CHAPTER XV

THE SANDWICH ISLANDS

- Position and Physical Features—Zoology of the Sandwich Islands—Birds—Reptiles—Land-shells—Insects—Vegetation of the Sandwich Islands—Peculiar Features of the Hawaiian Flora—Antiquity of the Hawaiian Fauna and Flora—Concluding Observations on the Fauna and Flora of the Sandwich Islands—General Remarks on Oceanic Islands.

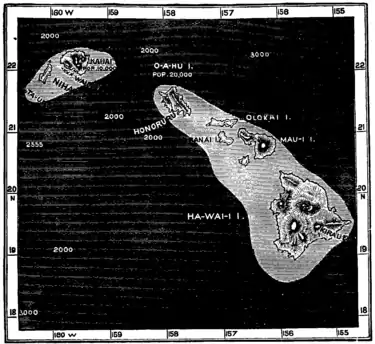

The Sandwich Islands are an extensive group of large islands situated in the centre of the North Pacific, being 2,350 miles from the nearest part of the American coast—the bay of San Francisco, and about the same distance from the Marquesas and the Samoa Islands to the south, and the Aleutian Islands a little west of north. They are, therefore, wonderfully isolated in mid-ocean, and are only connected with the other Pacific Islands by widely scattered coral reefs and atolls, the nearest of which, however, are six or seven hundred miles distant, and are all nearly destitute of animal or vegetable life. The group consists of seven large inhabited islands besides four rocky islets; the largest, Hawaii, being seventy miles across and having an area 3,800 square miles—being somewhat larger than all the other islands together. A better conception of this large island will be formed by comparing it with Devonshire, with which it closely agrees both in size and shape, though its enormous volcanic mountains rise to nearly 14,000 feet high. Three of the smaller islands are each about the size of Hertfordshire or Bedfordshire, and the whole group stretches from north-west to south-east for a distance of about 350 miles. Though so extensive, the entire archipelago is volcanic, and the largest island is rendered sterile and comparatively uninhabitable by its three active volcanoes and their widespread deposits of lava.

| The light tint shows where the sea is less than 1,000 fathoms deep. |

| The figures show the depth in fathoms. |

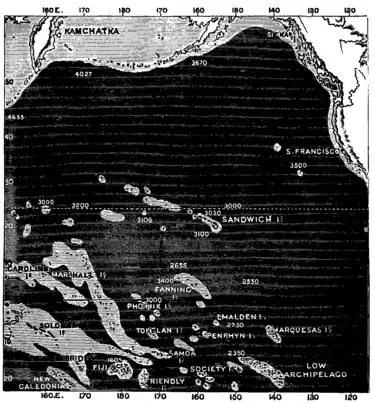

The ocean depths by which these islands are separated from the nearest continents are enormous. North, east, and south, soundings have been obtained a little over or under three thousand fathoms, and these profound deeps extend over a large part of the North Pacific. We may be quite sure, therefore, that the Sandwich Islands have, during their whole existence, been as completely severed from the great continents as they are now; but on the west and south there is a possibility of more extensive islands having existed, serving as stepping-stones to the island groups of the Mid-Pacific. This is indicated by a few widely-scattered coral islets, around which extend considerable areas of less depth, varying from two hundred to a thousand fathoms, and which may therefore indicate the sites of submerged islands of considerable extent. When we consider that east of New Zealand and New Caledonia, all the larger and loftier islands are of volcanic origin, with no trace of any ancient stratified rocks (except, perhaps, in the Marquesas, where, according to Jules Marcou, granite and gneiss are said to occur) it seems probable that the innumerable coral-reefs and atolls, which occur in groups on deeply submerged banks, mark the sites of bygone volcanic islands, similar to those which now exist, but which, after becoming extinct, have been lowered or destroyed by denudation, and finally have altogether disappeared except where their sites are indicated by the upward-growing coral-reefs. If this view is correct we should give up all idea of there ever having been a Pacific continent, but should look upon that vast ocean as having from the remotest geological epochs been the seat of volcanic forces, which from its profound depths have gradually built up the islands which now dot its surface, as well as many others which have sunk beneath its waves. The number of islands, as well as the total quantity of land-surface, may sometimes have been greater than it is now, and may thus have facilitated the transfer of organisms from one group to another, and more rarely even from the American, Asiatic, or Australian continents. Keeping these various facts and considerations in view, we may now proceed to examine the fauna and flora of the Sandwich Islands, and discuss the special phenomena they present.

