CHAPTER XI.

THE FUGUE ON MORE THAN ONE SUBJECT.

365. Having in the preceding chapters of this book fully explained the construction of those fugues which, being founded on only one subject, are sometimes termed "simple" fugues, we have in this chapter to speak of the important class which contains two, three, and occasionally even more subjects. We shall first deal with the Double Fugue, in which, as its name indicates, there are two subjects.

366. In speaking of the countersubject, we incidentally mentioned (§ 175) that some theorists speak of a fugue in which the subject is regularly accompanied by the same countersubject as a "double fugue." If, however, we adopt this nomenclature, we have no means of distinguishing between fugues with one subject and fugues with two or more. It is very much better and clearer to restrict the name of double fugue to two classes of fugue now to be described:—First, those in which the two subjects are announced simultaneously; and, secondly, those in which each subject has a separate and complete exposition before the two are heard in combination. Of these, the first kind is by far the more common and the more important; we therefore deal with it first.

367. A fundamental distinction between the kind of double fugue we are now noticing, and the fugue with a regular countersubject (with which the student is already familiar) is, that in the latter the countersubject never appears before the first entry of the answer, and, as we have seen (§ 172), not always then. But in a double fugue the second subject, which is really a countersubject of the first, accompanies the leading subject on its first entry. This, as we shall see presently, makes a difference (sometimes a very considerable difference) in the form of the exposition.

368. It ought to be hardly necessary to remind students that the two subjects of a double fugue must be written in some kind of double counterpoint with one another. In the enormous majority of cases, this will be double counterpoint in the octave. In the 'Kyrie' of Mozart's 'Requiem,' the two subjects (which we quoted in § 175 of Double Counterpoint) are so written as to be capable of inversion both in the octave and in the twelfth. It is also necessary that there should be contrast, both melodic and rhythmic, between the two subjects, so that each may be easily recognized whenever it appears.

369. It is best that a double fugue should be written for at least four voices, and in vocal music this is almost invariably the case. It is nevertheless possible, though less advisable, to write a double fugue with only three parts. In any case, the student will do well to attend to Albrechtsberger's recommendation that a fugue should always have at least one more voice than it has subjects. Thus, a double fugue ought to be in at least three parts, and a triple fugue (with three subjects) in at least four. But in fugues with more than three subjects (which are very rare), this rule is not always observed, probably because in a fugue with four subjects it is seldom that all four are present at once. The object of the extra voice is, to be able to add a free part when all the subjects are going on at the same time.

370. The exposition of a double fugue can be managed in more than one way. In a four-part fugue, the best arrangement is to let two of the voices announce the two subjects, which the other two follow with the two answers by inversion—that is to say, the upper of the two subjects will appear as the lower of the two answers, and vice versa. A few examples will make this quite clear.

