1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63

Sextus[1] Julius Frontinus

Two Books on

The Aqueducts of Rome

Inasmuch as every task assigned by the Emperor demands especial attention; and inasmuch as I am incited, not merely to diligence, but also to devotion, when any matter is entrusted to me, be it as a consequence of my natural sense of responsibility or of my fidelity; and inasmuch as Nerva Augustus (an emperor of whom I am at a loss to say whether he devotes more industry or love to the State) has laid upon me the duties of water commissioner, an office which concerns not merely the convenience but also the health and even the safety of the City, and which has always been administered by the most eminent men of our State; now therefore I deem it of the first and greatest importance to familiarize myself with the business I have undertaken, a policy which I have always made a principle in other affairs.

For I believe that there is no surer foundation for any business than this, and that it would be otherwise impossible to determine what ought to be done, what ought to be avoided; likewise that there is nothing so disgraceful for a decent man as to conduct an office delegated to him, according to the instructions of assistants. Yet precise]y this is inevitable whenever a person inexperienced in the matter in hand has to have recourse to the practical knowledge of subordinates. For though the latter play a necessary role in the way of rendering assistance, yet they are, as it were, but the hands and tools of the directing head. Observing, therefore, the practice which I have followed in many offices, I have gathered in this sketch (into one systematic body, so to speak) such facts, hitherto scattered, as I have been able to get together, which bear on the general subject, and which might serve to guide me in my administration. Now in the case of other books which I have written after practical experience, I consulted the interests of my successors. The present treatise also may be found useful by my successor, but it will serve especially for my own instruction and guidance, being prepared, as it is, at the beginning of my administration.

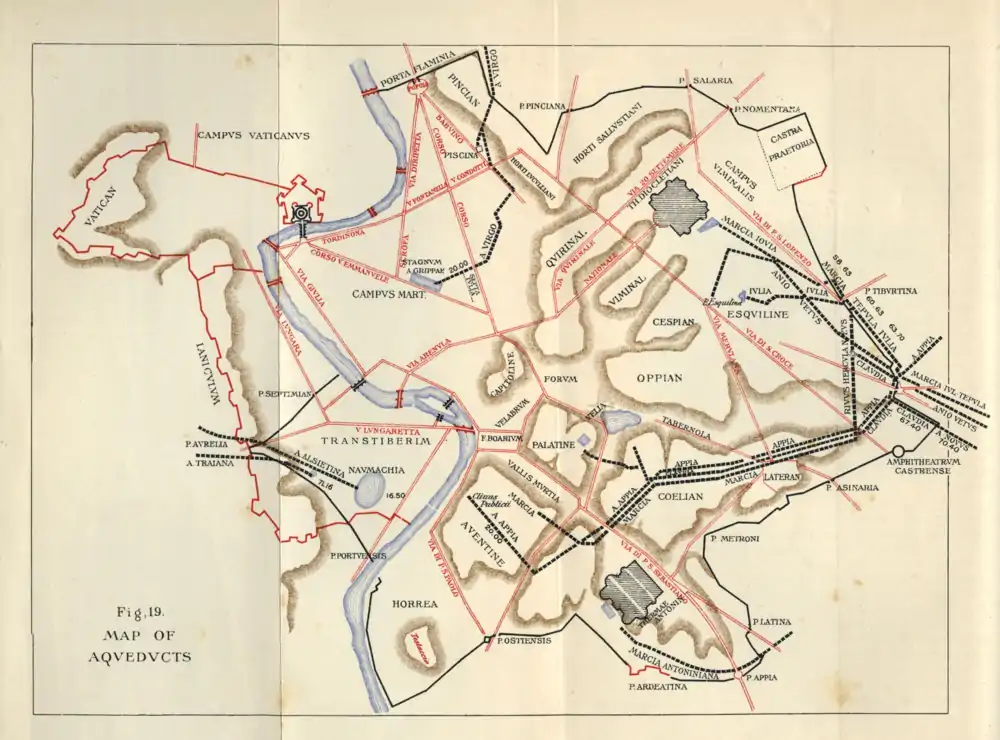

And lest I seem to have omitted anything requisite to a familiarity with the entire subject, I will first set down the names of the waters which enter the City of Rome; then I will tell by whom, under what consuls, and in what year after the founding of the City each one was brought in; then at what point and at what milestone each water was taken; how far each is carried in a subterranean channel, how far on substructures,[2] how far on arches. Then I will give the elevation[3] of each, [the plan] of the taps, and the distributions that are made from them; how much each aqueduct brings to points outside the City, what proportion to each quarter within the City; how many public reservoirs there are, and from these how much is delivered to public works, how much to ornamental fountains[4] (munera, as the more polite call them), how much to the water-basins; how much is granted in the name of Caesar; how much for private uses by favour of the Emperor; what is the law with regard to the construction and maintenance of the aqueducts, what penalties enforce it, whether established by resolutions of the Senate or by edicts of the Emperors.

Book I

For four hundred and forty-one years from the foundation of the City, the Romans were satisfied with the use of such waters as they drew from the Tiber, from wells, or from springs. Esteem for springs still continues, and is observed with veneration. They are believed to bring healing to the sick, as, for example, the springs of the Camenae,[5] of Apollo,[5] and of Juturna.[6] But there now run into the City: the Appian aqueduct, Old Anio, Marcia, Tepula, Julia, Virgo, Alsietina, which is also called Augusta, Claudia, New Anio.

In the consulship of Marcus Valerius Maximus and Publius Decius Mus,[7] in the thirtieth year after the beginning of the Samnite War, the Appian aqueduct was brought into the City by Appius Claudius Crassus, the Censor, who afterwards received the surname of "the Blind," the same man who had charge of paving the Appian Way from the Porta Capena[8] as far as the City of Capua. As colleague in the censorship Appius had Gaius Plautius, to whom was given the name of "the Hunter"[9] for having discovered the springs of this water. But since Plautius resigned the censorship within a year and six months,[10] under the mistaken impression that

- ↑ Praenomen not in C but attested by CIL. vi. 2222, viii. 7066, ix. 6083. 78.

- ↑ When it was necessary to carry the water pipes at a high elevation, the arched support was used in order to save masonry; otherwise a low foundation was built, to which the term substructio is applied.

- ↑ i.e. at the point of its entrance into the City.

