CHAPTER XIV

ST. HELENA

- Position and Physical Features of St. Helena—Change Effected by European Occupation—The Insects of St. Helena—Coleoptera—Peculiarities and Origin of the Coleoptera of St. Helena—Land-shells of St. Helena—Absence of Fresh-water Organisms—Native Vegetation of St. Helena—The Relations of the St. Helena Compositæ—Concluding Remarks on St. Helena.

In order to illustrate as completely as possible the peculiar phenomena of oceanic islands, we will next examine the organic productions of St. Helena and of the Sandwich Islands, since these combine in a higher degree than any other spots upon the globe, extreme isolation from all more extensive lands, with a tolerably rich fauna and flora whose peculiarities are of surpassing interest. Both, too, have received considerable attention from naturalists; and though much still remains to be done in the latter group, our knowledge is sufficient to enable us to arrive at many interesting results.

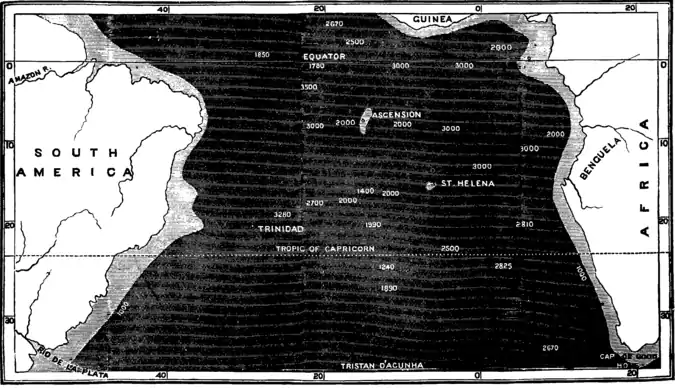

| The light tint shows depths of less than 1,000 fathoms. |

| The figures show depths of the sea in fathoms. |

Position and Physical Features of St. Helena.—This island is situated nearly in the middle of the South Atlantic Ocean, being more than 1,100 miles from the coast of Africa, and 1,800 from South America. It is about ten miles long by eight wide, and is wholly volcanic, consisting of ancient basalts, lavas, and other volcanic products. It is very mountainous and rugged, bounded for the most part by enormous precipices, and rising to a height of 2,700 feet above the sea-level. An ancient crater, about four miles across, is open on the south side, and its northern rim forms the highest and central ridge of the island. Many other hills and peaks, however, are more than two thousand feet high, and a considerable portion of the surface consists of a rugged plateau, having an elevation of about fifteen hundred to two thousand feet. Everything indicates that St. Helena is an isolated volcanic mass built up from the depths of the ocean. Mr. Wollaston remarks: "There are the strongest reasons for believing that the area of St. Helena was never very much larger than it is at present—the comparatively shallow sea-soundings within about a mile and a half from the shore revealing an abruptly defined ledge, beyond which no bottom is reached at a depth of 250 fathoms; so that the original basaltic mass, which was gradually piled up by means of successive eruptions from beneath the ocean, would appear to have its limit definitely marked out by this suddenly-terminating submarine cliff—the space between it and the existing coast-line being reasonably referred to that slow process of disintegration by which the island has been reduced, through the eroding action of the elements, to its present dimensions." If we add to this that between the island and the coast of Africa, in a south-easterly direction, is a profound oceanic gulf known to reach a depth of 2,860 fathoms, or 17,160 feet, while an equally deep, or perhaps deeper, ocean, extends to the west and south-west, we shall be satisfied that St. Helena is a true oceanic island, and that it owes none of its peculiarities to a former union with any continent or other distant land.

