| Type classification: this is an essay resource. |

- This essay is on Wikiversity to encourage a wide discussion of the issues it raises moderated by the Wikimedia rules that invite contributors to “be bold but not reckless,” contributing revisions written from a neutral point of view, citing credible sources -- and raising other questions and concerns on the associated '“Discuss”' page.

- Everyone prefers information and sources consistent with their preconceptions.

This is a well-known phenomenon called “confirmation bias”. It feeds conflict, because each side believes they know things the others don't, which is usually true. This is amplified, because each side often avoids information and sources preferred by the other parties when the “others'” information and sources tend to conflict with “our” preconceptions.[1] When the parties to conflict speak different languages, it becomes difficult for individuals in each side to access the information consumed by the others, even if they want to.

- The mainstream media exploit this to profit those who control media funding and governance.

Whether accidentally or intentionally, different media organizations have segmented the media market in many different ways. The most obvious type of market segmentation is by language: Native speakers of Chinese or Arabic or French will likely consume different media than native English speakers. However, the media market is segmented in other ways as well. In the US, Fox News caters especially to so-called conservatives, and Fox and the more "liberal" media tend to demonize one another. Market segmentation has become Balkanization, with social media, especially Facebook, being particularly effective at Balkanizing the body politic in ways that support extremist groups, and terrorist attacks.[2]

The combination of these two phenomena imply the following:

- We are all trapped in our own echo chambers.[3]

At its worst, this implies the following for many and perhaps all armed conflicts:

- Collateral damage that "they" commit proves to us that they are at best criminally misled and maybe subhuman and must be resisted by any means necessary.

- Meanwhile, collateral damage that we commit is unfortunate but necessary from our perspective -- but proves to them that we are at best criminally misled and perhaps subhuman and must be resisted by any means necessary.

Threats

It becomes virtually (and sometimes even literally) treasonous to suggest that the other side may actually have valid concerns that are unreported or distorted in the media “we” consume. This phenomenon contributes to the maintenance of large nuclear arsenals, which seem to threaten the future of civilization.

These problems have many other serious but less lethal consequences:

- Research has documented how as the quality of local news declines, fewer people run for political office, fewer people vote, less money is spent on political campaigns, politicians don't work as hard for their constituents, and the cost of government goes up.

- Between 1925, the earliest data available, and 1975, roughly 0.1 percent of the US population was in state and federal prisons. In the last quarter of the twentieth century, it increased by a factor of five and has been roughly stable at half a percent of the population since. That change was not driven by a substantive increase in crime but rather by changes in the editorial policies of the mainstream commercial broadcasters to fire nearly all the investigative journalist and replace them with the police blotter. The public thought that crime was out of control and voted in a generation of politicians promising to get though on crime.[4]

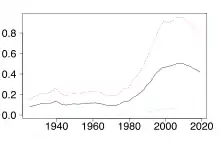

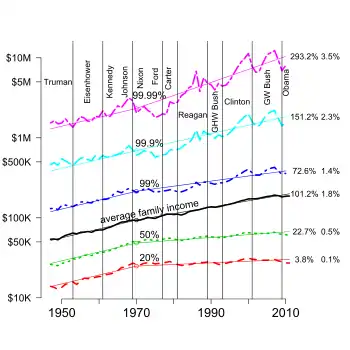

- The relatively recent explosion in income inequality in the US began around the same time as the mainstream commercial broadcasters were firing nearly all the investigative journalists and replacing them with the police blotter.

- The elimination of the Fairness Doctrine in the Fairness Doctrine in the US in 1987 seems to have contributed to an increase in political polarization in the US. This seems further to have been amplified since 2004 by the rise of for-profit social media like Facebook, YouTube and Twitter. Vaidhyanathan (2018) Antisocial Media[5] claims that companies like Facebook are "undermining democracy everywhere", because they make it profitable to target groups as small as twenty with ephemeral ads that currently disappear after a short while and therefore cannot be documented unless someone happens to capture it when they see it. "Facebook is working directly with campaigns — many of which support authoritarian and nationalist candidates".[6] Harvard social psychology professor emeritus Shoshana Zuboff says the algorithms used by internet companies like Facebook and Google produce "epistemic chaos", not merely "fake news" nor disinformation, because the intent is not to deceive but to attract profitable clicks, with no consideration of veracity.[7] Similarly, McMaster (2020) Battlegrounds[8] describes how the algorithms used by companies like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter "determine the presentation of content [in ways that] encourage further polarization and extreme views. ... Those who interact on network platforms self-segregate into homogenous groups that share beliefs on contentious issues such as gun control, climate change, and immigration. Liberals interact with liberals and conservatives interact with conservatives. The most divisive and emotional topics amplify different rather than common views. The internet and social media thus provided the [the Russian military] with a low-cost, easy way to divide and weaken America [and other countries, especially U.S. Western allies] from within", substantively degrading our national security according to McMaster.[9][10]

