406

Examination of a Chambered Long Barrow

constructed at the eastern end;[1] and, referring to North Wiltshire and Somersetshire, he observes, that in those counties where stone abounds we frequently find a cromlech, or cistvaen, at the east end, which, in general, is the highest part of the barrow.[2] In a paper in the Archæologia, Sir Richard proposes to denominate this species of tumulus the "stone barrow;" observing, however, that it differs from the long barrow, "not in its external, but its internal construction. None of this kind," he proceeds, "occurred to me during my researches in South Wiltshire, for the material of stone, of which they were partly formed, was wanting. But some I have found in North Wiltshire, and will be described in my Ancient History of that district."[3] In 1816 the zealous baronet assisted in the exploration of the remarkable chambered tumulus at Stoney Littleton in Somersetshire, which elicited these remarks; and, in 1821, of that at Littleton Drew;[4] but, with the last exception, he made no excavations in the long stone barrows of North Wiltshire.

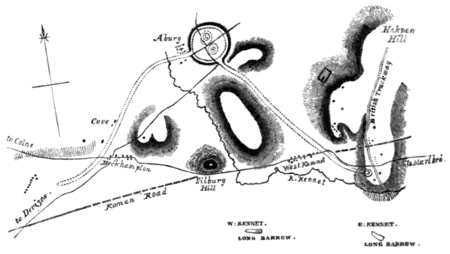

fig. 1. Plan showing the position of the Long Barrow at West Kennet, in relation to the circles at Avebury, Silbury Hill, &c.

- ↑ Ancient Wilts, vol. ii. pp 99, 116.

- ↑ Ancient Wilts, Roman Era, p. 102.

- ↑ Archæologia, vol. xix. p. 43. Account of a Stone Barrow at Stoney Littleton. The Chambered Tumulus at Uley, Gloucestershire, described by the writer in the Archæological Journal, vol. xi. p. 315, closely resembles that at Stoney Littleton.

- ↑ Gentleman's Magazine, vol. xcii. Feb. 1822, p. 160. See Wilts Archæological and Natural History Magazine, 1856, vol. iii. p. 164, for the completed account, by the writer, of this long barrow, with its contained cists and the remarkable trilith still standing at its east end.