II

Number One"

IT was more than a week after the funeral of my poor friend Humphrey Challoner that I paid my first regular visit of inspection to his house. I had been the only intimate friend of this lonely, self-contained man and he had made me not only his sole executor but his principal legatee. With the exception of a sum of money to endow an Institute of Criminal Anthropology, he had made me the heir to his entire estate, including his museum. The latter bequest was unencumbered by any conditions. I could keep the collection intact, I could sell it as it stood or I could break it up and distribute the specimens as I chose; but I knew that Challoner's unexpressed wish was that it should be kept together, ultimately to form the nucleus of a collection attached to the Institute.

It was a gray autumn afternoon when I let myself in. A caretaker was in charge of the house, which was otherwise unoccupied, and the museum, which was in a separate wing, seemed strangely silent and remote. As the Yale latch of the massive door clicked behind me, I seemed to be, and in fact was, cut off from all the world. A mysterious, sepulchral stillness pervaded the place, and when I entered the long room I found myself unconsciously treading lightly so as not to disturb the silence; even as one might on entering some Egyptian tomb-chamber hidden in the heart of a pyramid.

I halted in the center of the long room and looked about me, and I don't mind confessing that I felt distinctly creepy. It was not the skeleton of the whale that hung overhead, with its ample but ungenial smile; it was not the bandy-legged skeleton of the rachitic camel, nor that of the aurochs, nor those of the apes and jackals and porcupines in the smaller glass case; nor the skulls that grinned from the case at the end of the room. It was the long row of human skeletons, each erect and watchful on its little pedestal, that occupied the great wall-case: a silent, motionless company of fleshless sentinels, standing in easy postures with unchanging, mirthless grins and seeming to wait for something. That was what disturbed me.

I am not an impressionable man; and, as a medical practitioner, it is needless to say that mere bones have no terrors for me. The skeleton from which I worked as a student was kept in my bedroom, and I minded it no more than I minded the plates in "Gray's Anatomy." I could have slept comfortably in the Hunterian Museum—other circumstances being favorable; and even the gigantic skeleton of Corporal O'Brian—which graces that collection—with that of his companion, the quaint little dwarf, thrown in, would not have disturbed my rest in the smallest degree. But this was different. I had the feeling, as I had had before, that there was something queer about this museum of Challoner's.

I walked slowly along the great wall-case, looking in at the specimens; and in the dull light, each seemed to look out at me as I passed with a questioning expression in his shadowy eye-sockets, as if he would ask, "Do you know who I was?" It made me quite uncomfortable.

There were twenty-five of them in all. Each stood on a small black pedestal on which was painted in white a number and a date; excepting one at the end, which had a scarlet pedestal and gold lettering. Number 1 bore the date 20th September, 1889, and Number 25 (the one with the red pedestal) was dated 13th May, 1909. I looked at this last one curiously; a massive figure with traces of great muscularity, a broad, Mongoloid head with large cheekbones and square eye-sockets. A formidable fellow he must have been; and even now, the broad, square face grinned out savagely from the case.

I turned away with something of a shudder. I had not come here to get "the creeps." I had come for Challoner's journal, or the "Museum Archives" as he called it. The volumes were in the secret cupboard at the end of the room and I had to take out the movable panel to get at them. This presented no difficulty. I found the rosettes that moved the catches and had the panel out in a twinkling. The cupboard was five feet high by four broad and had a well in the bottom covered by a lid, which I lifted and, to my amazement, found the cavity filled with revolvers, automatic pistols, life-preservers, knuckle-dusters and other weapons, each having a little label—bearing a number and a date—tied neatly on it. I shut the lid down rather hastily; there was something rather sinister in that collection of lethal appliances.