Change Effected by European Occupation.—When first discovered, in the year 1501, St. Helena was densely covered with a luxuriant forest vegetation, the trees overhanging the seaward precipices and covering every part of the surface with an evergreen mantle. This indigenous vegetation has been almost wholly destroyed; and although an immense number of foreign plants have been introduced, and have more or less completely established themselves, yet the general aspect of the island is now so barren and forbidding that some persons find it difficult to believe that it was once all green and fertile. The cause of the change is, however, very easily explained. The rich soil formed by decomposed volcanic rock and vegetable deposits could only be retained on the steep slopes so long as it was protected by the vegetation to which it in great part owed its origin. When this was destroyed, the heavy tropical rains soon washed away the soil, and has left a vast expanse of bare rock or sterile clay. This irreparable destruction was caused in the first place by goats, which were introduced by the Portuguese in 1513, and increased so rapidly that in 1588, they existed in thousands. These animals are the greatest of all foes to trees, because they eat off the young seedlings, and thus prevent the natural restoration of the forest. They were, however, aided by the reckless waste of man. The East India Company took possession of the island in 1651, and about the year 1700 it began to be seen that the forests were fast diminishing, and required some protection. Two of the native trees, redwood and ebony, were good for tanning, and to save trouble the bark was wastefully stripped from the trunks only, the remainder being left to rot; while in 1709 a large quantity of the rapidly disappearing ebony was used to burn lime for building fortifications! By the MSS. records quoted in Mr. Melliss' interesting volume on St. Helena,[119] it is evident that the evil consequences of allowing the trees to be destroyed were clearly foreseen, as the following passages show: "We find the place called the Great Wood in a flourishing condition, full of young trees, where the hoggs (of which there is a great abundance) do not come to root them up. But the Great Wood is miserably lessened and destroyed within our memories, and is not near the circuit and length it was. But we believe it does not contain now less than fifteen hundred acres of fine woodland and good ground, but no springs of water but what is salt or brackish, which we take to be the reason that that part was not inhabited when the people first chose out their settlements and made plantations; but if wells could be sunk, which the governor says he will attempt when we have more hands, we should then think it the most pleasant and healthiest part of the island. But as to healthiness, we don't think it will hold so if the wood that keeps the land warm were destroyed, for then the rains, which are violent here, would carry away the upper soil, and it being a clay marl underneath would produce but little; as it is, we think in case it were enclosed it might be greatly improved" ... "When once this wood is gone the island will soon be ruined" ... "We viewed the wood's end which joins the Honourable Company's plantation called the Hutts, but the wood is so destroyed that the beginning of the Great Wood is now a whole mile beyond that place, and all the soil between being washed away, that distance is now entirely barren." (MSS. records, 1716.) In 1709 the governor reported to the Court of Directors of the East India Company that the timber was rapidly disappearing, and that the goats should be destroyed for the preservation of the ebony wood, and because the island was suffering from droughts. The reply was, "The goats are not to be destroyed, being more valuable than ebony." Thus, through the gross ignorance of those in power, the last opportunity of preserving the peculiar vegetation of St. Helena, and preventing the island from becoming the comparatively rocky desert it now is, was allowed to pass away.[120] Even in a mere pecuniary point of view the error was a fatal one, for in the next century (in 1810) another governor reports the total destruction of the great forests by the goats, and that in consequence the cost of importing fuel for government use was 2,729l. 7s. 8d. for a single year! About this time large numbers of European, American, Australian, and South African plants were imported, and many of these ran wild and increased so rapidly as to drive out and exterminate much of the relics of the native flora; so that now English broom gorse and brambles, willows and poplars, and some common American, Cape, and Australian weeds, alone meet the eye of the ordinary visitor. These, in Sir Joseph Hooker's opinion, render it absolutely impossible to restore the native flora, which only lingers in a few of the loftiest ridges and most inaccessible precipices, and is rarely seen except by some exploring naturalist.

This almost total extirpation of a luxuriant and highly peculiar vegetation must inevitably have caused the destruction of a considerable portion of the lower animals which once existed on the island, and it is rather singular that so much as has actually been discovered should be left to show us the nature of the aboriginal fauna. Many naturalists have made small collections during short visits, but we owe our present complete knowledge of the two most interesting groups of animals, the insects, and the land-shells, mainly to the late Mr. T. Vernon Wollaston, who, after having thoroughly explored Madeira and the Canaries, undertook a voyage to St. Helena for the express purpose of studying its terrestrial fauna, and resided for six months (1875-76) in a high central position, whence the loftiest peaks could be explored. The results of his labours are contained in two volumes,[121] which, like all that he wrote, are models of accuracy and research, and it is to these volumes that we are indebted for the interesting and suggestive facts which we here lay before our readers.

