes friction, and the friction takes away a little energy all the time. If we ignore the losses due to friction, then the energy provided by the horse is given to the cannonball as potential energy. (It has energy because it is up high and can fall down.) As the cannonball swings down it gains more and more speed, so the nearer the bottom it gets the faster it is going and the harder it would hit you if you stood in front of it. Then it slows down as its kinetic energy is changed back into potential energy. "Kinetic energy" just means the energy something has because it is moving. "Potential energy" just means the energy something has because it is in some higher position than something else.

When energy moves from one form to another, the amount of energy always remains the same. It cannot be made or destroyed. This rule is called the "conservation law of energy". For example, when you throw a ball, the energy is transferred from your hand to the ball as you release it. But the energy that was in your hand, and now the energy that is in the ball, is the same number. For a long time, people thought that the conservation of energy was all there was to talk about.

When energy transforms into mass, the amount of energy does not remain the same. When mass transforms into energy, the amount of energy also does not remain the same. However, the amount of matter and energy remains the same. Energy turns into mass and mass turns into energy in a way that is defined by Einstein's equation, E = mc2.

.png.webp)

The "m" in Einstein's equation stands for mass. Mass is the amount of matter there is in some body. If you knew the number of protons and neutrons in a piece of matter such as a brick, then you could calculate its total mass as the sum of the masses of all the protons and of all the neutrons. (Electrons are so small that they are almost negligible.) Masses pull on each other, and a very large mass such as that of the Earth pulls very hard on things nearby. You would weigh much more on Jupiter than on Earth because Jupiter is so huge. You would weigh much less on the Moon because it is only about one-sixth the mass of Earth. Weight is related to the mass of the brick (or the person) and the mass of whatever is pulling it down on a spring scale – which may be smaller than the smallest moon in the solar system or larger than the Sun.

Mass, not weight, can be transformed into energy. Another way of expressing this idea is to say that matter can be transformed into energy. Units of mass are used to measure the amount of matter in something. The mass or the amount of matter in something determines how much energy that thing could be changed into.

Energy can also be transformed into mass. If you were pushing a baby buggy at a slow walk and found it easy to push, but pushed it at a fast walk and found it harder to move, then you would wonder what was wrong with the baby buggy. Then if you tried to run and found that moving the buggy at any faster speed was like pushing against a brick wall, you would be very surprised. The truth is that when something is moved then its mass is increased. Human beings ordinarily do not notice this increase in mass because at the speed humans ordinarily move the increase in mass is almost nothing.

As speeds get closer to the speed of light, then the changes in mass become impossible not to notice. The basic experience we all share in daily life is that the harder we push something like a car the faster we can get it going. But when something we are pushing is already going at some large part of the speed of light we find that it keeps gaining mass, so it gets harder and harder to get it going faster. It is impossible to make any mass go at the speed of light because to do so would take infinite energy.

Sometimes a mass will change to energy. Common examples of elements that make these changes we call radioactivity are radium and uranium. An atom of uranium can lose an alpha particle (the atomic nucleus of helium) and become a new element with a lighter nucleus. Then that atom will emit two electrons, but it will not be stable yet. It will emit a series of alpha particles and electrons until it finally becomes the element Pb or what we call lead. By throwing out all these particles that have mass it has made its own mass smaller. It has also produced energy.[18]

In most radioactivity, the entire mass of something does not get changed to energy. In an atomic bomb, uranium is transformed into krypton and barium. There is a slight difference in the mass of the resulting krypton and barium, and the mass of the original uranium, but the energy that is released by the change is huge. One way to express this idea is to write Einstein's equation as:

E = (muranium – mkrypton and barium) c2

The c2 in the equation stands for the speed of light squared. To square something means to multiply it by itself, so if you were to square the speed of light, it would be 299,792,458 meters per second, times 299,792,458 meters per second, which is approximately

(3•108)2 =

(9•1016 meters2)/seconds2=

90,000,000,000,000,000 meters2/seconds2

So the energy produced by one kilogram would be:

E = 1 kg • 90,000,000,000,000,000 meters2/seconds2

E = 90,000,000,000,000,000 kg meters2/seconds2

or

E = 90,000,000,000,000,000 joules

or

E = 90,000 terajoule

About 60 terajoules were released by the atomic bomb that exploded over Hiroshima.[19] So about two-thirds of a gram of the radioactive mass in that atomic bomb must have been lost (changed into energy), when the uranium changed into krypton and barium.

BEC

The idea of a Bose-Einstein condensate came out of a collaboration between S. N. Bose and Prof. Einstein. Einstein himself did not invent it but, instead, refined the idea and helped it become popular.

Zero-point energy

The concept of zero-point energy was developed in Germany by Albert Einstein and Otto Stern in 1913.

