—Welcoming new and useful ideas

Introduction

Creativity is the formation of new and useful ideas.

Although it has been argued that everyone is creative,[1] results vary widely. This course explores the opportunities of establishing the right organizational climate as an important factor for unleashing creativity.

Objectives

| Completion status: this resource is considered to be complete. |

| Attribution: User lbeaumont created this resource and is actively using it. Please coordinate future development with this user if possible. |

The objectives of this course are to:

- Highlight the importance of organizational climate in encouraging creativity

- Identify climate factors that encourage creativity;

- Identify actions that can enhance these encouraging factors;

- Identify climate factors that discourage creativity;

- Identify actions that can diminish or remove these discouraging factors;

- Help you establish a climate that unleashes creativity.

This is the first course in the possibilities curriculum, currently being developed and also part of the Applied Wisdom Curriculum.

The course contains many hyperlinks to further information. Use your judgment and these link following guidelines to decide when to follow a link, and when to skip over it.

If you wish to contact the instructor, please click here to send me an email or leave a comment or question on the discussion page.

Climate

What is it like to work here?

The climate of an organization consists of the recurring patterns of behaviors, attitudes, and feelings that characterize life in the organization. Participants within the organization perceive and experience climate as a relatively enduring quality of the organization. Climate influences an individuals’ behavior and can be described by a particular set of environmental characteristics, such as those discussed below.[2] Some climates encourage creativity and others discourage it.

In 1996 Göran Ekcall studied the effects of ten organizational structure and climate dimensions on creativity and innovation.[3] The ten dimensions studied are: challenge, freedom, idea support, trust/openness, dynamism/liveliness, playfulness/humor, debates, conflicts (negatively correlated), risk taking, and idea time.

These are described more fully below.[4]

Challenge

Are you excited to engage in this challenge?

The challenge dimension measures the members’ emotional involvement in the goals and operations of the organization. In a high-challenge climate people are joyful and invest great energy in their work because they find the work meaningful. People are involved in daily operations, long-term goals, and visions. In a low-challenge climate, people feel alienated and indifferent. Apathy and lack of interest are the common sentiments and attitudes.

Freedom

Can you decide for yourself who to talk to, what to explore, and the alternatives to consider?

Freedom allows people in the organization to act independently. In a climate characterized by freedom, people make contacts where they give and receive information; discuss problems; identify alternatives, plan actions; take various initiatives; and make decisions. People exercise autonomy and agency. This contrasts with a climate where people are passive, rule-bound, and anxious to stay within established boundaries.

Idea Support

When you share an idea, do people take time to understand the idea and highlight how it might work, or do they immediately list reasons why it will fail?

New ideas, especially unusual or nascent ideas, may be embraced and developed, or may be ignored, diminished, dismissed, or ridiculed. In a supportive climate new ideas are given attention, consideration, and support. People listen carefully and generously to each other, work to understand the idea, explore its possibilities, and contribute to its further acceptance and development. The atmosphere is constructive and positive, even when the idea is new, unusual, weird, or undeveloped. Intellectual safety prevails. By contrast, in an unsupportive climate, new ideas are immediately ignored or dismissed. Each new idea is met with objections and counterarguments. Faults are found and obstacles are raised until each new idea is killed off before it has a chance to live.

Trust / Openness

Do you trust the coworkers? Do they trust you? Are you able to assume coworkers have positive intent?

The trust / openness dimension addresses the emotional safety existing in relationships. When there is a strong level of trust it becomes safe to share ideas and opinions, even if those ideas and opinions challenge the norm, have been tried before, are not well developed, or seem a bit way-out. Initiatives can proceed without the fear of reprisals or ridicule, even if the initiative fails. Communication is open, candid, honest, and straightforward. In contrast, fear dominates when trust is lacking. People are suspicious of each other and wary of being caught making some mistake. People fear being exploited, or having their good ideas misrepresented, misattributed, or stolen. Fear displaces curiosity.

Dynamism / Liveliness

Is the group active or is everyone bored, passive, and inactive?