Insects—Coleoptera.—The total number of species of beetles hitherto observed at St. Helena is 203, but of these no less than seventy-four are common and wide-spread insects, which have certainly, in Mr. Wollaston's opinion, been introduced by human agency. There remain 129 which are believed to be truly aborigines, and of these all but one are found nowhere else on the globe. But in addition to this large amount of specific peculiarity (perhaps unequalled anywhere else in the world) the beetles of this island are equally remarkable for their generic isolation, and for the altogether exceptional proportion in which the great divisions of the order are represented. The species belong to thirty-nine genera, of which no less than twenty-five are peculiar to the island; and many of these are such isolated forms that it is impossible to find their allies in any particular country. Still more remarkable is the fact, that more than two-thirds of the whole number of indigenous species are Rhyncophora or weevils, while more than two-fifths (fifty-four species) belong to one family, the Cossonidæ. Now although the Rhyncophora are an immensely numerous group and always form a large portion of the insect population, they nowhere else approach such a proportion as this. For example, in Madeira they form one-sixth of the whole of the indigenous Coleoptera, in the Azores less than one-tenth, and in Britain one-seventh. Even more interesting is the fact that the twenty genera to which these insects belong are every one of them peculiar to the island, and in many cases have no near allies elsewhere, so that we cannot but look on this group of beetles as forming the most characteristic portion of the ancient insect fauna. Now, as the great majority of these are wood borers, and all are closely attached to vegetation and often to particular species of plants, we might, as Mr. Wollaston well observes, deduce the former luxuriant vegetation of the island from the great preponderance of this group, even had we not positive evidence that it was at no distant epoch densely forest-clad. We will now proceed briefly to indicate the numbers and peculiarities of each of the families of beetles which enter into the St. Helena fauna, taking them, not in systematic order, but according to their importance in the island.

1. Rhyncophora.—This great division includes the weevils and allied groups, and, as above stated, exceeds in number of species all the other beetles of the island. Four families are represented; the Cossonidæ, with fifteen peculiar genera comprising fifty-four species, and one minute insect (Stenoscelis hylastoides) forming a peculiar genus, but which has been found also at the Cape of Good Hope. It is therefore impossible to say of which country it is really a native, or whether it is indigenous to both, and dates back to the remote period when St. Helena received its early emigrants. All the Cossonidæ are found in the highest and wildest parts of the island where the native vegetation still lingers, and many of them are only found in the decaying stems of tree-ferns, box-wood, arborescent Compositæ, and other indigenous plants. They are all pre-eminently peculiar and isolated, having no direct affinity to species found in any other country. The next family, the Tanyrhynchidæ, has one peculiar genus in St. Helena, with ten species. This genus (Nesiotes) is remotely allied to European, Australian, and Madeiran insects of the same family: the habits of the species are similar to those of the Cossonidæ. The Trachyphlœidæ are represented by a single species belonging to a peculiar genus not very remote from a European form. The Anthribidæ again are highly peculiar. There are twenty-six species belonging to three genera, all endemic, and so extremely peculiar that they form two new subfamilies. One of the genera, Acarodes, is said to be allied to a Madeiran genus.

2. Geodephaga.—These are the terrestrial carnivorous beetles, very abundant in all parts of the world, especially in the temperate regions of the northern hemisphere. In St. Helena there are fourteen species belonging to three genera, one of which is peculiar. This is the Haplothorax burchellii, the largest beetle on the island, and now very rare. It resembles a large black Carabus. There is also a peculiar Calosoma, very distinct, though resembling in some respects certain African species. The rest of the Geodephaga, twelve in number, belong to the wide-spread genus Bembidium, but they are altogether peculiar and isolated, except one, which is of European type, and alone has wings, all the rest being wingless.

3. Heteromera.—This group is represented by three peculiar genera containing four species, with two species belonging to European genera. They belong to the families Opatridæ, Mordellidæ, and Anthicidæ.

4. Brachyelytra.—Of this group there are six peculiar species belonging to four European genera—Homalota, Philonthus, Xantholinus, and Oxytelus.

5. Priocerata.—The families Elateridæ and Anobiidæ are each represented by a peculiar species of a European genus.

6. Phytophaga.—There are only three species of this tribe, belonging to the European genus Longitarsus.

7. Lamellicornis.—Here are three species belonging to two genera. One is a peculiar species of Trox, allied to South African forms; the other two belong to the peculiar genus Melissius, which Mr. Wollaston considers to be remotely allied to Australian insects.