- However, this "undermining of democracy" attributed to "antisocial media" may also be attributed in part, at least in the US, to a concurrent decline in the money available for newspapers: The US has lost half its newspaper reporters in the last 10 years[11] and a quarter of its newspapers in the 15 last years.[12] Many of the newspapers that remain contain less substance while a substantial number publish less often.[13]

- In 1999 an America West flight made an emergency landing when two Saudis tried to break into the cockpit. That information was declassified in 2016 but has not entered the public discourse of US support for the Saudi war in Yemen, in spite of the evidence that honest law enforcement efforts have been overwhelmingly more effective in suppressing terrorism than use of military force. Between 150 thousnd and a million Iraqis who had nothing to do with the September 11 attacks died as a result of US-led military operations there between 2003 and 2007 -- between 50 and 300 times as many as those who died in the September 11 attacks. The two primary recruiters for Islamic terrorism seem to be Saudi Arabia and the US.

- Former US President Dwight Eisenhower, who left office in 1961, wrote in his 1963 autobiography, "I never talked or corresponded with anyone knowledgeable in Indochinese affairs who did not agree that had elections been held as of the time of the fighting [leading to the defeat of the French in 1954], possibly 80 per cent of the population would have voted for the Communist Ho Chi Minh".[14] This was the universal expert consensus that was not even mentionable in the mainstream media of that day in the US. Instead, substantial nationwide coverage was provided for unfounded claims by Senator Joseph McCarthy in 1952 as he accused the Democrats of "20 years of treason" for their relations with the USSR during the previous 20 years. The media support for McCarthy continued as he complained about "21 years of treason", as he complained that President Eisenhower was not doing enough to combat Communism. In this environment, US Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon all knew that the mainstream media in the US would effectively destroy their presidencies if the allowed the Vietnamese to govern themselves. Two US senators voted against the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in August 1964; both were defeated for reelection that year.

- As of 2020-12-26 the US is still at war in Afghanistan, even though more recent information indicates that the most effective responses to terrorism are negotiations and law enforcement, with military force being the least effective. Between 1968 and 2006 more terrorist groups won than were defeated militarily. Apparently, the primary result of "colateral damage" is to drive people off the sidelines to support one's opposition. This is consistent with the evidence that US government officials knew as early as 1999 that the Saudis and apparently no other government were providing substantive support for the preparations for the September 11 attacks, and the two primary recruiters for Islamic terrorism since have been Saudi Arabia and the US. However, US international business interests have long had better relations with Saudi Arabia than with Afghanistan and Iraq. This continues to give the mainstream media in the US a conflict of interest in honestly discussing these issues.

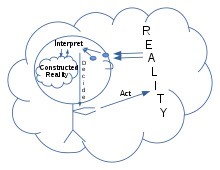

The social construction of conflict

In 1886 or 1887, Friedrich Nietzsche wrote that, “Facts do not exist, only interpretations.” In his 1922 book Public Opinion, Walter Lippmann said, "The real environment is altogether too big, too complex, and too fleeting for direct acquaintance" between people and their environment. Each person constructs a pseudo-environment that is a subjective, biased, and necessarily abridged mental image of the world, and to a degree, everyone's pseudo-environment is a fiction. People "live [and act] in the same world, but they think and feel [and decide] in different ones."[15] Lippman's “environment” might be called “reality,” and his “pseudo-environment” seems equivalent to what today is called “constructed reality.”

This becomes a problem, because

- The mainstream media create the stage upon which politicians read their lines.

For example, former President Eisenhower said, "I have never [communicated] with a person knowledgeable in Indochinese affairs who did not agree that had elections been held as of the time of the fighting [leading to the defeat of the French in 1954], possibly 80 per cent of the population would have voted for the Communist Ho Chi Minh".[16]

This universal expert consensus was completely absent from the mainstream political discourse in the US at that time. Consequently, the socially socially constructed image of Southeast Asia shared by the majority of the US body politic was very different from the lived experiences of most of people in that region. This gap seriously constrained the foreign policies of US Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon.

Similarly, there is a substantial body of evidence that suggests that (a) the two primary recruiters for Islamic terrorism may be Saudi Arabia and the US and (b) much of what the US has done in the name of the "War on Terror" has been counterproductive. This further suggests that substantive changes to US policy in this region could force major changes on US international business relations with the Saudis and possibly other authoritarian governments. Any media organization whose coverage was seen as potentially contributing to such changes might expect to lose advertising revenue from multinational business interests that might fear a loss of business from any such changes in policy.

This is illustrated by the line, "We have met the enemy and he is us", which was a common refrain of political cartoon character Pogo. Cartoonist Walt Kelly used this line several times from the McCarthy era of the 1950s, including with multiple issues during the Nixon administration (1969-1974) until Kelly died in 1973. See: 1971 Earth Day poster featuring political cartoon character Pogo saying, "We have met the enemy and he is us."[17]

Individual countermeasures

As individuals, we can reset our preconceptions to believe that our opposition will likely have sensible reasons for their positions, which are almost certainly unreported or misrepresented in the media we consume.

- Get curious, not angry.

This pushes us to stop paying as much attention to the mainstream media most readily available to “us” and look for alternative sources of information.