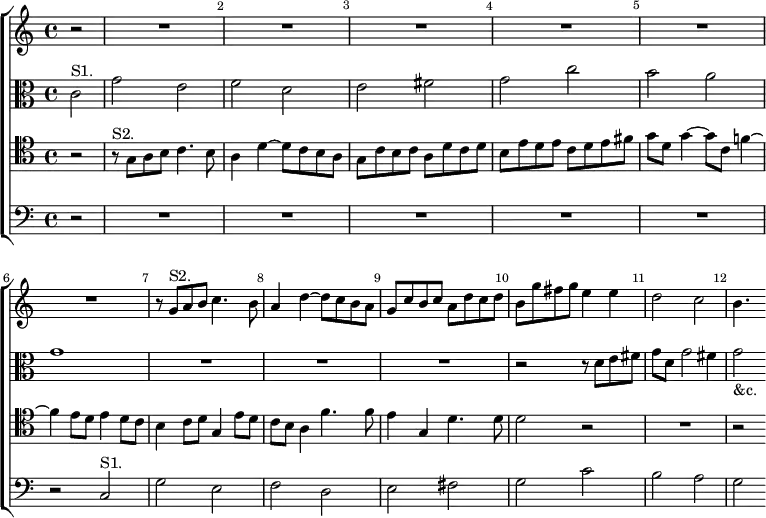

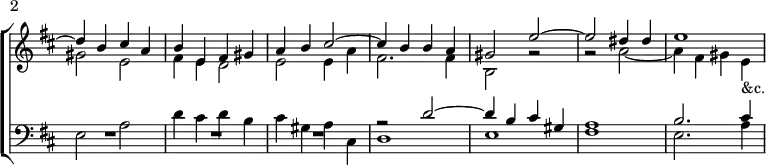

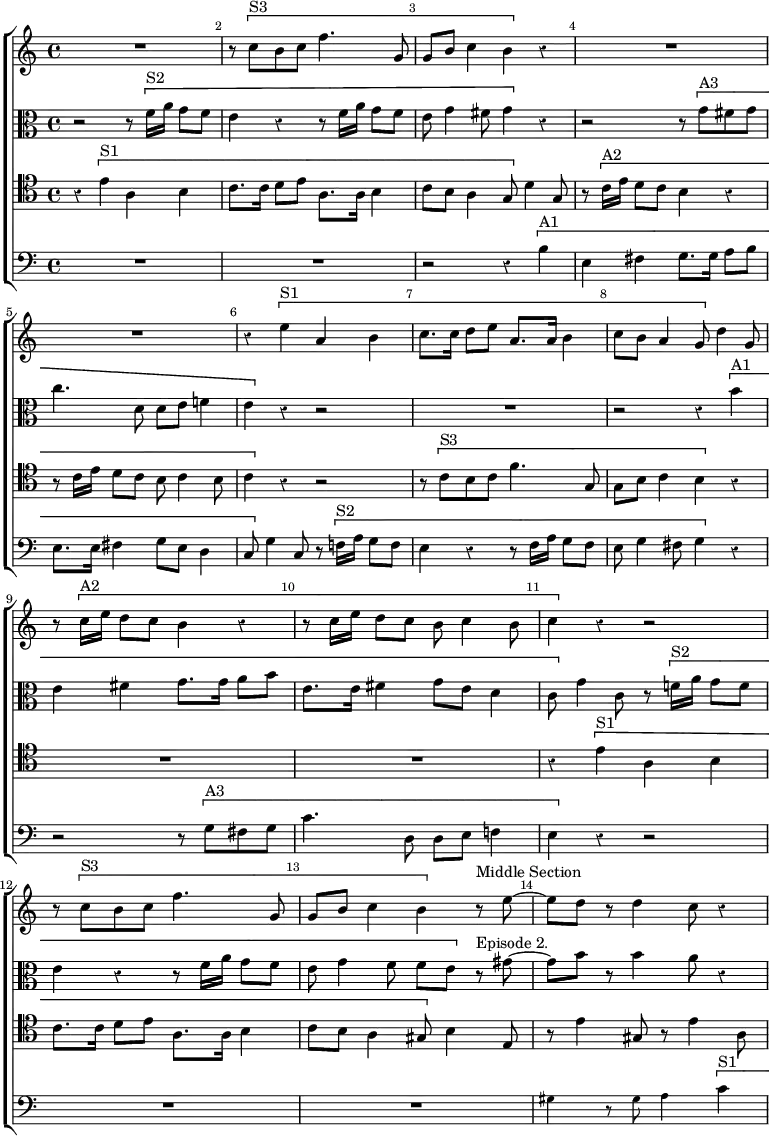

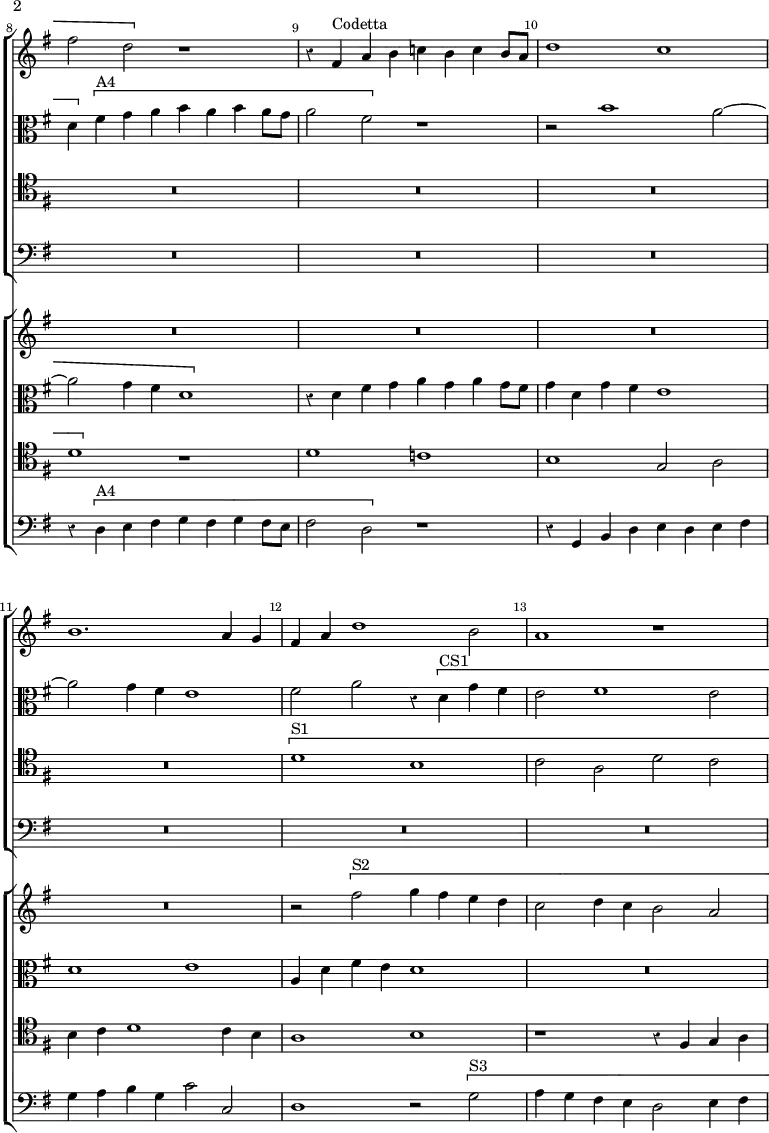

J. S. Bach. Cantata, "Aus der Tiefe rufe ich."

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

\new Staff \relative g' { \key g \minor \time 4/4 \partial 4.

g8^"S1." g f | e4 a d, r8 d' |

g,8 a16 bes c d c bes a8 bes16 c d ees d c |

bes8 c16 d ees f ees d c d c bes a d c d | bes8 g r4 r8 g d g |

g e e a a f f bes | bes g g e a[ fis] }

\new Staff \relative g { \clef alto \key g \minor

r8 r4 | R1*3 | r4 g^"A2." bes b | c cis d2 ~ | d4 cis d_"&c." }

\new Staff \relative d' { \clef tenor \key g \minor

r8 r4 | R1*2 | r8 d^"A1." c bes a4 d |

g, r8 g d ees16 f g a g f |

e8 f16 g a bes a g f8 g16 a bes c bes a |

g a g f e a g a fis8[ d] }

\new Staff \relative g { \clef bass \key g \minor

\tiny g8 bes a | g bes a g f e \normalsize d4^"S2." | ees e f fis

g2. fis4 | g8. \tiny f16 ees d ees c g'4 g, |

c a d bes' | g e8 a d,4 } >>](../../I/a52920bb0be7517503e94dece3d2f181.png.webp)

The small notes on the bass staff here show the instrumental bass; the bass voices have only the second subject, which is printed in large notes. Here the two subjects are announced by the outer voices; when the middle parts bring in the answers, the two themes are inverted in the octave. Notice that the two subjects do not begin simultaneously. It is extremely rare for this to happen. Frequently the second commences only a crotchet, or even a quaver, after the first; but it is undesirable that they should start together, as it would make it more difficult to distinguish them. The counterpoint in the treble of the last two bars is, as will be seen, a free part.

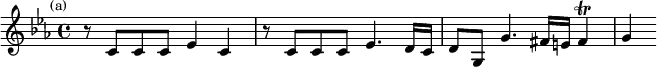

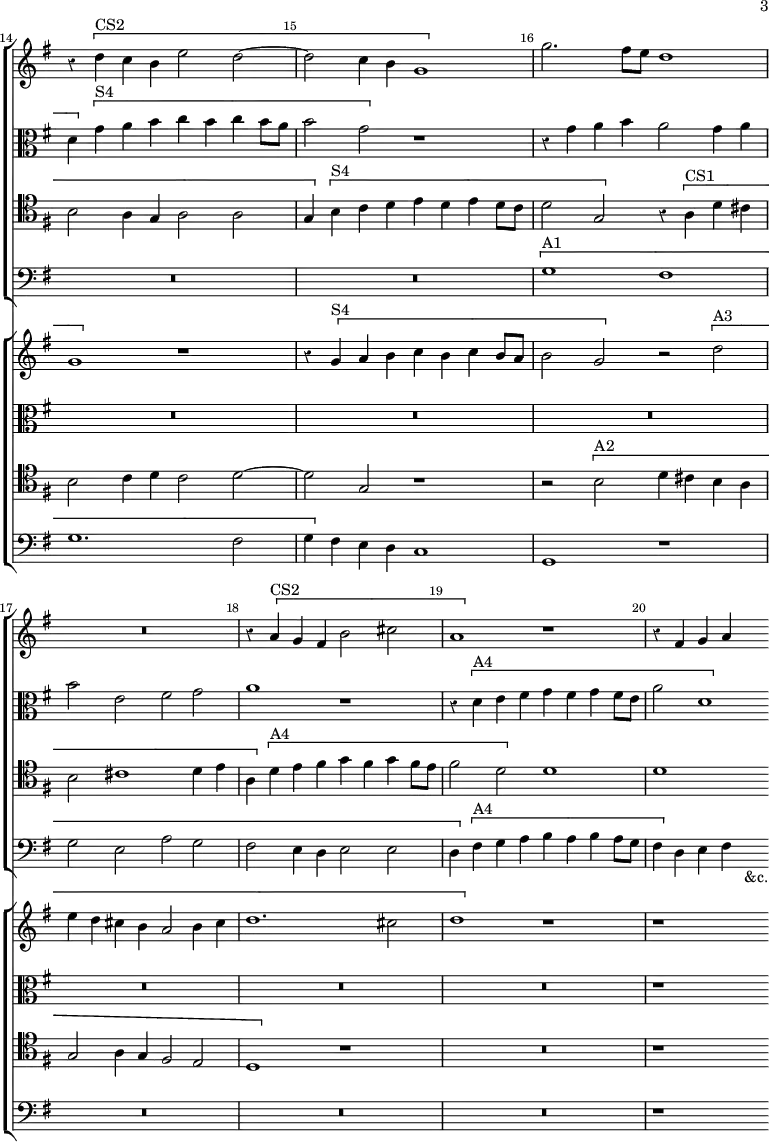

371. In our next example,

Handel. Six Fugues for Harpischord, No. 1.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

\new Staff = "Upper" \relative a'' { \key g \minor \time 4/4

<< { s1 s s s s s r8^"A2." a a a bes bes a g |

a d,16 cis d4 ~ d8 cis d e | f4. } \\

{ s1 s r8 d,_"S2." d d ees ees d c |

d \change Staff = "Lower" \stemUp g, \change Staff = "Upper" \stemDown g'4 ~ g fis | g2 f4 g | a a a g | a8 g f \change Staff = "Lower" \stemUp e d4 e | cis8 e a,4 e'4. g,8 | a[ d a]^"&c." } \\

{ r4 d'^"S1." g, a | bes a8 g ees'2\trill | d4. d8 g,4 c ~ |

c bes a8 bes16 c d8 c | bes a bes c16 bes a8 d ~ d cis |

d e16 d e8 f d2 | cis \stemDown b8\rest d cis b |

a4. bes16 a g2 | f4. } >> }

\new Staff = "Lower" \relative g { \clef bass \key g \minor

R1 R s s | r4 \stemDown g^"A1." d e | f e8 d bes'2\trill |

a4. a8 d,4 g ~ | g f e2 d4. } >>](../../I/603fce0fdaef54f6a528f155658cf32c.png.webp)

the order of entry of the preceding is reversed. Here the two middle voices have the subjects and the outer ones the answers. Note in the answer in the treble the change of an octave in pitch (§ 154) to keep the music within the reach of the hands. The alteration at the end of both the answers is an illustration of what has been more than once mentioned—that Handel's fugue writing is usually much more free than Bach's.