The volumes, seven in number, were on the top shelf, uniformly bound in Russia leather and labeled, respectively, "Photographs," "Finger-prints," "Catalogue," and four volumes of "Museum Archives." I was about to reach down the catalogue when my eye fell on the pile of shallow boxes on the next shelf. I knew what they contained and recalled uncomfortably the strange impression that their contents had made on me; and yet a sort of fascination led me to take down the top one—labelled "Series B 5"—and raise the lid. But if those dreadful dolls' heads had struck me as uncanny when poor Challoner showed them to me, they now seemed positively appalling. Small as they were—and they were not as large as a woman's fist—they looked so life-like—or rather, so death-like—that they suggested nothing so much as actual human heads seen through the wrong end of a telescope. There were five in this box, each in a separate compartment lined with black velvet and distinguished by a black label with white lettering; excepting the central one, which rested on scarlet velvet and had a red label inscribed in gold "13th May, 1909."

I gazed at this tiny head in its scarlet setting with shuddering fascination. It had a hideous little face; a broad, brutal face of the Tartar type; and the mop of gray-brown hair, so unhuman in color, and the bristling mustache that stood up like a cat's whiskers, gave it an aspect half animal, half devilish. I clapped the lid on the box, thrust it back on the shelf, and, plucking down the first volume of the "Archives," hurried out of the museum.

That night, when I had rounded up the day's work with a good dinner, I retired to my study, and, drawing an armchair up to the fire, opened the volume. It was a strange document. At first I was unable to perceive the relevancy of the matter to the title, for it seemed to be a journal of Challoner's private life; but later I began to see the connection, to realize, as Challoner had said, that the collection was nothing more than a visible commentary on and illustration of his daily activities.

The volume opened with an account of the murder of his wife and the circumstances leading up to it, written with a dry circumstantiality that was to me infinitely pathetic. It was the forced impassiveness of a strong man whose heart is breaking. There were no comments, no exclamations; merely a formal recital of facts, exhaustive, literal and precise. I need not quote it, as it only repeated the story he had told me, but I will commence my extract at the point where he broke off. The style, as will be seen, is that of a continuous narrative, apparently compiled from a diary; and, as it proceeds, marking the lapse of time, the original dryness of manner gives place to one more animated, more in keeping with the temperament of the writer.

"When I had buried my dear wife, I waited with some impatience to see what the police would do. I had no great expectations. The English police system is more adjusted to offences against property than to those against the person. Nothing had been stolen, so nothing could be traced; and the clues were certainly very slight. It soon became evident to me that the authorities had given the case up. They gave me no hope that the murderer would ever be identified; and, in fact, it was pretty obvious that they had written the case off as hopeless and ceased to interest themselves in it.

"Of course I could not accept this view. My wife had been murdered. The murder was without extenuation. It had been committed lightly to cover a paltry theft. Now, for murder, no restitution is possible. But there is an appropriate forfeit to be paid; and if the authorities failed to exact it, then the duty of its exaction devolved upon me. Moreover, a person who thus lightly commits murder as an incident in his calling is unfit to live in a community of human beings. It was clearly my duty as a good citizen to see that this dangerous person was eliminated.

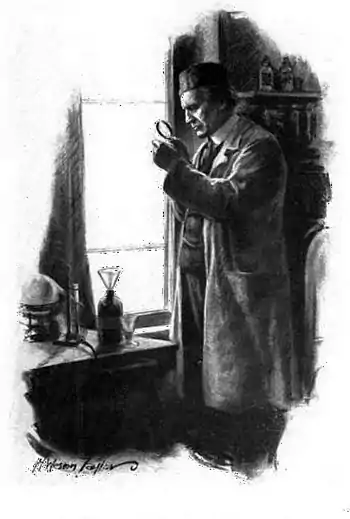

"This was well enough in theory, but its realization in practice presented considerable difficulties. The police had (presumably) searched for this person and failed to find him. How was I, untrained in methods of detection, to succeed where the experts had been baffled? I considered my resources. They consisted of a silver teapot and a salver which had been handled by the murderer and which, together, yielded a complete set of finger-prints, and the wisp of hair that I had taken from the hand of my murdered wife. It is true that the police also had finger-marked plate and the remainder of the hair and had been unable to achieve anything by their means; but the value of finger-impressions for the purposes of identification is not yet appreciated outside scientific circles.[1] I fetched the teapot and salver from the drawer in which I had secured them and examined them afresh. The teapot had been held in both hands and bore a full set of prints; and these were supplemented by the salver. For greater security I photographed the whole set of the finger-impressions and made platinotype prints which I filed for future reference. Then I turned my attention to the hair. I had already noticed that it was of a dull gray color, but now, when I came to look at it more closely, I found the color so peculiar that I took it to the window and examined it with a lens.