It also pushes us to be more accepting of potentially conflicting information. Even if what we hear from other sources seems to be wrong, we might be wise to accept that others may believe those other sources, especially if such beliefs might explain the behaviors we perceive.

- If we understand "their" perceptions better, it could reduce the chances that we would unwittingly offend them and increase the chances that we can resolve the conflict constructively. Their behaviors are driven by what they think, not what we think.

Because of confirmation bias, leaders and media outlets become trapped by their own rhetoric: We cannot expect leaders to say something they believe might reduce their following. We cannot expect a media outlet to publish anything that might reduce their audience or offend key managers or the people who control their funding.

- Watchdogs rarely bark at those who feed them.[18]

Manage our attention

Discussions of time management have discussed the "attention economy". Michael Goldhaber encourages us to think carefully about how we manage our attention so we used it in more focused, intentional ways, especially in how we use modern information technology.[19]

Noncommercial social media

Individuals could experiment with noncommercial social media like Diaspora or Mastodon: Noncommercial social media may not be as highly tuned to subtle human motivations as for-profit products like Facebook, but they also seem much less likely to increase conflict. One person who finds something useful may be able to convince friends to follow to the alternative noncommercial platform.[20]

Chenoweth's 3.5 percent rule

Fortunately, change is possible, as documented in research by Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan. They created a database of all the major violent and nonviolent governmental change efforts of the twentieth century -- over 300 of them. Twenty-five percent of the violent campaigns were successful and 53 percent of the nonviolent campaigns succeeded. So nonviolence was twice as likely to succeed as violence.[21]

Moreover, every campaign that achieved the support of 3.5 percent of the population was successful. And all of those were nonviolent.[22] If 3.5 percent of the population anyplace finds credible sources of information that contradict the local mainstream media and start asking their friends and neighbors their reactions to these contrary perspectives, they can force a change in public policy. Autocrats of the right and the left have been forced from power by nonviolent movements.

A major contributor to ending the US war in Vietnam was the gradual increase in opposition to the war in the US. By 1970 only a third of Americans believed that the US had not made a mistake by sending troops to fight in Vietnam.[23][24]

In a crudely similar way, the first Earth Day celebrations in 1970 reportedly "brought 20 million Americans out into the spring sunshine for peaceful demonstrations in favor of environmental reform."[25] That was almost 10 percent of the US population of 203 million. The United States Environmental Protection Agency began functioning later that year, December 2.

In Chenoweth and Stephan's successful nonviolent revolutions, in the anti-Vietnam War movement, and in the creation of the EPA, the movement for change started small and built until the mainstream media could no longer conceal enough of the evidence to prevent the changes that people were demanding. The media was forced to change or lose audience, and the leaders were forced to follow. In each case, dissidents stopped believing the dominant narrative and convinced enough others to join them that the media and the leaders were forced to change.

These change movements might have proceeded faster if the people involved had been better at (a) finding credible sources that contradicted the mainstream narrative and (b) asking others in nonthreatening ways what they thought about those contrary sources.

Wikipedia

A source that generally has fewer problems with these issues is Wikipedia. It has been recognized as a place where on controversial topics "the two sides actually engaged each other and negotiated a version of the article that both can more or less live with. This is a rare sight indeed in today’s polarized political atmosphere, where most online forums are echo chambers for one side or the other”.[3]

Wikipedia works, because almost anyone can change almost anything on Wikipedia. What stays tends to be written from a neutral point of view citing credible sources. Changes that do not conform to this standard are routinely reverted or modified by others to be more neutral and / or to cite credible sources.

This is a major threat to people in power. Various countries, most notably China, have blocked all or parts of Wikipedia. Turkey blocked all language editions of Wikipedia between 2017-04-29 and 2020-01-15; Wikipedia became available again in Turkey after the Turkish Constitutional Court ruled that the block was unconstitutional.[26]

In March 2013 the French interior intelligence agency DCRI contacted the Wikimedia Foundation claiming that an article in the French-language Wikipedia about a French military compound contained classified information and demanded that it be deleted immediately. The Wikimedia Foundation said it "receives hundreds of deletion requests every year and always complies with clearly motivated requests." In this case, however, the Wikimedia Foundation considered that they did not have enough information and refused the DCRI request. On April 4, 2013, the DCRI summoned a volunteer administrator of the French Wikipedia and resident of France and demanded he immediately delete the article. The volunteer complied, believing he would otherwise be immediately incarcerated and prosecuted.[27] The article was later restored by another Wikipedia contributor who lived outside France.

Attempts to censor Wikipedia have also come from Australia, Germany, Iran, Pakistan, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, the United Kingdom, Uzbekistan, and Venezuela.[28]

Conservatives in the US have been so concerned about what they claim is a “liberal” bias in Wikipedia that they created “Conservapedia” as an alternative.