- ↑ The conventional interpretation of a very uncertain word.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 The location of these is uncertain.

- ↑ This fountain is close to the Temple of Castor and Pollux, on the south side of the Roman Forum.

- ↑ 312 B.C.

- ↑ This gate was on the south side of the City, in the old Servian Wall.

- ↑ The English rendering does not reproduce the word play in venas Venocis.

- ↑ Eighteen months was the regular term of office for the censors.

Reproduced by permission of the Houghton Mifflin Company, from Lanciani's "Ruins and Excavations of Ancient Rome"

his colleague would do the same, the honour of giving his name to the aqueduct fell to Appius alone, who, by various subterfuges, is reported to have extended the term of his censorship, until he should complete both the Way and this aqueduct. The intake of Appia is on the Lucullan estate, between the seventh and eighth milestones, on the Praenestine Way, on a cross-road, 780 paces[1] to the left.[2] From its intake to the Salinae at the Porta Trigemina,[3] its channel has a length of 11,190 paces, of which 11,130 paces run underground, while above ground sixty paces are carried on substructures and, near the Porta Capena, on arches. Near Spes Vetus,[4] on the edge of the Torquatian and Epaphroditian Gardens, there joins it a branch of Augusta, added by Augustus as a supplementary supply… This branch has its intake at the sixth milestone, on the Praenestine Way, on a cross-road, 980 paces to the left, near the Collatian Way. Its course, by underground channel, extends to 6,380 paces before reaching The Twins.[5] The distribution of Appia begins at the foot of the Publician Ascent, near the Porta Trigemina, at the place designated as the Salinae.[6]

Forty years after Appia was brought in, in the four hundred and eighty-first year[7] from the founding of the City, Manius Curius Dentatus, who held the censorship with Lucius Papirius Cursor, contracted to have the waters of what is now called Old[8] Anio brought into the City, with the proceeds of the booty captured from Pyrrhus. This was in the second consulship of Spurius Carvilius and Lucius Papirius. Then two years later the question of completing the aqueduct was discussed in the Senate on the motion…of the praetor. At the close of the discussion, Curius, who had let the original contract, and Fulvius Flaccus were appointed by decree of the Senate as a board of two to bring in the water Within five days of the time he had been appointed, one of the two commissioners, Curius, died; thus the credit of achieving the work rested with Flaccus. The intake of Old Anio is above Tibur[9] at the twentieth milestone outside the…Gate, where it gives a part of its water to supply the Tiburtines. Owing to the exigence of elevation,[10] its conduit has a length of 43,000 paces. Of this, the channel runs underground for 42,779 paces, while there are above ground substructures for 221 paces.

One hundred and twentv-seven years later, that is in the six hundred and eighth year from the founding of the City,[11] in the consulship of Servius Sulpicius Galba and Lucius Aurelius Cotta, when the conduits of Appia and Old Anio had become leaky by reason of age, and water was also being diverted from them unlawfully by individuals, the Senate commissioned Marcius, who at that time administered the law as praetor between citizens,[12] to reclaim and repair these conduits; and since the growth of the City was seen to demand a more bountiful supply of water, the same man was charged by the Senate to bring into the City other waters so far as he could.… He restored the old channels and brought in a third supply, more wholesome than these,…which is called Marcia after the man who introduced it. We read in Fenestella,[13] that 180,000,000 sesterces[14] were granted to Marcius for these works, and since the term of his praetorship was not sufficient for the completion of the enterprise, it was extended for a second year. At that time the Decemvirs,[15] on consulting the Sibylline Books for another purpose, are said to have discovered that it was not right for the Marcian water, or rather the Anio (for tradition more regularly mentions this) to be brought to the Capitol. The matter is said to have been debated in the Senate, in the consulship of Appius Claudius and Quintus Caecilius,[16] Marcius Lepidus acting as spokesman for the Board of Decemvirs; and three years later the matter is said to have been brought up again by Lucius Lentulus, in the consulship of Gaius Laelius and Quintus Servilius,[17] but on both occasions the influence of Marcius Rex carried the day; and thus the water was brought to the Capitol. The intake of Marcia is at the thirty-sixth milestone on the Valerian Way, on a cross-road, three miles to the right as you come from Rome. But on the Sublacensian Way, which was first paved under the Emperor Nero, at the thirty-eighth milestone, within 200 paces to the left [a view of its source may be seen]. Its waters stand like a tranquil pool, of deep green hue. Its conduit has a length, from the intake to the City, of 61,710½ paces; 54,247½ paces of underground conduit; 7,463 paces on structures above ground, of which, at some distance from the City, in several places where it crosses valleys, there are 463 paces on arches; nearer the City, beginning at the seventh milestone, 528 paces on substructures, and the remaining 6,472 paces on arches.

The Censors, Gnaeus Servilius Caepio and Lucius Cassius Longinus, called Ravilla, in the year 627[18] after the founding of the City, in the consulate of Marcius Plautius Hvpsaeus and Marcus Fulvius Flaccus,[19] had the water called Tepula brought to Rome and to the Capitol, from the estate of Lucullus, which some persons hold to belong to Tusculan[20] territory. The intake of Tepula is at the tenth milestone on the Latin Way, near a cross-road, two miles to the right as you proceed from Rome.… From that point it was conducted in its own[21] channel to the City.

Later…in the second consulate[22] of the Emperor Caesar Augustus, when Lucius Volcatius was his colleague, in the year 719[23] after the foundation of the City, [Marcus] Agrippa, when aedile, after his first consulship,[24] took another independent source of supply, at the twelfth milestone from the City on the Latin Way, on a cross-road two miles to the right as you proceed from Rome, and also tapped Tepula. The name Julia was given to the new aqueduct by its builder, but since the waters were again divided for distribution, the name Tepula remained.[25] The conduit of Julia has a length of 15,426½ paces; 7,000 paces on masonry above ground, of which 528 paces next the City, beginning at the seventh milestone, are on substructures, the other 6,472 paces being on arches. Past the intake of Julia flows a brook, which is called Crabra. Agrippa refrained from taking in this brook either because he had condemned it, or because he thought it ought to be left to the proprietors at Tusculum, for this is the water which all the estates of that district receive in turn, dealt out to them on regular days and in regular quantities. But our water-men,[26] failing to practise the same restraint, have always claimed a part of it to supplement Julia, not, however, thus increasing the actual flow of Julia, since they habitually exhausted it by diverting its waters for their own profit. I therefore shut off the Crabra brook and at the Emperor's command restored it entirely to the Tusculan proprietors, who now, possibly not without surprise, take its waters, without knowing to what cause to ascribe the unusual abundance. The Julian aqueduct, on the others hand, by reason of the destruction of the branch pipes through which it was secretly plundered, has maintained its normal quantity even in times of most extraordinary drought. In the same year, Agrippa repaired the conduits of Appia, Old Anio, and Marcia, which had almost worn out, and with unique forethought provided the City with a large number of fountains.

