CHAP. III.

The Loadstone has parts distinct in their natural

power, & poles conspicuous for their property.

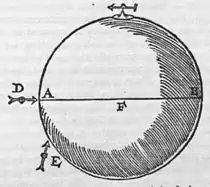

On the stone A B the versorium is placed in such a way that the versorium may remain in equilibrium: you will mark with chalk the course of the iron when at rest: Move the instrument to another spot, and again make note of the direction and aspect: do the same thing in several places, and from the concurrence of the lines of direction you will find one pole at the point A, the other at B. A versorium placed near the stone also indicates the true pole; when at right angles it eagerly beholds the stone and seeks the pole itself directly, and is turned in a straight line through the axis to the centre of the stone. For instance, the versorium D faces toward A and F, the pole and centre, whereas E does not exactly respect * either the pole A or the centre F[64]. A bit of rather fine iron wire, of the length of a barley-corn, is placed on the stone, and is moved over the regions and surface of the stone, until it rises to the perpendicular[65]: for it stands erect at the actual pole, whether Boreal or austral; the further from the pole, the more it inclines from the vertical. The poles thus found you shall mark with a sharp file or gimlet.

The page and line references given in these notes are in all cases first to the Latin edition of 1600, and secondly to the English edition of 1900.

61 ^ Page 12, line 30. Page 12, line 35. integtum appears to be a misprint for integrum, which is the reading of editions 1628 and 1633.

62 ^ Page 13, line 4. Page 13, line 3. μικρόγη seu Terrella. Although rounded loadstones had been used before Gilbert's time (see Peregrinus, p. 3 of Augsburg edition of 1558, or Baptista Porta, p. 194, of English edition of 1658), Gilbert's use of the spherical loadstone as a model of the globe of the earth is distinctive. The name Terrella remained in the language. In Pepys's Diary we read how on October 2, 1663, he "received a letter from Mr. Barlow with a terella." John Evelyn, in his Diary, July, 1655, mentions a "pretty terella with the circles and showing the magnetic deviations."

A Terrella, 4½ inches in diameter, was presented in 1662 by King Charles I. to the Royal Society, and is still in its possession. It was examined in 1687 (see Phil. Transactions for that year) by the Society to see whether the positions of its poles had changed.

In Grew's Catalogue and Description of the Rarities belonging to the Royal Society and preserved at Gresham College (London, 1681, p. 364) is mentioned a Terrella contrived by Sir Christopher Wren, with one half immersed in the centre of a plane horizontal table, so as to be like a Globe with the poles in the horizon, having thirty-two magnet needles mounted in the margin of the table to show "the different respect of the Needle to the several Points of the Loadstone."

In Sir John Pettus's Fleta Minor, London, 1683, in the Dictionary of Metallick Words at the end, under the word Loadstone occurs the following passage:

"Another piece of Curiosity I saw in the Hands of Sir William Persal (since Deceased also) viz., a Terrella or Load-stone, of little more than 6 Inches Diameter, turned into a Globular Form, and all the Imaginery Lines of our Terrestrial Globe, exactly drawn upon it: viz. the Artick and Antartick Circles, the two Tropicks, the two Colures, the Zodiack and Meridian; and these Lines, and the several Countryes, artificially Painted on it, and all of them with their true Distances, from the two Polar Points, and to find the truth of those Points, he took two little pieces of a Needle, each of about half an Inch in length, and those he laid on the Meridian line, and then with Brass Compasses, moved one of them towards the Artick, which as it was moved, still raised it self at one end higher and higher, keeping the other end fixt to the Terrella; and when it had compleated it Journy to the very Artick Points, it stood upright upon that Point; then he moved the other piece of Needle to the Antartick Point, which had its Elevations like the other, and when it came to the Point, it fixt it self upon that Point, and stood upright, and then taking the Terrella in my Hand, I could perfectly see that the two pieces of Needles stood so exactly one against the other, as if it had been one intire long Needle put through the Terrella, which made me give credit to those who held, That there is an Astral Influence that darts it self through the Globe of Earth from North to South (and is as the Axel-Tree to the Wheel, and so called the Axis of the World) about which the Globe of the Earth is turned, by an Astral Power, so as what I thought imaginary, by this Demonstration, I found real."

63 ^ Page 13, line 20. Page 13, line 22. The editions of 1628 and 1633 give a different woodcut from this: they show the terrella lined with meridians, equator, and parallels of latitude: and they give the compass needle, at the top, pointing in the wrong direction.

64 ^ Page 14, line 3. Page 14, line 3. The Berlin "facsimile" reprint omits the asterisk here.

65 ^ Page 14, line 5. Page 14, line 6. erectus altered in ink in the folio to erecta. But erectus is preserved in editions 1628 and 1633. In Cap. IIII., on p. 14, both these Stettin editions insert an additional cut representing the terrella A placed in a tub or vessel B floating on water.