What is the energy level, activity, and eventfulness of the organization? In a lively and dynamic organization new things happen often, new issues arise, new viewpoints emerge, and new ways of solving problems are routinely found. A psychological turbulence predominates that is described as “full speed”, “go”, “breakneck” “maelstrom”, or similar terms. In contrast, a low energy, static organization proceeds slowly and methodically with no surprises; it is always business as usual. No new projects, no different plans, no new solutions, just more of the same old stuff every day.

Playfulness / Humor

Is this work fun or is it gloomy?

An easy spontaneity prevails in a playful climate. Good-natured jokes, laughter, and a relaxed atmosphere contribute to the task at hand. Working is fun, and jokes are part of that fun. This contrasts with a grave and serious atmosphere that is stiff, gloomy, and cumbersome. Here the work is much too serious to joke about.

Debates

Are differences explored and discussed or are they suppressed?

When viewpoints, ideas, and differing experiences and knowledge clash, deliberations[5] ensue. Many different voices and points of view are exchanged and encouraged, more ideas are offered, new insights occur, people listen to each other, respect is maintained, and new possibilities often appear. Dialogue leads to insight. This contrasts with climates that ignore or suppress conflict, submit to authoritarian patterns, inhibit curiosity, and avoid questioning the proceedings.

Conflicts

Are conflicts resolved, or do they remain unaddressed, unresolved, and escalate?

Although conflicts between ideas are encouraged and deliberated in a creative climate, unresolved personal and emotional tensions divert creativity from the task toward revenge. When salient personal conflicts are unresolved aggression and retaliation prevail. People engage in interpersonal warfare. Plots, traps, getting even, revenge, retaliation, and other interpersonal mischief dominate. Gossip and slander are common, long-lasting, underhanded, and tolerated. In contrast, people use impulse control, emotional competency, task orientation, and personal responsibility to resolve interpersonal conflicts in a creative climate.

Risk Taking

Is it OK to take a risk and fail?

Uncertainty is tolerated in a risk-taking climate. In a high Risk-Taking climate people can make decisions even when they do not have certainty and all the information desired. People can and do “go out on a limb” to put new ideas forward. Decisions and actions are prompt, new opportunities are seized, and experiments often inform decisions to avoid analysis paralysis. In contrast, people in risk averse climates are cautious and hesitant. People prefer the “safe side”, they “sleep on the matter”, set up committees to “study the problem” and find ways to cover themselves in case the decision, delay, or indecision turns out badly.

Idea Time

Can you spend time just thinking about the problem, or do you always have to look busy?

When idea time is valued, its OK to spend time creating, developing, elaborating, understanding, and discussing ideas. There are opportunities to discuss and test impulses and fresh ideas that emerge unexpectedly. Schedules are flexible and blue-sky thinking is recognized as a good use of time, not a waste of time. This contrasts with a rigid climate where every minute is reserved for some specified task-oriented kinetic activity. No time is available for developing ideas because we all need to get back to real work and appear busy.

Assessments

A variety of assessment instruments can help measure these climate elements. Here are some that are available:

Assignment

- Identify some partnership, collaboration, team, committee, club, work group, or other organization you are a member of where the creative results are disappointing. Select one to study for this assignment.

- Choose a creative climate assessment tool from those listed above.

- Gain approval of the members of the organization to assess the organizational climate.

- Use that assessment tool to measure the climate of your organization.

- Study the results and discuss them with the other members of the organization.

- Work together to identify actions you can take to improve the creative climate.

- Take those actions.

- Reassess the climate sometime after the corrective actions have been put in place and have begun to effect change.

Techniques

Various techniques can help enhance the creative climate. Together these positive behaviors create a climate that encourages people to reduce defensive postures they may have developed from previous negative experiences.[9]

Provide the Basics

Ensure the team has adequate physical space, comfortable surroundings, a variety of seating options, food, beverages, refreshments, adequate rest, work areas, electrical power, internet connections, reference materials, supplies for taking notes, recording ideas, and illustrating concepts; quiet areas, private areas, and open spaces that can be explored to provide new and varied surroundings that allow for wandering around, stretching your legs, taking a break, or allow some other way to refresh.

