Why do we find feces so disgusting?

Overview

Fecal disgust is experiencing the emotional feeling of disgust when exposed to the sight, taste, smell or even the thought of feces. According to the parasite avoidance theory, fecal disgust is an important emotion that has been attributed to the survival of the human race as it deters people from exposure to harmful contaminants that are found within feces (Curtis, de Barra & Aunger, 2011). Despite the importance of fecal disgust for survival, it can also provide barriers to the wellbeing of the self and the community. These barriers include becoming too hygienic (Tolin, Woods & Abramowitz, 2006), refusing important medical investigations and treatments (Reynolds, Bissett & Consedine, 2018), as well as impairing moral judgement (Schnall, Haidt, Clore & Jordan, 2008). Understanding implications and the nature of fecal disgust may help individuals make informed choices when presented with these barriers.

Why are we disgusted by feces?

Most people don’t need a reason to be disgusted by feces and probably don’t care to think about why either. Instead, some may wonder why animals aren’t disgusted by feces as they watch their dog eat an old dried up stool on the lawn. It is common knowledge that animals tolerate feces better than humans. For example, no one has yet reported animals displaying extreme emotional reactions such as dramatically dry reaching, screaming, and using hand sanitizers excessively when presented with an unknown stool. So why do humans exhibit such strong feelings of disgust towards feces? To find an answer it is important to look at the underlying theories surrounding disgust and behaviour.

What is disgust?

Disgust is a negative emotion which is often felt as a response to being exposed to a disturbing stimulus such as feces, wounds, blood, corpses, insects, diseased animals or people, and spoilt food (Darwin, 1872). Feelings of disgust may also occur towards others' behaviour, lifestyle choices and values (Schnall, Haidt, Clore & Jordan, 2008). Depending on the stimulus, feeling disgusted may urge one to avoid the disturbing stimulus by activating behavioural, physiological and psychological changes. These changes can include nausea, disinterest, fear, avoidance or hostility (Darwin, 1872).

Most researchers agree that is disgust is a unique emotion that is experienced universally (Ekman, 2016). Paul Ekman and Wallace Friesen (1972) first expanded on the work of Charles Darwin in The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals; which hypothesised the universality of emotional expression in humans as evolved traits. Ekman and Friesen identified six basic emotions; anger, sadness, happiness, disgust, anger and surprise which were identifiable by all members of an isolated tribe in Papua New Guinea (Ekman & Friesen, 1971). Disgust is also included in many other recognized theories of emotions such as Robert Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions (1980) and Parrott’s Classification of Emotions (2001).

Disgust and parasite avoidance

Disgust is a response to disturbing stimuli that is believed to be an important part of survival for both animals and humans. Disturbing stimuli such as feces, rotting carcasses etc… are likely to be infested with parasites and diseases. Feeling disgusted therefore encourages one to avoid contact with the disturbing stimulus in order to prevent infections and diseases which can be detrimental to one’s survival (Curtis, de Barra & Aunger, 2011).

Disgust sensitivity can vary between and within different species. Humans tend to be more sensitive to disgust compared to animals especially in terms of fecal matter, but that doesn’t mean animals aren’t disgusted by feces. Several studies have found that most animals find feces disgusting, which is attributed to parasitic avoidance. Grazing animals such as sheep, deer, cows etc... will avoid grazing in fields or patches where fecal matter is abundant (Hutchings, Judge, Gordon, Athanasiadou & Kyriazakis, 2006). Primates also avoid eating foods contaminated with feces despite using their fecal matter to offend their opponent (Poirotte, Massol, Herbert, Willaume, Bomo, Kappeler, & Charpentier, 2017).

Avoiding parasitic infection and diseases can also have its consequences. For example, animals that go to lengths to avoid parasites may expose themselves to predators resulting in a more imminent threat (Buck, Weinstein & Young, 2018). People that go to lengths to avoid parasitic infection through contact with feces may also experience consequences such as extreme hygiene rituals as a symptom of obsessive-compulsive disorder (Tolin, Woods & Abramowitz, 2006), avoiding public areas such as hospitals and bathrooms, and avoiding socializing with others (social isolation).

Theories of learning and behaviour

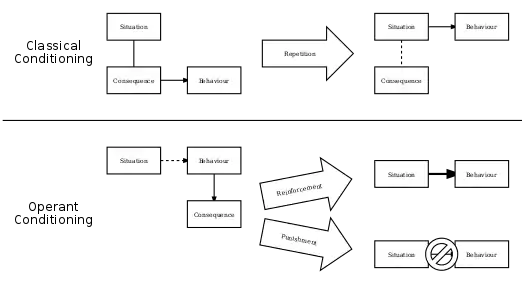

Fecal disgust sensitivity levels may have been something that was taught to us either by reinforcement or by observing others. Therefore, how we respond to feelings of disgust can be attributed to the principles of learning. Learning falls within the realm of behaviourism and is often studied by behavioural psychologists. Several important learning theories are observational learning, operant conditioning and classical conditioning. Below, these three theories will be applied to a hypothetical scenario involving children to demonstrate the development of fecal disgust sensitivity levels.