Risks in making unpopular statements

Opposing the dominant narrative always involves risk. Benjamin Franklin's grandson, Benjamin Franklin Bache, was arrested and charged with libel in 1798 for publishing unflattering remarks about President John Adams.[29] During the twentieth century, Jehova's Witnesses were imprisoned and repeatedly attacked by violent mobs.[30] During the Civil rights movement in the United States, civil rights activists were violent attacked and imprisoned, with some being killed, often with the complicity of law enforcement.[31]

With an issue like the environment that does not involve national security in a fairly open society like the US, the risks from offending the people you talk with are usually fairly low. Morever, the risks from nonviolence are nearly always less than those from violence. Nonviolence is also more likely to attract supporters and less likely to increase the support for your opposition.

A key question is how can one become more persuasive? The operating hypothesis here is that one can often be more persuasive by (a) understanding better the people with whom one is communicating and (b) presenting sources and (c) requesting feedback in a nonthreatening manner.[21]

Countermeasures that can be taken by organizations

Governments could reduce the problems created by confirmation bias by funding citizen-directed subsidies for (a) journalism and (b) improved research to improve the use of evidence in public policy. Commercial organizations could similarly offer to donate a small percentage of their gross to such purposes selected by their customers.

- I do not want either government bureaucrats nor corporate bureaucrats censoring the information I consume.

The US Postal Service Act of 1792 provided citizen-directed subsidies for journalism, funds whose disbursement was controlled by newspaper subscribers, not by government officials nor advertisers. Under this act, newspapers were delivered up to 100 miles for a penny when first class postage was between 6 and 25 cents depending on distance. McChesney and Nichols (2016) said this represented roughly 0.2 percent of US Gross Domestic product (GDP) in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.[32] "In 1794 newspapers made up 70 percent of post office traffic; by 1832 the figure had risen to well over 90 percent."[33] They said it had a huge impact of the subsequent success of the US, because it encouraged literacy and limited political corruption, both of which are known to contribute to economic growth. The comparison with contemporary New Spain, which became Mexico in 1821, is striking: The US prospered and grew while New Spain / Mexico fractured, shrank and stagnated economically.[34]

Relevant research

To counter the growing threat to democracy from the decline of news media, McChesney and Nichols recommend an internet-savvy reincarnation of the US Postal Service Act of 1972, again funded at 0.2 percent of GDP. This could be done in multiple ways that would be controlled by the public, not politicians nor big money interests. McChesney and Nichols suggested giving each citizen a voucher worth $100 per year (for 0.2 percent of GDP) that they could spend on any combination of qualified noncommercial investigative journalist organizations.[32] Karr and Aaron (2019) recommend a tax on "targeted advertising" sold by companies like Facebook "to fund a public-interest media system that places civic engagement and truth-seeking over alienation and propaganda.[35]

Yale Law professor Bruce Ackerman suggested disbursing a comparable amount on the basis of qualified mouse clicks.[36] Dan Hind proposed "public commissioning" of news, where "Journalists, academics and citizen researchers would post proposals for funding" investigative journalism on a particular issue with a public trust funded from taxes or license fees, with the public voting for the proposals they most supported.[37] Dean Baker suggested an "Artistic Freedom Voucher" to provide citizen-directed subsidies to journalists, writers, artists and musicians, who place their work in the public domain. He claims that our current copyright system locks entirely too much information behind paywalls for far longer than required “to promote the progress of science and useful arts," as required by the United States Constitution.[38][39] This is particularly true for refereed academic journals, the vast majority of which offer zero financial remuneration for published articles: With rare exceptions, the authors sole compensation comes from the recognition of their expertise that the publication provides, supplemented in some cases by academic promotions. For all such journals, copyright restrictions are obstacles to "the progress of science and useful arts," in blatant violation of the United States Constitution.[40]

Julia Cagé recommended “Nonprofit Media Organizations (NMOs),” being charitable foundations with governance shared between the audience, employees and funders..[41] In July 2020 she founded "Un bout du monde" ("One end of the world"), which advocates citizen ownership of the media, insisting, "Information is a public good. The time has come to act and reconquer our media!"[42]

Models similar to Cagé's NMO are provided by community radio stations operated and managed by volunteers. One example is KKFI, a community radio station whose bylaws say it is owned by its “active volunteers”, who must donate at least 3 hours per month on average for over 6 months. Almost 90 percent of their 24/7 broadcast hours are locally produced by volunteers. The rest come from sources like the Pacifica radio network, that includes over 200 listener-sponsored radio stations.[43]

In 2018 the government of New Jersey created a "Civic Information Consortium", which "is a public charity and a collaboration among five of the state’s leading public higher-education institutions: The College of New Jersey, Montclair State University, the New Jersey Institute of Technology, Rowan University and Rutgers University." This is a nonprofit that provides grants to support quality local journalism. Applicants must provide real benefit to the community in collaboration with university partners.[44]

Advertising and accounting

However, 0.2 percent of GDP may not be enough: By the middle of the nineteenth century, advertising was becoming the primary source of funding for journalism. Between 1919 and 2007, advertising averaged roughly 2 percent of GDP in the US.

This threatens the editorial independence of mainstream media, because the full range of responsible expert opinion on any major issue is rarely if ever adequately portrayed in the mainstream media. Examples will be discussed in companion articles.