I took the hair to the window and examined it under a lens

"The result was a most startling discovery. It was ringed hair. The gray appearance was due, not to the usual mingling of white and dark hairs, but to the fact that each separate hair was marked by alternate rings of black and white. Now, variegated hairs are common enough in the lower animals which have a pattern on the fur. The tabby cat furnishes a familiar example. But in man the condition is infinitely rare; whence it was obvious that, with these hairs and the finger-prints, I had the means of infallible identification. But identification involves possession of the person to be identified. There was the difficulty. How was it to be overcome?

"Criminals are vermin. They have the typical characters of vermin; unproductive activity combined with disproportionate destructiveness. Just as a rat will gnaw his way through a Holbein panel, or shred up the Vatican Codex to make a nest, so the professional criminal will melt down priceless medieval plate to sell in lumps for a few shillings. The analogy is perfect.

"Now, how do we deal with vermin—with the rat, for instance?

"Do we go down his burrow and reason with him? Do we strive to elevate his moral outlook? Not at all. We induce him to come out. And when he has come out, we see to it that he doesn't go back. In short, we set a trap. And if the rat that we catch is not the one that we wanted, we set it again.

"Precisely. That was the method.

"My housemaid had absconded at the time of the murder; she was evidently an accomplice of the murderer. My cook had left on the same day, having conceived a not unnatural horror of the house. Since then I had made shift with a charwoman. But I should want a housemaid and a cook, and if I acted judiciously in the matter of references, I might get the sort of persons who would help my plans. For there are female rats as well as male.

"But there were certain preliminary measures to be taken. My physical condition had to be attended to. As a young man I was a first-class athlete, and even now I was strong and exceedingly active. But I must get into training and brush up my wrestling and boxing. Then I must fit up some burglar alarms, lay in a few little necessaries and provide myself with a suitable appliance for dealing with the 'catch.'

"This latter I proceeded with at once. To the end of a rod of rhinoceros horn about two feet long I affixed a knob of lead weighing two pounds. I covered the knob with a thickish layer of plaited horsehair, and over this fastened a covering of stout leather; and when I had fitted it with a wrist-strap it looked a really serviceable tool. Its purpose is obvious. It was an improved form of that very crude appliance, the sand-bag, which footpads use to produce concussion of the brain without fracturing the skull. I may describe it as a concussor.

"The preliminary measures were proceeding steadily. I had put in a fortnight's attendance at a gymnasium under the supervision of Professor Schneipp, the Bavarian Hercules; I had practiced the most approved 'knock-outs' known to my instructor, the famous pugilist, Melchizedeck Cohen (popularly known as 'Slimy' Cohen); I had given up an hour a day to studying the management of the concussor with the aid of a punching-ball; the alarms were ready for fixing, and I even had the address of an undoubtedly disreputable housemaid, when a most unexpected thing happened. I got a premature bite. A fellow actually walked into the trap without troubling me to set it.

"It befell thus. I had gone to bed rather early and fallen asleep at once, but about one o'clock I awoke with that unmistakable completeness that heralds a sleepless night. I lit my candlelamp and looked round for the book that I had been reading in the evening, and then I remembered that I had left it in the museum. Now that book had interested me deeply. It contained the only lucid description that I had met with of the Mundurucú Indians and their curious method of preserving the severed heads of their enemies; a method by which the head—after removal of the bones—was shrunk until it was no larger than a man's fist.

"I got up, and, taking my lamp and keys, made my way to the museum wing of the house, which opened out of the dining-room. I found the book, but, instead of returning immediately, lingered in the museum, looking about the great room and at the unfinished collection and gloomily recalling its associations. The museum was a gift from my wife. She had built it and the big laboratory soon after we were married and many a delightful hour we had spent in it together, arranging the new specimens in the cases. I did not allow her to work in the evil-smelling laboratory, but she had a collection of her own, of land and fresh-water shells (which were cleaner to handle than the bones); and I was pulling out some of the drawers in her cabinet, and, as I looked over the shells, thinking of the happy days when we rambled by the riverside or over furzy commons in search of them, when I became aware of faint sounds of movement from the direction of the dining-room.