8. Pseudo-trimera.—Here we have the fine lady-bird Chilomenus lunata, also found in Africa, but apparently indigenous in St. Helena; and a peculiar species of Euxestes, a genus only found elsewhere in Madeira.

9. Trichopterygidæ.—These, the minutest of beetles, are represented by one species of the European and Madeiran genus Ptinella.

10. Necrophaga.—One indigenous species of Cryptophaga inhabits St. Helena, and this is said to be very closely allied to a Cape species.

Peculiarities and Origin of the Coleoptera of St. Helena.—We see that the great mass of the indigenous species are not only peculiar to the island, but so isolated in their characters as to show no close affinity with any existing insects; while a small number (about one-third of the whole) have some relations, though often very remote, with species now inhabiting Europe, Madeira, or South Africa. These facts clearly point to the very great antiquity of the insect fauna of St. Helena, which has allowed time for the modification of the originally introduced species, and their special adaptation to the conditions prevailing in this remote island. This antiquity is also shown by the remarkable specific modification of a few types. Thus the whole of the Cossonidæ may be referred to three types, one species only (Hexacoptus ferrugineus) being allied to the European Cossonidæ though forming a distinct genus; a group of three genera and seven species remotely allied to the Stenoscelis hylastoides, which occurs also at the Cape; while a group of twelve genera with forty-six species have their only (remote) allies in a few insects widely scattered in South Africa, New Zealand, Europe, and the Atlantic Islands. In like manner, eleven species of Bembidium form a group by themselves; and the Heteromera form two groups, one consisting of three genera and species of Opatridæ allied to a type found in Madeira, the other, Anthicodes, altogether peculiar.

Now each of these types may well be descended from a single species which originally reached the island from some other land; and the great variety of generic and specific forms into which some of them have diverged is an indication, and to some extent a measure, of the remoteness of their origin. The rich insect fauna of Miocene age found in Switzerland consists mostly of genera which still inhabit Europe, with others which now inhabit the Cape of Good Hope or the tropics of Africa and South America; and it is not at all improbable that the origin of the St. Helena fauna dates back to at least as remote, and not improbably to a still earlier, epoch. But if so, many difficulties in accounting for its origin will disappear. We know that at that time many of the animals and plants of the tropics, of North America, and even of Australia, inhabited Europe; while during the changes of climate, which, as we have seen, there is good reason to believe periodically occurred, there would be much migration from the temperate zones towards the equator, and the reverse. If, therefore, the nearest ally of any insular group now inhabits a particular country, we are not obliged to suppose that it reached the island from that country, since we know that most groups have ranged in past times over wider areas than they now inhabit. Neither are we limited to the means of transmission across the ocean that now exist, because we know that those means have varied greatly. During such extreme changes of conditions as are implied by glacial periods and by warm polar climates, great alterations of winds and of ocean-currents are inevitable, and these are, as we have already proved, the two great agencies by which the transmission of living things to oceanic islands has been brought about. At the present time the south-east trade-winds blow almost constantly at St. Helena, and the ocean-currents flow in the same direction, so that any transmission of insects by their means must almost certainly be from South Africa. Now there is undoubtedly a South African element in the insect-fauna, but there is no less clearly a European, or at least a north-temperate element, and this is very difficult to account for by causes now in action. But when we consider that this northern element is chiefly represented by remote generic affinity, and has therefore all the signs of great antiquity, we find a possible means of accounting for it. We have seen that during early Tertiary times an almost tropical climate extended far into the northern hemisphere, and a temperate climate to the Arctic regions. But if at this time (as is not improbable) the Antarctic regions were as much ice-clad as they are now it is certain that an enormous change must have been produced in the winds. Instead of a great difference of temperature between each pole and the equator, the difference would be mainly between one hemisphere and the other, and this might so disturb the trade winds as to bring St. Helena within the south temperate region of storms—a position corresponding to that of the Azores and Madeira in the North Atlantic, and thus subject it to violent gales from all points of the compass. At this remote epoch the mountains of equatorial Africa may have been more extensive than they are now, and may have served as intermediate stations by which some northern insects may have migrated to the southern hemisphere.