However, the problem of malfeasance in government can actually be divided further into two components:

- 1. An insufficiency of research on the relative effectiveness of alternative approaches to societal problems, and

- 2. Public dissemination of and debate on the results of such research and on where more research is needed.

Both of these deficiencies are exacerbated by the suppression and distortion of information that might threaten the social status of those who control media funding and governance.

Citizen-directed subsidies for journalism should help overcome the second deficiency.

To overcome the first deficiency, this article suggests we consider citizen-directed subsidies for research with options proposed for "public commissioning," as suggested by Hind, mentioned above.[37]

As a model for an appropriate level of funding for citizen-directed subsidies for research, we might consider how much society spends on accounting and auditing. Most government agencies account for expenditures to the last penny, while the accounting for results rarely gets more than lip service.

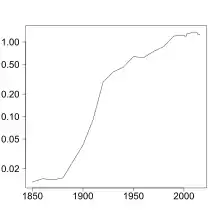

The Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) provides microdata samples from various US and international surveys. The accompanying plot of “Accountants and Auditors as a percent of US households” shows households including someone employed as an accountant or auditor increasing from 0.013 percent of households in 1850 to 1.3 percent in 2006 and since.

This suggests targets of 2 percent of GDP for citizen-directed subsidies for journalism and 1 percent for citizen-directed subsidies for research.

This may sound like a lot of money, but it's only roughly 18 months of the economic growth that the US has experienced on average since the end of World War II.[45]

An important aspect of this idea is that some businesses already donate a portion of their profits to charities selected by their customers.[46] We can ask them to help improve the functioning of democracy.

Similarly, governmental bodies could devote a small portion of their budgets for such citizen-directed subsidies. Citizens could ask local politicians to fund what might be called an endowment for journalism that would disburse funds to qualified nonprofit media organizations in proportion to, e.g., qualified internet clicks from IP addresses of residents of the jurisdiction of their respective governmental body. Commercial organizations could advertise their support for democracy by agreeing to donate, e.g., 0.1 or 1 percent of their gross or net to such an endowment for journalism, to be distributed in proportion to the desires of their customers as expressed each time they purchase or later via some mechanism, e.g., sending a photo of a receipt to such an endowment for journalism.

A reasonable target might be to match what the organizations already spend on advertising, public relations, and accounting.

Research needed

The details of how to do this effectively in the internet age still need further development. If some organizations publicly agreed to donate a portion of their budgets for this purpose, that could make it easier to get grant money for further research and conferences on exactly how to do this.

Tracking ads

Governments could also require all organizations that receive compensation for displaying content to an audience to a central repository like the Internet Archive with appropriate metadata to make it easy to search and identify the content, the audience, and the distributing organization. Exemptions could be made for organizations that receive less than, e.g., 10 times the median household income,[47] but it should include all funds received for displaying content, whether it's called advertising, underwriting, boosting, or something else.

The rise of social media has made it increasingly difficult for political candidates or minorities targeted by disinformation to even know what's driving the supporters of their opponents. Requiring paid content to be submitted to a central repository like this would make it much easier for defamed individuals to obtain evidence on the defamation and sue for libel or file criminal complaints for incitement to riot. This with existing law might be enough to reduce the problem of "fake news" to a more manageable level, especially in combination with an International Conflict Observatory, mentioned below.

Rather than giving government and corporate bureaucrats legal tools to censor the media and suppress dissent, we should give aggrieved parties tools they can use to find out if they've been defamed. These databases should allow defamed individuals or groups to document the exact nature and source of the disinformation. And they need the ability to seek redress of grievances in the courts.

Liability for defamation

Dean Baker insists that internet platforms that accept compensation for displaying content, whether it's called advertising, underwriting, boosting or something else, should be legally liable for the content in the same way as print media are. If they do not receive compensation, they should not be held liable for the content.[48]

Fairness doctrine

Between 1949 and 1987 the FCC fairness doctrine required broadcasters in the US to both present controversial issues of public importance and to do so in a manner that was—in the FCC's view—honest, equitable, and balanced. The repeal of the fairness doctrine in 1987 seems to have contributed to the increase in partisanship that has occurred since then. This suggests that if we want domestic tranquility, the fairness doctrine should be reinstated and made applicable to all media that carry advertising or underwriting. And the courts should be empowered to decide what is honest, equitable, and balanced.

Conservatives claim that a fairness doctrine would target conservative media.[49] A new fairness doctrine should target unfair media, whether liberal, conservative, or of any other ideology.

Related work

Corruption trilogy

The so-called "Corruption trilogy"[50] consists of the following:

- . Everyone makes most decisions based on what comes most readily to mind.[51]

- . We prefer information and sources that reinforce our preconceptions -- confirmation bias.

- . The mainstream media everywhere exploit these defects in how humans make decisions to benefit those who control media funding and governance.