The same man, after his own third consulship, in the consulship of Gaius Sentius and Quintus Lucretius,[27] twelve years after he had constructed the Julian aqueduct, also brought Virgo to Rome, taking it from the estate of Lucullus. We learn that June 9 was the day that it first began to flow in the City. It was called Virgo, because a young girl pointed out certain springs to some soldiers hunting for water, and when they followed these up and dug, they found a copious supply. A small temple, situated near the spring, contains a painting which illustrates this origin of the aqueduct. The intake of Virgo is on the Collatian Way at the eighth milestone, in a marshy spot, surrounded by a concrete enclosure for the purpose of confining the gushing waters. Its volume is augmented by several tributaries. Its length is 14,105 paces. For 12,865 paces of this distance it is carried in an underground channel, for 1,240 paces above ground. Of these 1,240 paces, it is carried for 540 paces on substructures at various points, and for 700 paces on arches. The underground conduits of the tributaries measure 1,405 paces.

I fail to see what motive induced Augustus, a most sagacious sovereign, to bring in the Alsietinian water, also called Augusta. For this has nothing to commend it,—is in fact positively unwholesome, and for that reason is nowhere delivered for consumption by the people. It may have been that when Augustus began the construction of his Naumachia,[28] he brought this water in a special conduit, in order not to encroach on the existing supply of wholesome water, and then granted the surplus of the Naumachia to the adjacent gardens and to private users for irrigation. It is customary, however, in the district across the Tiber, in an emergency, whenever the bridges[29] are undergoing repairs and the water supply is cut off from this side the river, to draw from Alsietina to maintain the flow of the public fountains. Its source is the Alsietinian Lake, at the fourteenth milestone, on the Claudian Way, on a cross-road, six miles and a half to the right. Its conduit has a length of 22,172 paces, with 358 paces on arches.

To supplement Marcia, whenever dry seasons required an additional supply, Augustus also, by an underground channel, brought to the conduit of Marcia another water of the same excellent quality, called Augusta from the name of its donor. Its source is beyond the springs of Marcia; its conduit, up to its junction with Marcia, measures 800 paces.

After these aqueducts, Gaius Caesar,[30] the successor of Tiberius, in the second year of his reign, in the

- ↑ The conventional rendering of passus by "pace" is here followed, although the term applied in strictness to the distance between the outstretched hands, i.e. five Roman feet, equivalent to 4 feet 10⅓ inches of our measure.

- ↑ i.e. going from Rome.

- ↑ This was at the northern base of the Aventine Hill, near the Tiber.

- ↑ The Temple of Spes Vetus was just inside the Aurelian Wall, in the eastern quarter of the City, not far from the Porta Labicana (the modern Porta Maggiore). See plan facing p. 363.

- ↑ The name is evidently derived from the junction of the two aqueducts. "There are considerable remains of two large reservoirs in a garden just outside of the boundary-wall of the Sessorium. These two great reservoirs, so close together in the line of the Aqua Appia, seem to have been the Gemelli mentioned by Frontinus."—Parker.

- ↑ See map facing p. 341.

- ↑ 273 B.C.

- ↑ Cf. 13.

- ↑ The modern Tivoli, about eighteen miles to the east of Rome. See map at end of book.

- ↑ All ancient aqueducts are constructed on the principle of flow, not of pressure. The fall was necessarily very gradual. Consequently, when the intake was at a considerable elevation, long detours became necessary in bringing the water to the City.

- ↑ 146 B. C., but Galba and Cotta were consuls in 144 B. C.

- ↑ Praetor urbanus.

- ↑ A Roman historian; he died in 21 A.D.

- ↑ About £1,500,000. The sesterce at this period was worth about two pence.

- ↑ A board of ten men who had charge of the Sibylline Books.

- ↑ 143 B. C.

- ↑ 140 B.C.

- ↑ 127 B.C.

- ↑ 125 B.C.

- ↑ The country around Tusculum (the modern Frascati), a town in Latium about twenty miles south-east of Rome.

- ↑ Later it flowed in the same channel with Julia. Cf. note on 9.

- ↑ 33 B.C.

- ↑ 35 B.C.

- ↑ Cf. note 4 on ch. 98.

- ↑ Apparently the name Julia et Tepula was applied to it. "The Julia was admitted into the channel of the Tepula at the tenth milestone. At the sixth milestone the compound water was again divided into two conduits, proportioned to the volume of the springs."—Lanciani.

- ↑ The water-men are the men who receive the water from the State and in turn furnish it to the consumers.

- ↑ Agrippa was consul for the third time in 27 B.C. Gaius Sentius Saturninus and Quintus Lucretius were consuls in 19 B. C.

- ↑ Nauniachia was the name given to the artificial lakes prepared for exhibitions of sham naval battles; the same name was applied to the contests themselves. See map facing p. 341.

- ↑ Bridges sometimes served as carriers for the water pipes. Among the bridges crossing the Anio, Ponte Lupo near Gallicano served as transit for four waters, Marcia, Anio Vetus, Anio Novus and Claudia, besides a carriage-way and a bridle-path. At Lyons there are the ruins of a Roman bridge, which still contains lead pipes.

- ↑ Caligula, who reigned from 37 to 41 A.D.

