| |

| |

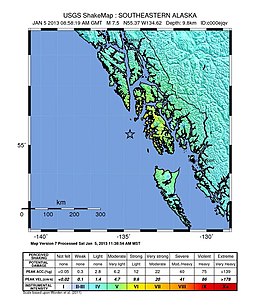

| UTC time | 2013-01-05 08:58:14 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 602213332 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | 5 January 2013 |

| Local time | 12:58 am |

| Magnitude | Mw 7.5 Ms 7.7 |

| Depth | 8.7 km (5.4 mi) |

| Epicenter | 55°13′41″N 134°51′32″W / 55.228°N 134.859°W |

| Fault | Queen Charlotte Fault |

| Type | Strike-slip |

| Areas affected | British Columbia and Alaska |

| Total damage | None |

| Max. intensity | V (Moderate) [1] |

| Tsunami | 1.5 meters (seiches) |

| Landslides | No |

| Aftershocks | Yes Largest: 5.9 Mw |

| Casualties | None |

The 2013 Craig, Alaska earthquake (also known as the Queen Charlotte Fault earthquake) struck on January 5, at 12:58 am (UTC–7) near the city of Craig and Hydaburg, on Prince of Wales Island. The Mw 7.5 earthquake came nearly three months after an Mw 7.8 quake struck Haida Gwaii on October 28, in 2012.[2] The quake prompted a regional tsunami warning to British Columbia and Alaska, but it was later cancelled.[3] Due to the remote location of the quake, there were no reports of casualties or damage.

Tectonic setting

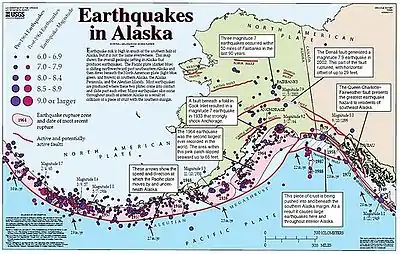

The Queen Charlotte Fault is a major right-lateral (dextral) strike-slip and transform fault running off the coast of British Columbia and into Southern Alaska, through the Saint Elias Range for more than 700 miles.[4] Its southernmost section joins a spreading ridge of the Gorda Plate and the Cascadia subduction zone while the northern termination section joins the a thrust fault where the Yakutat terrane plows into the North American Plate. It has been the source of several large earthquakes in the 20th century, and appears that much of its length has ruptured in these events. In 1949, it produced a magnitude 8.1 earthquake off the west coast of Haida Gwaii, then in 1958, a magnitude 7.8 earthquake generated a megatsunami more than 500 meters tall, killing five people. Other earthquakes in the region include a 7.6 near Sitka, and the 2012 event. The Queen Charlotte Fault bears a similar resemblance with California's San Andreas Fault, another transform fault to the south.

Earthquake

The rupture zone is situated on a seismic gap between fault segments which ruptured in 1972 to its north, and the other to the south in 1949.[5][6] The largest earthquake prior to the 7.5 quake along this gap was a magnitude 6.8 to the south of the 2013 epicenter.[7] The 2013 earthquake ruptured for a length of 150 km (93 mi), 322 km (200 mi) north of the 2012 event.[4] A note to take into account, the 2012 temblor had a focal mechanism of thrust rather than strike-slip, like those observed along the fault. That earthquake was on the interface of the subducting Pacific Plate as it is underthrusted beneath the North American Plate.[8] The Craig earthquake, on the other hand, was a near pure strike-slip event which was probably in response to stress transfer from the quake four months ago.[8]

Characteristic

Research found that the earthquake was a rare supershear event, and was the first of its kind to occur on an oceanic plate boundary. Supershear rupture initiated along the northern rupture zone for about 100 km with a velocity of 5.5 to 6.0 km/s, much faster that the propagation velocity of the S-waves.[9][10] The rupture propagated northwards, away from the epicenter, with an initial rupture velocity of 3.0 km.[10] This subshear rupture continued for the first 30 to 50 km. Afterward, the rupture velocity exceeded the S-wave propagation speed of 3.8 km/s, reaching 7.0 km/s through the upper crust at its highest.[11]