The first two points of this “Corruption trilogy” (or “Misinformation trilogy”, to use a more neutral term) is well documented in Thinking, Fast and Slow, which summarizes important work for which Daniel Kahneman won the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics, even though he's not an economist: Kahneman established that the models of a “rational person” that have been used for decades by economists do not adequately describe how people think and make decisions.[52]

“Confirmation bias and conflict” is manifested in the research by Waytz, Young, and Ginges (2014) that documented “motive attribution asymmetry” in how members of the Republican and Democratic political parties in the US view each other and how Israelis and Palestinians view each other: Everyone tends to attribute their own and their own group's involvement in conflict to ingroup love more than outgroup hate but attribute the opposing party’s involvement to outgroup hate more than ingroup love. Waitz et al's research included a hopeful experiment that involved offering financial incentives for accuracy in evaluating the opposing party: They found that the financial incentives can mitigate this bias and its consequences. They suggested “that recognizing this attributional bias and how to reduce it can contribute to reducing human conflict on a global scale.” In terms of this discussion of “confirmation bias and conflict”, the fact that something (like financial incentives) can contribute to reducing conflict further suggests that other interventions may also reduce conflict. This provides weak but perhaps nonnegligible support for the interventions suggested above.

Arthur C. Brooks, former President of the American Enterprise Institute, has lamented “Our Culture of Contempt” with “divisive politicians, screaming heads on television, hateful columnists, angry campus activists and seemingly everything on the contempt machines of social media.” It works by confirmation bias and motive attribution asymmetry. He says we would be happier as people and more successful in pursuing our own political objectives if we teach ourselves not to disagree less but to disagree better: He asks us to “turn away the rhetorical dope peddlers — the powerful people on your own side who are profiting from the culture of contempt. ... When you find yourself hating something, someone is making money or winning elections or getting more famous and powerful. Unless a leader is actually teaching you something you didn’t know or expanding your worldview and moral outlook, you are being used.” Brooks asks us to never to treat others with contempt. He says that doing so will make it easier for us to find common ground with our adversaries and create win-win deals that are not possible when we treat others with contempt -- and make us happier as individuals even if it doesn't change the nature of a conflict.[53]

In public testimony before the House Oversight Committee 2019-02-27, Michael Cohen, Donald Trump's attorney and business associate, 2006-2018, said, “I fear that if [Mr. Trump] loses the election in 2020, that there will never be a peaceful transition of power.”[54] Journalist David Neal said this was due to motive attribution asymmetry, and the future of democratic government in the US may depend on whether after the November 2020 elections, the US body politic can overcome the divisions Cohen mentioned.[55]

International Conflict Observatory

An "International Conflict Observatory" might help bridge the divide in conflicts by helping each side better understand its opposition. This might reduce the risk of counterproductive actions by xenophobes and contribute to the development of "win-win" resolutions of conflict.

This claim is consistent with the discussion above, noting that Wikipedia has been recognized as a place where on controversial topics "the two sides actually engaged each other", and built bridges outside their echo chambers.[3]

Bibliography

- Daniel Kahneman (25 October 2011), Thinking, Fast and Slow, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, OCLC 706020998, Wikidata Q983718.

- Robert W. McChesney; John Nichols (2016), People get ready: The fight against a jobless economy and a citizenless democracy, Nation Books, Wikidata Q87619174.

- Siva Vaidhyanathan (12 June 2018), Antisocial Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-084118-8, Wikidata Q56027099.

- Adam Waytz; Liane L Young; Jeremy Ginges (20 October 2014), "Motive attribution asymmetry for love vs. hate drives intractable conflict.", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111 (44): 15687–15692, doi:10.1073/PNAS.1414146111, ISSN 0027-8424, PMC 4226129, PMID 25331879, Wikidata Q34480942.

References

- ↑ Confirmation bias seems to provide a deep psychological foundation for “motive attribution asymmetry” documented in the research of Waytz, Young, and Ginges (2014).

- 1 2 3 Peter Binkley (2006), "Wikipedia Grows Up", Feliciter (2): 59–61, Wikidata Q66411582

- ↑ Gary W. Potter; Victor W. Kappeler, eds. (1996), Constructing Crime: Perspectives on Making News and Social Problems, Waveland Press, Wikidata Q96343487. Vincent F. Sacco (2005), When Crime Waves, SAGE Publishing, Wikidata Q96344789.

- ↑ Siva Vaidhyanathan (12 June 2018), Antisocial Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-084118-8, Wikidata Q56027099

- ↑ pp 195-196 of 275 and chapter 6. "The Politics Machine" and its section on "The Damage" more generally.

- ↑ Shoshana Zuboff (29 January 2021), "The Coup We Are Not Talking About", The New York Times, ISSN 0362-4331, Wikidata Q105287368.

- ↑ H. R. McMaster (2020), Battlegrounds: The Fight to Defend the Free World, HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0-06-289948-4, Wikidata Q104774898, esp. p. 47.

- ↑ See also McMaster (2020, p. 63).