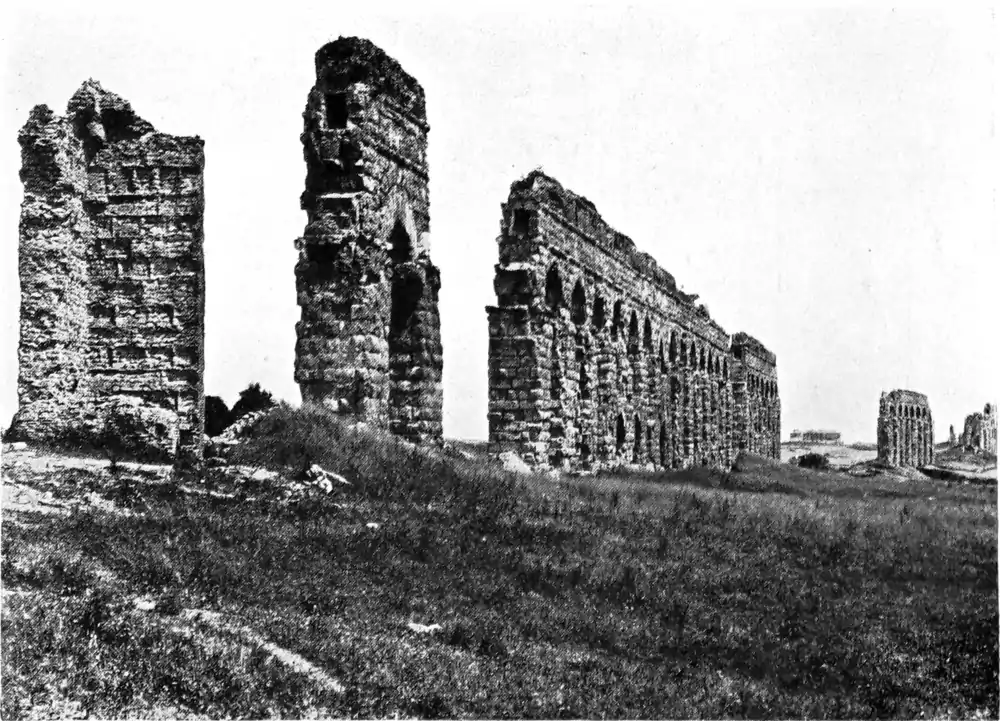

Ruins of Aqua Claudia

consulate of Marcus Aquila Julianus and Publius Nonius Asprenas, in the year 791[1] after the founding of the City, began two others, inasmuch as the seven then existing seemed insufficient to meet both the public needs and the luxurious private demands of the day. These works Claudius completed on the most magnificent scale,[2] and dedicated in the consulship of Sulla and Titianus,[3] on the 1st of August in the year 803[4] after the founding of the City. To the one water, which had its sources in the Caerulean and Curtain springs, was given the name Claudia. This is next to Marcia in excellence. The second began to be designated as New Anio, in order the more readily to distinguish by title the two Anios that had now begun to flow to the City. To the former Anio the name of "Old" was added.

The intake of Claudia is at the thirty-eighth milestone on the Sublacensian ^^ ay, on a cross-road, less than three hundred paces to the left. The water comes from two very large and beautiful springs, the Caerulean,[5] so designated from its appearance, and the Curtian. Claudia also receives the spring which is called Albudinus, which is of such excellence that, when Marcia, too, needs supplementing, this water answers the purpose so admirably that by its addition there is no change in Marcia's quality the spring of Augusta was turned into Claudia, because it was plainly evident that Marcia was of sufficient volume by itself. But Augusta remained, nevertheless, a reserve supply to Marcia, the understanding being that Augusta should run into Claudia only when the conduit of Marcia would not carry it. Claudia's conduit has a length of 46,406 paces, of

which 36,230 are in a subterranean channel, 10,176 on structures above ground; of these last there are at various points in the upper reaches 3,076 paces on arches; and near the City, beginning at the seventh milestone, 609 paces on substructures and 6,491 on arches.

The intake of New Anio is at the forty-second milestone on the Sublacensian Way, in the district of Simbruvium.[6] The water is taken from the river, which, even without the effect of rainstorms, is muddy and discoloured, because it has rich and cultivated fields adjoining it, and in consequence loose banks. For this reason, a settling reservoir was put in beyond the inlet of the aqueduct, in order that the water might settle there and clarify itself, between the river and the conduit. But even despite this precaution, the water reaches the City in a discoloured condition whenever there are rains. It is joined by the Herculanean Brook, which has its source on the same Way, at the thirty-eighth milestone, opposite the springs of Claudia, beyond the river and the highway. This is naturally very clear, but loses the charm of its purity by admixture with New Anio. The conduit of New Anio measures 58,700 paces, of which 49,300 are in an underground channel, 9,400 paces above ground on masonry; of these, at various points in the upper reaches are 2,300 paces on substructures or arches; while nearer the city, beginning at the seventh milestone, are 609 paces on substructures, 6,491 paces on arches. These are the highest arches, rising at certain points to 109 feet.

With such an array of indispensable structures carrying so many waters, compare, if you will, the idle Pyramids or the useless, though famous, works of the Greeks!

It has seemed to me not inappropriate to include also a statement of the lengths of the channels of the several aqueducts, according to the kinds of construction.[7] For since the chief function of this office of water-commissioner lies in their upkeep, the man in charge of them ought to know which of them demand the heavier outlay. My zeal was not satisfied with submitting details to examination: I also had plans made of the aqueducts, on which it is shown where there are valleys and how great these are; where rivers are crossed; and where conduits laid on hillsides demand more particular constant care for their maintenance and repair. By this provision, one reaps the advantage of being able to have the works before one's eyes, so to speak, at a moment's notice, and to consider them as though standing by their side.

The several aqueducts reach the City at different elevations. In consequence certain ones deliver water on higher ground, while others cannot rise to the loftier points; for the hills have gradually grown higher with rubbish in consequence of frequent conflagrations. There are five whose head rises to every point in the City, but of these some are forced up with greater, others with lesser pressure. The highest is New Anio; next comes Claudia; the third place is taken by Julia; the fourth by Tepula; the last by Marcia, although at its intake this mounts even to the level of Claudia. But the ancients laid the lines of their aqueducts at a lower elevation, either because they had not yet nicely worked out the art of levelling, or because they purposely sunk

- ↑ 38 A.D.

- ↑ Cf. Suet. Claud. 20.

- ↑ 52 A.D.

- ↑ 50 A.D.

- ↑ "The Blue."

- ↑ The Simbruvian Hills were about thirty miles to the northeast of Rome.

- ↑ i. e., how much under ground; how much on arches, etc.