We must remember also that these peculiar forms are said to be northern only because their nearest allies are now found in the North Atlantic islands and Southern Europe; but it is not at all improbable that they are really widespread Miocene types, which have been preserved mainly in favourable insular stations. They may therefore have originally reached St. Helena from Southern Africa, or from some of the Atlantic islands, and may have been conveyed by oceanic currents as well as by winds.[122] This is the more probable, as a large proportion of the St. Helena beetles live even in the perfect state within the stems of plants or trunks of trees, while the eggs and larvæ of a still larger number are likely to inhabit similar stations. Drift-wood might therefore be one of the most important agencies by which these insects reached the island.

Let us now see how far the distribution of other groups support the conclusions derived from a consideration of the beetles. The Hemiptera have been studied by Dr. F. Buchanan White, and though far less known than the beetles, indicate somewhat similar relations. Eight out of twenty-one genera are peculiar, and the thirteen other genera are for the most part widely distributed, while one of the peculiar genera is of African type. The other orders of insects have not been collected or studied with sufficient care to make it worth while to refer to them in detail; but the land-shells have been carefully collected and minutely described by Mr. Wollaston himself, and it is interesting to see how far they agree with the insects in their peculiarities and affinities.

Land-shells of St. Helena.—The total number of species is only twenty-nine, of which seven are common in Europe or the other Atlantic islands, and are no doubt recent introductions. Two others, though described as distinct, are so closely allied to European forms, that Mr. Wollaston thinks they have probably been introduced and have become slightly modified by new conditions of life; so that there remain exactly twenty species which may be considered truly indigenous. No less than thirteen of these, however, appear to be extinct, being now only found on the surface of the ground or in the surface soil in places where the native forests have been destroyed and the land not cultivated. These twenty peculiar species belong to the following genera: Hyalina (3 sp.), Patula (4 sp.), Bulimus (7 sp.), Subulina (3 sp.), Succinea (3 sp.); of which, one species of Hyalina, three of Patula, all the Bulimi, and two of Subulina are extinct. The three Hyalinas are allied to European species, but all the rest appear to be highly peculiar, and to have no near allies with the species of any other country. Two of the Bulimi (B. auris vulpinæ and B. darwinianus) are said to somewhat resemble Brazilian, New Zealand, and Solomon Island forms, while neither Bulimus nor Succinea occur at all in the Madeira group.

Omitting the species that have probably been introduced by human agency, we have here indications of a somewhat recent immigration of European types which may perhaps be referred to the glacial period; and a much more ancient immigration from unknown lands, which must certainly date back to Miocene, if not to Eocene, times.

Absence of Fresh-water Organisms.—A singular phenomenon is the total absence of indigenous aquatic forms of life in St. Helena. Not a single water-beetle or fresh-water shell has been discovered; neither do there seem to be any water-plants in the streams, except the common water-cress, one or two species of Cyperus, and the Australian Isapis prolifera. The same absence of fresh-water shells characterises the Azores, where, however, there is one indigenous water-beetle. In the Sandwich Islands also recent observations refer to the absence of water-beetles, though here there are a few fresh-water shells. It would appear therefore that the wide distribution of the same generic and specific forms which so generally characterises fresh-water organisms, and which has been so well illustrated by Mr. Darwin, has its limits in the very remote oceanic islands, owing to causes of which we are at present ignorant.

The other classes of animals in St. Helena need occupy us little. There are no indigenous mammals, reptiles, fresh-water fishes or true land-birds; but there is one species of wader—a small plover (Ægialitis sanctæ-helenæ)—very closely allied to a species found in South Africa, but presenting certain differences which entitle it to the rank of a peculiar species. The plants, however, are of especial interest from a geographical point of view, and we must devote a few pages to their consideration as supplementing the scanty materials afforded by the animal life, thus enabling us better to understand the biological relations and probable history of the island.