- ↑ Concerns with "antisocial media" have also been expressed by Cornell economics professor emeritus Robert H. Frank. He acknowledged, "Rising concern about social media abuses", especially "their contribution to the spread of misinformation, hate speech and conspiracy theories." He noted that, "Because the economic incentives of companies in digital markets differ so sharply from those of other businesses, traditional antitrust measures won’t curb those abuses. ... [D]igital aggregators like Facebook ... make money not by charging for access to content but by displaying it with finely targeted ads based on the specific types of things people have already chosen to view. If the conscious intent were to undermine social and political stability, this business model could hardly be a more effective weapon." He suggests a subscription model. However, if the internet companies also make money from advertising, it's not clear if that would do more than just exclude the poor from social media. He concluded, "Proposals for regulating social media merit rigorous public scrutiny. But what recent events have demonstrated is that policymakers’ traditional hands-off posture is no longer defensible." Robert H. Frank (11 February 2021), "The economic case for regulating social media", The New York Times, ISSN 0362-4331, Wikidata Q105583420. For an alternative response, see Dean Baker's proposal to make companies like Facebook liable for defamation in content they differentially promote in the same way that the New York Times is liable for defamation not only in content they originate but in ads they carry. See Dean Baker (18 December 2020), Getting Serious About Repealing Section 230, Center for Economic and Policy Research, Wikidata Q105418677, discussed elsewhere in this article.

- ↑ 2010 - 2020

- ↑ 2005 - 2020

- ↑ Penny Abernathy (2020), News Deserts and Ghost Newspapers: Will local news survive?, University of North Carolina Press, Wikidata Q100251717. Similarly, Report for America notes that the number of newspaper reporters in the US fell 60 percent from 455,000 in 1990 to 183,200 in 2016. See "About Us" at the website for Report for America, Wikidata Q76373709, accessed 2021-01-08.

- ↑ Dwight D. Eisenhower (1963), Mandate for Change: The White House Years 1953-1956: A Personal Account, Doubleday, Wikidata Q61945939, p. 372.

- ↑ Walter Lippmann (1922), Public Opinion, Wikidata Q1768450, pp. 16, 20.

- ↑ Dwight D. Eisenhower (1963), Mandate for Change: The White House Years 1953-1956: A Personal Account, Doubleday, Wikidata Q61945939, chapter = 14. Chaos in Indochina, p. 372.

- ↑ This 1971 political cartoon is displayed in the Wikipedia article on Pogo but is not displayed here, the different use suggests that the "irreplaceable" argument used to justify a "fair use" claim there would not apply here with equal force.

- ↑ In "The Adventure of Silver Blaze", Arthur Conan Doyle had Scotland Yard detective Gregory ask, "Is there any other point to which you would wish to draw my attention?" Holmes replied, "To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time." Gregory responded, "The dog did nothing in the night-time." Holmes observed, "That was the curious incident." It is naive to expect a so-called watchdog press to bark at those who provide the money they need to survive. Media organizations that report too much generally lose funding and cease publishing or change their editorial policies. Investigative journalists who threaten to expose too much don't stay long with the mainstream media. Those who remain can have great careers, and are often incensed at the suggestion that they somehow pull their punches. Many of those seem unaware that journalists who ask "inappropriate" questions that might offend people who give them money rarely last long in those organizations.

- ↑ For an interview with Michael Goldhaber, see Charlie Warzel (4 February 2021), "I Talked to the Cassandra of the Internet Age", The New York Times, ISSN 0362-4331, Wikidata Q105397170.

- ↑ There has also been a discussion of meta:WikiSocial. However as of this writing it seems not to have produced anything tangible. See also Everyone's favorite news site.

- 1 2 Erica Chenoweth; Maria Stephan (2011), Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict, Columbia University Press, Wikidata Q88725216

- ↑ Erica Chenoweth (4 November 2013), My Talk at TEDxBoulder: Civil Resistance and the “3.5% Rule”, Wikidata Q62223350

- ↑ Lunch, W. & Sperlich, P. (1979). The Western Political Quarterly. 32(1). pp. 21–44

- ↑ Hagopain, Patrick (2009). The Vietnam War in American Memory. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 13–4. ISBN 978-1558496934., cited from the Wikipedia article on the w:Vietnam War#Opposition to U.S. involvement, 1964–73, accessed 2020-03-24.

- ↑ Jack Lewis (November 1985). "The Birth of EPA". w:United States Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on September 22, 2006.. Cited from the Wikipedia article on "Earth Day", 2020-03-24.

- ↑ Can Sezer; Daren Butler; Ali Kucukgocmen; Ezgi Erkoyun; Stephen Coates (14 January 2020), Turkey ban on Wikipedia lifted after court ruling, Reuters, Wikidata Q88728168

- ↑ Christophe Henner (6 April 2013), "French homeland intelligence threatens a volunteer sysop to delete a Wikipedia Article", Wikimedia France, Wikidata Q88563098

- ↑ Wikipedia article on "Censorship of Wikipedia", retrieved 2020-03-26.

