| Sonnet 110 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

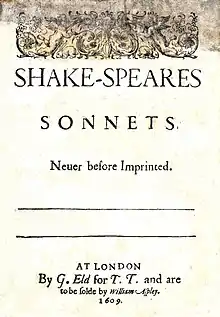

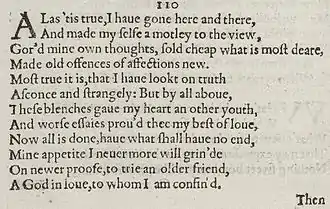

The first three stanzas of Sonnet 110 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 110 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. Sonnet 110 was published along with the other sonnets in the 1609 Quarto. The sonnet falls in place with the Fair Youth sequence of Shakespeare's sonnets, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man. The mystery of the young man is still unknown today. However, there are many different theories by various scholars of who this young man may be. There has been much debate whether or not this sonnet was written about Shakespeare's disdain with the stage and actors. Whereas others have interpreted sonnet 110 as the poet confessing his love to a young man.

The sonnet is a confession of the poets committed sins and promiscuity, which quickly escalates to his confession of love to the young man. With Shakespeare's heavy use of double meanings to words have scholars perplexed as to whether the sonnet is about Shakespeare's career as an actor or a confession of love to the young man. The sonnet is written in traditional Shakespearean sonnet form consisting of 14 lines with Iambic Pentameter and ending with a couplet.

Paraphrase

The poet confesses to profligate and dishonest behaviour, but these faults have revitalised him. He will no longer look elsewhere but devote himself to the young man, who he hopes will welcome him back.

Below is scholar David West's paraphrase translated to modern English:

It's true. I have ranged widely, made myself a fool, squandered my treasure, and hurt my old lover by taking a new. I have truly given truth a sideways glance, but I swear this brought youth back to my heart. Experiment proved that you are the best that love has to offer. It is ended. Take what will not end. Never again will I whet my appetite on new loves to test the old, my one and only god of love. You are next to my heaven. Take me back to your pure and loving breast.[2]

Structure

Sonnet 110 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the typical rhyme scheme of the form ABAB CDCD EFEF GG and is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The 7th line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / These blenches gave my heart another youth, (110.7)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

Lines 3 and 14 have initial reversals, and the 9th line has a mid-line reversal ("have what"):

× / × / / × × / × / Now all is done, have what shall have no end: (110.9)

The meter demands that line 13's "heaven" and line 14's "even" each function as one syllable.[3]

Context

Although the sonnets were published in 1609, the exact date of when they were written is unclear. It is estimated that the sonnets could have been written between 1588 and 1593. The sonnets are written about two characters in particular: the Dark Lady and an unknown young man. Scholar Kenneth Muir states that the first 126 sonnets were written about a man and the others were written about the Dark Lady.[4] The identity of the young man is still a mystery today. The only clue that was left about who this young man may be is Shakespeare's dedication to a "Mr. W.H". There has been much speculation of whether who this young man may be. Many scholars have their own idea of who "Mr. W.H." may be. In Raymond Macdonald Alden's book, he has a chapter dedicated to who "the friend's" true identity may be.[5] William Harte was one name that was thrown out there. William Harte was Shakespeare's nephew but the dates do not match up with the sonnet. Scholar Tyrwhitt suggests the name William Hughes. This name was quite the popular choice. The list goes on and on. Scholars thought any man with the initials "W.H." that were active around the same time the sonnets were written could have been this mystery man. Mr. W.H. will remain a mystery till this day.

Exegesis

Overview

It has been debated by many critics and scholars whether or not sonnet 110 was written about Shakespeare's career in the theater or if the sonnet is a confession of love to a young man. The lines in the sonnet could be related to the stage but scholars Virginia L. Radley and David C. Redding disagree stating that sonnet 110 is, "addressed to an old friend of the poet's."[6] Sonnet 110 can be interpreted as a confession of love and the mistakes the poet made when he decided to leave his original love. The poet confesses to the young man his infidelities and regrets in order to receive pity from the young man for what the poet did was wrong but should be forgiven since he claimed the young man is the best person he will ever love.

Quatrain 1

There have been many arguments by scholars whether or not the sonnet was written about Shakespeare's disdain with the stage and his career in the theater, or if the sonnet is a confession of love to an unknown young man. Shakespeare's use of the word motley has the mind of critics and scholars boggled as to what the sonnet could truly mean. A motley is a multi-colored gown, or costume, usually worn by a jester. Many scholars believe that the sonnet is written about Shakespeare's disdain with the theater and the actors, or even his own profession as an actor. Katherine Duncan-Jones believes that the sonnet is about Shakespeare's feelings about his own career as an actor.[7] Scholar Henry Reed agrees with Duncan-Jones and believes that the sonnet is written about Shakespeare's own disdain with his acting career.[8] The third line of the quatrain also suggests that the sonnet could be about the theater. Gored could be used in the sense of sewing triangular sized cloths into the motley that would be worn by the actor.[2] However, there are other scholars that would disagree with the two. Among these scholars is Kenneth Muir who says, "the theatrical image does not imply that he was referring to his job as an actor."[9] According to Virginia Radley and David Redding, the interpretation of the sonnet being about Shakespeare's profession as an actor is wrong. Radley and Redding suggests that "sonnet 110 has nothing to do with the stage, or the acting, or the play writing."[6] Radley and Redding interpreted the first quatrain as the poets confession of promiscuity. Lines 1-2 suggests that the poet has been around and has made a fool of himself for the world to see. Here, the word motley is used as in "I played the fool."[10] Line 3 suggests that the poet put himself on display and gave away his precious love. With the use of the word gored, Radley and Redding translated the phrase "gored mine own thoughts" to "wounded my best thoughts".[6] The last line of this quatrain uses the word offences is used in the correct term as in offending the poet's lover by this new affairs he has encountered. By the end of this quatrain, the reading of the sonnet slowly becomes clear that this a confession of love versus Shakespeare's disdain with the theater.