| The light tint | shows | where | the sea is | less than 1,000 fathoms deep. |

| The dark tint | ,, | ,, | ,, | more than 1,000 fathoms deep. |

| The figures show the depths in fathoms. | ||||

Zoology of the Sandwich Islands: Birds.—It need hardly be said that indigenous mammalia are quite unknown in the Sandwich Islands, the most interesting of the higher animals being the birds, which are tolerably numerous and highly peculiar. Many aquatic and wading birds which range over the whole Pacific visit these islands, twenty-five species having been observed, but even of these six are peculiar—a coot, Fulica alai; a moorhen, Gallinula galeata var sandvichensis; a rail with rudimentary wings, Pennula millei; a stilt-plover, Himantopus knudseni; and two ducks, Anas Wyvilliana and Bernicla sandvichensis. The birds of prey are also great wanderers. Four have been found in the islands—the short-eared owl, Otus brachyotus, which ranges over the greater part of the globe, but is here said to resemble the variety found in Chile and the Galapagos; the barn owl, Strix flammea, of a variety common in the Pacific; a peculiar sparrow-hawk, Accipiter hawaii; and Buteo solitarius, a buzzard of a peculiar species, and coloured so as to resemble a hawk of the American subfamily Polyborinæ. It is to be noted that the genus Buteo abounds in America, but is not found in the Pacific; and this fact, combined with the remarkable colouration, renders it almost certain that this peculiar species is of American origin.

The Passeres, or true perching birds, are especially interesting, being all of peculiar species, and, all but one, belonging to peculiar genera. Their numbers have been greatly increased since the first edition of this work appeared, partly by the exertions of American naturalists, and very largely by the researches of Mr. Scott B. Wilson, who visited the Sandwich Islands for the purpose of investigating their ornithology, and collected assiduously in the various islands of the group for a year and a half. This gentleman is now publishing a finely illustrated work on Hawaiian birds, and he has kindly furnished me with the following list.

| Passeres of the Sandwich Islands. | ||

| Muscicapidæ (Flycatchers). | ||

| 1. | Chasiempis ridgwayi | Hawaii. |

| 2. | ,, sclateri | Kauai. |

| 3. | ,, dolei | Kauai. |

| 4. | ,, gayi | Oahu. |

| 5. | ,, ibidis | Oahu. |

| 6. | Phæornis obscura | Hawaii. |

| 7. | ,, myadestina | Kauai. |

| Meliphagidæ (Honeysuckers). | ||

| 8. | Acrulocercus nobilis | Hawaii. |

| 9. | ,, braccalus | Kauai. |

| 10. | ,, apicalis (extinct) | Oahu or Maui. |

| 11. | Chætoptila angustipluma (extinct) | Hawaii. |

|

Drepanididæ. | ||

| 12. | Drepanis pacifica (extinct) | Hawaii. |

| 13. | Vastiaria coccinea | All the Islands. |

| 14. | Hiniatione vireus | Hawaii. |

| 15. | ,, dolii | Maui. |

| 16. | ,, sanguinea | All the Islands. |

| 17. | ,, montana | Lanai. |

| 18. | ,, chloris | Oahu. |

| 19. | ,, maculata | Oahu. |

| 20. | ,, parva | Kauai. |

| 21. | ,, stejnegeri | Kauai. |

| 22. | Oreomyza bairdi | Kauai. |

| 23. | Hemignathus obscurus | Hawaii. |

| 24. | ,, olivaceus | Hawaii. |

| 25. | ,, lichtensteini | Oahu. |

| 26. | ,, lucidus | Oahu. |

| 27. | ,, stejnegeri | Kauai. |

| 28. | ,, hanapepe | Kauai. |

| 29. | Loxops coccinea | Hawaii. |

| 30. | ,, flammea | Molokai. |

| 31. | ,, aurea | Maui. |

| 32. | Chrysomitridops cœruleorostris | Kaui. |

| 33. | ,, anna (extinct) | |

| Fringillidæ (Finches). | ||

| 34. | Loxioides bailleni | Hawaii. |

| 35. | Psittirostra psittacea | All the Islands. |

| 36. | Chloridops kona | Hawaii. |

| Corvidæ (Crows). | ||

| 37. | Corvus hawaiiensis | Hawaii. |

Many of the birds recently described are representative forms found in the several islands of the group.

Taking the above in the order here given, we have, first, two peculiar genera of true flycatchers, a family confined to the Old World, but extending over the Pacific as far as the Marquesas Islands. Next we have two peculiar genera (with four species) of honeysuckers, a family confined to the Australian region, and also ranging over all the Pacific Islands to the Marquesas. We now come to the most important group of birds in the Sandwich Islands, comprising seven or eight peculiar genera, and twenty-two species which are believed to form a peculiar family allied to the Oriental flower-peckers (Diceidæ), and perhaps remotely to the American greenlets (Vireonidæ), or tanagers (Tanagridæ). They possess singularly varied beaks, some having this organ much thickened like those of finches, to which family some of them have been supposed to belong. In any case they form a most peculiar group, and cannot be associated with any other known birds. The last species, and the only one not belonging to a peculiar genus, is the Hawaiian crow, belonging to the almost universally distributed genus Corvus.

On the whole, the affinities of these birds are, as might be expected, chiefly with Australia and the Pacific Islands; but they exhibit in the buzzard, one of the owls, and perhaps in some of the Drepanididæ, slight indications of very rare or very remote communication with America. The amount of speciality is, however, wonderful, far exceeding that of any other islands; the only approach to it being made by New Zealand and Madagascar, which have a much more varied bird fauna and a smaller proportionate number of peculiar genera. The Galapagos, among the true oceanic islands, while presenting many peculiarities have only four out of the ten genera of Passeres peculiar. These facts undoubtedly indicate an immense antiquity for this group of islands, or the vicinity of some very ancient land (now submerged), from which some portion of their peculiar fauna might be derived. For further details as to the affinities and geographical distribution of the genera and species, the reader must consult Mr. Scott Wilson's work The Birds of the Sandwich Islands, already alluded to.