- ↑ Raffi Andonian, "The Adamant Patriot: Benjamin Franklin Bache as Leader of the Opposition Press", University of Pennsylvania Libraries, Wikidata Q88571873

- ↑ Archibald Cox (1987), The court and the constitution, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Wikidata Q88575527, esp. p. 189

- ↑ Athan Theoharis; Tony G. Poveda; Susan Rosenfeld; Richard Gid Powers, eds. (1999), The FBI : a comprehensive reference guide, Oryx Press, Wikidata Q88578313>

- 1 2 Robert W. McChesney; John Nichols (2016), People get ready: The fight against a jobless economy and a citizenless democracy, Nation Books, Wikidata Q87619174, p. 167

- ↑ Robert W. McChesney (2004), The Problem of the Media: U.S. Communication Politics in the 21st Century, Monthly Review Press, ISBN 1-58367-105-6, Wikidata Q7758439, p. 33.

- ↑ Wikiversity, "The Great American Paradox", accessed 2020-03-26.

- ↑ Timothy Karr; Craig Aaron (February 2019), Beyond Fixing Facebook (PDF), Free Press, Wikidata Q104624308.

- ↑ Bruce Ackerman (2010), The decline and fall of the American republic, Harvard University Press, Wikidata Q87626180, ch. 5. Enlightening politics. See also Bruce Ackerman (June 2013), "Reviving Democratic Citizenship?", Politics & Society, 41 (2): 309–317, doi:10.1177/0032329213483103, ISSN 0032-3292, Wikidata Q29041557

- 1 2 Hind, Dan (2010). "10. Public Commissioning". The Return of the Public. Verso. pp. 159–160. ISBN 978-1-84467-594-4.

- ↑ Baker, Dean (November 5, 2003), The Artistic Freedom Voucher: An Internet Age Alternative to Copyrights (Briefing paper), Center for Economic and Policy Research, retrieved 2017-03-30.

- ↑ Dean Baker (2016), Rigged: How globalization and the rules to the modern economy were structured to make the rich richer, Center for Economic and Policy Research, Wikidata Q100216001.

- ↑ Lawrence Lessig was lead counsel for the plaintiff in Eldred v. Ashcroft, in which the Supreme Court of the United States decided that the US Congress was within its authority to extend copyright terms as it had with the 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act. However, refereed academic literature was not considered in that case. See also Free Culture: Lessig, Lawrence (2015). Free Culture: How Big Media Uses Technology and the Law to Lock Down Culture and Control Creativity (US paperback ed.). Petter Reinholdtsen. ISBN 978-82-690182-0-2.

- ↑ Julia Cagé (2016), Saving the Media: Capitalism, Crowdfunding, and Democracy, translated by Arthur Goldhammer, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-65975-9, OL 30399843M, Wikidata Q54640583

- ↑ Un bout du Monde, Wikidata Q105090926 and Arthur Porto (29 September 2020), "Un Bout du Monde: pour un actionnariat citoyen des médias!", Mediapart (in French), ISSN 2100-0735, Wikidata Q102700755. In January 2020 Cagé was elected President of the Society of readers of the famous Parisian daily, Le Monde, becoming their first female president. See Thierry Wojciak (20 January 2020), "Julia Cagé à la présidence de la Société des lecteurs du Monde", CB News (in French), Wikidata Q102642608 and "Communiqué : Julia Cagé devient présidente de la Société des lecteurs du « Monde »", Le Monde (in French), 20 January 2020, ISSN 0395-2037, Wikidata Q102653771.

- ↑ Bylaws and Policies, Wikidata Q88190284

- ↑ Mike Rispoli (30 September 2020), "Why the Civic Info Consortium Is Such a Huge Deal", Free Press, Wikidata Q104819595.

- ↑ MeasuringWorth, Wikidata Q88193829

- ↑ e.g., CREDO Mobile.

- ↑ The United States Census Bureau publishes various reports giving numbers like this, e.g., Income and Poverty in the United States: 2019, which reported that, "Median household income was $68,703 in 2019".

- ↑ Dean Baker (18 December 2020), Getting Serious About Repealing Section 230, Center for Economic and Policy Research, Wikidata Q105418677.

- ↑ e.g., "'Fairness' is Censorship". The Washington Times. June 17, 2008. Retrieved July 1, 2008.

- ↑ Spencer Graves (October 2019), "Corruption trilogy" (PDF), PeaceWorks Kansas City Newsletter, Wikidata Q89273749.

- ↑ This is the "fast thinking" described in Thinking, Fast and Slow by research psychologist Daniel Kahneman, who won the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize on Economic for his leadership in developing much of the research summarized in Thinking, Fast and Slow.

- ↑ Kahneman's seminal contributions helped create a branch of economics research called “behavioral economics”.

- ↑ Arthur C. Brooks (2 March 2019), "Our culture of contempt", The New York Times, ISSN 0362-4331, Wikidata Q92126239.

- ↑ Kevin Breuninger; Dan Mangan (27 February 2019), "Michael Cohen: 'I fear' Trump won't peacefully give up the White House if he loses the 2020 election", CNBC, Wikidata Q92133972.

- ↑ David Neal (3 March 2019), "Psychological group bias distorted by technology stokes dangerous primal tribalism", Working Journalist Press, Wikidata Q92132254