"I stepped lightly down the corridor that led to the dining-room and listened. The door of communication was shut, but through it I could distinctly hear someone moving about and could occasionally detect the chink of metal. I ran back to the museum—my felt-soled bedroom slippers made no sound—and, taking the 'concussor' from the drawer in which I had concealed it, thrust it through the waist-band of my pajamas. Then I crept back to the door.

"The sounds had now ceased. I inferred that the burglar—for he could be none other—had gone to the pantry, where the plate-chest was kept. On this I turned the Yale latch and softly opened the door. It is my habit to keep all locks and hinges thoroughly oiled, and consequently the door opened without a sound. There was no one in the dining-room; but one burner of the gas was alight and various articles of silver plate were laid on the table, just as they had been when my wife was murdered. I drew the museum door to—I could not shut it because of the noise the spring latch would have made—and slipped behind a Japanese screen that stood near the dining-room door. I had just taken my place when a stealthy footstep approached along the hall. It entered the room and then there was a faint clink of metal. I peeped cautiously round the screen and looked on the back of a man who was standing by the table on which he was noiselessly depositing a number of spoons and forks and a candlestick. Although his back was towards me, a mirror on the opposite wall gave me a good view of his face; a wooden, expressionless face, such as I have since learned to associate with the English habitual criminal; the penal servitude face, in fact.

"He was a careful operator. He turned over each piece thoroughly, weighing it in his hand and giving especial attention to the hall-mark. And, as I watched him, the thought came into my mind that, perchance, this was the very wretch who had murdered my wife, come back for the spoil that he had then had to abandon. It was quite possible, even likely, and at the thought I felt my cheeks flush and a strange, fierce pleasure, such as I had never felt before, swept into my consciousness. I could have laughed aloud, but I did not. Also, I could have knocked him down with perfect ease as he stood, but I did not. Why did I not? Was it a vague, sporting sense of fairness? Or was it a catlike instinct impelling me to play with my quarry? I cannot say. Only I know that the idea of dealing him a blow from behind did not attract me.

"Presently he shuffled away (in list slippers) to fetch a fresh cargo. Then some ferociously playful impulse led me to steal out of my hiding-place and gather up a number of spoons and forks, a salt-cellar, a candlestick and an entrée-dish and retire again behind the screen. Then my friend returned with a fresh consignment; and as he was anxiously looking over the fresh pieces, I crept silently out at the other end of the screen, out of the open doorway and down the hall to the pantry. Here a lighted candle showed the plate-chest open and half empty, with a few pieces of plate on a side table. Quickly but silently I replaced in the chest the spoons and other pieces that I had collected, and then stole back to my place behind the screen and resumed my observations.

"My guest was quite absorbed in his task. He had a habit—common, I believe, among 'old lags'—of talking to himself; and very poor stuff his conversation was, though it was better than his arithmetic, as I gathered from his attempts to compute the weight of the booty. Anon, he retired for another consignment, and once more I came out and gathered up a little selection from his stock; and when he returned laden with spoil, I went off, as before, and put the articles back in the plate-chest.

"These manœuvres were repeated a quite incredible number of times. The man must have been an abject blockhead, as I believe most professional criminals are. His lack of observation was astounding. It is true that he began to be surprised and rather bewildered. He even noted that 'there seemed a bloomin' lot of 'em;' and the quality of his arithmetical feats and his verbal enrichments became, alike, increasingly lurid. I believe he would have gone on until daylight if I had not tried him too often with a Queen Anne teapot. It was that teapot, with its conspicuous urn design, that finally disillusioned him. I had just returned from putting it back in the chest for the third time when he missed it; and he announced the discovery with a profusion of perfectly unnecessary and highly inappropriate adjectives.

"'Naa, then!' he exclaimed truculently, 'where's that blimy teapot gone to? Hay? I put that there teapot down inside that there hontry-dish—and where's the bloomin' hontry? Bust me if that ain't gone to!'