372. It is not always necessary that the two voices which enter with the answers should be in the opposite relative positions to those which announce the subjects. Sometimes the part which was the higher at first is still the higher, as in the following example.

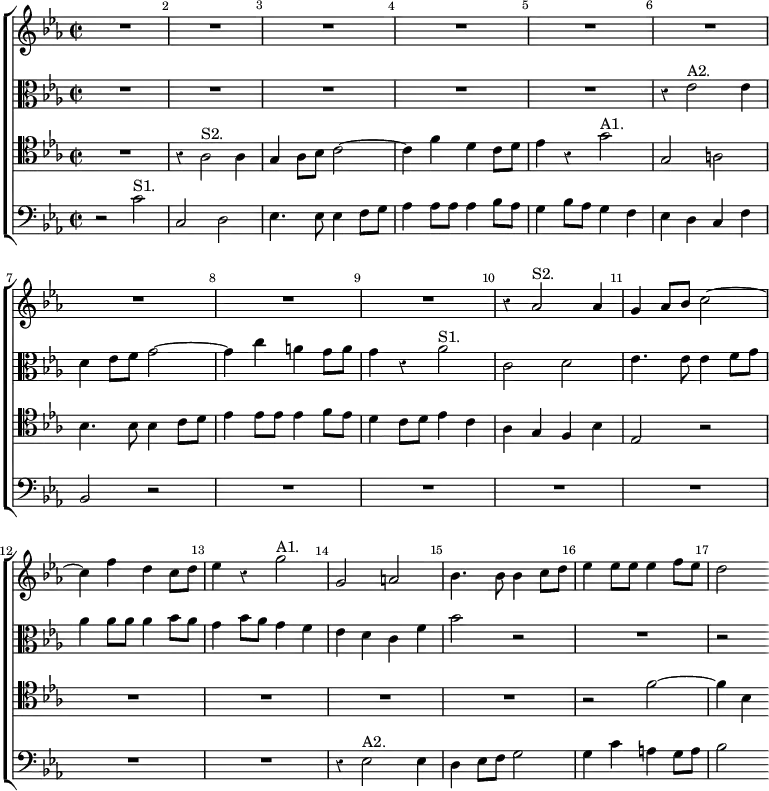

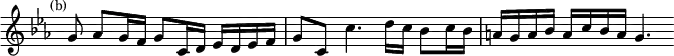

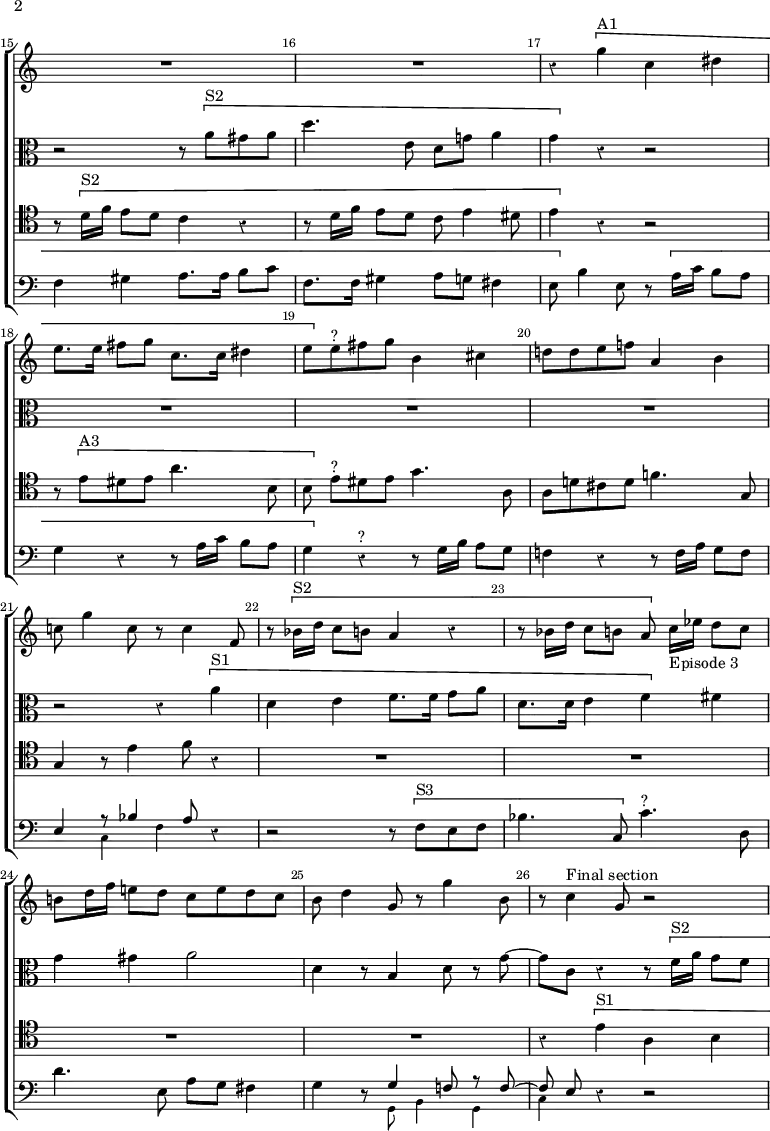

Haydn. 1st Mass.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.BarNumber.break-visibility = ##(#f #t #t) \set Score.barNumberVisibility = #all-bar-numbers-visible

\new Staff \relative f'' { \key bes \major \time 4/4

f2^"S1." d4 bes8 bes | g a bes c16 d ees2 |

d4 f8 ees16 d c4. c8 | d4 c bes8 c d e | f4 r r2 | R1*4

f2^"S1." d4 bes8 bes | g a bes c16 d ees2 | d c | bes4 s }

\new Staff \relative a' { \key bes \major \clef alto

R1*2 bes2^"A1." a4 f8 f | d e f g16 a bes2 |

a8^"S2." f g a bes c d c16 d | ees4 d4. g,8 c4 ~ |

c bes r8^"A2 (varied)." f g a | bes4 a2 g8 f |

e4 f2 e4 | f r r2 | r4 bes2 a4 ~ | a g2 fis4 | g2 }

\new Staff \relative f { \clef tenor \key bes \major

r8^"S2." f g a bes c d c16 d | ees4 d c2 | bes4 r r2 | R1

f'2^"S1." d4 bes8 bes | g a bes c16 d ees2 ~ |

ees4 d c a | f8 g a bes16 c d2 | c bes |

a8^"S2." a bes c d ees! f ees16 f |

g4 f ees r8 c | d f r bes, c ees r a, | bes s s4^"&c." }

\new Staff \relative b, { \clef bass \key bes \major

R1*2 r8^"A2." bes d ees f g a g16 a | bes4 a g2 | f4 r r2 R1 |

bes2^"A1." a4 f8 f d e f g16 a bes2 ~ | bes4 a g2 |

f8 f,[^"S2." g a] bes[ c] d[ c16 d] |

ees4 d c f | bes, r8 ees a,4 d | g,8 s s4 } >>](../../I/540fd7907e181ee6e4d3b989bf3051fe.png.webp)

We have here a subject taking a tonal answer; the second subject (which corresponds to the countersubject of a simple fugue) also needs modification (§ 170). We have quoted the whole exposition, as it shows a very frequent manner of commencing a double fugue.

373. After the first entries of the two subjects and answers, we see other entries in the same keys as before, but differently distributed between the voices. At bar 5, the tenor has the first subject, and the alto the second; in the seventh bar the bass has the first answer, and the alto a modified form of part of the second. Lastly, at bar 10, the first subject is seen again in the treble, while bass and tenor both have the second subject, the tenor being written in double counterpoint in the tenth. When an exposition contains only one entry each of the subjects and answers, it will be very brief. This is the case with the example in § 371, where our extract is immediately followed by the first episode; more frequently, as here, additional entries precede the introduction of any episodical matter.