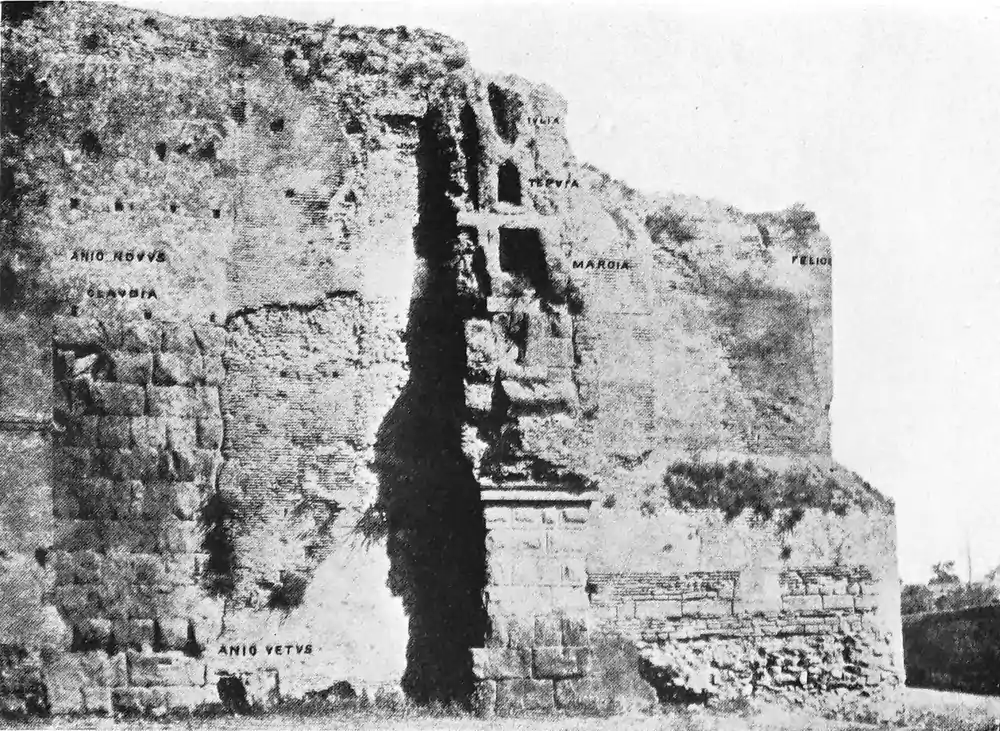

The seven aqueducts at the Porta Maggiore

their aqueducts in the ground, in order that they might not easily be cut by the enemy, since frequent wars were still waged with the Italians. But now, wherever a conduit has succumbed to old age, it is the practice to carry it in certain parts on substructures or on arches, in order to save length, abandoning the subterranean loops in the valleys.[1] The sixth rank in height is held by Old Anio, which would likewise be capable of supplying even the higher portions of the City, if it were raised up on substructures or arches, wherever the nature of the valleys and low places demands. Its elevation is followed by that of Virgo, then by that of Appia. These, since they were brought from points near the City, could not rise to such high elevations. Lowest of all is Alsietina, which supplies the ward across the Tiber and the very lowest districts.

Of these waters, six are received in covered catch-basins, this side the seventh milestone on the Latin Way. Here, taking fresh breath, so to speak, after the run, they deposit their sediment. Their volume also is determined by gauges set up at the same point.[2] Three of these, Julia, Marcia, and Tepula, are carried by the same arches from the catch-basins onward. Tepula, which, as we have above explained,[3] was tapped and added to the conduit of Julia, now leaves the basin of this same Julia, receives its own quota of water, and runs in its own conduit, under its own name. The topmost of these three is Julia; next below is Tepula; then Marcia.[4] These flowing [under ground] reach the level of the Viminal Hill, and in fact even of the Viminal Gate. There they again emerge. Yet a part of Julia is

- ↑ i.e., when old aqueducts were rebuilt, they were carried across valleys on arches or low foundations, instead of going around the valleys, as the original underground structures had done.

- ↑ Namely, in the basins.

- ↑ Cf. 9 and footnote.

- ↑ See illustration facing p. 361.

Fig. 2ᵃ [From Lanciani

first diverted at Spes Vetus, and distributed to the reservoirs of Mount Caelius. But Marcia delivers a part of its waters into the so-called Herculanean Brook, behind the Gardens of Pallas.[1] This brook, carried along the Caelian, affords no service to the occupants of the hill, on account of its low level; it ends beyond the Porta Capena.

New Anio and Claudia are carried together from their catch-basins on lofty arches, Anio being above.[2] Their arches end behind the Gardens of Pallas, and from that point their waters are distributed in pipes to serve the City. Yet Claudia first transfers a part of its waters near Spes Vetus to the so-called Neronian Arches. These arches pass along the Caelian Hill and end near the Temple of the Deified Claudius.[3] Both aqueducts deliver the volume which they receive, partly about the Caelian, partly on the Palatine and Aventine, and to the ward beyond the Tiber.

Old Anio, this side the fourth milestone, passes under New Anio, which here shifts from the Latin to the Labican Way; it has its own catch-basin. Then, this side the second milestone, it gives a part of its waters to the so-called Octavian Conduit and reaches the Asinian Gardens[4] in the neighbourhood of the New Way, whence it is distributed throughout that district. But the main conduit, which passes Spes Vetus, comes inside the Esquiline Gate and is distributed to high-lying mains throughout the city.

Neither Virgo, nor Appia, nor Alsietina has a receiving reservoir or catch-basin. The arches of Virgo begin under the Lucullan Gardens,[5] and end on the Campus Martins in front of the Voting Porticoes. The conduit of Appia, running along the base of the Caelian and Aventine, emerges, as we have said above,[6] at the foot of the Publician Ascent. The conduit of Alsietina terminates behind the Naumachia, for which it seems to have been constructed.

Since I have given in detail the builders of the several aqueducts, their dates, and, in addition, their sources, the lengths of their channels, and their elevations in sequence, it seems to me not out of keeping to add also some separate details, and to show how great is the supply which suffices not only for public and private uses and purposes, but also for the satisfaction of luxury; by how many reservoirs it is distributed and in what wards; how much water is delivered outside the City; how much in the City itself; how much of this latter amount is used for water-basins, how much for fountains, how much for public buildings, how much in the name of Caesar, how much for private consumption. But before I mention the names quinaria, centenaria, and those of the other ajutages[7] by which water is gauged, I deem it appropriate to state what is their origin, what their capacities, and what each name means; and, after setting forth the rule according to which their proportions and capacities are computed, to show in what way I discovered their discrepancies, and what course I pursued in correcting them.