"He stood by the table scratching his bristly head and looking the picture of ludicrous bewilderment. I watched him and meanwhile debated whether or not I should take the opportunity to knock him down. That was undoubtedly the proper course. But I could not bring myself to do it. A spirit of wild mischief possessed me; a strange, unnatural buoyancy and fierce playfulness that impelled me to play insane, fantastic tricks. It was a singular phenomenon. I seemed suddenly to have made the acquaintance of a hitherto unknown moiety of a dual personality.

"The burglar stood awhile, muttering idiotically, and then shuffled off to the pantry. I followed him out into the dark hall and, taking my stand behind a curtain, awaited his return. He came back presently, and, by the glimmer of light from the open door, I could see that he had the teapot and the 'hontry.' Now some previous tenant had fitted the dining-room door with two external bolts; I cannot imagine why; but the present circumstances suggested a use for them. As soon as the burglar was inside, I crept forward and quietly shut the door, shooting the top bolt.

"That roused my friend. He rushed at the door and shook it like a madman; he cursed with incredible fluency and addressed me in terms which it would be inadequate to describe as rude. Then I silently shot the bottom bolt and noisily drew back the top one. He thought I had unbolted the door, and when he found that I had not, his language became indescribable.

"There was a second door to the dining-room also opening into the hall at the farther end. My captive seemed suddenly to remember this, for he made a rush for it. But so did I; and, the hall being unobstructed by furniture, I got there first and shot the top bolt. He wrenched frantically at the handle and addressed me with strange and unseemly epithets. I repeated the manœuvre of pretending to unbolt the door, and smiled as I heard him literally dancing with frenzy inside. It seemed highly amusing at the time, though now, viewed retrospectively, it looks merely silly.

"Quite suddenly his efforts ceased and I heard him shuffle away. I returned to the other door, but he made no fresh attempt on it. I listened, and hearing no sound, bethought me of the open door of the museum. Probably he had gone there to look for a way out. This would never do. The plate I cared not a fig for, but the museum specimens were a different matter; and he might damage them from sheer malice.

"I unbolted the door, entered and shut it again, locking it on the inside and dropping the key into my pocket. I had just done so when he appeared at the museum door, eyeing me warily and unobtrusively slipping a knuckle-duster on his left hand. I had noted that he was not left-handed and drew my own conclusions as to what he meant to do with his right. We stood for some seconds facing each other and then he began to edge towards the door. I drew aside to let him pass and he ran to the door and turned the handle. When he found the door locked he was furious. He advanced threateningly with his left hand clenched, but then drew back. Apparently, my smiling exterior, coupled with my previous conduct, daunted him. I think he took me for a lunatic; in fact, he hinted as much in coarse, ill-chosen terms. But his vocabulary was very limited, though quaint.

"We exchanged a few remarks and I could see that he did not like the tone of mine. The fact is that the sight of the knuckle-duster had changed my mood. I no longer felt playful. He had recalled me to my original purpose. He expressed a wish to leave the house and to know 'what my game was.' I replied that he was my game and that I believed that I had bagged him, whereupon he rushed at me and aimed a vicious blow at my head with his armed left fist, which, if it had come home, would have stretched me senseless. But it did not. I guarded it easily and countered him so that he staggered back gasping.

"That made him furious. He came at me like a wild beast, with his mouth open and his armed fist flourished aloft as if he would annihilate me. I tried to deal with him by the methods of Mr. Slimy Cohen, but it was useless. He was no boxer and he had a knuckle-duster. Consequently we grabbed one another like a pair of monkeys and sought to inflict unorthodox injuries. He struggled and writhed and growled and kicked and even tried to bite; while I kept, as far as I could, control of his wrists and waited my opportunity. It was a most undignified affair. We staggered to and fro, clawing at one another; we gyrated round the room in a wild, unseemly waltz; we knocked over the chairs, we bumped against the table, we banged each other's heads against the walls; and all the time, as my adversary growled and showed his teeth like a savage dog, I was sensible of a strange feeling of physical enjoyment such as one might experience in some strenuous game. I seemed to have acquired a new and unfamiliar personality.