Reptiles.—The only other vertebrate animals are two lizards. One of these is a very widespread species, Ablepharus pœcilopleurus, ranging from the Pacific Islands to West Africa. The other is said to form a peculiar genus of geckoes, but both its locality and affinities appear to be somewhat doubtful.

Land-shells.—The only other group of animals which has been carefully studied, and which presents features of especial interest, are the land-shells. These are very numerous, about thirty genera, and between three and four hundred species having been described; and it is remarkable that this single group contains as many species of land-shells as all the other Polynesian Islands from the Pelew Islands and Samoa to the Marquesas. All the species are peculiar, and about three-fourths of the whole belong to peculiar genera, fourteen of which constitute the subfamily Achatinellinæ, entirely confined to this group of islands and constituting its most distinguishing feature. Thirteen genera (comprising sixty-four species) are found also in the other Polynesian Islands, but three genera of Auriculidæ (Plecotrema, Pedipes, and Blauneria) are not found in the Pacific, but inhabit—the former genus Australia, China, Bourbon, and Cuba, the two latter the West Indian Islands. Another remarkable peculiarity of these islands is the small number of Operculata, which are represented by only one genus and five species, while the other Pacific Islands have twenty genera and 115 species, or more than half the number of the Inoperculata. This difference is so remarkable that it is worth stating in a comparative form:—

| Inoperculata. | Operculata. | Auriculidæ. | |

| Sandwich Islands | 332 | 5 | 9 |

| Rest of Pacific Islands | 200 | 115 | 16 |

When we remember that in the West Indian Islands the Operculata abound in a greater proportion than even in the Pacific Islands generally, we are led to the conclusion that limestone, which is plentiful in both these areas, is especially favourable to them, while the purely volcanic rocks are especially unfavourable. The other peculiarities of the Sandwich Islands, however, such as the enormous preponderance of the strictly endemic Achatinellinæ, and the presence of genera which occur elsewhere only beyond the Pacific area in various parts of the great continents, undoubtedly point to a very remote origin, at a time when the distribution of many of the groups of mollusca was very different from that which now prevails.

A very interesting feature of the Sandwich group is the extent to which the species and even the genera are confined to separate islands. Thus the genera Carelia and Catinella with eight species are peculiar to the island of Kaui; Bulimella, Apex, Frickella, and Blauneria, to Oahu; Perdicella to Maui; and Eburnella to Lanai. The Rev. John T. Gulick, who has made a special study of the Achatinellinæ, informs us that the average range of the species in this sub-family is five or six miles, while some are restricted to but one or two square miles, and only very few have the range of a whole island. Each valley, and often each side of a valley, and sometimes even every ridge and peak possesses its peculiar species.[125] The island of Oahu, in which the capital is situated, has furnished about half the species already known. This is partly due to its being more forest-clad, but also, no doubt, in part to its being better explored, so that notwithstanding the exceptional riches of the group, we have no reason to suppose that there are not many more species to be found in the less explored islands. Mr. Gulick tells us that the forest region that covers one of the mountain ranges of Oahu is about forty miles in length, and five or six miles in width, yet this small territory furnishes about 175 species of Achatinellidæ, represented by 700 or 800 varieties. The most important peculiar genus, not belonging to the Achatinella group, is Carelia, with six species and several named varieties, all peculiar to Kaui, the most westerly of the large islands. This would seem to show that the small islets stretching westward, and situated on an extensive bank with less than a thousand fathoms of water over it, may indicate the position of a large submerged island whence some portion of the Sandwich Island fauna was derived.

Insects.—Owing to the researches of the Rev. T. Blackburn we have now a fair knowledge of the Coleopterous fauna of these islands. Unfortunately some of the most productive islands in plants—Kaui and Maui—were very little explored, but during a residence of six years the equally rich Oahu was well worked, and the general character of the beetle fauna must therefore be considered to be pretty accurately determined. Out of 428 species collected, many being obviously recent introductions, no less than 352 species and 99 of the genera appear to be quite peculiar to the archipelago. Sixty of these species are Carabidæ, forty-two are Staphylinidæ, forty are Nitidulidæ, twenty are Ptinidæ, twenty are Ciodidæ, thirty are Aglycyderidæ, forty-five are Curculionidæ, and fourteen are Cerambycidæ, the remainder being distributed among twenty-two other families. Many important families, such as Cicindelidæ, Scarabœidæ, Buprestidæ, and the whole of the enormous series of the Phytophaga are either entirely absent or are only represented by a few introduced species. In the eight families enumerated above most of the species belong to peculiar genera which usually contain numerous distinct species; and we may therefore consider these to represent the descendants of the most ancient immigrants into the islands.