The ajutages to measure water are arranged according to the standard either of digits or of inches.[8] Digits are the standard in Campania and in most parts of Italy; inches are the standard in…Now the digit, by common understanding, is 116 part of a foot;[9] the inch 112 part. But precisely as there is a difference between the inch and the digit, just so the standard of the digit itself is not uniform. One is called square; another, round. The square digit is larger than the round digit by 314 of its own size, while the round is smaller than the square by 311 of its size, obviously because the corners are cut off.[10]

Later on, an ajutage called a quinaria[11] came into use in the Citv, to the exclusion of the former measures. This was based neither on the inch, nor on either of the digits, but was introduced, as some think, by Agrippa, or, as others believe, by plumbers at the instance of Vitruvius, the architect. Those who represent Agrippa as its inventor, declare it was so designated because five small ajutages or punctures, so to speak, of the old sort, through which water used to be distributed when the supply was scanty, were now united in one pipe. Those who refer it to Vitruvius and the plumbers, declare that it was so named from the fact that a flat sheet of lead 5 digits wide, made up into a round pipe, forms this ajutage. But this is indefinite, because the plate, when made up into a round pipe, will be extended on the exterior surface and contracted on the interior surface. The most probable explanation is that the quinaria[12] received its name from having a diameter of 54 of a digit, a standard which holds in the following ajutages also up to the 20-pipe, the diameter of each pipe increasing by the addition of 14 of a digit. For example the 6-pipe is six quarters in diameter, a 7-pipe seven quarters, and so on by a uniform increase up to a 20-pipe.

Every ajutage, now, is gauged either by its diameter or circumference, or by its area of clear cross-section, from any of which factors its capacity becomes evident. That we may distinguish the more readilv between the inch ajutage, the square digit, the circular digit, and the quinaria itself, use must be made of the value of the quinaria, the ajutage which is most accurately determined and best known. Now the inch ajutage, has a diameter of 113 digits.[13] Its capacity is [slightly] more than 113 quinariae, i.e. 112 twelfths of a quinaria plus 3288 plus 23 of 1288 more. The square digit, reduced to the circle is 1 digit plus 112 twelfths of a digit plus 172 in diameter; its capacity is 1012 of a quinaria. The circular digit is 1 digit in diameter; its capacity is 712 plus 12 twelfth plus 172 of a quinaria.[14]

Now the ajutages which are derived from the quinaria increase on two principles. One principle is that the quinaria itself is taken a given number of times, i.e. in one orifice the equivalent of several quinariae is included, in which case the size of the orifice increases according to the increase in the number of quinariae. This principle is regularly employed, whenever several quinariae are delivered by one pipe and received in a reservoir, from which consumers receive their individual supply,—this being done in order that the conduit may not be tapped too often.[15]

The second principle is followed, whenever the pipe does not increase according to some necessary multiple of quinariae, but according to the size of diameters, in conformity with which principle they enlarge their capacity and receive their names; as for example, when a quarter [of a digit] is added to the diameter of a quinaria, we get as a result the senaria,[16] but its capacity is not increased by a whole quinaria, for it contains a quinaria plus 512 plus 148. So on, by adding successive quarters of a digit to the diameter, as was said above, we get by gradual increases, a 7-pipe (septenaria), an 8-pipe (octonaria), and up to the 20-pipe (vicenaria).

After that[17] we have the method of gauging which is based on the number of square digits contained in the cross-section, that is, the orifice of each ajutage, from which number of square digits the pipes also get their names. Thus those which in cross-section, that is, in circular orifice, have 25 square digits, are called 25-pipes. Similarly we have the 30-pipe (tricenaria), and so on, by a regular increase of 5 square digits, up to the 120-pipe.

In the case of the 20-pipe, which is on the border line between the two methods of gauging,[18] the two methods almost coincide. For according to the reckoning to be used in the first-named set of ajutages, it is twenty quarter digits in diameter, inasmuch as its diameter is 5 digits; while according to the computation to be applied to the higher ajutages, it has an area of 20 square digits, less a fraction.[19]

The gauging of the entire series of ajutages from the 5-pipe (quinaria) up to the 120-pipe, is determined in the way I have explained, and in each class the principle adopted is adhered to for that class. It conforms also to the ajutages set down and verified in the records of our most puissant and patriotic emperor.[20] Whether, therefore, computation or authority is to be followed, on either ground the ajutages of the records are of greater weight. But the water-men, while they conform to the obvious reckoning in most ajutages, have made deviation in the case of four of them, namely: the 12-, 20-, 100-, and 120-pipe.

In case of the 12-pipe, the error is not great, nor is its use frequent. They have added 124 plus 148 to its diameter, and to its capacity 14 of a quinaria. A greater discrepancy is detected in case of the three remaining ajutages. These water-men diminish the 20-pipe in its diameter by 12 plus 124 of a digit, its capacity by 3 quinariae plus 14 plus 124; and common use is made of this ajutage for delivery. But in case of the 100-pipe and 120-pipe, through which they[21] regularly receive water, the pipes are not diminished but enlarged! For to the diameter of the 100-pipe they add 23 plus 124 of a digit, and to the capacity, 10 quinariae plus 12 plus 124. To the diameter of the 120-pipe they add 3 digits plus 712 plus 124 plus 148; to its capacity, 66 quinariae plus 16.

Thus by diminishing the size of the 20-pipe by which they constantly deliver, and enlarging the 100- and 120-pipes, by which they always receive, they steal in case of the 100-pipe 27 quinariae, and in case of the 120-pipe 86 quinariae.[22] While this is proved by computation, it is also obvious from the facts. For from the 20-pipe, which Caesar rates[23] at 16 quinariae, they do not deliver more than 13; and it is equally certain that from the 100-pipe and the 120-pipe, which they have expanded, they deliver only up to a limited amount, since Caesar, as his records show, has made delivery according to his grant,[24] when out of each 100-pipe he furnishes 8112 quinariae, and similarly out of a 120-pipe, 98.