"But the knuckle-duster was a complication; for it was his right hand that I had to watch; and yet I could not afford to free for an instant his left, armed as it was with that shabbiest of weapons. Hence I hung on to his wrists while he struggled to wrench them free, and we pulled one another backwards and forwards and round and round in the most absurd and amateurish manner, each trying to trip the other up and failing at every attempt. At last, in the course of our gyrations, we bumped through the open door into the passage leading to the museum; and here we came down together with a crash that shook the house.

"As ill luck would have it, I was underneath; but, in spite of the shock of the fall, I still managed to keep hold of his wrists, though I had some trouble to prevent him from biting my hands and face. So our position was substantially unchanged, and we were still wriggling chaotically when a hasty step was heard descending the stairs. The burglar paused for an instant to listen and then, with a sudden effort, wrenched away his right hand, which flew to his hip-pocket and came out grasping a small revolver. Instantly I struck up with my left and caught him a smart blow under the chin, which dislodged him; and as he rolled over there was a flash and a report, accompanied by the shattering of glass and followed immediately by the slamming of the street door. I let go his left hand, and, rising to my knees, grabbed the revolver with my own left, while, with my right, I whisked out the concussor and aimed a vigorous blow at the top of his head. The padded weight came down without a sound—excepting the click of his teeth—and the effect was instantaneous. I rose, breathing quickly and eminently satisfied with the efficiency of my implement until I noticed that the unconscious man was bleeding slightly from the ear; which told me that I had struck too hard and fractured the base of the skull.

"However, my immediate purpose was to ascertain whether this was or was not the man whom I wanted. In the passage it was too dark to see either his finger-tips or the minute texture of his hair; but my candle-lamp, with its parabolic reflector, would give ample light. I ran through into the museum, where it was still burning, and, catching it up, ran back with it; but I had barely reached the prostrate figure when I heard someone noisily opening the street door with a latch-key. The charwoman had returned, no doubt, with the police.

"I am rather obscure as to what I meant to do. I think I had no definitely-formed intentions but acted more or less automatically, impelled by the desire to identify the burglar. What I did was to close the museum door very quietly, with the aid of the key, unlock the dining-room door and open it.

"A police sergeant, a constable and a plain-clothes officer entered and the charwoman lurked in the dark background.

"'Have they got away?' the sergeant demanded.

"'There was only one,' I said.

"At this the officers bustled away and I heard them descending to the basement. The charwoman came in and looked gloatingly at my battered countenance, which bore memorials of every projecting corner of the room.

"'It's a pity you come down, sir,' said she. 'You might have been murdered same as what your poor lady was. It's better to let them sort of people alone. That's what I say. Let 'em alone and they'll go home, as the sayin' is.'

"There was considerable truth in these observations, especially the last. I acknowledged it vaguely, while the woman cast fascinated glances round the disordered room. Then two of the officers returned and took up the enquiry to an accompaniment of distant police whistles from the back of the house.

"'I needn't ask if you saw the man,' said the plain-clothes officer, with a faint grin.

"'No, you're right,' said the sergeant. 'He set upon you properly, sir. Seems to have been a lively party.' He glanced round the room and added: 'Fired a pistol, too, your housekeeper tells me.'

"I nodded at the shattered mirror but made no comment, and the officer, remarking that I 'seemed a bit shaken up,' proceeded with his investigations. I watched the two men listlessly. I was not much interested in them. I was thinking of the man on the other side of the museum door and wondering if he had ringed hair.

"Presently the plain-clothes officer made a discovery. 'Hallo,' said he, 'here's a carpet bag.' He drew it out from under the table and hoisted it up under the gaslight to examine it; and then he burst into a loud and cheerful laugh.

"'What's up?' said the sergeant.

"'Why, it's Jimmy Archer's bag.'

"'No!'

"'Fact. He showed it to me himself. It was given to him by the 'Discharged Prisoners' Aid Society' to carry his tools in. Ha! Ha! O Lord!'

