| Sonnet 54 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

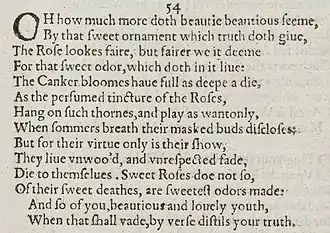

Sonnet 54 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 54 is one of 154 sonnets published in 1609 by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is considered one of the Fair Youth sequence. This sonnet is a continuation of the theme of inner substance versus outward show by noting the distinction between roses and canker blooms; only roses can preserve their inner essence by being distilled into perfume. The young man's essence or substance can be preserved by verse.[2]

Structure

Sonnet 54 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet contains three quatrains followed by a final rhyming couplet. This poem follows the rhyme scheme of the English sonnet, abab cdcd efef gg and is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of metre in which each line has five feet, and each foot has two syllables that are accented weak/strong. The fifth line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / The canker blooms have full as deep a dye

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus. (×) = extrametrical syllable.

The sixth and eighth lines end with feminine endings.

Synopsis

Sonnet 54 by William Shakespeare is divided into three quatrains and one heroic couplet. The first two quatrains work together, illustrating both the scentless canker bloom [3] and the scented rose. In the first two lines of the first quatrain he says that beauty seems more beauteous as a result of truth. In the next two he gives the example of a rose. He says that beyond its looks, we prize the rose for its scent. This scent is its "truth" or essence. In the second quatrain Shakespeare compares the rose to the canker bloom. They have similar in ways other than scent. Shakespeare's use of the words "play" and "wantonly" together implies that "play" has a sexual connotation.[4] In the third quatrain the author compares the death of the two flowers. The canker bloom dies alone and "unrespected", while roses do not die alone, for "of their sweet deaths are sweetest odours made". The final couplet indicates that the young man, or perhaps that which is beauteous and lovely, will enjoy a second life in verse, while that which is meaningless and shallow will be forgotten.[5] This distillation metaphor can be compared to sonnet 5, where marriage was the distiller and beauty was distilled.[6] In either sonnet one gets the same result from the distillation process, which is beauty. However, in sonnet 5 the distillation process is through marriage, and in sonnet 54 it is through verse. "Vade" in the final line is often used in a sense similar to "fade", but "vade" has stronger connotations of decay. In 1768, Edward Capell altered the final line by replacing the quarto's "by" with "my". This alteration was generally followed through the 19th Century. More recent editors do not favor this alteration, as it narrows the meaning from the larger principles of the sonnet.[7][8]

Roses

This poem is a comparison between two flowers that are representations of the youth's beauty. Shakespeare compares these flowers, which vary greatly in their appearance, although they are essentially the same kind of flower, the "canker-blooms" or wild roses, according to Katherine Duncan-Jones, are the less desirable then that of the, assumed, damask or crimson rose.[9] Since the wild roses do not prolong their beauty after death, they are not like the youth–who even after death shall be immortalized in the writers words of the sonnet.

Duncan Jones adds: "There is an additional problem about Shakespeare's contrast between 'The rose' and 'The canker blooms'. It is strongly implied that the latter have no scent, and cannot be distilled into rose-water: for their virtue only is their show. 'They live unwooed, and unrespected fade, Die to them selves. Sweet roses do not so ...' Yet it is clear that some wild roses, especially the sweet briar or eglantine, had a sweet, though not powerful, fragrance, and could be culled for distillation and conservation when better, red, roses were not available: their 'virtues' were identical".[9]

Literary influences

In Sonnet 54's third line "The rose looks fair, but fairer we it deem,” we see a reference to Edmund Spenser's Amoretti, Sonnet 26, the first line of which is "Sweet is the rose, but growes upon a brere." This reference is just one of many which help to "proclaim Shakespeare's deepest literary values and his recurrent aesthetic convictions."[10] While Shakespeare honors his contemporaries, one of the things that make Shakespeare great is how he differed from them. The Amoretti is a series of sonnets focused on a more traditional topic, the courting which led to Spencer's marriage. In the Amoretti, Spenser proposes "that a resolution to the sonneteer's conventional preoccupations with love may be found within the bounds of Christian marriage."[11]

Context in sonnet sequence

The context of the sonnets vary, but the first 126, amongst which sonnet 54 is found, are addressed to a young man of good social status and profess the narrator's platonic love. The love is returned, and the young man seems to yearn for the sonnets, as seen in sonnets 100-103 where the narrator apologizes for the long silence.[12] However, Berryman suggests that it is impossible to determine how the relationship ended up. While theories exist that the sonnets were written as literary exercises, H. C. Beeching suggests that they were written for a patron and not originally intended to be published together.[13]