In all there are 25 ajutages. They all conform to their computed and recorded capacities, barring these four which the water-men have altered. But everything embraced under the head of mensuration ought to be fixed, unchanged, and constant. For onlv so will any special computation accord with general principles. Just as a sextarius,[25] for example, has a regular ratio to a cyathus,[26] and similarly a modius[27] to both a cyathus and sextarius, so also the multiplication of the quinariae in case of the larger ajutages must follow a regular progression. However, when less is found in the delivery ajutages and more in the receiving ajutages, it is obvious that there is not error, but fraud.

Let us remember that every stream of water, whenever it comes from a higher point and flows into a reservoir after a short run, not only comes up to its measure, but actually yields a surplus; but whenever it comes from a lower point, that is, under less pressure, and is conducted a longer distance, it shrinks in volume, owing to the resistance of its conduit; and that, therefore, on this principle it needs either a check or a help in its discharge.[28]

But the position of the calix is also a factor. Placed at right angles and level, it maintains the normal quantity. Set against the current of the water, and sloping downward, it will take in more. If it slopes to one side, so that the water flows by, and if it is inclined with the current, that is, is less favourably placed for taking in water, it will receive the water slowly and in scant quantity. The calix, now, is a bronze ajutage, inserted into a conduit or reservoir, and to it the service pipes are attached. Its length ought not to be less than 12 digits, while its orifice ought to have such capacity as is specified.[29] Bronze seems to have been selected, since, being hard, it is more difficult to bend, and is not easily expanded or contracted.

I have described below all the 25 ajutages that there are (although only 15 of them are in use), gauging them according to the method of computation spoken of,[30] and correcting the four which the water-men have altered. To these specifications all ajutages in use ought to conform, or if those four remain in use, they ought to be gauged by the number of quinariae which they contain. The ajutages that are not in use are so referred to.

The inch ajutage[31] is 1 digit plus 13 of a digit in diameter; it contains more than a quinaria by 112 twelfths of a quinaria plus 3288 plus 23 of 1288. The square digit has the same height as breadth. The square digit converted into its equivalent circle is 1 digit plus 112 twelfths of a digit plus 172 in diameter; it measures 1012 of a quinaria. The circular digit is 1 digit in diameter; and measures 712 plus a 12 twelfth plus 172 of a quinaria in area.

The quinaria: 1 digit plus 312 in diameter; 3 digits plus 12 plus 512 plus 3288 circumference; it has a capacity of 1 quinaria.

The 6-pipe: 112 digits in diameter; 4 digits plus 12 plus 212 plus 124 plus 2288 in circumference; it has a capacity of 1 quinaria plus 512 plus 7288.

The 7-pipe: 1 digit plus 12 plus 312 in diameter: 5 digits plus 12 in circumference; it has a capacity of 1 quinaria, plus 12 plus 512 plus 124; is not in use.

The 8-pipe: 2 digits in diameter; 6 digits plus 312 plus 10288 in circumference; it has a capacity of 2 quinariae plus 12 plus 124 plus 5288.

The 10-pipe: 212 digits in diameter; 7 digits plus 12 plus 412 plus 7288 in circumference; it has a capacity of 4 quinariae.

The 12-pipe: 3 digits in diameter; 9 digits plus 15 12 plus 3288 in circumference; it has a capacity of 5 quinariae plus 12 plus 312 plus 3288; is not in use.

But with the water-men it measured 3 digits plus 124 plus 6288 in diameter, containing 6 quinariae.

The 15-pipe: 3 digits plus 12 plus 312 in diameter; 11 digits plus 12 plus 312 plus 10288 in circumference; it has a capacity of 9 quinariae.

The 20-pipe: 5 digits plus 124 plus 1288 in diameter; 15 digits plus 12 plus 412 plus 6288 in circumference; it has a capacity of 16 quinariae plus 312 plus 124. With the water-men it measured 4 digits plus 12 in diameter, holding 13 quinariae.

The 25-pipe: 5 digits plus 12 plus 112 plus 124 plus 5288 in diameter; 17 digits plus 12 plus 212 plus 124 plus 7288 in circumference; it has a capacity of 20 quinariae plus 412 plus 9288; is not in use.

The 30-pipe: 6 digits plus 212 plus 3288 in diameter; 19 digits plus 512 in circumference; it has a capacity of 24 quinariae plus 512 plus 5288.

The 35-pipe: 6 digits plus 12 plus 212 plus 2288 in diameter; 20 digits plus 12 plus 512 plus 124 plus 4288 in circumference; it has a capacity of 28 quinariae plus 12 plus 3288; is not in use.

The 40-pipe: 7 digits plus 112 plus 124 plus 3288 diameter; 22 digits plus 512 in circumference; it has a capacity of 32 quinariae plus 12 plus 112.

The 45-pipe: 7 digits plus 12 plus 124 plus 8288 in diameter; 23 digits plus 12 plus 312 plus 124 in circumference; it has a capacity of 36 quinariae plus 12 plus 112 plus 124 plus 8288; is not in use.

The 50-pipe: 7 digits plus 12 plus 512 plus 124 plus 5288 in diameter; 25 digits plus 124 plus 7288 in circumference; it has a capacity of 40 quinariae plus 12 plus 212 plus 124 plus 5288.

The 55-pipe: 8 digits plus 412 plus 10288 in diameter; 26 digits plus 312 plus 124 in circumference; it has a capacity of 44 quinariae plus 12 plus 312 plus 124 plus 2288; is not in use.

The 60-pipe: 8 digits plus 12 plus 212 plus 124 plus 8288 in diameter; 27 digits plus 512 plus 124 in circumference; it has a capacity of 48 quinariae plus 12 plus 412 plus 11288.

The 65-pipe: 9 digits plus 112 plus 3288 in diameter; 28 digits plus 12 plus 112 in circumference; it has a capacity of 52 quinariae plus 12 plus 312 plus 124 plus 3288; is not in use.

The 70 pipe: 9 digits plus 512 plus 6288 in diameter; 29 digits plus 12 plus 212 in circumference; it has a capacity of 57 quinariae plus 5288.

The 75-pipe: 9 digits plus 122 plus 312 plus 6288 in diameter; 30 digits plus 12 plus 212 plus 8288 in circumference; it has a capacity of 61 quinariae plus 112 plus 2288; is not in use.