374. Occasionally after two voices have announced the subjects, the other pair, instead of giving the answers, repeat the subjects, but inverted in their relative positions.

Handel. 'Judas Maccabæus.'

It looks at first sight as if the first subject extended to the sixth bar. That this is not the case is proved by the second subject. If bars 4 and 10 are compared, it will be seen that they are quite different. Now it is an important rule in writing a double fugue that, though the two subjects had better begin one after the other, they must always finish together. Bar 10 proves that the second subject ends on the first note of bar 4; consequently the first subject must end at the same point, and bars 5 and 6 must be regarded as codetta.

375. The exposition of a double fugue is sometimes arranged in quite a different manner, which will be best understood by an example.

Hummel. 2nd Mass.

As in the preceding examples, the two subjects are announced together, here by the tenor and bass voices; but instead of the two answers being given by the other two voices, the tenor, which has just completed the second subject, continues with the first answer, the alto entering with the second answer. The bass continues as far as bar 7 with a free counterpoint, and is then silent till it re-enters with the second answer in bar 14.

376. The alto, having completed the second answer, continues with the first subject, while the treble enters with the second subject, going on in its turn with the first answer. This gives the bass the opportunity of bringing in the second answer below the first (as in the additional entry of a simple fugue), and the exposition is completed when both the subjects (or answers) have been heard in each voice.

377. In the above example, each new voice entered first with the second subject. In the following we see the reverse case, all the fresh entries being with the first subject.

Cherubini. 2nd Mass.

After the explanations of the preceding exposition, few words are needful concerning this one. If the student will examine it, he will see that a codetta is introduced before each new pair of entries. The treble, which led with the second subject, makes its final appearance at bar 27 with the first, showing the inversion of the two subjects, just as they were shown at bar 14 of the example by Hummel.

378. Another important point is illustrated by the two expositions just quoted. It will be seen that though both are for four voices, only three are present at any one time, while a considerable part of the exposition in § 375 is for two voices only. We often find this in the exposition of a double fugue; the reason is that it is absolutely necessary that both the subjects shall be clearly and easily distinguished, and this end is attained by leaving them either without any other counterpoint, or with only one added part. Clearness is, if possible, of even more importance in a double fugue than in a fugue with only one subject.

379. The general form of such double fugues as those we are now describing mostly follows the plan shown in Chapter IX. But there are some differences of detail often to be met with that must be mentioned. In the first place we sometimes find less episode in a double than in a simple fugue. For instance, the 'Kyrie' of Mozart's 'Requiem,' one of the finest double fugues ever written, contains only one episode, and that is but a bar and a half in length. When there is so little episode, its place is usually taken by developments of one of the two subjects without the other.

380. In general, both subjects should be heard together in each group of middle entries. Occasionally, we find such an entry for one subject alone; but this is far more exceptional than the entry of a subject in a simple fugue without its countersubject.

381. It is seldom practicable in a double fugue to write a stretto in which both the subjects shall take part. We have already seen with simple fugues that if there is much stretto, there is generally either no countersubject, or, if there be one, it is omitted in the stretti. The obvious reason for this is, that that part of the countersubject which is written against the latter part of the subject can seldom be also made to fit the first part which, in a stretto, will be appearing in another voice; while, if all the voices are joining in the stretto, there will evidently be none left to give the countersubject. As the second subject in a double fugue is virtually a countersubject to the first, it is clear that the same reasoning will apply to it. Consequently the stretti, when there are any, in a double fugue are mostly made from one subject alone, and very often take the place of the episodes.

382. The general rules as to the order of entries, etc., given in § 325, apply also to double fugues, excepting that in the latter there should be no isolated entry for one of the subjects unaccompanied by the other. One entry of the two subjects together may, however, be divided by episodes from the preceding and following.

383. Our space will not allow us to give complete examples here of double fugues, as we did of simple fugues in Chapter IX. In the volume on Fugal Analysis, which will follow the present one, we shall insert some fine specimens of this kind. Meanwhile it is hoped that the explanations given in this chapter will enable the student to understand the construction of a double fugue, and, if necessary, to write one for himself.

384. We have now to speak of the second variety of double fugue—that in which each of the two subjects has its own separate exposition, and it is only in the latter part of the fugue that they appear together. Though some very fine examples of such fugues are to be found, they are far rarer than the kind of which we have been hitherto speaking, and they are constructed after a different plan.

385. It is, of course, just as necessary in this kind of fugue as in the other that the two subjects must be composed together in the first instance, and that they must be in double counterpoint with one another; otherwise it is in the highest degree improbable that it will be possible to combine them. The essential difference between this and the other class of double fugues is, that here the combination, instead of being shown at first, is reserved for the climax, whereby its effect is frequently much increased.

386. There is considerable difference in various fugues of this class as to the amount of separate treatment which each subject receives before they are brought together. Sometimes the first subject will have a regular exposition, and the second only a partial one, as in the following passage, which, to save space, we give in short score.

Handel. 'Dettingen Anthem.

Here the first exposition is separated from the second by a short symphony for the orchestra. In the second exposition, the subject in the alto is answered by the treble; but the bass and tenor have only free imitations of its first notes, and there is no complete exposition of the second subject. After the cadence in G major, the two subjects are combined; but the freer style is soon resumed, as will be seen from the last bars of our quotation.