"The sergeant examined the bag with an appreciative grin, which broadened as his colleague lifted out a brace, a pad of bits, a folding jimmy and a few other trifles. I made a mental note of the burglar's name, and then my interest languished again. The two officers looked over the room together, tried the museum door and noted that it had not been tampered with; turned over the plate and admonished me on the folly of leaving it so accessible; and finally departed with the promise to bring a detective-inspector in the morning, and meanwhile to leave a constable to guard the house.

"I would gladly have dispensed with that constable, especially as he settled himself in the dining-room and seemed disposed to converse, which I was not. His presence shut me off from the museum. I could not open the door, for the burglar was lying just inside. It was extremely annoying. I wanted to make sure that the man was really dead, and, especially, I wanted to examine his hair and to compare his finger-prints with the set that I had in the museum. However, it could not be helped. Eventually I took my candle-lamp from the sideboard and went up to bed, leaving the constable seated in the easy-chair with a box of cigars, a decanter of whiskey and a siphon of Apollinaris at his elbow.

"I remained awake a long time cogitating on the situation. Was the man whom I had captured the right man? Had I accomplished my task, and was I now at liberty to 'determine,' as the lawyers say, the lease of my ruined life? That was a question which the morning light would answer; and meanwhile one thing was clear: I had fairly committed myself to the disposal of the dead burglar. I could not produce the body now; I should have to get rid of it as best I could.

"Of course, the problem presented no difficulty. There was a fire-clay furnace in the laboratory in which I had been accustomed to consume the bulky refuse of my preparations. A hundredweight or so of anthracite would turn the body into undistinguishable ash; and yet—well, it seemed a wasteful thing to do. I have always been rather opposed to cremation, to the wanton destruction of valuable anatomical material. And now I was actually proposing, myself, to practice that which I had so strongly deprecated. I reflected. Here was a specimen delivered at my very door, nay, into the very precincts of my laboratory. Why should I destroy it? Could I not turn it to some useful account in the advancement of science?

"I turned this question over at length. Here was a specimen. But a specimen of what? I am no mere curio-monger, no collector of frivolous and unmeaning trifles. A specimen must illustrate some truth. Now what truth did this specimen illustrate? The question, thus stated, brought forth its own answer in a flash.

"Criminal anthropology is practically an unillustrated science. A few paltry photographs, a few mouldering skulls of forgotten delinquents (such as that of Charlotte Corday), form the entire material on which criminal anthropologists base their unsatisfactory generalizations. But here was a really authentic specimen with a traceable life-history. It ought not to be lost to science. And it should not be.

"Presently my thoughts took a new turn. I had been deeply interested in the account that I had read of the ingenious method by which the Mundurucús used to preserve the heads of their slain enemies. The book was unfortunately still in the museum, but I had read the account through, and now recalled it. The Mundurucú warrior, when he had killed an enemy, cut off his head with a broad bamboo knife and proceeded to preserve it thus: First he soaked it for a time in some non-oxidizable vegetable oil; then he extracted the bone and the bulk of the muscles somewhat as a bird-stuffer extracts the body from the skin. He then filled up the cavity with hot pebbles and hung the preparation up to dry.

"By repeating the latter process many times, a gradual and symmetrical shrinkage was produced until the head had dwindled to the size of a man's fist or even smaller, leaving the features, however, practically unaltered. Finally he decorated the little head with bright-colored feathers—the Mundurucús were very clever at feather work—and fastened the lips together with a string, by which the head was suspended from the eaves of his hut or from the beams of the council house.

"It was highly ingenious. The question was whether heads so preserved would be of any use for the study of facial characters. I had intended to get a dead monkey from Jamrach's and experiment in the process. But now it seemed that the monkey would be unnecessary if only the preparation could be produced without injuring the skull; and I had no doubt that, with due care and skill, it could.

"At daybreak I went down to the dining-room. The policeman was dozing in his chair; there was a good deal of cigar-ash about, and the whiskey-decanter was less full than it had been, though not unreasonably so. I roused up the officer and dismissed him with a final cigar and what he called an 'eye-opener'—about two fluid-ounces. When he had gone I let myself into the museum lobby. The burglar was quite dead and beginning to stiffen. That was satisfactory; but was he the right man? I snipped off a little tuft of hair and carried it to the laboratory where the microscope stood on the bench under its bell-glass. I laid one or two hairs on a slide with a drop of glycerine and placed the slide on the stage of the microscope. Now was the critical moment. I applied my eye to the instrument and brought the objective into focus.

