Motivation, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder

| This page is part of the Motivation and emotion textbook. See also: Guidelines. |

| Completion status: this resource is considered to be complete. |

Motivation and Anxiety Disorders

Are we living in the Age of Anxiety?

Today’s society is becoming faster paced and more pressured than ever before. Technology is on the rise, mobile phones are increasing in capability and various media outlets are constantly updating and highlighting daily horror stories and health concerns. People are continually faced with societal expectations to stay looking young, achieve successful careers and maintain high levels of social status. With these ongoing external demands and pressures, an evolving environment and self-imposed internal stresses, it could be questioned the extent to which these elements take part in the development of anxiety disorders and motivate the associated behaviours. Anxiety disorders are becoming more and more common within society, with sufferers running to their local GP’s in hope of prescription drug treatments as a quick solution. Many Australians may be faced with the ongoing struggle associated with the diagnosis of an anxiety related condition. This warrants the need to truly enhance the current medical and academic communities understanding of the motivating factors behind these disorders and the consequences associated with these illnesses. While mental health campaigns continue to highlight the increasing incidence and symptoms of anxiety, many questions surrounding anxiety behaviour motivation remain unanswered.

- Are anxiety disorders really mental illnesses or are they just learned patterns of behaviours and cognitive scripts formed through experience?

- Are anxious behaviours the result of the internal biological components within the brain or are they just exaggerated survival mechanisms passed down through evolution?

- Does the media’s promotion of mental illnesses really assist in the understanding and treatment or does it only reinforce and give rise to fears and social stigma amplifying such conditions?

Motivational psychologists primary goal understanding anxiety disorders is to determine the root cause of anxiety driven behaviour and provide a rational for an individual’s engagement and intensity of conduct.

What is Motivation?

The study of motivation concerns processes whereby behavior can be explained in terms of energy and direction. Energy is identified as the arousal aspect,the inner drive or force whereby someone is driven to carry out some form of behavior. However, energy alone is not enough for the behavior to occur. Direction such as a desired outcome or goal is required in combination with arousal for activity to occur.

Motivation revolves around seeking solutions to two main questions.

- What causes behaviour ?

- Why does behaviour vary with intensity ?

In order to understand the motivating factors driving an anxiety disorder, many theoretical components need to be considered. An anxiety disorder involves many behaviours depending on the type of disorder examined (Cisler, Olatunji, Lohr & Williams, 2009). For the purpose of this chapter, the focus is on Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD). This is largely because the disorder is extremely complicated, often misunderstood by the public and in some cases treatment involving medications does not always provide releif (Barrett,Farrell,Pina,& Piacentini, 2008). OCD is driven by many factors including biological, cognitive and learning (Starcevic & Berle, 2008). OCD can have devastating effects on the individual, especially if they don't have good coping skills and a reasonable understanding of their condition (Barrett et al., 2008). While this chapter does not cover treatment, it does attempt to explain the motivational aspects underlying the condition.

Motivational Questions & OCD

To gather a complete understanding of the role motivation plays in the expression of OCD symptoms, the following questions need to be taken into consideration.

- What initiates obsessions to enter consciousness?

- Why does the content regarding these obsessions vary between OCD individuals?

- What causes an OCD sufferer to engage in compulsive behaviour?

- What sustains the disorder over time?

- Why do OCD individuals vary in the intensity of compulsive behaviour?

- What signals the OCD individual to stop the compulsive behaviour?

What are Anxiety Disorders?

The term anxiety disorder covers a large range of anxiety related conditions (Lang, & Mcteague, 2009). Individuals who suffer from these conditions generally report emotions or symptoms of excessive fear, inappropriate thoughts, hyper-vigilant states, and an overwhelming feeling that they may lose self-control (Starcevic & Berle, 2006). The cluster of anxiety disorders can be broken down into Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD), Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Social Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder, Agoraphobia and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (Starcevic & Berle, 2006). While these conditions are distinguished separately with individual diagnosis and different theoretical models, many have overlapping symptoms which can severely impact an individuals’ life (Hewitt, Egan, & Rees, 2009). It’s likely if an individual has one of these disorders, they may also meet the diagnostic criteria for another. For instance individuals who suffer from social phobia, are also likely to meet the criteria for panic disorder (Starcevic & Berle, 2006).

