CHAP. XI.

*

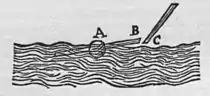

Wrought Iron, not excited by a loadstone,

draws iron.

The page and line references given in these notes are in all cases first to the Latin edition of 1600, and secondly to the English edition of 1900.

85 ^ Page 29, line 15. Page 29, line 16. Nos verò diligentiùs omnia experientes.—The method of carefully trying everything, instead of accepting statements on authority, is characteristic of Gilbert's work. The large asterisks affixed to Chapters IX. X. XI. XII. and XIII. of Book I. indicate that Gilbert considered them to announce important original magnetical discoveries. The electrical discoveries of Book II., Chapter II., are similarly distinguished. A rich crop of new magnetical experiments, marked with marginal asterisks, large and small, is to be found in Book II., from Chapter XV. to Chapter XXXIV.; while a third series of experimental magnetical discoveries extends throughout Book III.