Native Vegetation of St. Helena.—Plants have certainly more varied and more effectual means of passing over wide tracts of ocean than any kinds of animals. Their seeds are often so minute, of such small specific gravity, or so furnished with downy or winged appendages, as to be carried by the wind for enormous distances. The bristles or hooked spines of many small fruits cause them to become easily attached to the feathers of aquatic birds, and they may thus be conveyed for thousands of miles by these pre-eminent wanderers; while many seeds are so protected by hard outer coats and dense inner albumen, that months of exposure to salt water does not prevent them from germinating, as proved by the West Indian seeds that reach the Azores or even the west coast of Scotland, and, what is more to the point, by the fact stated by Mr. Melliss, that large seeds which have floated from Madagascar or Mauritius round the Cape of Good Hope, have been thrown on the shores of St. Helena and have then sometimes germinated!

We have therefore little difficulty in understanding how the island was first stocked with vegetable forms. When it was so stocked (generally speaking), is equally clear. For as the peculiar coleopterous fauna, of which an important fragment remains, is mainly composed of species which are specially attached to certain groups of plants, we may be sure that the plants were there long before the insects could establish themselves. However ancient then is the insect fauna the flora must be more ancient still. It must also be remembered that plants, when once established in a suitable climate and soil, soon take possession of a country and occupy it almost to the complete exclusion of later immigrants. The fact of so many European weeds having overrun New Zealand and temperate North America may seem opposed to this statement, but it really is not so. For in both these cases the native vegetation has first been artificially removed by man and the ground cultivated; and there is no reason to believe that any similar effect would be produced by the scattering of any amount of foreign seed on ground already completely clothed with an indigenous vegetation. We might therefore conclude à priori, that the flora of such an island as St. Helena would be of an excessively ancient type, preserving for us in a slightly modified form examples of the vegetation of the globe at the time when the island first rose above the ocean. Let us see then what botanists tell us of its character and affinities.

The truly indigenous flowering plants are about fifty in number, besides twenty-six ferns. Forty of the former and ten of the latter are absolutely peculiar to the island, and, as Sir Joseph Hooker tells us, "with scarcely an exception, cannot be regarded as very close specific allies of any other plants at all. Seventeen of them belong to peculiar genera, and of the others, all differ so markedly as species from their congeners, that not one comes under the category of being an insular form of a continental species." The affinities of this flora are, Sir Joseph Hooker thinks, mainly African and especially South African, as indicated by the presence of the genera Phylica, Pelargonium, Mesembryanthemum, Oteospermum, and Wahlenbergia, which are eminently characteristic of southern extra-tropical Africa. The sixteen ferns which are not peculiar are common either to Africa, India, or America, a wide range sufficiently explained by the dust-like spores of ferns, capable of being carried to unknown distances by the wind, and the great stability of their generic and specific forms, many of those found in the Miocene deposits of Switzerland, being hardly distinguishable from living species. This shows, that identity of species of ferns between St. Helena and distant countries does not necessarily imply a recent origin.

The Relation of the St. Helena Compositæ.—In an elaborate paper on the Compositæ,[123] Mr. Bentham gives us some valuable remarks on the affinities of the seven endemic species belonging to the genera Commidendron, Melanodendron, Petrobium, and Pisiadia, which forms so important a portion of the existing flora of St. Helena. He says: "Although nearer to Africa than to any other continent, those composite denizens which bear evidence of the greatest antiquity have their affinities for the most part in South America, while the colonists of a more recent character are South African." ... "Commidendron and Melanodendron are among the woody Asteroid forms exemplified in the Andine Diplostephium, and in the Australian Olearia. Petrobium is one of three genera, remains of a group probably of great antiquity, of which the two others are Podanthus in Chile and Astemma in the Andes. The Pisiadia is an endemic species of a genus otherwise Mascarene or of Eastern Africa, presenting a geographical connection analogous to that of the St. Helena Melhaniæ,[124] with the Mascarene Trochetia."

Whenever such remote and singular cases of geographical affinity as the above are pointed out, the first impression is to imagine some mode by which a communication between the distant countries implicated might be effected; and this way of viewing the problem is almost universally adopted, even by naturalists. But if the principles laid down in this work and in my Geographical Distribution of Animals are sound, such a course is very unphilosophical. For, on the theory of evolution, nothing can be more certain than that groups now broken up and detached were once continuous, and that fragmentary groups and isolated forms are but the relics of once widespread types, which have been preserved in a few localities where the physical conditions were especially favourable, or where organic competition was less severe. The true explanation of all such remote geographical affinities is, that they date back to a time when the ancestral group of which they are the common descendants had a wider or a different distribution; and they no more imply any closer connection between the distant countries the allied forms now inhabit, than does the existence of living Equidæ in South Africa and extinct Equidæ in the Pliocene deposits of the Pampas, imply a continent bridging the South Atlantic to allow of their easy communication.