387. Our next illustration is somewhat more regular in treatment.

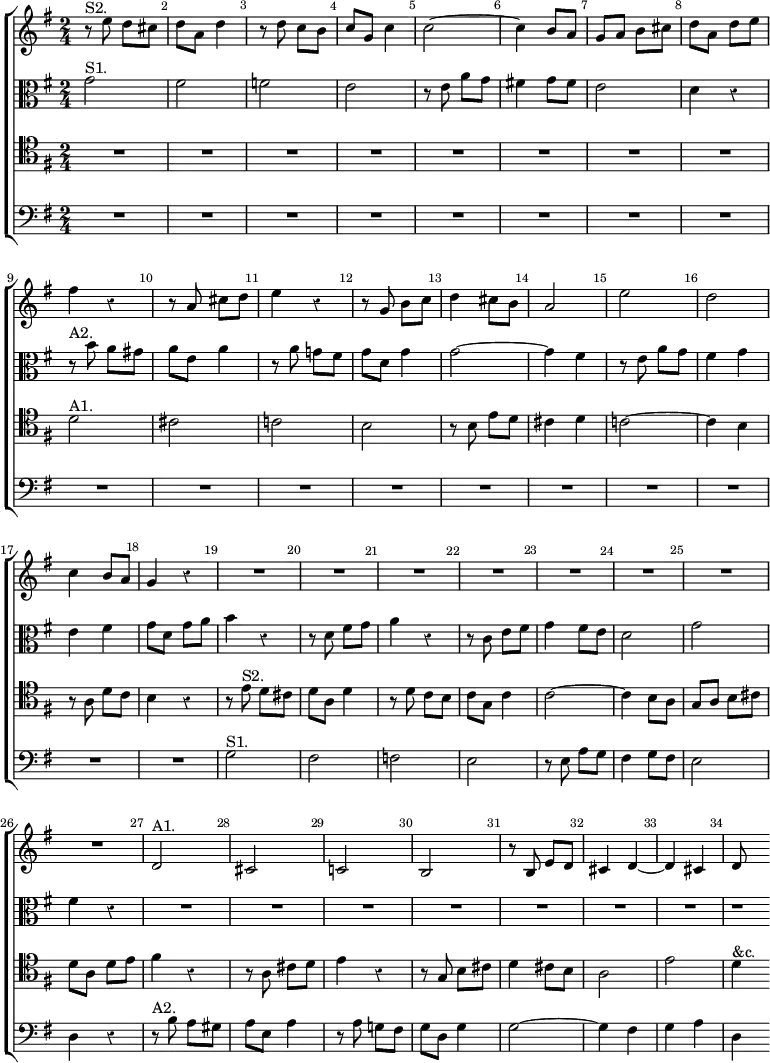

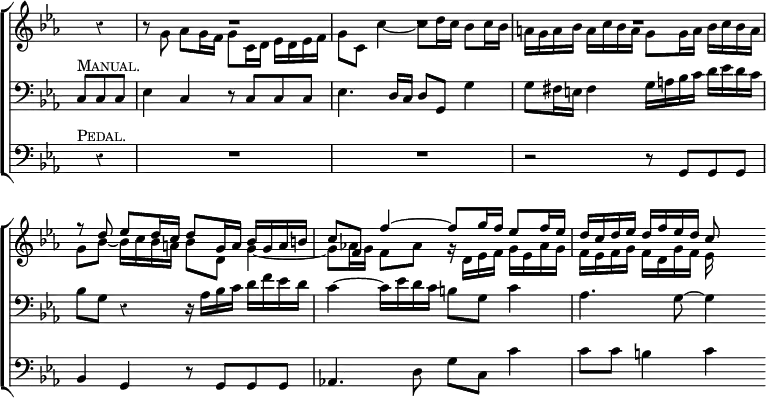

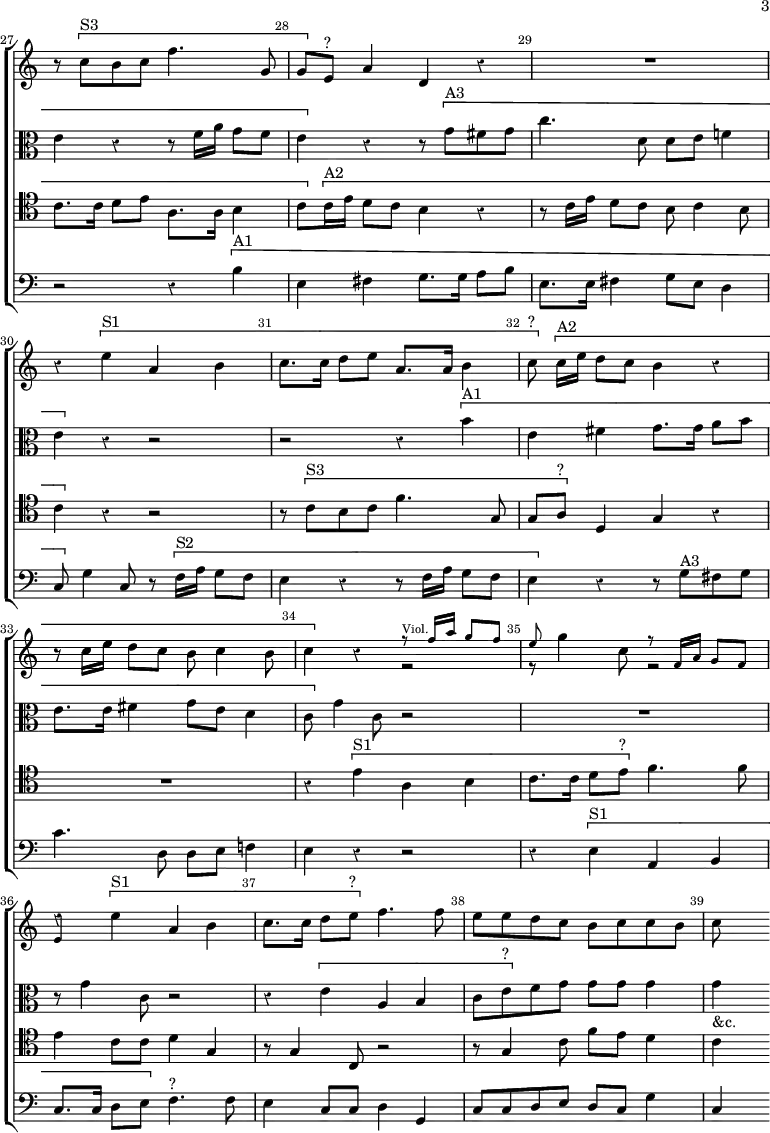

J. S. Bach. Cantata, "Lobe den Herrn, meine Seele."

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

\new Staff <<

\new Voice \relative a' { \key d \major \time 3/4 \partial 8*5 \stemUp

a16 b cis d e cis fis e d cis |

b d cis d e d cis d e d cis b | a cis b a d2 ^~ |

d4. e8 cis4 | d8 cis16 d e8 d cis fis16 e | d4 cis b |

cis16 a b cis d e fis e d cis b a |

b4 ^~ b16 cis a b cis b a g | fis8 }

\new Voice \relative d' { \stemDown

r8 r4 r | r2. | r8 d16 e fis g a fis b a g fis |

e g fis g a g fis g a b fis e | d fis e d a'2 _~ | a4. b8 gis4 |

a8 fis16 g! a8 g fis b16 a | g4 fis e | fis16 s_"&c." } >>

\new Staff <<

\new Voice \relative a { \clef bass \key d \major \stemUp

s8 s2 | s2. s s | r8 a16 b cis d e cis fis e d cis |

b d cis d e d cis d e d cis b | a cis b a d2 ^~ | d4. e8 cis4 d8 }

\new Voice \relative a { \stemDown \tiny

r8 r a[ d, fis] | g4 r8 e[ cis e] | d4 r8 fis[ g e] |

a4 r8 a[ a, a'] | b4 r8 cis[ fis a,] | b4 r8 cis16 d e8 e, | \normalsize

r8 d16 e fis g a fis b a g fis | e g fis g a g fis g a g fis e d s } >> >>](../../I/d5c604ebc243d191bf18e12d53b78166.png.webp)

The subject here (as will be seen later when the two are combined) extends to the D at the beginning of the fifth bar. We have here therefore a "close fugue" (§ 279), though the answer does not enter so immediately after the commencement of the subject as in the examples of this kind of fugue previously given. The small notes on the bass staff show, as in other cases, the real (instrumental) bass of the harmony. We have here a quite regular exposition, of which (to save space) we have omitted the last two bars of the bass entry. In the continuation of the passage there are two instrumental entries—subject (2nd violins), answer (1st violins), making in all an exposition of a six-part fugue.

388. After three bars of interlude for the orchestra, there is a counter-exposition of the first subject. Here the bass leads with the answer and the tenor replies with the subject, all the entries being in the reverse order of that of the first exposition. We exceptionally find here that it is only the order of entry that is reversed; usually a voice that had the answer in the exposition will have the subject in the counter-exposition, and vice versa.

389. The counter-exposition is followed at once by the exposition of the second subject.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f

\new Staff <<

\new Voice \relative e'' { \key d \major \time 3/4 \partial 2

\stemUp r4 r | R2.*6 | r4 e e |

e8 d d4 d | d8 cis cis fis16 e d8 cis |

b e, e' d cis b a8 s4_"&c." }

\new Voice \relative a' { \stemDown s2 | s2. | r4 a a | a8 g g4 g |

g8 fis fis b16 a g8 a e[ a,] a'[ g fis e] |

fis[ gis16 a] b8[ a g fis] | e[ fis16 g] a8[ b cis b] |

a gis fis4 b8 a | gis4 e8 d'16 cis b8 a | e4. fis16 g a8 d, | d } >>

\new Staff <<

\new Voice \relative e' { \clef bass \key d \major \stemUp

e4 e e8 d d4 d | d8 cis cis fis16 e d8 cis |

b e, e' d cis b | a[ b16 cis] d8[ fis e d] |

a'4 ^~ a16 g fis e d8 cis | d4. b8 e4 | a,8[ d cis cis] a[ b] |

cis b16 cis d8 cis b cis16 d | e4 e8 d e fis | b,4 a8 a a4 a4. }

\new Voice \relative c' { \stemDown \tiny

r8 cis16 b a8 gis | fis gis16 a b8 a g e | a b a g! fis e |

d e16 fis e8 fis e d | cis a \normalsize d4 d | d8 cis cis4 cis |

cis8 b b e16 fis e8 d | cis[ b a] gis'16[ b] a8[ gis] |

fis b, b' a gis fis | e[ fis16 gis] a8[ b cis d] |

e[ d cis b] a b16 cis | d4. } >> >>](../../I/cf2f23858c8e1dc07c5ddb1c9820db56.png.webp)

This subject, like the other, is four bars in length; it is also treated in six parts by the addition of entries for two violins; but the irregularity of the intervals of reply show that this exposition belongs to the fugato (§ 358) rather than to strict fugue.