Aftershocks

More than 290 aftershocks greater than magnitude 2.5 were recorded in the aftermath of the earthquake from 2013 to 2020. Most of them were along other fault structures away from the main fault. This is also commonly seen in other supershear earthquakes.[9] The largest aftershocks were of magnitude 5.9, 5.5 and 5.2 which occurred on a different fault from the mainshock.[12][13][14]

Impact

A maximum intensity of V (Moderate) was felt in Craig, Hydaburg, Klawock and Hyder without damage,[1] but there were reports of items falling off shelves. The earthquake was mildly felt as far away in Seattle, Washington.[15] A tsunami warning was broadcast from Cape Fairweather, Alaska to northern Vancouver Island, while a tsunami advisory was issued to the coast of Washington. It was later canceled after no large waves were observed.[16] The shock frightened many who fled to higher grounds to avoid the tsunami.

Tsunami

Because the earthquake was of almost pure strike-slip mechanism, only small waves were produced without damage. These waves were up to 14 cm high.[17] Seiches up to 1.5 meters high were also recorded at Deer Lake, Alaska, north of Port Alexander. The small waves however, were not detected by Ocean Networks Canada.[18]

See also

References

- 1 2 "M 7.5 - 110 km SW of Edna Bay, Alaska". earthquake.usgs.gov. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ↑ "M 7.8 - Haida Gwaii, Canada". USGS-ANSS. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ "7.5-magnitude earthquake strikes off coast of Alaska; tsunami warning canceled". CNN. 5 January 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- 1 2 "Queen Charlotte-Fairweather Fault". Sitka Sound Science Center. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ↑ "2013 M7.5 QUEEN CHARLOTTE FAULT EARTHQUAKE". Alaska Earthquake Center. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ "M 7.6 - Southeastern Alaska". USGS-ANSS. Retrieved 11 Dec 2020.

- ↑ "M 6.8 - Southeastern Alaska". USGS-ANSS. Retrieved 11 Dec 2020.

- 1 2 Hyndman, R. D. (May 2015). "Tectonics and Structure of the Queen Charlotte Fault Zone, Haida Gwaii, and Large Thrust Earthquakes" (PDF). Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 105 (2B): 1058–1075. Bibcode:2015BuSSA.105.1058H. doi:10.1785/0120140181.

- 1 2 Han Yue; Thorne Lay; Jeffrey T. Freymueller; Kaihua Ding; Luis Rivera; Natalia A. Ruppert; Keith D. Koper (3 November 2013). "Supershear rupture of the 5 January 2013 Craig, Alaska (Mw 7.5) earthquake". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 118 (11): 5903–5919. Bibcode:2013JGRB..118.5903Y. doi:10.1002/2013JB010594. S2CID 3754158.

- 1 2 Maureen A.L. Walton, Emily C. Roland , Jacob I. Walter, Sean P.S. Gulick, Peter J. Dotray (2019). "Seismic velocity structure across the 2013 Craig, Alaska rupture from aftershock tomography: Implications for seismogenic conditions" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 507: 94–104. Bibcode:2019E&PSL.507...94W. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2018.11.021. S2CID 133784498.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Jin Fang, Caijun Xu, Yangmao Wen, Shuai Wang, Guangyu Xu, Yingwen Zhao and Lei Yi (3 June 2019). "The 2018 Mw 7.5 Palu Earthquake: A Supershear Rupture Event Constrained by InSAR and Broadband Regional Seismograms". Remote Sensing. 11 (11): 1330. Bibcode:2019RemS...11.1330F. doi:10.3390/rs11111330.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "M 5.9 - 101km W of Craig, Alaska". USGS-ANSS. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ↑ "M 5.5 - Southeastern Alaska". USGS-ANSS. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ↑ "M 5.2 - Southeastern Alaska". USGS-ANSS. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ↑ "Earthquake Event Information ALASKA: SOUTHEASTERN". NGDC. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ↑ "Alaska Gets All Clear After Quake and Tsunami Alert". The New York Times. Associated Press. 5 January 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ "TSUNAMI of 5 January, 2013 (WSW Craig, Alaska)". National Tsunami Warning Center. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ↑ "Negligible Tsunami From Alaska Earthquake". Oceans Networks Canada. 5 January 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2020.