Two important characteristics of the Coleopterous fauna are, the small size of the species, and the great scarcity of individuals. Dr. Sharp, who has described many of them,[126] says they are "mostly small or very minute insects," and that "there are few—probably it would be correct to say absolutely none—that would strike an ordinary observer as being beautiful." Mr. Blackburn says that it was not an uncommon thing for him to pass a morning on the mountains and to return home with perhaps two or three specimens, having seen literally nothing else except the few species that are generally abundant. He states that he "has frequently spent an hour sweeping flower-covered herbage, or beating branches of trees over an inverted white umbrella without seeing the sign of a beetle of any kind." To those who have collected in any tropical or even temperate country on or near a continent, this poverty of insect life must seem almost incredible; and it affords us a striking proof of how erroneous are those now almost obsolete views which imputed the abundance, variety, size, and colour of insects to the warmth and sunlight and luxuriant vegetation of the tropics. The facts become quite intelligible, however, if we consider that only minute insects of certain groups could ever reach the islands by natural means, and that these, already highly specialised for certain defined modes of life, could only develop slowly into slightly modified forms of the original types. Some of the groups, however, are considered by Dr. Sharp to be very ancient generalised forms, especially the peculiar family Aglycyderidæ, which he looks upon as being "absolutely the most primitive of all the known forms of Coleoptera, it being a synthetic form linking the isolated Rhynchophagous series of families with the Clavicorn series. About thirty species are known in the Hawaiian Islands, and they exhibit much difference inter se." A few remarks on each of the more important of the families will serve to indicate their probable mode and period of introduction into the islands.

The Carabidæ consist chiefly of seven peculiar genera of Anchomenini comprising fifty-one species, and several endemic species of Bembidiinæ. They are highly peculiar and are all of small size, and may have originally reached the islands in the crevices of the drift wood from N.W. America which is still thrown on their shores, or, more rarely, by means of a similar drift from the N.-Western islands of the Pacific.[127] It is interesting to note that peculiar species of the same groups of Carabidæ are found in the Azores, Canaries, and St. Helena, indicating that they possess some special facilities for transmission across wide oceans and for establishing themselves upon oceanic islands. The Staphylinidæ present many peculiar species of known genera. Being still more minute and usually more ubiquitous than the Carabidæ, there is no difficulty in accounting for their presence in the islands by the same means of dispersal. The Nitidulidæ, Ptinidæ, and Ciodidæ being very small and of varied habits, either the perfect insects, their eggs or larvæ, may have been introduced either by water or wind carriage, or through the agency of birds. The Curculionidæ, being wood bark or nut borers, would have considerable facilities for transmission by floating timber, fruits, or nuts; and the eggs or larvæ of the peculiar Cerambycidæ must have been introduced by the same means. The absence of so many important and cosmopolitan groups whose size or constitution render them incapable of being thus transmitted over the sea, as well as of many which seem equally well adapted as those which are found in the islands, indicate how rare have been the conditions for successful immigration; and this is still further emphasized by the extreme specialisation of the fauna, indicating that there has been no repeated immigration of the same species which would tend, as in the case of Bermuda, to preserve the originally introduced forms unchanged by the effects of repeated intercrossing.

Vegetation of the Sandwich Islands.—The flora of these islands is in many respects so peculiar and remarkable, and so well supplements the information derived from its interesting but scanty fauna, that a brief account of its more striking features will not be out of place; and we fortunately have a pretty full knowledge of it, owing to the researches of the German botanist Dr. W. Hildebrand.[128]

Considering their extreme isolation, their uniform volcanic soil, and the large proportion of the chief island which consists of barren lava-fields, the flora of the Sandwich Islands is extremely rich, consisting, so far as at present known, of 844 species of flowering plants and 155 ferns. This is considerably richer than the Azores (439 Phanerogams and 39 ferns), which though less extensive are perhaps better known, or than the Galapagos (332 Phanerogams), which are more strictly comparable, being equally volcanic, while their somewhat smaller area may perhaps be compensated by their proximity to the American continent. Even New Zealand with more than twenty times the area of the Sandwich group, whose soil and climate are much more varied and whose botany has been thoroughly explored, has not a very much larger number of flowering plants (935 species), while in ferns it is barely equal.

The following list gives the number of indigenous species in each natural order.

Number of Species in each Natural Order in the Hawaiian Flora, excluding the introduced Plants.