Observational learning

Observational learning is derived from Social Learning Theory and implies that one learns by observing others. Observational learning is especially significant in children and insists that learning will occur when the behaviour is presented by a role model such as a parent, sibling, friend, teacher or idol. Conditions for observational learning include: attention; individuals must relate to the model and show interest in their behaviour, retention; individuals must be able to memorize the behaviour, motivation; individuals need to feel motivated to imitate the behaviour (survival, positive/negative affect), and reproduction; individuals must be capable to imitate the behaviour (Stone, 2018). This theory was put to the test in a famous experiment conducted by Albert Bandura (1961) suggesting that children will imitate aggressive behaviour towards the Bobo Doll that was demonstrated by adult models (Bandura, Ross & Ross, 1961).

Observational learning theory applied to fecal disgust sensitivity levels implies that a child may have witnessed someone they consider to be a role model - such as their mother - react quite dramatically when exposed to fecal matter. Perhaps she went to pick up some dog stool from the lawn and started screaming when some got on her hand. In turn, the child has adopted this behaviour and now reacts this way too. This can also spread by observing the behaviour of peers, therefore this child could potentially go to school and behave this way influencing other children to adopt this reaction to fecal matter.

Operant conditioning

Operant conditioning is a learning theory proposed by B. F. Skinner based on Thorndike’s Law of Effect. Operant conditioning assumes that learning occurs when overt (observable) behaviours are reinforced by either reward or punishment (Skinner, 1938). Skinner would observe animal’s reactions to reinforcements and noticed changes in behaviour when presented with both rewards and punishments. Rewards (promoting behaviour) were shown to be more effective than punishments (deterring behaviour) in the long term however, punishments promoted fear in the animals (Skinner, 1953).

Operant conditioning principles applied to fecal disgust sensitivity levels could imply that a child went to investigate or play with some dog stool in their backyard. However, each time they made contact with the dog stool a parent or guardian may have yelled at them or spanked them (punishments) to teach them not to engage in that behaviour. Depending on the nature of the child and the severity of the punishment – the child may probably become more sensitive to disgust regarding fecal matter due to fear. This child may too influence their peers if they scold classmates for making contact with fecal matter.

Classical conditioning

Classical conditioning (Pavlovian Conditioning) is often considered to play an important role in the development of fears, phobias, and other anxiety disorders (Schienle, Stark & Vaitl, 2001). The classical conditioning theory suggests that when individuals associate the conditioned stimulus; a previously neutral stimulus (making contact with fecal matter) with the unconditioned stimulus (the idea that one will be contaminated with parasites and diseases) will eventually trigger a new conditioned response which can include fear, anxiety and a fecal specific phobia such as Coprophobia (Shechner, Hong, Britton, Pine & Fox, 2014). The Classical Conditioning Theory believes that one may eventually reverse conditioned emotional responses through a method called extinction which involves repeatedly presenting a conditioned stimulus (feces) without the unconditioned stimulus (contracting a deadly parasite) (Follette & Dalto, 2015).

Classical conditioning principles applied to fecal disgust could imply a child that has decided to play with a dog stool on the lawn. The role model such as the mother may notice this and explain in a disgusted tone that feces is really gross and if they touch the dog stool they will contract a disease and die. This may happen several times before the child starts to adopt high sensitivity towards disgust and associate feces with disease and dying.

Benefits of fecal disgust

The list of benefits regarding fecal disgust is small yet significant. Benefits include: avoiding parasites and diseases, keeping up with good hygiene practices that makes one smell nice and look fresh, and not belonging to the very rare cohort of individuals that feel sexual gratification and/or arousal derived from the smell, taste, or sight of feces or from the act of defecation. This paraphilic behaviour is called Coprophilia (Gale, 2007).

Consequences of fecal disgust

Compared to the benefit of avoiding parasites and diseases, there are strangely far more consequences of fecal disgust than one might imagine. Interestingly, these consequences all impact one’s own health and wellbeing and the wellbeing of humanity as a community.

Negative obsessions

Being overly concerned with hygiene and fearing contamination can eventually turn into obsessions, extreme fear or anxiety in some individuals. Disgust sensitivity can trigger several anxiety disorders such as obsessive-compulsive disorder or a specific fecal phobia such as Coprophobia (Muris, 2006). Although the severity of each disorder varies between people, most will describe their symptoms to affect their personal and professional lives. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is marked by intrusive thoughts (obsessions) that appear real despite being able to understand that they are absurd. Suffers feel they need to perform rituals (known as compulsions) in order to avoid the outcome of their intrusive thoughts. They may also constantly ask for reassurance. In terms of fecal disgust, fecal commination may be the focus for the sufferers of OCD (the obsession) where they may feel they have to constantly wash their hands to prevent contamination (Tolin, Woods & Abramowitz, 2006). Specific fecal phobia (Coprophobia) is marked by extreme fear of fecal matter. Most will avoid making contact with fecal matter at all costs with some even refusing to leave the house (Medicine.Net, 2018).