Ensure each participant can clearly hear what each person is saying and see what each person may be illustrating, displaying, or demonstrating.

Focus on what matters

If you are not excited by the challenge of the work the group is about to undertake, it is important to address this gap. Whose problem is this? How was the assignment chosen? Who believes this is an important and worthy goal? Do you believe this is an important and worthy goal? Why or why not? Dialogue with people who chose or assigned the task to understand why they find it is important and to determine if you can also become excited by the importance of the work.

Complete the Wikiversity course on what matters. If the work of the group matters to you, then give it your best. If you are not excited by the challenge, then it may be best to explicitly disengage from the work and move on to some other challenge that does excite you.

Earn Trust

When two people meet they make assumptions about the level of trust they are willing to extend to each other.[10] Creativity is encouraged when everyone assumes everyone has positive intent. This is a bold act of trust.

A lack of trust among group members will greatly discourage creativity and productivity. If a formal or informal assessment of the group identifies low trust levels, it is important to address this issue and establish trust early in your work.

Complete the Wikiversity course Earning Trust. Ask other group members to complete the course. Work to become trustworthy.

Transcend Conflicts

Conflicts among group members will greatly discourage creativity (toward the task) and productivity. If conflicts are prevalent in the group, it is important resolve them early in the work.

Complete the Wikiversity course Transcending Conflict. Work to transcend latent conflicts that continue to simmer or new conflicts that emerge in the group.

Practice Dialogue

If group member communications are typically competitive and oriented toward winning the argument rather than gaining insight, then the team needs to practice dialogue more often.

Complete the Wikiversity course on practicing dialogue. Practice dialogue.

Find courage

Openness, trust, taking risks, and even playfulness requires courage. If fears are inhibiting your curiosity, openness, ability to trust others or be trusted, risk taking, and enjoyment of play, then it will be helpful for you to find your courage.

Complete the Wikiversity course on Finding courage. Find your courage and become more open, trusting, and playful.

Emotional Competency

The skills to recognize, interpret, and respond constructively to emotions in yourself and others are key to unleashing creativity in yourself, and when working with others.

Complete the Wikiversity courses on Emotional Competency. Become emotionally competent.

Candor

Knowing when to listen, how to listen, when to speak, and what to say are key skills for unleashing creativity.

Complete the Wikiversity course on candor. Speak with candor to move the conversation toward identified goals.

In-Out Listening

Humans naturally listen at a faster rate than people normally talk. Because of this speed mismatch, the listener’s mind often wanders away from what the speaker is saying. To make constructive use of the listener’s greater capacity, Synectics recommends[11] “listening to associate” using a note-taking pad split vertically. The left-hand column of the pad is used to record information based on what you are hearing, and the right-hand column of the pad is used to record thoughts that are triggered in your mind, regardless of how random those connections might be. When the speaker finishes, the listener uses judgement, based on the openness of the climate, to decide what to share and how to share it.

Constructive Questions

People have a wide variety of reasons for asking questions. Some of these reasons are constructive, and many are destructive. Destructive reasons include gaining airtime, trying to trip up the speaker, demonstrating you know more that the speaker, redirecting the discussion, surreptitiously introducing your agenda, retribution, or some other unhelpful reason. Because we are usually aware of these manipulations, the speaker may respond defensively to questions. Questions that stop the flow of ideas, make people defensive, or create a climate where it is risky to suggest new ideas restrict the communications and may reduce idea support, risk taking, and trust. Therefore, it is helpful to only ask questions that help to move the speaker’s goals forward, and to declare your true purpose for asking the question.[12]

When you ask a question, ask only one and wait until that question is answered before asking another.

Suspending Judgement

The ability to suspend judgement is essential to the success of brainstorming, lateral thinking, and other Creative Problem-Solving techniques.

Suspending judgment is a conscious decision to withhold judgments, particularly in drawing moral or ethical conclusions, until all the facts are available. The opposite of suspending judgment is premature judgment, usually shortened to prejudice. In some philosophical systems the opposite is dogma. While prejudgment involves drawing a conclusion or making a judgment before having the information relevant to such a judgment, suspending judgment involves waiting for all the facts before deciding.