| Dicotyledons. | 48. | Gentianaceæ (Erythræa) | 1 | ||

| 1. | Ranunculaceæ | 2 | 49. | Loganiaceæ | 7 |

| 2. | Menispermaceæ | 4 | 50. | Apocynaceæ | 4 |

| 3. | Papaveraceæ | 1 | 51. | Hydrophyllaceæ (Nama ... | |

| 4. | Cruciferæ | 3 | allies Andes) | 1 | |

| 5. | Capparidaceæ | 2 | 52. | Oleaceæ | 1 |

| 6. | Violaceæ | 8 | 53. | Solanaceæ | 12 |

| 7. | Bixaceæ | 2 | 54. | Convolvulaceæ | 14 |

| 8. | Pittosporaceæ | 10 | 55. | Boraginaceæ | 3 |

| 9. | Caryophyllaceæ | 23 | 56. | Scrophulariaceæ | 2 |

| 10. | Portulaceæ | 3 | 57. | Gesneriaceæ | 24 |

| 11. | Guttiferæ | 1 | 58. | Myoporaceæ | 1 |

| 12. | Ternstræmiaceæ | 1 | 59. | Verbenaceæ | 1 |

| 13. | Malvaceæ | 14 | 60. | Labiatæ | 39 |

| 14. | Sterculiaceæ | 2 | 61. | Plantaginaceæ | 2 |

| 15. | Tiliaceæ | 1 | 62. | Nyctaginaceæ | 5 |

| 16. | Geraniaceæ | 6 | 63. | Amarantaceæ | 9 |

| 17. | Zygophyllaceæ | 1 | 64. | Phytolaccaceæ | 1 |

| 18. | Oxalidaceæ | 1 | 65. | Polygonaceæ | 3 |

| 19. | Rutaceæ | 30 | 66. | Chenopodiaceæ | 2 |

| 20. | Ilicineæ | 1 | 67. | Lauraceæ | 2 |

| 21. | Celastraceæ | 1 | 68. | Thymelæaceæ | 7 |

| 22. | Rhamnaceæ | 7 | 69. | Santalaceæ | 5 |

| 23. | Sapindaceæ | 6 | 70. | Loranthaceæ | 1 |

| 24. | Anacardiaceæ | 1 | 71. | Euphorbiaceæ | 12 |

| 25. | Leguminosæ | 21 | 72. | Urticaceæ | 15 |

| 26. | Rosaceæ | 6 | 73. | Piperaceæ | 20 |

| 27. | Saxifragaceæ (trees) | 2 | Monocotyledons. | ||

| 28. | Droseraceæ | 1 | |||

| 29. | Halorageæ | 1 | 74. | Orchidaceæ | 3 |

| 30. | Myrtaceæ | 6 | 75. | Scitaminaceæ | 4 |

| 31. | Lythraceæ | 1 | 76. | Iridaceæ | 1 |

| 32. | Onagraceæ | 1 | 77. | Taccaceæ | 1 |

| 33. | Cucurbitaceæ | 8 | 78. | Dioscoreaceæ | 2 |

| 34. | Ficoideæ | 1 | 79. | Liliaceæ | 7 |

| 35. | Begoniaceæ | 1 | 80. | Commelinaceæ | 1 |

| 36. | Umbelliferæ | 5 | 81. | Flagellariaceæ | 1 |

| 37. | Araliaceæ | 12 | 82. | Juncaceæ | 1 |

| 38. | Rubiaceæ | 49 | 83. | Palmaceæ | 3 |

| 39. | Compositæ | 70 | 84. | Pandanaceæ | 2 |

| 40. | Lobeliaceæ | 58 | 85. | Araceæ | 2 |

| 41. | Goodeniaceæ | 8 | 86. | Naiadaceæ | 4 |

| 42. | Vaccinaceæ | 2 | 87. | Cyperaceæ | 47 |

| 43. | Epacridaceæ | 2 | 88. | Graminaceæ | 57 |

| 44. | Sapotaceæ | 3 | Vascular Cryptogams. | ||

| 45. | Myrsinaceæ | 5 | |||

| 46. | Primulaceæ (Lysimachia) | Ferns | 136 | ||

| shrubs | 6 | Lycopodiaceæ | 17 | ||

| 47. | Plumbaginaceæ | 1 | Rhizocarpeæ | 2 | |

Peculiar Features of the Flora.—This rich insular flora is wonderfully peculiar, for if we deduct 115 species, which are believed to have been introduced by man, there remain 705 species of flowering plants of which 574, or more than four-fifths, are quite peculiar to the islands. There are no less than 38 peculiar genera out of a total of 265 and these 38 genera comprise 254 species, so that the most isolated forms are those which most abound and thus give a special character to the flora. Besides these peculiar types, several genera of wide range are here represented by highly peculiar species. Such are the Hawaiian species of Lobelia which are woody shrubs either creeping or six feet high, while a species of one of the peculiar genera of Lobeliaceæ is a tree reaching a height of forty feet. Shrubby geraniums grow twelve or fifteen feet high, and some vacciniums grow as epiphytes on the trunks of trees. Violets and plantains also form tall shrubby plants, and there are many strange arborescent compositæ, as in other oceanic islands.

The affinities of the flora generally are very wide. Although there are many Polynesian groups, yet Australian, New Zealand, and American forms are equally represented. Dr. Pickering notes the total absence of a large number of families found in Southern Polynesia, such as Dilleniceæa, Anonaceæ, Olacaceæ, Aurantiaceæ, Guttiferæ, Malpighiaceæ, Meliaceæ, Combretaceæ, Rhizophoraceæ, Melastomaceæ, Passifloraceæ, Cunoniaceæ, Jasminaceæ, Acanthaceæ, Myristicaceæ, and Casuaraceæ, as well as the genera Clerodendron, Ficus, and epidendric orchids. Australian affinities are shown by the genera Exocarpus, Cyathodes, Melicope, Pittosporum, and by a phyllodinous Acacia. New Zealand is represented by Ascarina, Coprosma, Acæna, and several Cyperaceæ; while America is represented by the genera Nama, Gunnera, Phyllostegia, Sisyrinchium, and by a red-flowered Rubus and a yellow-flowered Sanicula allied to Oregon species.

