| Type classification: this is a lesson resource. |

| Subject Classification: this is a neuroscience resource. |

Goals

- To learn about the causes and mechanisms of neurological conditions such as epilepsy and addiction

- To understand how these conditions can be managed or even treated, as well as current directions of research

Epilepsy

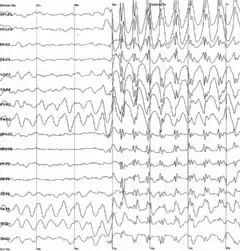

Epilepsy is complex set of disorders linked by the occurrence of neurological disturbances called seizures. A seizure is essentially any sudden and abnormal bout of electrical activity in the brain which can temporarily and severely interfere with brain functioning. Because epilepsy is such a diverse disorder, it can be grouped based on the general characteristics of any given patient's specific seizure pattern. These patterns- and their effects- are largely determined by where in the brain they seizures originate and how far they extend. A seizure is partial if it is restricted to a fairly localized area, and general if it is diffuse enough to disrupt the activity of almost all brain regions. Partial seizures are commonly linked to muscle twitching, hallucinations, and memory loss, but occur while the patient is still conscious. In contrast, general seizures imply a lack of consciousness and can cause paralysis or convulsing.

During routine operation, the brain is under a constant baseline level of neural activity that is carefully maintained by feedback mechanisms. For a seizure to occur, these mechanisms must be compromised, leading to uncontrolled activity. The way the brain usually preserves this balance is through careful inhibition by the neurotransmitter GABA. Many epileptic patients show low levels of GABA, and it is theorized that without GABA's crucial inhibitory effect, there is little to stop sudden jolts of electrical activity from going out of control and becoming a full seizure. Often, individuals with epilepsy find that they have specific triggers that cause seizures, or at least situations which serve as strong risk factors for a seizure happening.

Anticonvulsent drugs are one common treatment for epilepsy. These are especially effective against general seizures, but often only help reduce the frequency or severity of partial seizures. For much more extreme cases, it may be advised that a patient undergo surgery to remove the offending brain region acting as the seizure origin. Electrical stimulation can also reduce seizure rates, and is an alternative to surgery for severe cases.

Addiction

Addiction is simply defined as a dependency on something which is so strong that it becomes difficult or nearly impossible to go without it for any sustained period of time. The broad nature of this definition suggests that virtually anything can become the focus of an addition, so long as the craving for that thing is so strong as to create compulsive or uncontrollable behavior, especially toward the pursuit of acquiring more of the substance. While this definition is more psychologically-founded, the hallmarks of addiction can also be judged in terms of physical symptoms such as the side effects of substance withdrawal or damage to certain organs. These two aspects are highly specific to the addictive substance or activity in question, however, although the overarching idea is that an addiction compels one to proceed using a substance in spite of the negative consequences of doing so.

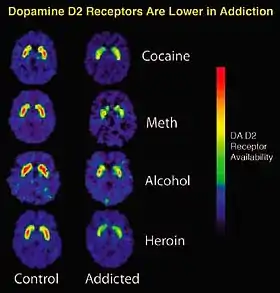

In terms of the neurobiology of addiction, a key factor is that the substance or behavior causes, at least initially, activation of a category of brain structures known as reward circuits. Activation of these circuits causes feelings of pleasure, which serves to motivate and drive the compulsive behavior. Many drugs achieve their effects by artificially activating parts of this system, such as by mimicking the effects of the neurotransmitter dopamine, which is one of the main chemicals involved in reward pathways, or by heightening sensitivity of reward-system receptors, or triggering the secretion of other pleasure-inducing neurotransmitters, or even by blocking certain brain regions including those involved in pain processing. The result of all of these effects is to create a craving for the substance so intense that it becomes almost impossible for a person to resist using normal cognitive routes of impulse control or long-term planning.

.svg.png.webp)

One inevitable consequence of chronic drug consumption- or even fairly short-term consumption in the case of the most powerful classes of drugs- is that the brain eventually develops a tolerance to the substance. This means that each indulgence of the addicted behavior has diminishing returns of reward sensations, so that higher amounts are needed just to achieve less of an effect than it once had. The compulsion is so great however that this rarely stops an addictive behavior, but on the contrary amplifies it by placing greater and greater emphasis on the ultimately futile pursuit of achieving the peaks of the first few uses. As more substance is ingested as a result of tolerance, the damaging effects to the body that accompanies it will also amplify, creating a cycle of ever-greater physical and psychological damage.

A variety of treatment options are available for those looking to escape this cycle of substance abuse. First, programs are available to gradually or quickly separate an individual from the addictive substance by placing them under controlled residential environments. As part of rehabilitation, certain medications can also be used to deter relapse, or a return to the addictive behavior. These include substances that reduce the often painful effects of withdrawal, others that prevent addictive drugs from having any pleasurable effect, and more general ones which reduce compulsivity. Alternatives are also available that use approaches such as behavioral counseling.