390. To the counter-exposition succeeds immediately the combination of the two subjects, of which we quote the first bars. For the sake of clearness, we here give them in open score.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f

\new Staff \relative a' { \key d \major \time 3/4 \mark \markup \small "(a)"

r8 a16 b cis d e cis fis e d cis | b d cis d e d cis d e d cis b |

a cis b a d2 ~ | d4. e8 cis4 | d8[ fis16 e] d8[ cis b a] |

g e e'4 e | fis16 g e fis g2 ~ | g8[ fis16 e] fis8[ a g fis] | e }

\new Staff \relative a' { \key d \major \clef alto

r4 a a | a8 g g4 g | g8 fis fis b16 a g8 fis | e a, a' b a g |

fis2 fis4 | g e8 a a a | a g16 fis e8 e16 fis g a fis g |

a4 ~ a16 e fis g a g a b | cis s_"&c." }

\new Staff \relative d' { \clef tenor \key d \major

R2.*4 r4 d d | d8 c c4 c | c8 b b e16 d cis8 b |

a d, d' fis e d | cis }

\new Staff \relative a { \clef bass \key d \major

\tiny a16 g a g fis8[ e d b] | e4 r8 e16 d cis8 a |

d d'16 cis b a g fis e fis g e | a e fis g a g fis g a g fis e |

d cis \normalsize d e fis g a fis b a g fis |

e g fis g a g fis g a g fis e | d e cis d e8 fis e d |

cis16 a b cis d cis d e fis e fis g | a8 } >>](../../I/77cfd69242ccde98eca565e12030fd16.png.webp)

It will be seen that modifications are made in the second pair of entries; in bar 7 of our extract the close of the first subject is transferred from the bass to the treble. We have already seen the same thing (§ 271) in the case of a countersubject. A little later we find the two subjects combined in a different manner.

Here the first half of the first subject serves as a counterpoint to the second half of the second subject—a combination which we just now remarked (§ 381) was very seldom possible. But almost anything seems to have been possible to Bach. The whole fugue which we have been describing is a marvel of scientific contrivance, though we do not recommend students to imitate the consecutive seconds seen in the last bar but one of our last example.

391. One of the most perfect examples, as regards its form, of this kind of double fugue is an organ fugue by Bach in C minor. The piece is too long to quote here; it will be found in the Peter's Edition of Bach's Organ Works, Vol. IV., p. 36, to which we refer the student, confining ourselves here to a short analysis of the piece. It will be seen to differ considerably from the examples already described.

392. The first subject of the fugue, which is in four parts, is

J. S. Bach. Organ Fugue in C minor.

This subject receives a regular exposition (bars 1–14) followed by an episode of four bars. To this succeed four isolated entries in the keys of G minor (bar 18), E flat major (bar 23), and C minor (bars 29 and 34). After a full close in G minor, with the "Tierce de Picardie," the second subject is announced (bar 37):

This subject, like the first, has a complete exposition, the second and third entries of which are divided by a codetta (bars 42, 43). This second exposition ends in bar 49, and is followed by entries of subject or answer in G minor (bar 49), C minor (bar 52), F minor (bar 55), C minor (bar 57); then, after an episode (bars 60 to 63), C minor again (bar 63), and an altered entry (bars 66 to 69), partly in F minor, and partly in C minor.

393. At bar 70 the two subjects appear together tor the first time. We quote the first two entries.

J. S. Bach. Organ Fugue, in C minor.

The modifications in the tonal answers will be easily understood if Chapter IV. of this volume has been thoroughly mastered. It will be seen that the figures of semiquavers have been simplified for the pedals. This is probably less because of their technical difficulty than because of the very practical reason that the lower notes of the pedal organ cannot be depended on to speak with sufficient rapidity. When the second subject (the more florid of the two) is given to the pedals, as at bars 77 and 88, it is even more simplified than the first subject.

394. The fugue we are now examining contains five entries subsequent to those last quoted. All of them are either in the tonic or dominant key, and in all both the subjects appear in their complete shape. A coda of six bars (bars 99 to 104) concludes the movement.

395. By comparing this fugue with those we have previously spoken of, we see what may be approximately described as the limits of variation in the form now under notice. In both our earlier examples, the second exposition followed immediately on the first,—in the case of the fugue in "Lobe den Herrn, meine Seele," after the counter-exposition. In the C minor fugue, on the contrary, each subject has a considerable amount of working out before the next is introduced. In the fugues in §§ 386, 387, the combination of the two subjects followed close after the second exposition; here it is not so. In fact, it is left entirely to the judgment of the composer in a fugue of this kind, how much development he will give to each of his subjects separately before he proceeds to treat them in combination.

396. A double fugue of this class, like a simple fugue, is in ternary form; but its three sections are different from those of a simple fugue which we showed in Chap. IX. A fugue of the kind now under notice will contain the three following sections:—

(1) Treatment of first subject separately.

(2) Treatment of second subject separately.

(3) Treatment of both subjects combined.

We have already said that it is optional how much each section contains.

397. There is one more point to be noticed with respect to this variety of fugue. Owing to the fact that both the subjects will have their expositions in the original keys of tonic and dominant, we usually find very little modulation in a fugue of this sort. As a striking illustration of this, take the fugue in C minor which we have just analyzed. Not counting the expositions, it contains in all fifteen entries, either of the single subjects or of the two together. Of these, twelve are either in C minor or in G minor. Only three (one fifth of the whole) are in any other key. It is quite possible, as Bach conclusively proves in this masterly fugue, to obtain variety by other means than incessant modulation.

398. A Triple Fugue, that is, a fugue with three subjects, is very much rarer than a fugue with two, and when we find one, it is seldom strict. The first requisite for such a composition is, that the three subjects must be written in triple counterpoint, as each will in turn have to do duty as a bass. It is also needful that all the subjects be well contrasted in character, as we have already seen that they should be in the case of a double fugue.

399. It is possible to write a triple fugue after the second of the two methods above shown for a double fugue, that is to say, to give each of the three subjects a separate exposition before combining them. But this plan is seldom adopted, probably owing to the length to which it will cause the composition to extend. A striking illustration of this is seen in the final fugue in Bach's 'Art of Fugue,' of which we will here give a short account before proceeding to speak of the more common kind of triple fugue.

400. The fugue now to be noticed, one of Bach's latest compositions, was unfortunately never completed, being interrupted by the composer's blindness, which shortly preceded his death. Enough, however, exists to show the scope of the whole work. We first give the exposition of the first subject.

J. S. Bach. 'Art of Fugue.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.BarNumber.break-visibility = ##(#f #t #t) \set Score.barNumberVisibility = #all-bar-numbers-visible

\new Staff \relative a' { \key d \minor \time 4/4

R1*15 r2 \[ a^"A1" d2. d4 | c1 | d |

e | a,2. \] b4 c2. d4 | g,2 fis g gis |

a8 c4 b8 c2 ~ | c4 b8 a b2 | c4 bes a g | fis2. g8 a | g2. s4 }

\new Staff \relative d' { \clef alto \key d \minor

R1*10 r2 \[ d^"S1" a'2. g4 | f1 g |

a d, ~ \] d2 e ~ | d4 c f2 ~ | f4 d g2 ~ |

g4 e a g ~ | g f8 e f2 | e4 d8 e f2 ~ | f4 ees2 d4 ~ | d8 e f2 e8 d

c4 d e2 | d2. e8 f | e4 d c2 ~ | c4 d8 ees d2 ~ | d4 e8 fis a2_"&c." }

\new Staff \relative a { \clef tenor \key d \minor

R1*5 r2 \[ a^"A1" | d2. d4 | c1

d e a,2 \] d ~ | d cis | d4 a bes2 ~ | bes4 g c2 ~ |

c4 a d c ~ | c bes a2 ~ | a4 b8 c b2 | a2. a4 | bes2. b4 |

c2 cis | d4 a d2 | c r R1 r2 \[ d,^"S1"

a'2. g4 | f1 | g a | d,2. \] s4 }

\new Staff \relative d { \clef bass \key d \minor

r2 \[ d^"S1" a'2. g4 | f1 g a d,2 \] f ~ | f4 b, e2 | a,4 e' a g |

f d bes' a | g e cis d8 e | f4 d c bes | a g a2 | d,2. d'4 | e2. d8 e |

f2 fis | g2. fis8 e | fis2 gis a r R1

R1 r2 \[ d,^"S1 (inverted)." a2. b4 | c1 bes

a d \] c4 d ees2 ~ | ees4 a, d c | b2 bes } >>](../../I/6c2cf5f984cc17892f06e2c2584a6e90.png.webp)