There is no true alpine flora on the higher summits, but several of the temperate forms extend to a great elevation. Thus Mr. Pickering records Vaccinium, Ranunculus, Silene, Gnaphalium and Geranium, as occurring above ten thousand feet elevation; while Viola, Drosera, Acæna, Lobelia, Edwardsia, Dodonæa, Lycopodium, and many Compositæ, range above six thousand feet. Vaccinium and Silene are very interesting, as they are almost peculiar to the North Temperate zone; while many plants allied to Antarctic species are found in the bogs of the high plateaux.

The proportionate abundance of the different families in this interesting flora is as follows:—

| 1. | Compositæ | 70 | species, | 12. | Urticaceæ | 15 | species, |

| 2. | Lobeliaceæ | 58 | ,, | 13. | Malvaceæ | 14 | ,, |

| 3. | Graminaceæ | 57 | ,, | 14. | Convolvulaceæ | 14 | ,, |

| 4. | Rubiaceæ | 49 | ,, | 15. | Araliaceæ | 12 | ,, |

| 5. | Cyperaceæ | 47 | ,, | 16. | Solanaceæ | 12 | ,, |

| 6. | Labiatæ | 39 | ,, | 17. | Euphorbiaceæ | 12 | ,, |

| 7. | Rutaceæ | 30 | ,, | 18. | Pittosporaceæ | 10 | ,, |

| 8. | Gesneriaceæ | 24 | ,, | 19. | Amarantaceæ | 9 | ,, |

| 9. | Caryophyllaceæ | 23 | ,, | 20. | Violaceæ | 8 | ,, |

| 10. | Leguminosæ | 21 | ,, | 21. | Goodeniaceæ | 8 | ,, |

| 11. | Piperaceæ | 20 | ,, |

Nine other orders, Geraniaceæ, Rhamnaceæ, Rosaceæ, Myrtaceæ, Primulaceæ, Loganiaceæ, Liliaceæ, Thymelaceæ, and Cucurbitaceæ, have six or seven species each; and among the more important orders which have less than five species each are Ranunculaceæ, Cruciferæ, Vaccinacæ, Apocynaceæ, Boraginaceæ, Scrophulariaceæ, Polygonaceæ, Orchidaceæ, and Juncaceæ. The most remarkable feature here is the great abundance of Lobeliaceæ, a character of the flora which is probably unique; while the superiority of Labiatæ to Leguminosæ and the scarcity of Rosaceæ and Orchidaceæ are also very unusual. Composites, as in most temperate floras, stand at the head of the list, and it will be interesting to note the affinities which they indicate. Omitting eleven species which are cosmopolitan, and have no doubt entered with civilised man, there remain nineteen genera and seventy species of Compositæ in the islands. Sixty-one of the species are peculiar, as are eight of the genera; while the genus Lipochæta with eleven species is only known elsewhere in the Galapagos, where a single species occurs. We may therefore consider that nine out of the nineteen genera of Hawaiian Compositæ are really confined to the Archipelago. The relations of the peculiar genera and species are indicated in the following table.[129]

Affinities of Hawaiian Composites.

| Peculiar Genera. | No. of Species. | External Affinities of the Genus. |

| Remya | 2 | Very peculiar. Allied to the North American genus Grindelia. |

| Tetramolobium | 7 | South Temperate America and Australia. |

| Lipochæta | 11 | Allied to American genera. |

| Campylothæca | 12 | With Tropical American species of Bidens and Coreopsis. |

| Argyroxiphium | 2 | With the Mexican Madieæ. |

| Wilkesia | 2 | Same affinities. |

| Dubantia | 6 | With the Mexican Raillardella. |

| Raillardia | 12 | Same affinities. |

| Hesperomannia | 2 | Allied to Stifftia and Wunderlichia of Brazil. |

| Peculiar Species. | ||

| Lagenophora | 1 | Australia, New Zealand, Antarctic America, Fiji Islands. |

| Senecio | 2 | Universally distributed. |

| Artemisia | 2 | North Temperate Regions. |

The great preponderance of American relations in the Compositæ, as above indicated, is very interesting and suggestive, since the Compositæ of Tahiti and the other Pacific Islands are allied to Malaysian types. It is here that we meet with some of the most isolated and remarkable forms, implying great antiquity; and when we consider the enormous extent and world-wide distribution of this order (comprising about ten thousand species), its distinctness from all others, the great specialisation of its flowers to attract insects, and of its seeds for dispersal by wind and other means, we can hardly doubt that its origin dates back to a very remote epoch. We may therefore look upon the Compositæ as representing the most ancient portion of the existing flora of the Sandwich Islands, carrying us back to a very remote period when the facilities for communication with America were greater than they are now. This may be indicated by the two deep submarine banks in the North Pacific, between the Sandwich Islands and San Francisco, which, from an ocean floor nearly 3,000 fathoms deep, rise up to within a few hundred fathoms of the surface, and seem to indicate the subsidence of two islands, each about as large as Hawaii. The plants of North Temperate affinity may be nearly as old, but these may have been derived from Northern Asia by way of Japan and the extensive line of shoals which run north-westward from the Sandwich Islands, as shown on our map. Those which exhibit Polynesian or Australian affinities, consisting for the most part of less highly modified species, usually of the same genera, may have had their origin at a later, though still somewhat remote period, when large islands, indicated by the extensive shoals to the south and south-west, offered facilities for the transmission of plants from the tropical portions of the Pacific Ocean.