Momentum, mass, and energy

In classical physics, momentum is explained by the equation:

- p = mv

where

- p represents momentum

- m represents mass

- v represents velocity (speed)

When Einstein generalized classical physics to include the increase of mass due to the velocity of the moving matter, he arrived at an equation that predicted energy to be made of two components. One component involves "rest mass" and the other component involves momentum, but momentum is not defined in the classical way. The equation typically has values greater than zero for both components:

- E2 = (m0c2)2 + (pc)2

where

- E represents the energy of a particle

- m0 represents the mass of the particle when it is not moving

- p represents the momentum of the particle when it is moving

- c represents the speed of light.

There are two special cases of this equation.

A photon has no rest mass, but it has momentum. (Light reflecting from a mirror pushes the mirror with a force that can be measured.) In the case of a photon, because its m0 = 0, then:

- E2 = 0 + (pc)2

- E = pc

- p = E/c

The energy of a photon can be computed from its frequency ν or wavelength λ. These are related to each other by Planck's relation, E = hν = hc/λ, where h is the Planck constant (6.626×10−34 joule-seconds). Knowing either frequency or wavelength, you can compute the photon's momentum.

In the case of motionless particles with mass, since p = 0, then:

- E02 = (m0c2)2 + 0

which is just

- E0 = m0c2

Therefore, the quantity "m0" used in Einstein's equation is sometimes called the "rest mass." (The "0" reminds us that we are talking about the energy and mass when the speed is 0.) This famous "mass-energy relation" formula (usually written without the "0"s) suggests that mass has a large amount of energy, so maybe we could convert some mass to a more useful form of energy. The nuclear power industry is based on that idea.

Einstein said that it was not a good idea to use the classical formula relating momentum to velocity, p = mv, but that if someone wanted to do that, he would have to use a particle mass m that changes with speed:

- mv2 = m02 / (1 – v2/c2)

In this case, we can say that E = mc2 is also true for moving particles.

The General Theory of Relativity

| Part of a series of articles about |

| General relativity |

|---|

|

|

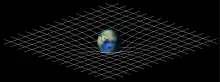

The General Theory of Relativity was published in 1915, ten years after the special theory of relativity was created. Einstein's general theory of relativity uses the idea of spacetime. Spacetime is the fact that we have a four-dimensional universe, having three spatial (space) dimensions and one temporal (time) dimension. Any physical event happens at some place inside these three space dimensions, and at some moment in time. According to the general theory of relativity, any mass causes spacetime to curve, and any other mass follows these curves. Bigger mass causes more curving. This was a new way to explain gravitation (gravity).

General relativity explains gravitational lensing, which is light bending when it comes near a massive object. This explanation was proven correct during a solar eclipse, when the sun's bending of starlight from distant stars could be measured because of the darkness of the eclipse.

General relativity also set the stage for cosmology (theories of the structure of our universe at large distances and over long times). Einstein thought that the universe may curve a little bit in both space and time, so that the universe always had existed and always will exist, and so that if an object moved through the universe without bumping into anything, it would return to its starting place, from the other direction, after a very long time. He even changed his equations to include a "cosmological constant," in order to allow a mathematical model of an unchanging universe. The general theory of relativity also allows the universe to spread out (grow larger and less dense) forever, and most scientists think that astronomy has proved that this is what happens. When Einstein realized that good models of the universe were possible even without the cosmological constant, he called his use of the cosmological constant his "biggest blunder," and that constant is often left out of the theory. However, many scientists now believe that the cosmological constant is needed to fit in all that we now know about the universe.

A popular theory of cosmology is called the Big Bang. According to the Big Bang theory, the universe was formed 15 billion years ago, in what is called a "gravitational singularity". This singularity was small, dense, and very hot. According to this theory, all of the matter that we know today came out of this point.

Einstein himself did not have the idea of a "black hole", but later scientists used this name for an object in the universe that bends spacetime so much that not even light can escape it. They think that these ultra-dense objects are formed when giant stars, at least three times the size of our sun, die. This event can follow what is called a supernova. The formation of black holes may be a major source of gravitational waves, so the search for proof of gravitational waves has become an important scientific pursuit.

Beliefs

Many scientists only care about their work, but Einstein also spoke and wrote often about politics and world peace. He liked the ideas of socialism and of having only one government for the whole world. He also worked for Zionism, the effort to try to create the new country of Israel.

In his final days, Einstein faced a crucial decision. Doctors offered surgery to treat his condition, but he chose a different path. He believed in living life naturally, saying, “I want to go when I want to go. It is tasteless to prolong life artificially.” With these words, Einstein showed us the dignity in accepting life’s natural cycle.[20] On January 3, 1954, Einstein sent the following reply to Gutkind: "The word God is for me nothing more than the expression and product of human weaknesses, the Bible a collection of honourable, but still primitive legends which are nevertheless pretty childish. .... For me the Jewish religion like all other religions is an incarnation of the most childish superstitions."[21][22][23] In 2018 his letter to Gutkind was sold for $2.9 million.[24]

Even though Einstein thought of many ideas that helped scientists understand the world much better, he disagreed with some scientific theories that other scientists liked. The theory of quantum mechanics discusses things that can happen only with certain probabilities, which cannot be predicted with more precision no matter how much information we might have. This theoretical pursuit is different from statistical mechanics, in which Einstein did important work. Einstein did not like the part of quantum theory that denied anything more than the probability that something would be found to be true of something when it was actually measured; he thought that it should be possible to predict anything, if we had the correct theory and enough information. He once said, "I do not believe that God plays dice with the Universe."