Concluding Remarks on St. Helena.—The sketch we have now given of the chief members of the indigenous fauna and flora of St. Helena shows, that by means of the knowledge we have obtained of past changes in the physical history of the earth, and of the various modes by which organisms are conveyed across the ocean, all the more important facts become readily intelligible. We have here an island of small size and great antiquity, very distant from every other land, and probably at no time very much less distant from surrounding continents, which became stocked by chance immigrants from other countries at some remote epoch, and which has preserved many of their more or less modified descendants to the present time. When first visited by civilised man it was in all probability far more richly stocked with plants and animals, forming a kind of natural museum or vivarium in which ancient types, perhaps dating back to the Miocene period, or even earlier, had been saved from the destruction which has overtaken their allies on the great continents. Unfortunately many, we do not know how many, of these forms have been exterminated by the carelessness and improvidence of its civilised but ignorant rulers; and it is only by the extreme ruggedness and inaccessibility of its peaks and crater-ridges that the scanty fragments have escaped by which alone we are able to obtain a glimpse of this interesting chapter in the life-history of our earth.

119 ^ St. Helena: a Physical, Historical, and Topographical Description of the Island, &c. By John Charles Melliss, F.G.S., &c. London: 1875.

120 ^ Mr. Marsh in his interesting work entitled The Earth as Modified by Human Action (p. 51), thus remarks on the effect of browsing quadrupeds in destroying and checking woody vegetation.—"I am convinced that forests would soon cover many parts of the Arabian and African deserts if man and domestic animals, especially the goat and the camel, were banished from them. The hard palate and tongue, and strong teeth and jaws of this latter quadruped enable him to break off and masticate tough and thorny branches as large as the finger. He is particularly fond of the smaller twigs, leaves, and seed-pods of the Sont and other acacias, which, like the American robinia, thrive well on dry and sandy soils, and he spares no tree the branches of which are within his reach, except, if I remember right, the tamarisk that produces manna. Young trees sprout plentifully around the springs and along the winter water-courses of the desert, and these are just the halting stations of the caravans and their routes of travel. In the shade of these trees annual grasses and perennial shrubs shoot up, but are mown down by the hungry cattle of the Bedouin as fast as they grow. A few years of undisturbed vegetation would suffice to cover such points with groves, and these would gradually extend themselves over soils where now scarcely any green thing but the bitter colocynth and the poisonous foxglove is ever seen."

121 ^ Coleoptera Sanctæ Helenæ, 1877; Testacea Atlantica, 1878.

122 ^ On Petermann's map of Africa, in Stieler's Hand-Atlas (1879), the Island of Ascension is shown as seated on a much larger and shallower submarine bank than St. Helena. The 1,000 fathom line round Ascension encloses an oval space 170 miles long by 70 wide, and even the 300 fathom line, one over 60 miles long; and it is therefore probable that a much larger island once occupied this site. Now Ascension is nearly equidistant between St. Helena and Liberia, and such an island might have served as an intermediate station through which many of the immigrants to St. Helena passed. As the distances are hardly greater than in the case of the Azores, this removes whatever difficulty may have been felt of the possibility of any organisms reaching so remote an island. The present island of Ascension is probably only the summit of a huge volcanic mass, and any remnant of the original fauna and flora it might have preserved may have been destroyed by great volcanic eruptions. Mr. Darwin collected some masses of tufa which were found to be mainly organic, containing, besides remains of fresh-water infusoria, the siliceous tissue of plants! In the light of the great extent of the submarine bank on which the island stands, Mr. Darwin's remark, that—"we may feel sure, that at some former epoch, the climate and productions of Ascension were very different from what they are now,"—has received a striking confirmation. (See Naturalist's Voyage Round the World, p. 495.)

123 ^ "Notes on the Classification, History, and Geographical Distribution of Compositæ."—Journal of the Linnean Society, Vol. XIII. p. 563 (1873).

124 ^ The Melhaniæ comprise the two finest timber trees of St. Helena, now almost extinct, the redwood and native ebony.