CHAP. IX.

Figures illustrating direction and showing varieties

of rotations.

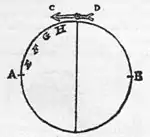

Figures illustrating magnetick directions in a right sphere[208] of stone, and in the right sphere of the earth, as well as the polar directions to the perpendicular of the poles. All these cusps have been touched by the pole A; all the cusps are turned toward A, excepting that one which is repelled by B.

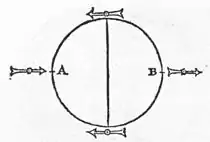

Figures illustrating horizontal directions above the body of a loadstone. All the cusps that have been made southern by rubbing on the boreal pole, or some place round the northern pole A, turn toward the pole A, and turn away from the southern pole B, toward which all the crosses look. I call the direction horizontal, because it is arranged along the plane of the horizon; for nautical and * horological instruments are so constructed that the iron hangs or is supported in æquilibrium on the point of a sharp pin, which prevents the dipping of the versorium, about which we intend to speak later. And in this way it is of the greatest use to man, indicating and distinguishing all the points of the horizon and the winds. Otherwise on every oblique sphere (whether of stone or the earth) versoria and all magnetick substances would have a dip by their own nature below the horizon; and at the poles the directions would be perpendicular, which appears in our discussion On Declination.

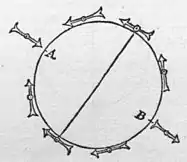

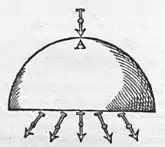

A round stone (or terrella) cut in two at the æquator; and all the cusps have been touched by the pole A. The points at the centre of the earth, and between the two parts of the terrella which has been cut in two through the plane of the æquator, are directed as in the present[209] diagram. This would also happen in the same way if the division of the stone were through the plane of a tropick, and the mutual separation of the divided parts and the interval between them were the same as before, when the loadstone was divided through the plane of the æquator, and the parts separated. For the cusps are repelled by C, are attracted by D; and the versoria are parallel, the poles or the verticity in both ends mutually requiring it.

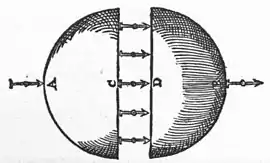

Half a terrella by itself and its directions, unlike the directions * of the two parts close to one another as shown in the figure above. All the cusps have been touched by A; all the crosses below except the middle one tend toward the loadstone, not straight, but obliquely; because the pole is in the middle of the plane which before was the plane of the æquator. All cusps touched by places distant from the pole move toward the pole (exactly the same as if they had been rubbed upon the pole itself), not toward the place where they were rubbed, wherever that may have been in the undivided stone in some latitude between the pole and the æquator. And for this reason there are only two distinctions of regions, northern and southern, in the terrella, just as in the general terrestrial globe, and there is no eastern nor western place; nor are there any eastern or western regions, rightly speaking; but they are names used in respect of one another toward the eastern or western part of the sky. Wherefore it does not appear that Ptolemy did rightly in his Quadripartitum, making eastern and western districts and provinces, with which he improperly connects the planets, whom the common crowd of philosophizers and the superstitious soothsayers follow.

208 ^ Page 134, line 22. Page 134, line 25. in rectâ sphærâ.—The meaning of the terms a right or direct sphere, an oblique sphere and a parallel sphere are explained by Moxon on pages 29 to 31 of his book A Tutor to Astronomy and Geography (Lond., 1686):

"A Direct Sphere hath both the Poles of the World in the Horizon ... It is called a Direct Sphere, because all the Celestial Bodies, as Sun, Moon, and Stars, &c. By the Diurnal Motion of the Primum Mobile, ascend directly Above, and descend directly Below the Horizon. They that Inhabit under the Equator have the Sphere thus posited."

"An Oblique Sphere hath the Axis of the World neither Direct nor Parallel to the Horizon, but lies aslope from it."

"A Parallel Sphere hath one Pole of the World in the Zenith, the other in the Nadir, and the Equinoctial Line in the Horizon."

209 ^ Page 136, line 1. Page 136, line 1. præsenti.—The editions of 1628 and 1633 read sequenti, to suit the altered position of the figure.