What is Obsessive Compulsive Disorder?

Obsessions can be identified as persistent, bothersome, intrusive, inappropriate thoughts and impulses, often leading the individual to experience high levels or stress and anxiety (O'Connor, 2007). A sufferer’s thoughts often arise in consciousness containing themes of violence, sex, health and religious. While the sufferer may be convinced they are losing their mind or developing a psychotic illness, the opposite is very true. The individual is very aware of the bizarre content and knows that these obsessions are purely a product of his or her mind (O'Connor, 2007).

Compulsions can be defined by repetitive mental acts (counting, praying, saying affirmations silently) or excessive behavioural actions (checking locks, hand washing, seeking reassurance and cleaning). Individuals carry out the compulsive acts following an obsession in an attempt to relieve the anxiety experienced (Reuven-Margil, Darr & Liberman, 2008). While the general public may be familiar with OCD behaviours such as excessive cleaning, fewer are aware of the internal obsessions and the bizarre content which motivate these compulsive acts. Due to the consequences of social stigma and embarrassment that is often attached to the individual, it is suggested many sufferers withhold the content of their intrusive thoughts and choose not to seek help. This can further exacerbate the condition, causing the individual to withdraw and leaving them a prisoner within their own mind. However, researchers suggest that suffers of OCD usually demonstrate high levels of intelligence. The motivating factors behind OCD are generally the same influences which drive the individual to obtain high levels of success. An OCD sufferer is more likely to succeed if he/she is not restricted by societal routine, but rather follow their individual intrinsic goals and passions (Deci & Ryan, 2008).

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder diagnosis can be considered when an individual suffers either repetitive obsessions or obsessions combined with compulsions which are ongoing, worrisome and time consuming over an extended period of time and impacting ones well being (Lang, & Mcteague, 2009).

Below is an example of someone suffering from OCD.

Jeremy had been battling obsessions for years. One ongoing obsession he had was an intense fear of the number seven. Jeremy thought that if he saw the number seven he or one of his family members would get cancer. Jeremy knew this made no logical sense. However, every time he saw a number seven, an anxious feeling swept over him and he would silently pray to God that nothing bad would happen. Over time this obsession became worse and worse, consuming much of his time and damaging his self-esteem. He started to develop panic attacks at the mere sight of anything that resembled a seven. He stopped going to movie cinemas because of the showing times on the board, he stopped driving past streets where he knew he would see a seven and eventually threw away every clock in house because it had a number seven on it. Jeremy was constantly on guard, hyper-vigilant and lost all his self-belief.

Theory and Research

Theories of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

The theories developed by Pavlov, Skinner and Bandura are based on learning principles such as fear conditioning, operant conditioning, reinforcement and social learning (Starcevic & Berle, 2006). These theories have provided tremendous insight into explaining the motivation behind anxiety disorders. Learning theories are particularly helpful in explaining how social phobia and agoraphobia are developed and sustained (Starcevic & Berle, 2006). However, due to the complexity of human behaviours, particular those expressed in OCD, alternative theories must also be examined. Learning theories simply can’t provide a comprehensive explanation as to why an individual experiences constant intrusive thoughts surrounding religious, violent, sexual and health content (Moulding, Kyrios, Doron, & Nedeljkovic, 2009). These thoughts are generally inconsistent with the individuals’ personality traits. Evolutionary, biological and cognitive theories also play vital roles (Londsorf, Weike, Nikamo, Shalling, Hamm & Oham, 2009).

The underlying factors of all anxiety disorders which result in heighten states of fear, are suggested to be the result of evolved brain circuitry, chemical neurotransmitter imbalances, overactivity or malfunctioning brain structures, memory encoding of negative past events, as well as cognitive beliefs (Starcevic et al., 2006).

Evolutionary Theory

Evolutionary theory suggests that motive circuits within the brain evolved over time because they were necessary for survival. Research has suggested that emotions reflect the activation of the appetitive motive system and the defensive motive system (Lang & McTeague, 2009). The appetitive motive system directs and guides behaviours that ensure the basic needs are met such as procreation, hunger and thirst. Alternately, the defensive motive system directs and guides behaviours to ensure safety in response to environmental threats (Lang & McTeague, 2009). When an individual suffering from OCD experiences an intrusive thought, it is suggested that the defensive motive system is activated, directing and guiding the individual towards avoidance type behaviours (Lang & McTeague, 2009). These avoidance behaviours include avoiding places, people and specific objects or any external stimuli that may produce a feeling of fear (Lee, Lim, Lee, Kim, & Choi, 2009).