After the entry of the answer in the treble (bar 16), we have in bar 21 the inverted subject in the bass, imitated in stretto and in direct motion by the tenor in bar 24. This subject is henceforth treated both by direct and inverse motion, and mostly in stretto at two or one bar's distance till bar 114, at which point a full close is made in the tonic key. We have thus far a fugue on one subject complete in itself, and the whole piece might end here. Bach, however, makes his cadence the starting point for a new departure.

401. We give the cadence closing the first part of the fugue, and the commencement of the second exposition, which is too long to quote in its entirety.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.BarNumber.break-visibility = ##(#f #t #t) \set Score.barNumberVisibility = #all-bar-numbers-visible \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \set Score.currentBarNumber = #112

\new Staff \relative e'' { \key d \minor \time 4/4 \mark \markup \tiny { (\italic"a") }

e2 d ~ | d cis | d4 a ~ a g | f r r2 | R1*5 |

r4 \[ c'8^"A2" d c b a gis | a e a b c b a c | b e, b' c d c16 b c8 d

e d c d e2 ~ | e8 d16 cis d8 e f2 ~ | f8 e d c b a b d |

c \] a' g f e d e g | f e d cis d4 e | a,2. b4 }

\new Staff \relative c'' { \clef alto \key d \minor

cis4 a2 g8 f | g4 e ~ e8 f g4 ~ | g \[ f8^"S2" g f e d cis |

d a d e f e d f | e a, e' f g f16 e f8 g | a g f g a2 ~ |

a8 g16 fis g8 a bes2 ~ | bes8 a g f e d e g |

f \] e d c b a b d | c b a gis a4 b | c4. d8 e4 fis | g gis2 a4 ~

a8 f e d c b a g | f g' f e d c b a | gis4 a2 gis4 |

a b c cis | d a'2 g4 ~ | g f8 e d4 g_"&c." }

\new Staff \relative g { \clef tenor \key d \minor

g4 f8 e f4 d | e f8 g a2 ~ | a4 d bes2 | a4 r r2 | R1*14 }

\new Staff \relative a, { \clef bass \key d \minor

a1 ~ a | d ~ d4 r r2 | R1*12 |

r4 \[ f8^"S2" g f e d cis | d a d e f e d f } >>](../../I/ded2531ca0737b234732914a99f7b317.png.webp)

This exposition ends at bar 141, and, after an episode of five bars, the first and second subjects are combined thus:—

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.BarNumber.break-visibility = ##(#f #t #t) \set Score.barNumberVisibility = #all-bar-numbers-visible \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \set Score.currentBarNumber = #147

\new Staff \relative f'' { \key d \minor \time 4/4 \mark \markup \tiny {(\italic b )} \bar ""

r4 \[ f8^"S2" g f e d cis | d a d e f e d f |

e a, e' f g f16 e f8 g | a g f g a2 ~ | a8 g16 fis g8 a bes2 ~ |

bes8 a g f e d e g | f \] e d c b a b d | c4 }

\new Staff \relative f' { \clef alto \key d \minor

f8 a d,4 r2 | R1*6 r4 }

\new Staff \relative d { \clef tenor \key d \minor

d4 a' bes2 | a4 b8 cis d2 ~ | d4 cis8 d e2 ~ |

e8 a, d4 ~ d8 c bes a | bes d ees4 ~ ees8 d cis d |

cis4 d2 c4 ~ | c b8 a gis fis gis b | a[ e']^"&c." }

\new Staff \relative d { \clef bass \key d \minor

d2. e4 | f2 \[ d^"S1" a'2. g4 | f1 g a d,2 \] e | a,4 } >>](../../I/6ed192e9deb864706258ce1980b3b25e.png.webp)

Later in the fugue (bars 167 to 173) the two subjects are combined in a different manner, the first subject being now introduced, not against the second, but against the third bar of the second subject. The end of the second section of the fugue shows another ingenious device. Above the second subject (in the bass) the first is introduced by treble and alto in stretto at one bar's distance, one entry being on the third and the other on the fourth bar of the second subject.

402. The second section of the fugue closes in G minor, and at bar 193 the third subject, made from the composer's name, is introduced. For the sake of those who do not understand German, it will be well to say that in Germany the note B flat is simply called B, and B natural is named H. We now give the third exposition.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.BarNumber.break-visibility = ##(#f #t #t) \set Score.barNumberVisibility = #all-bar-numbers-visible \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \set Score.currentBarNumber = #192

\new Staff \relative g' { \key d \minor \time 4/4 \mark \markup \tiny {(\italic a )} \bar ""

g4. a8 fis4. g8 | g2 r | R1*7 | r2 \[ bes^"S3" a c b4. cis8 d2 ~ |

d4. cis16 b cis2 | d4 \] r r dis | e b e d | c2 }

\new Staff \relative g' { \clef alto \key d \minor

g8 f ees4 d c ~ | c bes r2 | R1 | r2 \[ f'^"A3" |

e2 g | fis4. gis8 a2 ~ | a4. gis16 fis gis2 a4 \] e a g! |

f2 r4 fis | g d g f! | e fis8 g a2 ~ | a4 g a d, |

g4. f8 e2 | d4 r r2 | r r4 b' ~ | b e,_"&c." }

\new Staff \relative b { \clef tenor \key d \minor

r4 bes a8 g a4 | g2 \[ bes^"S3"_"B" | a_"A" c_"C" |

b4._"H" cis8 d2 ~ | d4. cis16 b cis2^\mordent | d r4 dis |

e b e d! | c2 r4 cis4 | d a d c | bes4. a8 g a bes g |

c bes a g fis e fis d | g4 e f! g8 a | bes a g a bes e, a4 ~ |

a d2 c4 | b e2. ~ | e4 r }

\new Staff \relative e { \clef bass \key d \minor

ees4 c d2 | g, r | R1*9 | r2 \[ f'^"A3" | e g |

fis4. gis8 a2 ~ | a4. gis16 fis gis2 | a \] } >>](../../I/25aedd4a6b732550322985ac2c87ae41.png.webp)

This third subject is then treated both by direct motion and by inversion (see bars 213 and 222); and at bar 232 a half close in D minor is made which leads to the final section of the fugue, in which all three subjects are combined. Of this section Bach only lived to write seven bars, which we give exactly as they are found in his autograph.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.BarNumber.break-visibility = ##(#f #t #t) \set Score.barNumberVisibility = #all-bar-numbers-visible \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \set Score.currentBarNumber = #232

\new Staff \relative d'' { \key d \minor \time 4/4 \mark \markup \tiny {(\italic b )} \bar ""

d4. cis8 d e16 f e8 d | cis4 r r8 e^"Free Part." f g |

f e d cis d2 ~ | d4 cis8 d e2 ~ | e4 d8 e f g a f |

d4 e8 fis g a bes g | e4 r r2 | s1 }

\new Staff \relative a' { \key d \minor \clef alto

a8 g f e d4 r | r8 e \[ f^"S2" g f e d cis |

d a d e f e d f | e a, e' f g f16 e f8 g | a g f g a2 ~ |

a8 g16 fis g8 a bes2 ~ | bes8 a g f e d e g | f4 \] s2. }

\new Staff \relative f { \clef tenor \key d \minor

f8 e16 d a'4 ~ a g | a r r2 | R1 | r2 \[ bes^"S3" | a c |

b4. cis8 d2 ~ | d4. cis16 b cis2 | d8 \] e d c b a b d }

\new Staff \relative b, { \clef bass \key d \minor

bes4 a bes2 | a4 r r2 | r \[ d^"S1" | a'2. g4 f1 g a d,4 \] s2. } >>](../../I/db74fb75a43ecf40117cc7374c7d2363.png.webp)

403. A triple fugue, constructed on this plan, will clearly contain four sections, instead of the three with which we are familiar in other fugues; for there will be one for each separate exposition, and a fourth for the final combination of the three subjects. But the length to which the composition will extend will necessarily be so great that this kind of triple fugue is extremely rare. We have met with no other example of it than that which we have been analyzing, though Albrechtsberger mentions a similarly constructed fugue in G minor by Mattheson, from which he quotes a few short passages.