The typical process of suspending judgement can be enhanced by:[13]

- Suspending judgment as the problem is being described. Accept the problem owner’s description of the problem without challenging or questioning.

- Expressing alternative perceptions of the problem without challenge.

- Listening for ideas by paying attention to thoughts and images that may seem irrelevant but provide clues to new ideas.

- Actively encouraging absurd ideas, recalling that Einstein said “If at first the idea is not absurd, then there is no hope for it.”[14]

Idea Development

The Synetics founders observed that many ideas created in brainstorming sessions, or that arose in ideation meetings were lost because they were never understood, or never developed. They introduced the following approach to getting more out of the ideas generated:[15]

- Insist the problem owner or client own idea selection during brainstorming sessions or other idea generating activities. This overcomes the “not invented here” problem that often inhibits many good ideas from being embraced by people or organizations who could benefit from them. The team recognizes that opinions are not relevant unless they are requested by the client.

- The problem owner, typically the client, is expected to check his or her understanding of the idea by discussing it with the idea originator before evaluating the idea.

- The idea must be well understood before identifying important shortcomings.

- Ideas are evaluated in stages:

- Select ideas for newness and appeal.

- Build on the nascent idea to create a more fully formed idea. (Allow appealing half-baked ideas to become fully baked.)

- Evaluate the idea with an open mind, first emphasizing the benefits and potential before identifying important shortcomings.

- Modify the idea to overcome shortcomings and create more opportunities and greater benefits.

- Use the developed idea to support some new course of action.

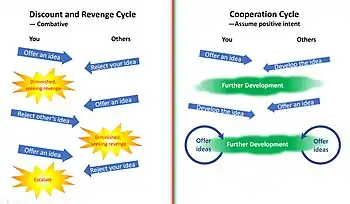

Cooperation Cycle

Unfortunately, some form of discount and revenge cycle poisons the climate in many organizations. This destructive cycle works generally like this:[16]

- Someone offers an idea

- Someone else rejects the idea.

- The idea originator gets upset, seeks revenge, and waits for an opportunity to get even.

- The person who rejected the original idea now offers his or her idea.

- The first (and now scorned) idea originator rejects this new idea out of spite.

- All ideas now go down in flames, tensions increase, retaliation becomes the norm, and the negativity escalates.

This destructive cycle can be broken by creating a cooperation cycle where offers and ideas are always treated respectfully.

- Assume positive intent.

- An idea is offered.

- The group uses the idea development techniques described above to develop the idea.

- If difficulties arise, assume positive intent and continue forward.

- As the first idea is being developed, other ideas arise.

- This new idea is also developed. This may contribute to developing the first idea or it may launch the group in a new and more fruitful direction.

- As this new idea is developed, more and more ideas arise, these contribute to the idea development, and creativity is unleased in a constructive climate.

Assignment

- Study the climate assessment conducted in the earlier assignment.

- Identify weak dimensions existing in your creative climate.

- Identify techniques, from those listed above, that can address and ameliorate identified weakness present in your creative climate.

- Use those techniques to improve the creative climate.

Summary and Conclusions

Organizational climate factors greatly influence creative results. Research has identified several organizational climate factors that encourage or discourage creative problem solving. These factors have been described and can be measured. Various techniques are available for improving the creative climate and encouraging creativity and innovation.

Improving the creative climate can unleash the latent creativity of each participant and allow a collective creativity to emerge.

Recommended Reading

Students wanting to learn more about unleashing creativity may be interested in reading the following books:

- Nolan, Vincent; Williams, Connie (2010). Imagine That! Celebrating 50 years of Synctics. Synecticsworld. ISBN 9780615413778.

- Cameron, Julia (October 25, 2016). The Artist's Way. TarcherPerigee. p. 272. ISBN 978-0143129257.

- Kettler, Todd; Lamb, Kristen N.; Mullet, Dianna R. (December 1, 2018). Developing Creativity in the Classroom. Prufrock Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-1618218049.

- Stone Zander, Rosamund; Zander, Benjamin (224). The Art of Possibility: Transforming Professional and Personal Life. Penguin. p. 224. ISBN 978-0142001103.