From the example involving Jeremy, we can see that the defensive system was activated every time his sensory systems within the brain recognised the number seven. This recognition, to Jeremy, signalled danger. Evolutionary theory suggests this form of reactive behaviour stems from an individual’s core goal of survival. This survival instinct is passed down from our ancestors.

Recent research has found that certain genes may act as motivators towards the development OCD. Londsorf, et al.,(2009) investigated the effects of two genetic polymorphisms 5-HTTLPR and COMTvall58met on conditioning and extinction of fear. The study involved 48 participants and discovered that carriers of the 5-HTTLPR factor acquired fear when exposed to environmental threatening stimuli. Furthermore, the results identified that carriers of the COMTvall58met gene have a reduced ability to turn off the fear conditioned response (Lonsdorf, et al., 2009). This suggests those genes act as motivators for OCD and even more so when the individual is a carrier of both.

Biological Component

- The Amygdala

Research in the field of neuroscience has identified that malfunctioning circuitry within the brain structures play a major role in OCD (Lang, Kroll, Lipinski, Wessa, Ridder, Christmann, Schad & Flor, 2009). Brain imaging tools show that when an individual is exposed to fear provoking stimuli, increased activity occurs within the amygdala. The amygdala functions in the storage of highly emotionally charged events, specifically those concerning fear (Lang, et al., 2009). Research suggests that when an individual is experiencing levels of high anxiety, the amygdala is highly aroused (Lee, et al., 2009). When an individual’s amygdala is constantly active overtime, the base rate at which the amygdala once operated may become reset to a higher level. This provides insight into the explanation of symptoms of hyper vigilance, fear and constant worry (Zvolensky, Forsyth, Bernestein & Leen-Feldner, 2007).

- The Worry Circuit

The orbital cortex functions as the error detection circuit. This component of the brain is responsible for stimulating pathways concerning worry (Saxena, Gorbis, Oneill, Baker, Mandelkern, Maidment, Chang, Salamon, Brody, Schwartz & London, 2009). These pathways run between the caudate nucleus, the cingulate gyrus, and the thalamus. Research suggests that the caudate nucleus is responsible for changing from one thought to another. When an individual with OCD experiences an intrusive thought, they become ‘stuck’ and are unable to move to the next thought process. The persistence of intrusive thoughts are suggested to be the result of a malfunctioning caudate nucleus (Robinson, Wu, Munne, Ashtari, Alvir, Lerner, Koreen, Cole, & Bogerts, 1995).

- The Striatum

The striatum is the key component allowing the intrusive thoughts into awareness. The striatum acts as an automatic transmission and filtering system. When the striatum isn’t functioning correctly, the sensory information coming from the external world isn’t being filtered effectively. This allows the old evolutionary circuits to pass through resulting in the intrusive thoughts (Lang, & McTeague, 2009).

- Neurotransmitters

- Serotonin - Low levels of serotonin are suggested to act as biological motivators in individuals with OCD. Research has shown that individuals suffering OCD symptoms, can improve through serotonin enhancing drugs (Barrett et al., 2008).

- Dopamine - Low levels of dopamine can result in decreased executive functioning within the brain. This can result in reduced cognitive ability.

Social Cognitive Theories

Social cognitive theories are very important in understanding how anxiety disorders such as OCD are developed and sustained. Social cognitive theory was initiated by Albert Bandura. He proposed that individuals learn through the observations of others, and that cognitive beliefs about the self contribute to future decision making, behaviour engagement or disengagement and coping strategies. Bandura developed the theory self-efficacy, suggesting that individuals will either be motivated towards or away from certain behaviours based upon their beliefs involving competence. For the purpose of this chapter both the cognitive component and learned components will be examined. Individuals suffering from OCD have certain cognitions that act as motives, guiding anxious behaviour.