The 80-pipe: 10 digits plus 12 plus 2288 in diameter; 31 digits plus 12 plus 212 plus 124 in circumference; it has a capacity of 65 quinariae plus 212.

The 85-pipe: 10 digits plus 412 plus 124 plus 7288 in diameter; 32 digits plus 12 plus 212 plus 4288 in circumference; it has a capacity of 69 quinariae plus 312; is not in use.

The 90-pipe: 10 digits plus 12 plus 212 plus 10288 in diameter; 33 digits plus 12 plus 112 plus 124 plus 2288 in circumference; it has a capacity of 73 quinariae plus 312 plus 124 plus 5288.

The 95-pipe: 10 digits plus 12 plus 512 plus 124 plus 9288 in diameter; 34 digits plus 12 plus 124 in circumference; it has a capacity of 77 quinariae plus 412 plus 124 plus 5288; is not in use.

The 100-pipe: 11 digits plus 312 plus 9288 in diameter; 35 digits plus 512 plus 124 in circumference; it has a capacity of 81 quinariae plus 512 plus 10288. With the water-men it had u diameter of 12 digits; having a capacity of 92 quinariae.

The 120-pipe: 12 digits plus 412 plus 6288 in diameter; 38 digits plus 12 plus 412 in circumference; it has a capacity of 97 quinariae plus 12 plus 312. With the water-men it had a diameter of 16 digits, having a capacity of 163 quinariae plus 12 plus 512, which is the measure of two 100-pipes.

- ↑ On the Esquiline.

- ↑ See illustration facing p. 355.

- ↑ Cf. 76, 87.

- ↑ South of the Caelian, near the Baths of Caracalla.

- ↑ On the Pincian.

- ↑ Cf. 5.

- ↑ The ajutage was the nozzle, fitted to the water-pipe. The size and character of the ajutage, therefore, were important factors in the measurement of the water discharged. The ajutage was gauged according to various principles. Cf. 26.

- ↑ One of the most serious abuses practised by the water-men at Rome was connected with the size of the pipes used in the receiving and the distribution of water. Cf. 112, 113, 114. Since the size and position (cf. 36) of the ajutage controlled the amount discharged, it was necessary to know the exact capacity of each type, and Frontinus, therefore, enumerates these first of all.

- ↑ The Roman foot measured 11∙6 English inches, 0∙296 m

- ↑ The difference between the areas of a square digit and a round digit whose diameter is equal to the side of the square digit is easily seen:

- ↑ The quinaria was a measure not of volume but of capacity, i.e. as much water as would flow through a pipe one and a quarter digits in diameter, constantly discharging under pressure. "A quinaria was about 5,000 or 6,000 United States gallons per twenty-four hours, plus or minus 2,000 or 3,000 gallons, according to circumstances, favourable or unfavourable" (Herschel).

- ↑ i.e. "a fiver."

- ↑ Cf. 38 ff.

- ↑ Frontinus's fractions and the symbols which represent them are as follows. The total value in each case is the sum of the various members.

Uncia 112 𐆑 or · Sextans 16 𐆐 or Z Quadrans 14 𐆐𐆑 or :· Triens 13 𐆐𐆐 or :: Quincunx 512 𐆐𐆐𐆑 Semissis 12 S Septunx 712 S𐆑 Bes 23 S𐆐 Dodrans 34 S𐆐𐆑 Dextans 1012 S𐆐𐆐 Deunx 1112 S𐆐𐆐𐆑 Semuncia 12 · 112 (124) S̲ or 𐆒 Scripulus 1288 ℈ He also uses Sescuncia, 112×112, (or18); Duella, 136; Sicilicus, 148; and Sextula, 172; and depends on combinations of these to express exact terms. Owing to corruptions in text, Frontinus's figures are often at variance with obvious facts.

- ↑ Frontinus merely means that, instead of tapping the main conduit for individual consumers, the Romans delivered a given number of quinariae to a reservoir, from which the water was delivered to the consumer.

- ↑ It seems advisable to restate, for clearness' sake, the two principles of increase referred to by Frontinus. In the first class we have pipes, whose capacity is some multiple of the quinaria. In the second class, we have an ascending series of pipes each of which increases beyond the next smaller by a diameter of 14 inch. In other words the first class is based on multiples of volume; the second on slight increases in diameters.

- ↑ i.e. for the pipes above the 20-pipe.

- ↑ i.e. those mentioned in 28 and 29.

- ↑ By successive additions of a quarter of a digit to the diameter of a quinaria, the diameter of the vicenaria becomes five digits or twenty quarter digits. The number of square digits in the cross section, therefore, would be (almost twenty) square digits.

- ↑ Trajan is meant.

- ↑ The water-men.

- ↑ Frontinus's reckoning is as follows: The capacity of a 20-pipe is 16724 quinariae (cf. 46); the capacity of the 100-pipe is 8165144 quinariae (cf. 62) ; the capacity of five 20-pipes, therefore, practically equals that of one 100-pipe. Now, if the gain resulting from selling by short measure as 3724 quinariae in one 20-pipe, it will have been 161124 quinariae in five 20-pipes (or one 100-pipe). In the same way, since the capacity of the 120-pipe is 9734 quinariae (cf. 63), it is equal to six 20-pipes, and the gain in this case will have been 1934 quinariae. But by the increase of the pipes through which they receive water (cf. 32). the gain was 191324 quinariae in the case of the 100-pipe, and 6616 quinariae in case of the 120-pipe; so that by adding the gains made at both ends of the bargain, we arrive at an aggregate gain of 27 quinariae in case of the 100-pipe, and of 851112, practically 86, quinariae in case of the 120-pipe.

- ↑ Cf. 31.

- ↑ Literally: "stops distributing, as though the ajutage had run dry." Whoever wished to draw water for private uses had to seek for a grant and bring to the water-commissioner a writing from the sovereign (cf. 103, 105). Now, the records show that Caesar's grants from a 100-pipe amounted only to 81 quinariae, and from a 120-pipe to only 98 quinariae, leaving a surplus to be accounted for.

- ↑ The Roman pint.

- ↑ About a gill.

- ↑ The Roman peck.

- ↑ i.e. to make the pipe discharge the normal quantity allotted to a pipe of that size.

- ↑ i.e. in any particular instance.

- ↑ Cf. 26 ff.

- ↑ Cf. 26.