CHAP. XII.

In what way Verticity exists in any Iron that has

been smelted though not excited by a lodestone.

The page and line references given in these notes are in all cases first to the Latin edition of 1600, and secondly to the English edition of 1900.

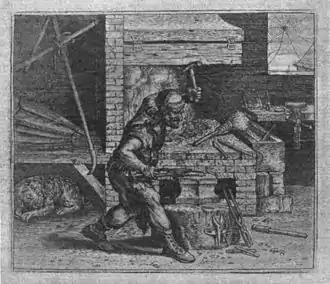

211 ^ Page 139. There is a curious history to this picture of the blacksmith in his smithy striking the iron while it lies north and south, and so magnetizing it under the influence of the earth's magnetism. Woodcuts containing human figures are comparatively rare in English art of the sixteenth century; a notable exception being Foxe's Acts and Monuments with its many crude cuts of martyrdoms. The artist who prepared this cut of the smith took the design from an illustrated book of Fables by one Cornelius Kiliani or Cornelius van Kiel entitled Viridarium Moralis Philosophiæ, per Fabulas Animalibus brutis attributas traditæ, etc. (Coloniæ, 1594). This rare work, of which there is no copy in the British Museum, is illustrated by some 120 fine copper-plate etchings printed in the text. On p. 133 of this work is an etching to illustrate the fable Ferrarii fabri et canis, representing the smith smiting iron on the anvil, whilst his lazy dog sleeps beneath the bellows. The cut on p. 139 of Gilbert gives, as will be seen by a comparison of the pictures just the same general detail of forge and tools; but the position of the smith is reversed right for left, the dog is omitted, and the words Septrenio and Auster have been added.

In the Stettin edition of 1628 the picture has again been turned into a copper-plate etching separately printed, is reversed back again left for right, while a compass-card is introduced in the corner to mark the north-south direction.

In the Stettin edition of 1633 the artist has gone back to Kiliani's original plate, and has re-etched the design very carefully, but reversing it all right for left. As in the London version of 1600, the dog is omitted, and the words Septentrio and Auster are added. Some of the original details—for example, the vice and one pair of pincers—are left out, but other details, for instance, the cracks in the blocks that support the water-tub, and the dress of the blacksmith, are rendered with slavish fidelity.

It is perhaps needless to remark that the twelve copper-plate etchings in the edition of 1628, and the twelve completely different ones in that of 1633, replace certain of the woodcuts of the folio of 1600. For example, take the woodcut on p. 203 of the 1600 edition, which represents a simple dipping-needle made by thrusting a versorium through a bit of cork and floating it, immersed, in a goblet of water. In the 1633 edition this appears, slightly reduced, as a small inserted copper-plate, with nothing added; but in the 1628 edition it is elaborated into a full-page plate (No. xi.) representing the interior, with shelves of books, of a library on the floor of which stands the goblet—apparently three feet high—with a globe and an armillary sphere; while beside the goblet, with his back to the spectator, is seated an aged man, reading, in a carved armchair. This figure and the view of the library are unquestionably copied—reversed—from a well-known plate in the work Le Diverse & Artificiose Machine of Agostino Ramelli (Paris, 1558).

In the Emblems of Jacob Cats (Alle de Wercken, Amsterdam, 1665, p. 65) is given an engraved plate of a smith's forge, which is also copied—omitting the smith—from Kiliani's Viridarium.

212 ^ Page 140, line 2.. Page 140, line 2. præcedenti.—This is so spelled in all editions, though the sense requires præcedente.

213 ^ Page 141, line 21. Page 141, line 24. quod in epistolâ quâdam Italicâ scribitur.—The tale told by Filippo Costa of Mantua about the magnetism acquired by the iron rod on the tower of the church of St. Augustine in Rimini is historical. The church was dedicated to St. John, but in the custody of the Augustinian monks. The following is the account of it given by Aldrovandi, Musæum Metallicum (1648, p. 134), on which page also two figures of it are given:

"Aliquando etiam ferrum suam mutat substantiam, dum in magnetem conuertitur, & hoc experientia constat, nam Arimini supra turrim templi S. Ioannis erat Crux a baculo ferreo ponderis centum librarum sustentata, quod tractu temporis adeò naturam Magnetis est adeptum, vt, illivs instar, ferrum traheret: hinc magna admiratione multi tenentur, qua ratione ferrum, quod est metallum in Magnetem, qui est lapis transmutari possit; Animaduertendum est id à maxima familiaritate & sympathia ferri, & magnetis dimanare cum Aristoteles in habentibus symbolum facilem transitum semper admiserit. Hoc in loco damus imaginem frusti ferri in Magnetem transmutati, quod clarissimo viro Vlyssi Aldrouando Iulius Caesar Moderatus diligens rerum naturalium inquisitor communicauit; erat hoc frustum ferri colore nigro, & ferrugineo, crusta exteriori quodammodo albicante." And further on p. 557.

"Preterea id manifestissimum est; quoniam Arimini, in templo Sancti Ioannis, fuit Crux ferrea, quæ tractu temporis in magnetem conuersa est, & ab vno latere ferrum trahebat, & ab altero respuebat." See also Sir T. Browne's Pseudodoxia Epidemica (edition of 1650, p. 48), and Boyle's tract, Experiments and Notes about the Mechanical Production of Magnetism (London, 1676, p. 12).

Another case is mentioned in Dr. Martin Lister's A Journey to Paris (Lond., 1699, p. 83). "He [Mr. Butterfield] shewed us a Loadstone sawed off that piece of the Iron Bar which held the Stones together at the very top of the Steeple of Chartres. This was a thick Crust of Rust, part of which was turned into a strong Loadstone, and had all the properties of a Stone dug out of the Mine. Mons. de la Hire has Printed a Memoir of it; also Mons. de Vallemont a Treatise. The very outward Rust had no Magnetic Virtue, but the inward had a strong one, as to take up a third part more than its weight unshod." Gassendi and Grimaldi have given other cases.

Other examples of iron acquiring strong permanent magnetism from the earth are not wanting. The following is from Sir W. Snow Harris's Rudimentary Magnetism (London, 1872, p. 10).

"In the Memoirs of the Academy of Sciences for 1731, we find an account of a large bell at Marseilles having an axis of iron: this axis rested on stone blocks, and threw off from time to time great quantities of rust, which, mixing with the particles of stone and the oil used to facilitate the motion, became conglomerated into a hardened mass: this mass had all the properties of the native magnet. The bell is supposed to have been in the same position for 400 years."

214 ^ Page 142, line 13. Page 142, line 15. tunc planetæ & corpora cœlestia.—Gilbert's extraordinary detachment from all metaphysical and ultra-physical explanations of physical facts, and his continual appeal to the test of experimental evidence, enabled him to lift the science of the magnet out of the slough of the dark ages. This passage, however, reveals that he still gave credence to the nativities of judicial Astrology, and to the supposed influence of the planets on human destiny.