- De Bono, Edward (February 24, 2015). Lateral Thinking: Creativity Step by Step. Harper Colophon. p. 300. ISBN 978-0060903251.

- De Bono, Edward (August 18, 1999). Six Thinking Hats. p. 192. ISBN 978-0316178310.

- Plucker, Jonathan (September 1, 2016). Creativity and Innovation: Theory, Research, and Practice. Prufrock Press. p. 400. ISBN 978-1618215956.

- Fisher, Roger (June 1, 1988). Getting Together: Building a Relationship That Gets to Yes. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 216. ISBN 978-0395470992.

- Covey, Stephen M .R. (February 5, 2008). The SPEED of TRUST: The One Thing That Changes Everything. FREE PRESS. p. 354. ISBN 978-1416549000.

- Brown, Stuart; Vaughan, Christopher (April 6, 2010). Play: How it Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul. Avery. p. 240. ISBN 978-1583333785.

I have not yet read the following books, but they seem interesting and relevant. They are listed here to invite further research.

- Moonshot: What Landing a Man on the Moon Teaches Us About Collaboration, Creativity, and the Mind-set for Success, by Richard Wiseman

References

- ↑ 5 Reasons Why Everyone Is Creative, by Joe Giordano, Synecticsworld.

- ↑ A glossary of terms for the situational outlook questionnaire, a technical resource, by Scott G. Isaksen, Göran Ekvall

- ↑ Ekvall, G. (1996). Organizational climate for creativity and innovation. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5 (1), 105-123

- ↑ These dimensions have subsequently been studied and characterized by several researchers. See, for example Creative Climate: A leadership Lever for Innovation, by Scott G. Isaksen and Hans J Akkermans, Journal of Creative Behavior, Volume 45, Number 3, Third Quarter 2011. Also see “Creating a Creative Climate”, Creating Minds accessed June 23, 2019.

- ↑ Although the term used in the original paper is “debate” I choose to describe this as “deliberation” to emphasize the cooperative interplay of ideas rather than the competitive clashing of personalities.

- ↑ Creative Climate, Internal Conditions for Creative Behavior & Performance., OnmiSkills, LLC.

- ↑ The Situational Outlook Questionnaire.

- ↑ The Synectics Innovative Team Index.

- ↑ The Synectics Climate, by Vincent Nolan. Nolan, Vincent; Williams, Connie (2010). Imagine That! Celebrating 50 years of Synctics. Synecticsworld. ISBN 9780615413778. @151 of 818

- ↑ Covey, Stephen M .R. (February 5, 2008). The SPEED of TRUST: The One Thing That Changes Everything. FREE PRESS. p. 354. ISBN 978-1416549000.

- ↑ A visual Overview of the Synectics Invention Model, adapted by Vincent Nolan and Connie Williams. Nolan, Vincent; Williams, Connie (2010). Imagine That! Celebrating 50 years of Synctics. Synecticsworld. ISBN 9780615413778. @109 of 818

- ↑ The Synectics Climate, by Vincent Nolan. Nolan, Vincent; Williams, Connie (2010). Imagine That! Celebrating 50 years of Synctics. Synecticsworld. ISBN 9780615413778. @151 of 818

- ↑ Synectics as a Creative Problem Solving (CPS) System, Vincent Nolan. Nolan, Vincent; Williams, Connie (2010). Imagine That! Celebrating 50 years of Synctics. Synecticsworld. ISBN 9780615413778.

- ↑ Although this is often attributed to Einstein, I am not aware of any reliable source for this. See: https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Talk:Albert_Einstein#Unsourced_and_dubious/overly_modern_sources

- ↑ Synectics as a Creative Problem Solving (CPS) System, by Vincent Nolan. Nolan, Vincent; Williams, Connie (2010). Imagine That! Celebrating 50 years of Synctics. Synecticsworld. ISBN 9780615413778. @47 of 818

- ↑ Smile and the World Smiles with You, by Dr. David Walker. Nolan, Vincent; Williams, Connie (2010). Imagine That! Celebrating 50 years of Synctics. Synecticsworld. ISBN 9780615413778. @156 of 818.