| Type classification: this is a lesson resource. |

| Subject Classification: this is a neuroscience resource. |

Goals

- To learn how conscious and unconscious emotions are generated in the brain

- To understand how mood and emotion affects cognition and how closely the two are linked

- To learn the basic principles of reward circuits and their role in emotional states

Neurological perspective of emotion

Emotion is so ubiquitous and essential for how one sees the world that becomes necessary to view emotion in a new way in order to interpret it scientifically. As such every emotional response, from love to hate, fear to joy, and everything in between, can be summed up (although not perfectly) as purely physiological responses to environmental events that serve to motivate away from harm and toward reward. While this is a rather bold assertion, it enables one to look at emotional responses objectively and on a purely neurological level.

In the brain, emotion can often be thought of as a more base impulse coming from the inner-middle regions of the brain, which is in conflict with the reasoned and advanced computation of the higher cortex. Although this model is not entirely wrong, it is important to acknowledge just how closely supposedly 'rational' cognitive processes are tinged by emotional experience. Thoughts and understanding even on a cortical level are often rooted in emotional experiences, in the sense that, for instance, while debating the place of law and morality in civilization may seem like a purely detached and cortical function, if one has never experienced emotional responses like pain or frustration judgments as to what constitutes right and wrong become impossible to make. Thus the story of emotion in the brain is a cross between the lower 'feeling' aspect, and the upper 'conscious' aspect.

Finally, much of emotion is below the threshold of consciousness. Only when activity spills over into the cerebrum is there a concrete and obvious awareness of one's own emotional state. Often, such moods are highly transient and even may be triggered by cues that one is not consciously aware of. In all cases however, emotion's main goal is to provide a means of understanding what is happening. So positive emotions cause a specific situation to be tied to feelings of reward, altering future decision making related to that situation or at least giving an understanding that that situation was a 'good' one, and vice versa for negative experiences.

Anatomy of emotion

When discussing emotion, the most important brain feature to mention is the limbic system. This large assemblage of closely interconnected and related brain regions toward the center of the brain is key for almost all aspects of emotional experience- from taking in raw sensory input through the thalamus to relaying up toward the frontal cortex. Each of the primary limbic system areas and their chief contribution to emotion is listed below:

- Thalamus: Central hub for taking in and beginning to process sensory data. Certain parts of the thalamus already tag certain environmental information as being emotionally salient- such as a rapidly approaching object signaling fear or a pleasant smell signaling comfort. These "tagged" sensory cues are then sent to the appropriate regions to be interpreted and compiled together into the whole situation

- Hippocampus: As might be expected, the hippocampus can connect experiences with memories, along with the either positive or negative feeling that comes along with those memories. When the hippocampus is "deciding" what information to store as memories, it relies heavily on what emotional reaction that information is provoking.

- Amygdala: As one of the most important regions for emotion, the amygdala does a wide array of crucial functions, from ascribing levels of emotional significance to inducing fear and anger and much more which is just now being discovered.

- Hypothalamus: Due to its relationship with the endocrine system, the hypothalamus is very important in getting the proper hormonal response that accompanies emotional states, especially those of fear and anxiety.

- Anterior cingulate cortex: Although a specific function is difficult to pinpoint, the anterior cingulate is highly activated by emotional situations and plays many complex roles in processes like personality.

Circuits and feelings

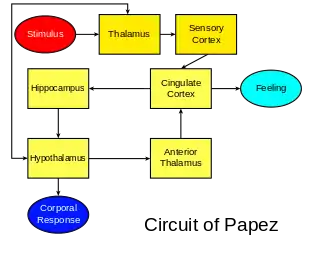

Because emotion is not just the product of one brain region but rather an emergent property of many working together, the best way to represent emotion on a neural level is through neural circuits. Paths may differ depending on the exact emotion (for example a fear response would be significantly different from a calm feeling) but a good general outline is depicted to the left. As emphasized earlier, emotion relies both on cortical processing and on processing done in the limbic system.

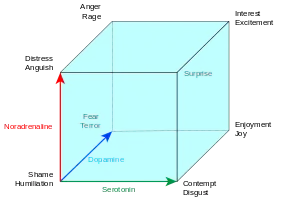

Much of emotion's practical value comes from its interplay with the reward circuit, which is a loosely defined collection of brain pathways that seem to produce pleasurable feelings when activated. It is hard to say whether a pleasurable emotion is something which activates the reward pathway, or if activation of the pathway itself creates the emotion which feels pleasurable, but in either case the positive feelings foster a desire to have those feelings repeated. This may manifest itself in intense motivation to achieve gratification, up to the point seen in addiction.