It is in the smaller and most woody islands in the westerly portion of the group, especially in Kauai and Oahu, that the greatest number and variety of plants are found and the largest proportion of peculiar species and genera. These are believed to form the oldest portion of the group, the volcanic activity having ceased and allowed a luxuriant vegetation more completely to cover the islands, while in the larger and much newer islands of Hawaii and Maui the surface is more barren and the vegetation comparatively monotonous. Thus while twelve of the arborescent Lobeliaceæ have been found on Hawaii no less than seventeen occur on the much smaller Oahu, which has even a genus of these plants confined to it.

It is interesting to note that while the non-peculiar genera of flowering plants have little more than two species to a genus, the endemic genera average six and three-quarter species to a genus. These may be considered to represent the earliest immigrants which became firmly established in the comparatively unoccupied islands, and have gradually become modified into such complete harmony with their new conditions that they have developed into many diverging forms adapting them to different habitats. The following is a list of the peculiar genera with the number of species in each.

Peculiar Hawaiian Genera of Flowering Plants.

| Genus. | No. of Species. | Natural Order. | |

| 1. | Isodendrion | 3 | Violaceæ. |

| 2. | Schiedea (seeds rugose or muricate) | 17 | Caryophyllaceæ. |

| 3. | Alsinidendron | 1 | ,, |

| 4. | Pelea | 20 | Rutaceæ. |

| 5. | Platydesma | 4 | ,, |

| 6. | Mahoe | 1 | Sapindaceæ. |

| 7. | Broussaisia | 2 | Saxifragaceæ. |

| 8. | Hildebrandia | 1 | Begoniaceæ. |

| 9. | Cheirodendron (fleshy fruit) | 2 | Araliaceæ. |

| 10. | Pterotropia (succulent) | 3 | ,, |

| 11. | Triplasandra (drupe) | 4 | ,, |

| 12. | Kadua (small, flat, winged seeds) | 16 | Rubiaceæ. |

| 13. | Gouldia (berry) | 5 | ,, |

| 14. | Bobea (drupe) | 5 | ,, |

| 15. | Straussia (drupe) | 5 | ,, |

| 16. | Remya | 2 | Compositæ. |

| 17. | Tetramolobium | 7 | ,, |

| 18. | Lipochæta | 11 | ,, |

| 19. | Campylotheca | 12 | ,, |

| 20. | Argyroxiphium | 2 | ,, |

| 21. | Wilkesia | 2 | ,, |

| 22. | Dubautia | 6 | ,, |

| 23. | Raillardia | 12 | ,, |

| 24. | Hesperomannia | 2 | ,, |

| 25. | Brighamia | 1 | Lobeliaceæ. |

| 26. | Clermontia (berry) | 11 | ,, |

| 27. | Rollandia | 6 | ,, |

| 28. | Delissea | 7 | ,, |

| 29. | Cyanea | 28 | ,, |

| 30. | Labordea | 9 | Loganiaceæ. |

| 31. | Nothocestrum | 4 | Solanaceæ. |

| 32. | Haplostachys (nucules dry) | 3 | Labiatæ. |

| 33. | Phyllostegia (nucules fleshy) | 16 | ,, |

| 34. | Stenogyne (nucules fleshy) | 16 | ,, |

| 35. | Nototrichium | 3 | Amarantaceæ. |

| 36. | Charpentiera | 2 | ,, |

| 37. | Touchardia | 1 | Urticaceæ. |

| 38. | Neraudia | 2 | ,, |

| —— | |||

| Total | 254 | species. |

The great preponderance of the two orders Compositæ and Lobeliaceæ are what first strike us in this list. In the former case the facilities for wind-dispersal afforded by the structure of so many of the seeds render it comparatively easy to account for their having reached the islands at an early period. The Lobelias, judging from Hildebrand's descriptions, may have been transported in several different ways. Most of the endemic genera are berry-bearers and thus offer the means of dispersal by fruit-eating birds. The endemic species of the genus Lobelia have sometimes very minute seeds, which might be carried long distances by wind, while other species, especially Lobelia gaudichaudii, have a "hard, almost woody capsule which opens late," apparently well adapted for floating long distances. Afterwards "the calycine covering withers away, leaving a fenestrate woody network" enclosing the capsule, and the seeds themselves are "compressed, reniform, or orbicular, and margined," and thus of a form well adapted to be carried to great heights and distances by gales or hurricanes.

