CHAP. IIII.

That the Earth moves circularly.

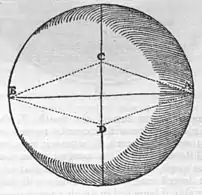

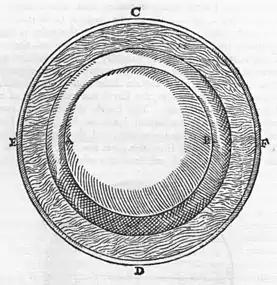

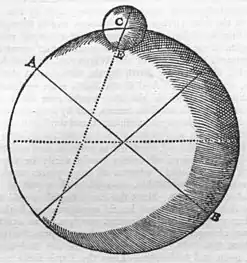

So also it would move in any other great circle if it could be free; as in the declination instrument, a circular motion takes place in the meridian (if there were no variation), or, if there should be some variation, in a great circle drawn from the Zenith through the point of variation on the horizon. And that circular motion of the magnet to its own just and natural position shows that the whole Earth is fitted and adapted, and is sufficiently furnished with peculiar forces for diurnal circular motion. I omit what Peter Peregrinus[248] constantly affirms, that a terrella suspended above its poles on a meridian moves circularly, making an entire revolution in 24 hours: which, however, it has not happened to ourselves as yet to see; and we even doubt this motion on account of the weight of the stone itself, as well as because the whole Earth, as she is moved of herself, so also is she propelled by other stars: and this does not happen in proportion (as it does in the terrella) in every part. The Earth is moved by her own primary form and natural desire, for the conservation, perfection, and ordering of its parts, toward things more excellent: and this is more likely than that the fixed stars, those luminous globes, as well as the Wanderers, and the most glorious and divine Sun, which are in no way aided by the Earth, or renewed, or urged by any virtue therein, should circulate aimlessly around the Earth, and that the whole heavenly host should repeat around the Earth courses never ending and of no profit whatever to the stars. The Earth, then, which by some great necessity, even by a virtue innate, evident, and conspicuous, is turned circularly about the Sun, revolves; and by this motion it rejoices in the solar virtues and influences, and is strengthened by its own sure verticity, that it should not rovingly revolve over every region of the heavens. The Sun (the chief agent in nature) as he forwards the courses of the Wanderers, so does he prompt this turning about of the Earth by the diffusion of the virtues of his orbes, and of light. And if the Earth were not made to spin with a diurnal revolution, the Sun would ever hang over some determinate part with constant beams, and by long tarriance would scorch it, and pulverize it, and dissipate it, and the Earth would sustain the deepest wounds; and nothing good would issue forth; it would not vegetate, it would not allow life to animals, and mankind would perish. In other parts, all things would verily be frightful and stark with extreme cold; whence all high places would be very rough, unfruitful, inaccessible, covered with a pall of perpetual shades and eternal night. Since the Earth herself would not choose to endure this so miserable and horrid appearance on both her faces, she, by her magnetick astral genius, revolves in an orbit, that by a perpetual change of light there may be a perpetual alternation of things, heat and cold, risings and settings, day and night, morn and eve, noon and midnight. Thus the Earth seeks and re-seeks the Sun, turns away from him and pursues him, by her own wondrous magnetick virtue. Besides, it is not only from the Sun that evil would impend, if the Earth were to stay still and be deprived of solar benefit; but from the Moon also serious dangers would threaten. For we see how the ocean rises and swells beneath certain known positions of the Moon: And if there were not through the daily rotation of Earth a speedy transit of the Moon, the flowing sea would be driven above its level into certain regions, and many shores would be overwhelmed with huge waves. In order then that Earth may not perish in various ways, and be brought to confusion, she turns herself about by magnetick and primary virtue: and the like motions exist also in the rest of the Wanderers, urged specially by the movement and light of other bodies. For the Moon also turns herself about in a monthly course, to receive in succession the Sun's beams in which she, like the Earth, rejoices, and is refreshed: nor could she endure them for ever on one particular side without great harm and sure destruction. Thus each one of the moving globes is for its own safety borne in an orbit either in some wider circle, or only by a rotation of its body, or by both together. But it is ridiculous for a man a philosopher to suppose that all the fixed stars and the planets and the still higher heavens revolve to no other purpose, save the advantage of the Earth. It is the Earth, then, that revolves, not the whole heaven, and this motion gives opportunity for the growth and decrease of things, and for the generating of things animate, and awakens internal heat for the bringing of them to birth. Whence matter is quickened for receiving forms; and from the primary rotation of the Earth natural bodies have their primary impetus and original activity. The motion then of the whole Earth is primary, astral, circular, around its own poles, whose verticity arises on both sides from the plane of the æquator, and whose vigour is infused into opposite termini, in order that the Earth may be moved by a sure rotation for its good, the Sun also and the stars helping its motion. But the simple straight motion downwards of the Peripateticks is a motion of weight, a motion of the aggregation of disjoined parts, in the ratio of their matter, along straight lines toward the body of the Earth: which lines tend the shortest way toward the centre. The motions of disjoined magnetical parts of the Earth, besides the motion of aggregation, are coition, revolution, and the direction of the parts to the whole, for harmony of form, and concordancy.

The page and line references given in these notes are in all cases first to the Latin edition of 1600, and secondly to the English edition of 1900.

246 ^ Page 221, line 10. Page 221, line 11. poli verè oppositi sint.—For verè, the 1628 and 1633 editions read rectæ. All editions read sint, though sunt seems to make better sense.

247 ^ Page 223, line 7. Page 223, line 8. ad telluris conformitatem.—The word conformitas is unknown in classical Latin.

248 ^ Page 223, line 16. Page 223, line 17. Omitto quod Petrus Peregrinus constanter affirmat, terrellam super polos suos in meridiano suspensam, moveri circulariter integrâ revolutione 24 horis: Quod tamen nobis adhuc videre non contingit; de quo motu etiam dubitamus.

This statement that a spherical loadstone pivotted freely with its axis parallel to the earth's axis will of itself revolve on its axis once a day under the control of the heavens, thus superseding clocks, is to be found at the end of chap. x. of Peregrinus's Epistola De Magnete (Augsb., 1537).

Gilbert, who doubted this experiment because of the stone's own weight is taken to task by Galileo, in the third of his Dialogues, for his qualified admission.

"I will speak of one particular, to which I could have wished that Gilbert had not lent an ear; I mean that of admitting, that in case a little Sphere of Loadstone might be exactly librated, it would revolve in it self; because there is no reason why it should do so" (p. 376 of Salusbury's Mathematical Collections, London, 1661). The Jesuit Fathers who followed Gilbert, but rejected his Copernican ideas, pounced upon this pseudo-experiment, as though by disproving it they had upset the Copernican theory.