Sexuality

In an analysis of Margreta de Grazia's essay about Shakespeare's sonnets, Robert Matz, mentions the subject of Shakespeare's sonnets (such as Sonnet 54) being written to a man. Drawing on a Foucauldian history of sexuality, De Grazia and Matz argue that while this notion appears scandalous in modernity, in Shakespeare's time this was not the same kind of issue. Sonnets written to a woman could have been considered more improper in Shakespeare's era because of the possible class difference and the idea of a woman's presumed promiscuity (originating in the idea of Eve causing the fall of man by enticing Adam to eat the forbidden fruit). According to Matz, "contemporary categories of or judgments about sexual desire may not cohere with past ones. De Grazia usefully argues that the changing reception of the sonnets marks a shift from an early modern concern with sex as a social category to modern understanding of sex as a personal one".[14] The notion of homosexuality versus heterosexuality is a modern development that simply did not exist in 16th century England. Readers may have disapproved of Shakespeare's same-sex love or male friendship before the mid-20th century but they would not have reacted to the text as Shakespeare presenting himself as a "homosexual". Rather they would have pointed to other sonnets to prove his heterosexuality, and therefore find consolation in that.[14]

Notes

- ↑ Shakespeare, William. Duncan-Jones, Katherine. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Bloomsbury Arden 2010. p. 219 ISBN 9781408017975.

- ↑ Shakespeare, William. Duncan-Jones, Katherine. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Bloomsbury Arden 2010. p. 218 ISBN 9781408017975.

- ↑ Shakespeare's Sonnets, edited by Stephen Booth (Google Books)

- ↑ Shakespeare's Sonnets, edited by Stephen Booth (Google Books)

- ↑ Shakespeare, William. Duncan-Jones, Katherine. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Bloomsbury Arden 2010. p. 219 ISBN 9781408017975.

- ↑ Beeching 96

- ↑ Hammond. The Reader and the Young Man Sonnets. Barnes & Noble. 1981. p. 69-70. ISBN 978-1-349-05443-5

- ↑ Shakespeare, William. Duncan-Jones, Katherine. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Bloomsbury Arden 2010. p. 218 ISBN 9781408017975.

- 1 2 Duncan-Jones, Katherine (1995). "Deep-Dyed Canker Blooms: Botanical Reference in Shakespeare's Sonnet 54". The Review of English Studies. 46 (184): 521–525. doi:10.1093/res/XLVI.184.521. JSTOR 519062. Gale A17963205.

- ↑ William J. Kennedy, "Shakespeare and the Development of English Poetry", The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's Poetry, ed. Patrick Cheney. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007

- ↑ Larsen, Kenneth J. Introduction. Edmund Spenser's Amoretti and Epithalamion: A Critical Edition. Tempe, AZ: Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies, 1997.

- ↑ Berryman, John. Berryman's Shakespeare. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1999. 287

- ↑ The Sonnets of Shakespeare, edited by H. C. Beeching GoogleBooks

- 1 2 Matz, Robert (2010). "The Scandals of Shakespeare's Sonnets". ELH. 77 (2): 477–508. doi:10.1353/elh.0.0082. S2CID 161914623. Project MUSE 382796.

References

- Matz, Robert (2010). "The Scandals of Shakespeare's Sonnets". ELH. 77 (2): 477–508. doi:10.1353/elh.0.0082. S2CID 161914623. Project MUSE 382796.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine (1995). "Deep-Dyed Canker Blooms: Botanical Reference in Shakespeare's Sonnet 54". The Review of English Studies. 46 (184): 521–525. doi:10.1093/res/XLVI.184.521. JSTOR 519062. Gale A17963205.

- The Sonnets of Shakespeare, edited by H. C. Beeching Google Books

- Berryman, John. Berryman's Shakespeare. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1999.

- Schiffer, James. Shakespeare's Sonnets. New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1999

- Kennedy, William J. "Shakespeare and the Development of English Poetry", The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's Poetry, ed. Patrick Cheney. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Larsen, Kenneth J. Introduction. Edmund Spenser's Amoretti and Epithalamion: A Critical Edition. Tempe, AZ: Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies, 1997.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485. — Volume I and Volume II at the Internet Archive

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. Arden Shakespeare, third series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951. — 1st edition at the Internet Archive

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

.png.webp)