Cognitive Component

The intrusive thoughts constantly experienced by OCD sufferers are suggested to be experienced by every person at some stage in their lives. They are universal in nature and are experienced by males and females of all cultures. Many cognitive models propose that individuals with OCD are different in their thought processes because they apply excessive meaning to them (Moulding et al., 2009). They misinterpret certain thoughts as an indication that something is very wrong, creating an intense feeling of fear usually accompanied by anxiety (O'Connor, 2007). For instance, if a mother were to have the thought “grab the pillow and smother the baby” she might automatically think she is a risk of hurting her child and run out of the house. She would then doubt herself and think she is a terrible person for having such a thought. Following an incident like this the mother may begin to fear having the thought again, placing greater emphasis on the meaning of the original occurrence (Reuven-Magril et al., 2008). This creates anticipatory anxiety, where the individual attempts to control the reoccurrence of such negative or violent thoughts (Reuven-Magril et al., 2008). This act is motivated from the internal need to feel safe, secure and protected both for the individual and loved ones.

The human mind is highly imaginative, especially in OCD sufferers. Their imagination may increase at times of stress causing the thoughts or obsessions to spiral out of control. An original obsession such as a fear of harming loved ones can manifest into multiple obsessions containing religious and sexual content (O'Connor, 2007). The external environment can often act as stimuli triggering intrusive thoughts and anxiety. For example, the daily news containing horror stories about new illnesses, teenage shootings and terrorism can exacerbate an OCD condition. This violent stimulus can motivate the OCD individual to display avoidance behaviours where they no longer watch TV, listen to the radio and avoid reading the newspapers (Cisler, Olatunji, Lohr, & Williams, 2009). Conversely, these obsessions can motivate the individual to engage in excessive activities such as praying for hours a day, washing their hands excessively before eating meals and constantly cleaning. Some extreme cases even report individuals driving along the highway and having an intrusion that they just ran over someone. This may cause the individual to check the environment for hours and incessantly reassure themselves that everything is OK.

The intrusions experienced by OCD individuals are different from those suffering psychotic illness. The OCD sufferer is not paranoid and is very aware of the bizarre content of their intrusions. Paranoia is a word often thrown around society in the wrong context and mistaken for anxiety. Individuals suffering from OCD know their behaviours and obsessions are not logical and do not experience delusions or hallucinations.

Researchers have found that OCD individuals generally hold several cognitive beliefs that underlie the illness (Moulding et al., 2009) These include:

- Inflated Responsibility - They think they are responsible for actions that are outside of their control - For example, “It’s my fault my parents are getting divorced”, or “It’s my fault my girlfriend cheated on me, maybe I wasn’t been a man”.

- Placing over importance on their thoughts – For example, “that persons attractive, I shouldn’t be thinking that, I am in a relationship”

- The importance of controlling ones thoughts – Thinking they must have complete control over their thoughts – For example, “I must control my thoughts or I am not a pure person and might go to hell for external punishment”

- Over estimation of threat – For example “Seven people at work got cancer, what if I get cancer or someone in my family does”

- Intolerance of uncertainty – For example “It’s unlikely I would ever a rob a liquor store, I have been alive for 20 years and I haven’t yet, but it’s still possible”

- Perfectionism – For example “The wine glasses has to be arranged perfectly and crystal clear” (Moulding et al., 2009).

These internal beliefs are unrealistic expectations and may to some extent act as goals. Ultimately when viewed from a goal orientated perspective the outcome will be disappointment. Research involving Mihaly’s work on “Flow” and “Optimal Experience” suggests that when the goal is set too high, above the skill level of the individual, the emotion anxiety is likely to be experienced. This may be another motivating factor when considering the development of OCD.

Research has investigated the effects of control related cognitions in relation to OCD (Reuven-Magril et al., 2008). The more persistent the person is in trying to neutralise the obsessions, the more likely it is that he/she has control related beliefs. This provides an explanation as to why some OCD individuals engage with greater intensity when carrying out their compulsions. The study also determined that having a low sense of control was directly related to the increased severity of OCD symptoms. Further, it has been found that OCD individuals have low perceptions of competence (Reuven-Magril et al., 2008).