Quatrain 2

Quatrain 2 continues with the poet confessing about his journey on finding false love. In line 5, the phrase "looked on truth" is used in terms that the poet has seen what is true. Scholar Stephen Booth has interpreted the line: "I have seen truth, but I have not properly regarded it."[11] Booth's interpretation gives insight about the poet's disregard for the lover's affection. Line 5 continuing onto line 6 can be interpreted about the poet's journey of promiscuity and finding new lovers. The use of the word "askance" is used in this case as the poet's disdain with the affairs he has encountered.[11] "Askance and strangely" are used to describe how none of these loves compare to what he had experienced with this young man. The word blenches can be translated into modern English as a flaw. The interpretation of line 7 can mean that these flawed affairs gave me a blink of youth. Booth has multiple interpretations of what this line could possibly mean. His interpretations is that it "rejuvenated [the poet] and gave [him] another chance to learn by trial and error" or that it "rejuvenated [his love]".[12] The end of this quatrain ends the poets confession of failed attempts of finding the ideal love and starts his confession of love to the young man. The last line is a very powerful way to end the quatrain and start the next section. "Worse essays" is used in this line to describe the failed "experiments" of the poet. The failed experiments proved that the young man is the best love that he has encountered.

Quatrain 3

As the sonnet is coming to an end, the poet expresses his devotion. He explains how he is done trying to find new affections. Radley and Redding explain that the "no end" he speaks of is his undying devotion.[13] He no longer wants to go through these trials. He explains how he is done trying to find new affections. He realizes over the course of his quest that he ends up back to the young man, which is where he originally began on his quest. The use of "on newer proof" is used as a description of the poet's trials he went through to come up with this conclusion of full devotion. He continues to express to the young man that he is "confined" to him, promising him to never stray away from the young man when temptations arise. The use of the word confine suggests that the poet is fully devoted to the young man. He is only "limited" to the young man.[14]

Couplet

The couplet brings the sonnet together in a happy light. Throughout the sonnet we're learning about the poet's dark confessions to finding his ideal love and realizing the only love that he needs the most is of the young mans. Jane Roessner notices how the line "then give me welcome, next my heaven the best" is "the poet's need of pity from the young man and how his long confession important for its effect on the young man, calculated to move him to a certain response."[15] Line 13 is the poet begging the young man to forgive him and to embrace him. The phrase in line 13 "next my heaven the best" is the poet confessing to the young man that his love is like his heaven. He is the closest thing to the divine. Radley and Redding state that the poet is saying, "your love is next of the divine (ideal), grant me a welcome sanctuary in your person."[13] The couplet is the most powerful part of the sonnet because now he is saying that the love the young man provides is great next to this divine being.

References

- ↑ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- 1 2 West, David (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets. New York: The Overlook Press. p. 337.

- ↑ Booth 2000, p. 358.

- ↑ Muir, Kenneth (1983). College Literature. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 244.

- ↑ Alden, Raymond Macdonald (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 469–471.

- 1 2 3 Radley, Redding, Virginia L, David C (1961). Shakespeare Quarterly. Folger Shakespeare Library. p. 462.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Duncan-Jones, Katherine (2009). The Review of English Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 723.

- ↑ Alden, Raymond Macdonald (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 257.

- ↑ Muir, Kenneth (1979). Shakespeare's Sonnets. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. p. 77.

- ↑ Booth, Stephen (1977). Shakespeare's Sonnets. Massachusetts: The Murray Printing Co., Inc. p. 354. ISBN 0-300-01959-9.

- 1 2 Booth, Stephen (1977). Shakespeare's Sonnets. Massachusetts: The Murray Printing Co., INC. p. 355. ISBN 0-300-01959-9.

- ↑ Booth, Stephen (1977). Shakespeare's Sonnets. Massachusetts: The Murray Printing Co., Inc. p. 356. ISBN 0-300-01959-9.

- 1 2 Radley, Redding, Virginia L, David C (1961). Shakespeare Quarterly. Folger Shakespeare Library. p. 463.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Booth, Stephen (1977). Shakespeare's Sonnets. Massachusetts: The Murray Printing Co., INC. p. 357. ISBN 0-300-01959-9.

- ↑ Roessner, Jane (1979). Double Exposure: Shakespeare's Sonnets 100-114. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 373.

Further reading

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485. — Volume I and Volume II at the Internet Archive

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. Arden Shakespeare, third series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951. — 1st edition at the Internet Archive

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

.png.webp)