In the other orders which present several endemic genera indications of the mode of transit to the islands are afforded us. The Araliaceæ are said to have fleshy fruits or drupes more or less succulent. The Rubiaceæ have usually berries or drupes, while one genus, Kadua, has "small, flat, winged seeds." The two largest genera of the Labiatæ are said to have "fleshy nucules," which would no doubt be swallowed by birds.[130]

Antiquity of the Hawaiian Fauna and Flora.—The great antiquity implied by the peculiarities of the fauna and flora, no less than by the geographical conditions and surroundings, of this group, will enable us to account for another peculiarity of its flora—the absence of so many families found in other Pacific Islands. For the earliest immigrants would soon occupy much of the surface, and become specially modified in accordance with the conditions of the locality, and these would serve as a barrier against the intrusion of many forms which at a later period spread over Polynesia. The extreme remoteness of the islands, and the probability that they have always been more isolated than those of the Central Pacific, would also necessarily result in an imperfect and fragmentary representation of the flora of surrounding lands.

Concluding Observations on the Fauna and Flora of the Sandwich Islands.—The indications thus afforded by a study of the flora seem to accord well with what we know of the fauna of the islands. Plants having so much greater facilities for dispersal than animals, and also having greater specific longevity and greater powers of endurance under adverse conditions, exhibit in a considerable degree the influence of the primitive state of the islands and their surroundings; while members of the animal world, passing across the sea with greater difficulty and subject to extermination by a variety of adverse conditions, retain much more of the impress of a recent state of things, with perhaps here and there an indication of that ancient approach to America so clearly shown in the Compositæ and some other portions of the flora.

General Remarks on Oceanic Islands.

We have now reviewed the main features presented by the assemblages of organic forms which characterise the more important and best known of the Oceanic Islands. They all agree in the total absence of indigenous mammalia and amphibia, while their reptiles, when they possess any, do not exhibit indications of extreme isolation and antiquity. Their birds and insects present just that amount of specialisation and diversity from continental forms which may be well explained by the known means of dispersal acting through long periods; their land shells indicate greater isolation, owing to their admittedly less effective means of conveyance across the ocean; while their plants show most clearly the effects of those changes of conditions which we have reason to believe have occurred during the Tertiary epoch, and preserve to us in highly specialised and archaic forms some record of the primeval immigration by which the islands were originally clothed with vegetation. But in every case the series of forms of life in these islands is scanty and imperfect as compared with far less favourable continental areas, and no one of them presents such an assemblage of animals or plants as we always find in an island which we know has once formed part of a continent.

It is still more important to note that none of these oceanic archipelagoes present us with a single type which we may suppose to have been preserved from Mesozoic times; and this fact, taken in connection with the volcanic or coralline origin of all of them, powerfully enforces the conclusion at which we have arrived in the earlier portion of this volume, that during the whole period of geologic time as indicated by the fossiliferous rocks, our continents and oceans have, speaking broadly, been permanent features of our earth's surface. For had it been otherwise—had sea and land changed place repeatedly as was once supposed—had our deepest oceans been the seat of great continents while the site of our present continents was occupied by an oceanic abyss—is it possible to imagine that no fragments of such continents would remain in the present oceans, bringing down to us some of their ancient forms of life preserved with but little change? The correlative facts, that the islands of our great oceans are all volcanic (or coralline built probably upon degraded volcanic islands or extinct submarine volcanoes), and that their productions are all more or less clearly related to the existing inhabitants of the nearest continents, are hardly consistent with any other theory than the permanence of our oceanic and continental areas.

We may here refer to the one apparent exception, which, however, lends additional force to the argument. New Zealand is sometimes classed as an oceanic island, but it is not so really; and we shall discuss its peculiarities and probable origin further on.

125 ^ Journal of the Linnean Society, 1873, p. 496. "On Diversity of Evolution under one set of External Conditions." Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1873, p. 80. "On the Classification of the Achitinellidæ."

126 ^ "Memoirs on the Coleoptera of the Hawaiian Islands." By the Rev. T. Blackburn, B.A., and Dr. D. Sharp. Scientific Transactions of the Royal Dublin Society. Vol. III. Series II. 1885.

127 ^ See Hildebrand's Flora of the Hawaiian Islands, Introduction, p. xiv.

128 ^ Flora of the Hawaiian Islands, by W. Hildebrand, M.D., annotated and published after the author's death by W. F. Hildebrand, 1888.

129 ^ These are obtained from Hildebrand's Flora supplemented by Mr. Bentham's paper in the Journal of the Linnean Society.

130 ^ Among the curious features of the Hawaiian flora is the extraordinary development of what are usually herbaceous plants into shrubs or trees. Three species of Viola are shrubs from three to five feet high. A shrubby Silene is nearly as tall; and an allied endemic genus, Schiedea, has numerous shrubby species. Geranium arboreum is sometimes twelve feet high. The endemic Compositæ are mostly shrubs, while several are trees reaching twenty or thirty feet in height. The numerous Lobeliaceæ, all endemic, are mostly shrubs or trees, often resembling palms or yuccas in habit, and sometimes twenty-five or thirty feet high. The only native genus of Primulaceæ—Lysimachia—consists mainly of shrubs; and even a plantain has a woody stem sometimes six feet high.