The Learned Component

Pavlovian fear conditioning theory is a form of associated learning in which an original neutral stimulus develops into a conditioned stimulus (CS) after several pairings with an unconditioned threat stimulus (US). This can provide insight into some of Jeremy’s (example listed at the beginning of the chapter) compulsive behaviours. Every time Jeremy identifies the number seven in his surroundings, it acts as a conditioned stimulus that triggers fear, giving rise to anxiety. Due to this trigger, Jeremy feels compelled to ‘get rid of’ the emotion through the act of compulsive behaviour. This is goal directed in attempt to achieve an internal state of peace. The theory of operant conditioning developed by Skinner, indicates that the compulsion may act as a reinforcer. This further motivates the disorder to be sustained (Londsorf et al., 2009).

Living with OCD

Many individuals with OCD often face difficulties in ordinary daily activities. This ranges from holding onto jobs, communicating with others, developing close relationships, feeling at ease with oneself and taking risks. They can often feel very alone, helpless and suffer from constant negative emotions such as fear, shame and doubt. These negative emotions can act as motivators in themselves, leading to obsessional thinking and the repetitive cycle involving compulsive behaviour. OCD individuals often report that they feel as though the ability to live a normal life has been taken away from them. This can lead to learned self helplessness, depression and other anxiety disorders such as social phobia, agoraphobia and panic disorder. This only adds to the challenges the individual is faced with. Due to the frustration OCD causes, some individuals are motivated to take extreme actions to resolve their illness and allow them to return to a normal life. This can involve activities such as constantly researching books, medical articles and investigating the latest OCD related therapies. However, due to the theories behind operant-conditioning, this may become compulsion in itself through the act of reinforcement. This can make the disorder very difficult to treat. For the purpose of this section, living with OCD will be linked with the components of Self Determination Theory.

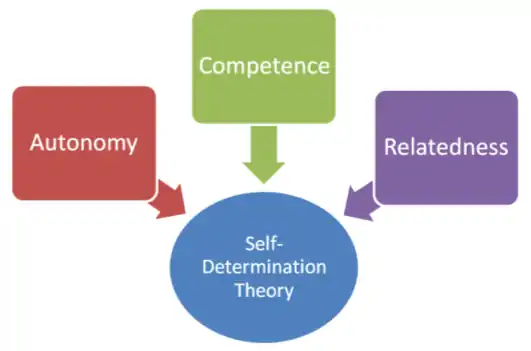

Self Determination Theory

Autonomy

Autonomy is a psychological need to make an independent decision and exert control over the external environment. Every healthy adult individual has the desire to choose their own actions and decide when, where and how these actions will take place. This freedom is a basic instinct (Deci, & Ryan, 2008). However, an OCD sufferer often feels a low sense of this basic self-sufficiency. Their intrusive thoughts or obsessions ‘take over’ and the sufferer is compelled to act out the consequent compulsion. This thought and reaction process creates a low perception of autonomy (Starcevic et al., 2006). The OCD sufferer generally has little ability to choose their actions during the obsessive state because of a heightened emotional response. Research suggests OCD sufferers often compensate for this loss of autonomy by over-controlling their actions and emotions.

Competence

Every individual strives to develop and sustain competence. Competence is a psychological need to progress in life and overcome life’s challenges. Throughout the life cycle an individual will continually attempt to interact effectively with their environment and with others, improve their skills and potential and gain competence in all possible areas (Deci, & Ryan, 2008). This is necessary for development and personal growth. An OCD sufferer however, has low competence and often finds it difficult to effectively interact with their environment (Reuven-Magril et al., 2008). They are less likely to engage in social activities and seize opportunities when they arise, due to a fear of constant anxiety or compulsive actions. This may lead to the acceptance of lower employment positions, less social support and possible isolation.

Relatedness

Every individual has the desire to be connected to others. Intimate relationships and friendships are vital to everyday functioning and provide an individual with a sense of acceptance, acknowledgement and understanding. This relatedness is highly valued and has been showed to reduce overall personal stress levels (Deci, & Ryan, 2008). However, an individual suffering with OCD may experience certain barriers to developing strong interpersonal connections and therefore a low sense of relatedness. This may be due to their anxiety and avoidance of social situations and their fear of being dismissed as ‘crazy’ (Starcevic et al., 2006). As an OCD sufferer is well aware of the bizarre nature of their thoughts and actions, they are vulnerable to social rejection and stigma.