Treatments for both of these anxiety disorders includes Exposure Therapy and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy where sufferers are exposed to fecal matter in a safe environment and their limiting beliefs are challenged (Craske, Treanor, Conway, Zbozinek & Vervliet, 2014).

Avoiding medical treatments and interventions

Fecal disgust can also endanger one’s life if an individual is too embarrassed to see a doctor or participate in tests that involve providing a stool sample or having a colonoscopy. It can also prevent one form receiving treatments such as fecal transplants and colon or rectal surgeries. As early detection is the key to overcoming most medical issues, avoidance due to fecal disgust can mean someone’s serious medical illness can go untreated. Researchers looking into emotions that encourage avoidance of screening and treatment found that fecal disgust does contribute to the avoidance of screening and treatment of colorectal cancer as well as fear and embarrassment (Reynolds, Consedine, Pizarro & Bissett, 2013; Reynolds, Bissett, & Consedine, 2018). They also propose mindfulness and exposure therapies as effective methods to treat screening and medical treatment avoidance as a result of disgust.

Impaired moral judgement

Research has shown that people are less likely to help others if they feel disgusted by them (Winterich, Mittal & Morales, 2014) and that people are more disgusted by poor people than by the poverty the poor are forced to live in (Moore, 2012). People living in poverty often are unable to regularly access a shower, clean clothes and toilet paper. In turn they may appear to be unkept, dirty and smell like feces. Most people find unhygienic people disgusting and fear contamination while near them. As a result, some treat unhygienic people with hostility and avoid them (Schnall, Haidt, Clore & Jordan, 2008). Despite the advancement of the human race with the development of morals and cognitive reasoning, the power of disgust continues to interfere with our moral judgements leading to the engagement of self-interested behaviours that are unethical (Schnall, Haidt, Clore & Jordan, 2008; Winterich, Mittal & Morales, 2014). This does not necessarily mean that people are inherently mean or snobby since disgust and avoidance is a natural survival instinct as suggested by the parasite avoidance theory (Curtis, de Barra & Aunger, 2011). This just means that people are focused on their own survival and the survival of their own "pack". However, acting on animalistic instinct is not an excuse to ignore suffering.

How to overcome consequences of fecal disgust

The best solution for fecal disgust sensitivity is to first recognize how severely it is affecting your quality of life. Usually if the consequences are on the milder end of the spectrum you may be able to practice mindfulness in order to identify if the risk of contamination is truly threatening to your life (Sato & Sugiura, 2014). Mindfulness is the act of being present in the moment in order to challenge cognitive biases and beliefs.

When dealing with the more severe consequences of fecal disgust sensitivity you may be struggling with limiting or false beliefs that impair your judgments. Therapies that have proven to be effective in these circumstances are Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Exposure Therapy (Craske, Treanor, Conway, Zbozinek & Vervliet, 2014; Kubany & Manke, 1995). If you feel that the consequences are on the more severe end of the spectrum it is beneficial to speak with your GP about the issue so they can recommend you to a counsellor or a psychologist for further assistance. In some cases, you may also be prescribed some medication while you undertake therapy.

Conclusion

Fecal disgust is a basic emotion experienced by some animals and most humans which is important for avoiding parasites, bacteria and diseases that may jeopardize one’s survival. Levels of fecal disgust may vary between people and are often taught to us at a young age either through principles of observational learning, operant conditioning and/or classical conditioning. The benefits of fecal disgust are much shorter than the consequences and include avoiding contamination of parasites, bacteria and diseases as well as keeping up with good hygiene practice. Consequences of fecal disgust include; negative obsessions and false beliefs that can lead to anxiety disorders such as Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder or fecal specific phobia (Coprophobia), avoiding medical screening and treatments which can prevent early intervention to serious illnesses such as colorectal cancer, and impaired moral judgement that affect the global community as people are less likely to help others they find disgusting. Overcoming consequences of disgust usually involves being mindful and assessing the risks against the benefits as well as speaking to your GP to be referred to a professional that can administer Cognitive Behavioural Therapy or Exposure Therapy.

Quiz

Can you ace this quiz? To find out choose the correct answers and click "Submit":

For more information, see Help:Quiz.