"Alas! The hairs were uniformly colored with brown pigment! He was the wrong man.

"It was very disappointing. I really need not have killed him, though under the circumstances there was nothing to regret on that score. He would not have died in vain. Alive he was merely a nuisance and a danger to the community, whereas in the form of museum preparations he might be of considerable public utility.

"Under the main bench in the laboratory was a long cupboard containing a large zinc-lined box or tank in which I had been accustomed to keep the specimens which were in process of preparation. I brought the burglar into the laboratory and deposited him in the tank, shutting the air-tight lid and securing it with a padlock. For further security I locked the cupboard, and, when I had washed the floor of the lobby and dried it with methylated spirit, all traces of the previous night's activities were obliterated. If the police wanted to look over the museum and laboratory, they were now quite at liberty to do so.

"I have mentioned that, during the actual capture of this burglar, I seemed to develop an entirely alien personality. But the change was only temporary, and I had now fully recovered my normal temperament, which is that of a careful, methodical and eminently cautious man. Hence, as I took my breakfast and planned out my procedure, an important fact made itself evident. I should presently have in my museum a human skeleton which I should have acquired in a manner not recognized by social conventions or even by law. Now, if I could place myself in a position to account for that skeleton in a simple and ordinary way, it might, in the future, save inconvenient explanations.

"I decided to take the necessary measures without delay, and accordingly, after a rather tedious interview with the detective-inspector (whom I showed over the entire house, including the museum and laboratory), I took a cab to Great St. Andrew Street, Seven Dials, where resided a well-known dealer in osteology. I did not, of course, inform him that I had come to buy an understudy for a deceased burglar. I merely asked for an articulated skeleton, to stand and not to hang (hanging involves an unsightly suspension ring attached to the skull). I looked over his stock with a steel measuring-tape in my hand, for a skeleton of about the right size—sixty-three inches—but I did not mention that size was a special object. I told him that I wished for one that would illustrate racial characters, at which he smiled—as well he might, knowing that his skeletons were mostly built up of assorted bones of unknown origin.

"I selected a suitable skeleton, paid for it, (five pounds) and took care to have a properly drawn invoice, describing the goods and duly dated and receipted. I did not take my purchase away with me; but it arrived the same day, in a funeral box, which the detective-inspector, who happened to be in the house at the time, kindly assisted me to unpack.

"My next proceeding was to take a set of photographs of the deceased, including three views of the face, a separate photograph of each ear, and two aspects of the hands. I also took a complete set of finger-prints. Then I was ready to commence operations in earnest."

The rest of Challoner's narrative relating to Number One is of a highly technical character and not very well suited to the taste of lay readers. The final result will be understood by the following quotation from the museum catalogue:

"Specimens Illustrating Criminal Anthropology.

"Series A. Osteology.

"1. Skeleton of burglar, aged 37. ♂. Height 63 inches. (James Archer.)

"This specimen was of English parentage, was a professional burglar, a confirmed recidivist, and—since he habitually carried fire-arms—a potential homicide. His general intelligence appears to have been of a low order, his manual skill very imperfect (he was a gas-fitter by trade but never regularly employed). He was nearly illiterate and occasionally but not chronically alcoholic.

"Cranial capacity 1594 cc. Cephalic index 76.8.

"For finger-prints see Album D 1, p. 1. For facial characters see Album E 1, pp. 1, 2 and 3, and Series B (dry, reduced preparations). Number 1."

I closed the two volumes—the Catalogue and the Archives—and meditated on the amazing story that they told in their unemotional, matter-of-fact style. Was poor Challoner mad? Had he an insane obsession on the subject of crime and criminals? Or was he, perchance, abnormally sane, if I may use the expression? That his outlook was not as other men's was obvious. Was it a rational outlook or that of a lunatic?

I cannot answer the question. Perhaps a further study of his Archives may throw some fresh light on it.

- ↑ The narrative seems to have been written in 1890.—L. W.