Summary

Anxiety disorders and anxiety related behaviours are becoming more common within modern society. These anxious behaviours can be motivated by either internal or external factors. Theory and recent research suggests anxiety related behaviours are motivated by multiple components. These include biological, cognitive and social learning. This chapter used OCD to highlight the motivating factors driving anxious behaviour. Cognitive beliefs involving control, self efficacy and competence have a major role in guiding the compulsive actions. While the compulsive actions might provide temporary relief, they only strengthen the neural pathways worsening the condition. The content variation for the obsessions is suggested to be the result of anxiety passed down through evolution, and malfunctioning brain structures. While the frequency of the intrusive thoughts rely largely on how often an OCD sufferer engages in trying to suppress them. The constant attempt to suppress the thoughts worsens the condition creating further anxiety. Self Determination Theory has shown that psychological needs such as autonomy, competence and relatedness are vital for well being and personal growth. When these needs or instinctual goals are not met, the individual may engage in avoidance type behaviours.

See also

- Anxiety (Wikiversity)

- Self (Wikiversity)

- Positive Thinking (Wikiversity)

- Spiritual (Wikiversity)

References

Barrett, P.M., Farrell, L., Pina, A.A., Peris, T. & Piacentini, J. (2008). Evidence based psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent obsessive compulsive disorder. Journal of Clinical Child Adolescent Psychology, 37(1), 131-155.

Cisler, J.M., Olatunji, B.O., Lohr, J.M. & Williams, N.L. (2009). Attentional bias differences between fear and disgust for the role of disgust-related anxiety disorders. Cognition and Emotion, 23(4), 675-687.

Deci, E.L., & Ryan, R.M. (2008). Self determination theory : A macrotheory of human motivation, development and health. Canadian Psychology, 49(3), 182-185.

Hewitt, S.N., Egan, S., & Rees, C. (2009). Preliminary investigation of intolerance of uncertainty treatment for anxiety disorders. Clinical Psychologist, 13(2), 52-58.

Lee, T.H., Lim, S.K., Lee, K., Kim, H.T., & Choi, J.S. (2009). Conditioning induced attention bias for face stimuli measured with the emotional stroop task. Emotion, 9(1), 134-139.

Lang, P.J., & Mcteague, L.M. (2009). The anxiety disorder spectrum of fear imagery, physciological reactivity, and differential diagnosis. Anxiety Stress & Coping, 22(1), 5-25.

Lang, S., Kroll, A., Lipinksi, S.J., Wessa, M., Ridder, S., & Flor. (2009). Context conditioning and extinction in humans. European Journal of Neuroscience, 29(1), 823-832.

Lonsdorf, T., Weike, A.E., Nikama, P., Schalling, M., Alfons, H.O., & Ohman, A. (2009). Genetic gating of human fear learning and extinction. Psychological Science, 20(2), 198-206.

Reuven-Margil, 0., Dar, R., & Liberman, N. (2008). Illusion of control and behavioural control attempts in obsessive compulsive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117(2), 334-341.

Robinson, D., Wu, H., Munne, R., Ashtari, M., Alvir, J.M., Lerner, G., Koreen, A., Cole, K., & Bogerts, B. (1995). Reduced caudate nucleus volume in obsessive compulsive disorder, General Psychiatry, 52(5), 393-398.

Moulding, R., Kyrios, M., Doron, G., & Nedeljkovic, M. (2009). Mediated and direct effects of general control beliefs on obsessive compulsive symptoms. Journal of Behavioural Science, 41(2), 84-92.

Oconnor, J. (2007). The dynamics of protection and exposure in the development of obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 24 (3), 464-474.

Saxena, S., Gorbis, E., Oneill, J., Baker, S.K., Mandelkern, M.A., Maidment, K.M., Chang, S., London, E.D. (2009). Rapid effects of brief intensive cognitive-behavioural therapy on brain glucose metabolism in obsessive compulsive disorder. Molecular Psychiatry, 14, 197-205.

Starcevic, V., & Berle, D. (2006). Cognitive specificity of anxiety disorder a review of selected key contructs. Depression and Anxiety, 23, 51-61.

Zvolenski, M.J., Forsyth, J.P. (2007). A concurrent test of the anxiety sensitivity taxon. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 21(1), 72-90.