See also

Anxiety

Digestive system and emotion

Disgust

Disgust and prejudice

Fear as a motivator

Paraphilia motivations

References

Buck, J., Weinstein, S., & Young, H. (2018). Ecological and Evolutionary Consequences of Parasite Avoidance. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 33(8), 619-632. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2018.05.001

Craske, M., Treanor, M., Conway, C., Zbozinek, T., & Vervliet, B. (2014). Maximizing exposure therapy: An inhibitory learning approach. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 58, 10-23. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.006

Curtis, V., Aunger, R., & Rabie, T. (2004). Evidence that disgust evolved to protect from risk of disease. Proceedings of The Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 271(Suppl_4), S131-S133. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2003.0144

Curtis, V., de Barra, M., & Aunger, R. (2011). Disgust as an adaptive system for disease avoidance behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1563), 389-401. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0117

Darwin, C. (1872). The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. United Kingdom:

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. (1971). Constants across cultures in the face and emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 17, 124-129.

Follette, W., & Dalto, G. (2015). Classical Conditioning Methods in Psychotherapy. International Encyclopedia of The Social & Behavioral Sciences, 764-770. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-08-097086-8.21052-0

Gale, T. (2007). Coprophilia | Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved from https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/coprophilia

Hutchings, M., Judge, J., Gordon, I., Athanasiadou, S., & Kyriazakis, I. (2006). Use of trade-off theory to advance understanding of herbivore-parasite interactions. Mammal Review, 36(1), 1-16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2907.2006.00080.x

Kubany, E., & Manke, F. (1995). Cognitive therapy for trauma-related guilt: Conceptual bases and treatment outlines. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 2(1), 27-61. doi: 10.1016/s1077-7229(05)80004-5

Medicine.Net (2018). Definition of Coprophobia. Retrieved from https://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=12211

Moore, S. (2012). Instead of being disgusted by poverty, we are disgusted by poor people themselves | Suzanne Moore. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/feb/16/suzanne-moore-disgusted-by-poor

Muris, P. (2006). The pathogenesis of childhood anxiety disorders: Considerations from a developmental psychopathology perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30(1), 5-11. doi: 10.1177/0165025406059967

Parrott, W. Gerrod (2001). Emotions in social psychology: essential readings. Psychology Press, Philadelphia, Pa.; Hove Plutchik R (1980). A Psycho-evolutionary Synthesi. New York: Harper and Row.

Poirotte, C., Massol, F., Herbert, A., Willaume, E., Bomo, P., Kappeler, P., & Charpentier, M. (2017). Mandrills use olfaction to socially avoid parasitized conspecifics. Science Advances, 3(4), e1601721. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1601721

Reynolds, L., Consedine, N., Pizarro, D., & Bissett, I. (2013). Disgust and Behavioral Avoidance in Colorectal Cancer Screening and Treatment. Cancer Nursing, 36(2), 122-130. doi: 10.1097/ncc.0b013e31826a4b1b

Reynolds, L., Bissett, I., & Consedine, N. (2018). Emotional predictors of bowel screening: the avoidance-promoting role of fear, embarrassment, and disgust. BMC Cancer, 18(1). doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4423-5

Sato, A., & Sugiura, Y. (2014). Dispositional mindfulness modulates automatic transference of disgust into moral judgment. The Japanese Journal of Psychology, 84(6), 605-611. doi: 10.4992/jjpsy.84.605

Schienle, A., Stark, R., & Vaitl, D. (2001). Evaluative Conditioning: A Possible Explanation for the Acquisition of Disgust Responses. Learning and Motivation, 32(1), 65-83. doi: 10.1006/lmot.2000.1067

Shechner, T., Hong, M., Britton, J., Pine, D., & Fox, N. (2014). Fear conditioning and extinction across development: Evidence from human studies and animal models. Biological Psychology, 100, 1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.04.001

Schnall, S., Haidt, J., Clore, G., & Jordan, A. (2008). Disgust as Embodied Moral Judgment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(8), 1096-1109. doi: 10.1177/0146167208317771

Skinner, B. (1938). The Behaviour of Organisms. New York: D. Appleton-Century Company, INC.

Skinner, B. (1953). Science and Human Behaviour. The University of Michigan: Macmillan.

Stone, S. (2018). Observational learning | psychology. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/science/observational-learning

Tolin, D., Woods, C., & Abramowitz, J. (2006). Disgust sensitivity and obsessive–compulsive symptoms in a non-clinical sample. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 37(1), 30-40. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2005.09.003

Winterich, K., Mittal, V., & Morales, A. (2014). Protect thyself: How affective self-protection increases self-interested, unethical behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 125(2), 151-161. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.07.004

External links

The Strange Politics of Disgust (TED Talks, Youtube, 14:02 mins)

The Yuck Factor: The Surprising Power of Disgust (Alison George, New Scientist, 2500 words approx)

Why Do We Like Our Own Farts? (AsapSCIENCE, Youtube, 2:55 mins)