| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

(C70-D5h(6))[5,6]Fullerene[1] | |

| Other names

Fullerene-C70, rugbyballene | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.162.223 |

PubChem CID |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C70 | |

| Molar mass | 840.770 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Dark needle-like crystals |

| Density | 1.7 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | sublimates at ~850 °C[2] |

| insoluble in water | |

| Band gap | 1.77 eV[3] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Nanomaterials |

|---|

|

| Carbon nanotubes |

| Fullerenes |

| Other nanoparticles |

| Nanostructured materials |

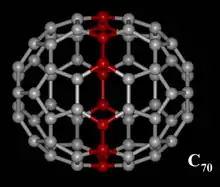

C70 fullerene is the fullerene molecule consisting of 70 carbon atoms. It is a cage-like fused-ring structure which resembles a rugby ball, made of 25 hexagons and 12 pentagons, with a carbon atom at the vertices of each polygon and a bond along each polygon edge. A related fullerene molecule, named buckminsterfullerene (or C60 fullerene) consists of 60 carbon atoms.

It was first intentionally prepared in 1985 by Harold Kroto, James R. Heath, Sean O'Brien, Robert Curl and Richard Smalley at Rice University. Kroto, Curl and Smalley were awarded the 1996 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their roles in the discovery of cage-like fullerenes. The name is a homage to Buckminster Fuller, whose geodesic domes these molecules resemble.[4]

History

Theoretical predictions of buckyball molecules appeared in the late 1960s to early 1970s,[5] but they went largely unnoticed. In the early 1970s, the chemistry of unsaturated carbon configurations was studied by a group at the University of Sussex, led by Harry Kroto and David Walton. In the 1980s a technique was developed by Richard Smalley and Bob Curl at Rice University, Texas to isolate these substances. They used laser vaporization of a suitable target to produce clusters of atoms. Kroto realized that by using a graphite target.[6]

C70 was discovered in 1985 by Robert Curl, Harold Kroto and Richard Smalley. Using laser evaporation of graphite they found Cn clusters (for even n with n > 20) of which the most common were C60 and C70. For this discovery they were awarded the 1996 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. The discovery of buckyballs was serendipitous, as the scientists were aiming to produce carbon plasmas to replicate and characterize unidentified interstellar matter. Mass spectrometry analysis of the product indicated the formation of spheroidal carbon molecules.[5]

Synthesis

In 1990, K. Fostiropoulos, W. Krätchmer and D. R. Huffman developed a simple and efficient method of producing fullerenes in gram and even kilogram amounts which boosted fullerene research. In this technique, carbon soot is produced from two high-purity graphite electrodes by igniting an arc discharge between them in an inert atmosphere (helium gas). Alternatively, soot is produced by laser ablation of graphite or pyrolysis of aromatic hydrocarbons. Fullerenes are extracted from the soot using a multistep procedure. First, the soot is dissolved in appropriate organic solvents. This step yields a solution containing up to 70% of C60 and 15% of C70, as well as other fullerenes. These fractions are separated using chromatography.[7]

Properties

Molecule

The C70 molecule has a D5h symmetry and contains 37 faces (25 hexagons and 12 pentagons) with a carbon atom at the vertices of each polygon and a bond along each polygon edge. Its structure is similar to that of C60 molecule (20 hexagons and 12 pentagons), but has a belt of 5 hexagons inserted at the equator. The molecule has eight bond lengths ranging between 0.137 and 0.146 nm. Each carbon atom in the structure is bonded covalently with 3 others.[8]

C70 can undergo six reversible, one-electron reductions to C6−

70, whereas oxidation is irreversible. The first reduction requires around 1.0 V (Fc/Fc+

), indicating that C70 is an electron acceptor.[9]

Solution

| Solvent | S (mg/mL) |

|---|---|

| 1,2-dichlorobenzene | 36.2 |

| carbon disulfide | 9.875 |

| xylene | 3.985 |

| toluene | 1.406 |

| benzene | 1.3 |

| carbon tetrachloride | 0.121 |

| n-hexane | 0.013 |

| cyclohexane | 0.08 |

| pentane | 0.002 |

| octane | 0.042 |

| decane | 0.053 |

| dodecane | 0.098 |

| heptane | 0.047 |

| isopropanol | 0.0021 |

| mesitylene | 1.472 |

| dichloromethane | 0.080 |

Fullerenes are sparingly soluble in many aromatic solvents such as toluene and others like carbon disulfide, but not in water. Solutions of C70 are a reddish brown. Millimeter-sized crystals of C70 can be grown from solution.[11]