Because Einstein helped science so much, his name is now used for several different things. A unit used in photochemistry was named for him. It is equal to Avogadro's number multiplied by the energy of one photon of light. The chemical element Einsteinium is named after the scientist as well.[25] In slang, we sometimes call a very smart person an "Einstein."

Criticism

Most scientists think that Einstein's theories of special and general relativity work very well, and they use those ideas and formulas in their own work. Einstein disagreed that phenomena in quantum mechanics can happen out of pure chance. He believed that all natural phenomena have explanations that do not include pure chance. He spent much of his later life trying to find a "unified field theory" that would include his general relativity theory, Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism, and perhaps a better quantum theory. Most scientists do not think that he succeeded in that attempt.

References

- During the German Empire, citizens were exclusively subjects of one of the 27 Bundesstaaten.

- How much Einstein is there in ETH Zurich? at YouTube

- Heilbron, John L., ed. (2003). The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science. Oxford University Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-19-974376-6.

- Pais (1982), p. 301.

- Whittaker, E. (1955). "Albert Einstein. 1879–1955". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 1: 37–67. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1955.0005. JSTOR 769242.

- The Nobel Prize biography states "He... remained in Berlin until 1933 when he renounced his citizenship for political reasons and emigrated to America... He became a United States citizen in 1940".

- "Albert Einstein – Biography". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 6 March 2007. Retrieved 7 March 2007.

- Fujia Yang; Joseph H. Hamilton (2010). Modern Atomic and Nuclear Physics. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-4277-16-7.

- Levenson, Thomas (9 June 2017). "The Scientist and the Fascist". The Atlantic.

- Paul S. Boyer; Melvyn Dubofsky (2001). The Oxford Companion to United States History. Oxford University Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-19-508209-8.

- Tamari, Vladimir; Feynman, Richard P. (1986). "Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!". Leonardo. 19 (4): 350. doi:10.2307/1578389. ISSN 0024-094X. JSTOR 1578389.

- "Albert Einstein – Biographical". nobelprize.org. 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- "Einstein: his Life and Universe" by Walter Isaacson

- Albert Einstein, Mileva Marić: The Love Letters, Princeton, N.J. 1992, p. 78

- Clark, Ronald W. (1984). Einstein:: The Life and Times. Harper Collins. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-380-01159-9.

- Albert Einstein on his decision not to accept the Presidency of Israel

- Olmert backs Peres as next president Jerusalem Post, 18 October 2006

- Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper Annalen der Physik Volume 322, Issue 10 Jan 1905 Pages fmi, 781-1020 1905 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim https://doi.org/10.1002/andp.19053221004

- George Gamow, One, Two, Three...Infinity, p. 170ff

- Los Alamos National Laboratory report LA-8819, The yields of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki nuclear explosions by John Malik, September 1985. Available online at http://www.mbe.doe.gov/me70/manhattan/publications/LANLHiroshimaNagasakiYields.pdf Archived 2008-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- "How Did Albert Einstein Die". End Of Stories. 19 December 2023. Archived from the original on 25 January 2024. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- Randerson, James (2008). "Childish superstition: Einstein's letter makes view of religion relatively clear." The Guardian (May 13). Concerns have been raised over The Guardian's English translation. Original letter (handwriting, German). Archived 2013-12-09 at the Wayback Machine "Das Wort Gott ist für mich nichts als Ausdruck und Produkt menschlicher Schwächen, die Bibel eine Sammlung ehrwürdiger aber doch reichlich primitiver Legenden.... Für mich ist die unverfälschte jüdische Religion wie alle anderen Religionen eine Incarnation des primitiven Aberglaubens." Transcribed here and here. Translated here and here. Copies of this letter are also located in the Albert Einstein Archives: 33-337 (TLXTr) Archived 2020-10-30 at the Wayback Machine, 33-338 (ALSX) Archived 2020-11-06 at the Wayback Machine, and 59-897 (TLTr). Archived 2020-11-04 at the Wayback Machine Alice Calaprice (2011). The Ultimate Quotable Einstein. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, p. 342, cites Einstein Archives 33-337.

- Overbye, Dennis (17 May 2008). "Einstein Letter on God Sells for $404,000". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- Bryner, Jeanna (5 October 2012). "Does God Exist? Einstein's 'God Letter' Does, And It's Up For Sale". NBC News. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- "Albert Einstein's 'God letter' sells for $2.9m". BBC News. 4 December 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- "Einsteinium named after Einstein". Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- Einstein, Albert and Infeld, Leopold 1938. The evolution of physics: from early concept to relativity and quanta. Cambridge University Press. A non-mathematical account.