Solid

Solid C70 crystallizes in monoclinic, hexagonal, rhombohedral, and face-centered cubic (fcc) polymorphs at room temperature. The fcc phase is more stable at temperatures above 70 °C. The presence of these phases is rationalized as follows. In a solid, C70 molecules form an fcc arrangement where the overall symmetry depends on their relative orientations. The low-symmetry monoclinic form is observed when molecular rotation is locked by temperature or strain. Partial rotation along one of the symmetry axes of the molecule results in the higher hexagonal or rhombohedral symmetries, which turn into a cubic structure when the molecules start freely rotating.[3][12]

All phases of C70 form brownish crystals with a bandgap of 1.77 eV;[3] they are n-type semiconductors where conductivity is attributed to oxygen diffusion into the solid from atmosphere.[13] The unit cell of fcc C70 solid contains voids at 4 octahedral and 12 tetrahedral sites.[14] They are large enough to accommodate impurity atoms. When electron-donating elements, such as alkali metals, are doped into these voids, C70 converts into a conductor with conductivity up to around 2 S/cm.[15]

| Symmetry | Space group | No | Pearson symbol | a (nm) | b (nm) | c (nm) | Z | Density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoclinic | P21/m | 11 | mP560 | 1.996 | 1.851 | 1.996 | 8 | |

| Hexagonal | P63/mmc | 194 | hP140 | 1.011 | 1.011 | 1.858 | 2 | 1.70 |

| Cubic | Fm3m | 225 | cF280 | 1.496 | 1.496 | 1.496 | 4 | 1.67 |

References

- ↑ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (2014). Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013. The Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 325. doi:10.1039/9781849733069. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ↑ Eiji Ōsawa (2002). Perspectives of fullerene nanotechnology. Springer. pp. 275–. ISBN 978-0-7923-7174-8. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 Thirunavukkuarasu, K.; Long, V. C.; Musfeldt, J. L.; Borondics, F.; Klupp, G.; Kamarás, K.; Kuntscher, C. A. (2011). "Rotational Dynamics in C70: Temperature- and Pressure-Dependent Infrared Studies". The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 115 (9): 3646–3653. doi:10.1021/jp200036t.

- ↑ Press Release. Nobel Prize Foundation. 9 October 1996

- 1 2 Katz, 363

- ↑ Katz, 368

- ↑ Katz, 369–370

- ↑ Rao, C.N.R.; Seshadri, Ram; Govindaraj, A.; Sen, Rahul (1995). "Fullerenes, nanotubes, onions and related carbon structures". Materials Science and Engineering: R. 15 (6): 209–262. doi:10.1016/S0927-796X(95)00181-6.

- ↑ Buckminsterfullerene, C60. University of Bristol. Chm.bris.ac.uk (1996-10-13). Retrieved on 2011-12-25.

- ↑ Bezmel'nitsyn, V.N.; Eletskii, A.V.; Okun', M.V. (1998). "Fullerenes in solutions". Physics-Uspekhi. 41 (11): 1091. Bibcode:1998PhyU...41.1091B. doi:10.1070/PU1998v041n11ABEH000502.

- ↑ Talyzin, A.V.; Engström, I. (1998). "C70 in Benzene, Hexane, and Toluene Solutions". Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 102 (34): 6477. doi:10.1021/jp9815255.

- 1 2 Verheijen, M.A.; Meekes, H.; Meijer, G.; Bennema, P.; De Boer, J.L.; Van Smaalen, S.; Van Tendeloo, G.; Amelinckx, S.; Muto, S.; Van Landuyt, J. (1992). "The structure of different phases of pure C70 crystals" (PDF). Chemical Physics. 166 (1–2): 287–297. Bibcode:1992CP....166..287V. doi:10.1016/0301-0104(92)87026-6. hdl:2066/99047.

- ↑ Fabiański, Robert; Firlej, Lucyna; Zahab, Ahmed; Kuchta, Bogdan (2002). "Relationships between crystallinity, oxygen diffusion and electrical conductivity of evaporated C70 thin films". Solid State Sciences. 4 (8): 1009–1015. Bibcode:2002SSSci...4.1009F. doi:10.1016/S1293-2558(02)01358-4.

- ↑ Katz, 372

- ↑ Haddon, R. C.; Hebard, A. F.; Rosseinsky, M. J.; Murphy, D. W.; Duclos, S. J.; Lyons, K. B.; Miller, B.; Rosamilia, J. M.; Fleming, R. M.; Kortan, A. R.; Glarum, S. H.; Makhija, A. V.; Muller, A. J.; Eick, R. H.; Zahurak, S. M.; Tycko, R.; Dabbagh, G.; Thiel, F. A. (1991). "Conducting films of C60 and C70 by alkali-metal doping". Nature. 350 (6316): 320–322. Bibcode:1991Natur.350..320H. doi:10.1038/350320a0. S2CID 4331074.

Bibliography

- Katz, E. A. (2006). "Fullerene Thin Films as Photovoltaic Material". In Sōga, Tetsuo (ed.). Nanostructured materials for solar energy conversion. Elsevier. pp. 361–443. ISBN 978-0-444-52844-5.