404. In the ordinary triple fugue, the three subjects are announced simultaneously, like the two subjects in the double fugues seen in §§ 370 to 377. But in a four-part fugue, it is evident that the method of exposition in the examples of §§ 370 to 374 will be impossible. After three of the voices have announced the three subjects (which, it must be remembered, should not begin exactly together, though they must all finish together), the fourth voice should enter with the answer to the first subject, two of the other voices giving the other two answers, while the remaining voice may either be silent or add a free part. The three subjects are then heard again, differently distributed between the voices, and then the three answers once more. The exposition is complete as soon as all the subjects have been heard (either as subject or answer) in each of the voices. It is important to remember that the same subject should not be heard twice in succession in the same voice.

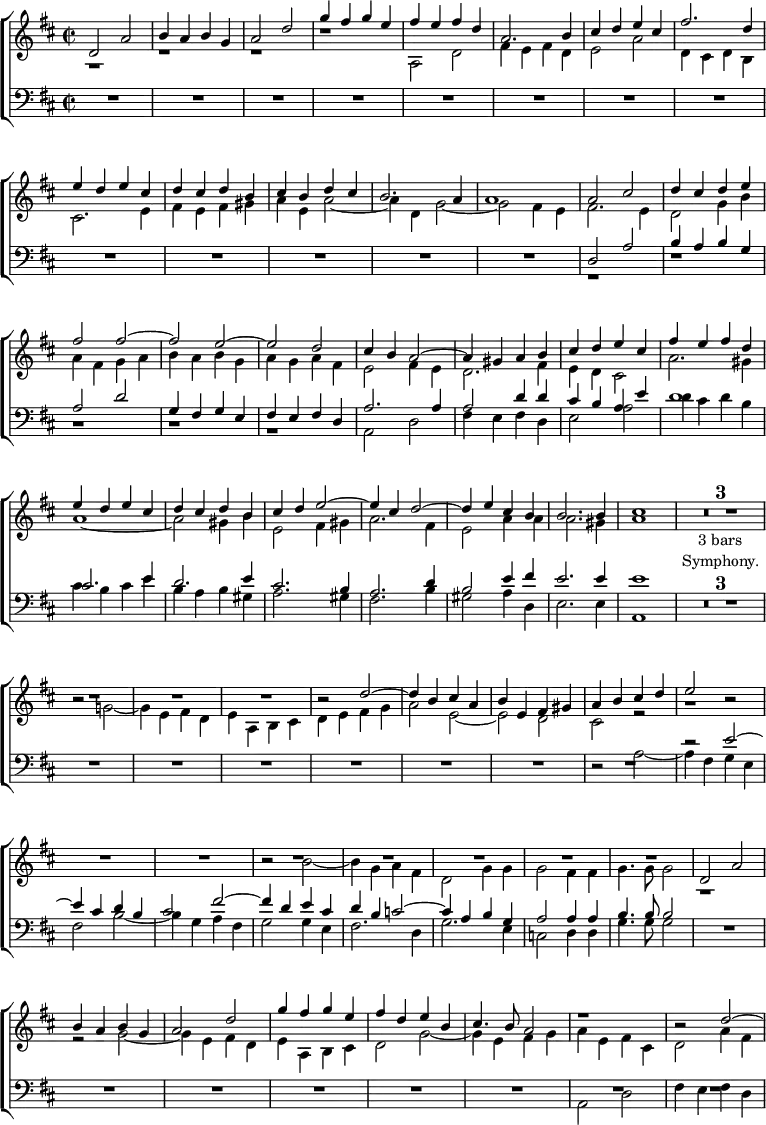

405. The instructions given in the last paragraph will be now illustrated by the exposition of a triple fugue by Albrechtsberger.

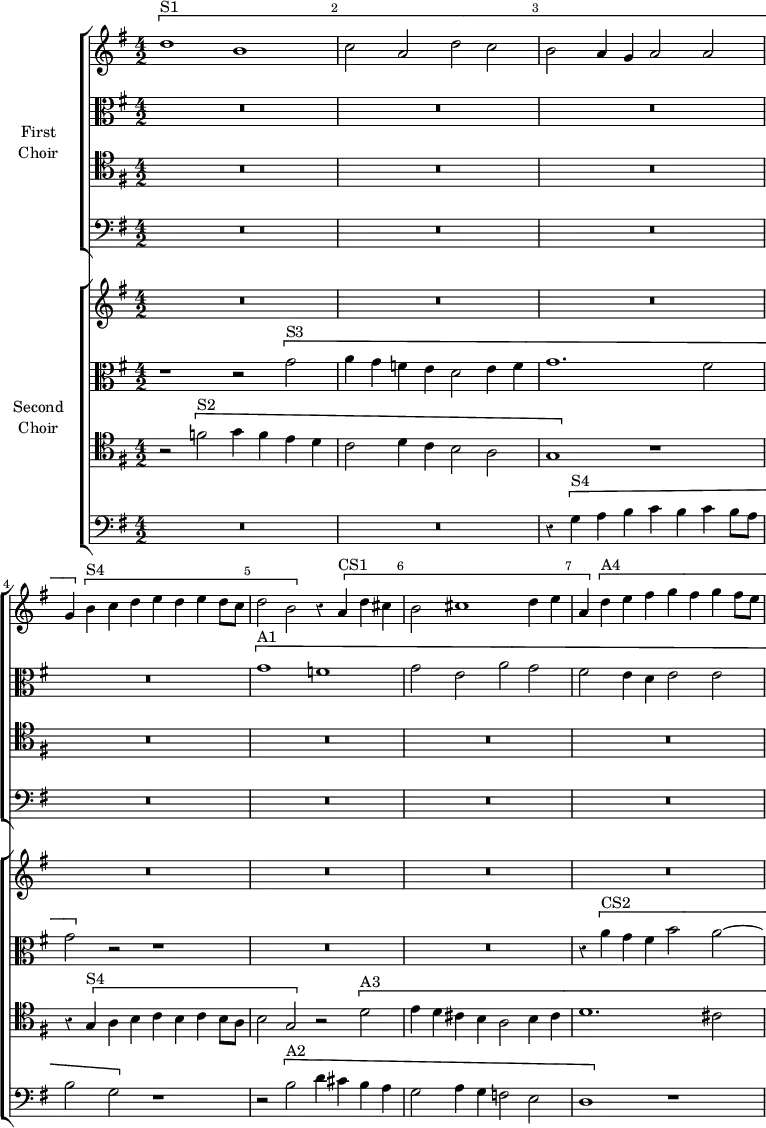

Albrechtsberger.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

\new Staff \relative c'' { \time 2/2

r2 \[ c^"S2" ~ c bes | a d ~ | d c ~ | c b | c1 \] |

r2 r4 \[ g^"A3" | c b c a | b a b g | a1\trill | g4 \] b2 c8 d |

e2 c | R1*4 \[ g2.^"A1" a4 | b c d b | e2. c4 | d2. b4 |

c b8 c d4 c | b2 \] }

\new Staff \relative c' { \clef alto

\[ c2.^"S1" d4 | e f g e | a2. f4 | g2. e4 | f e8 f g4 f |

e2 \] \[ g2^"A2" ~ | a f | e a ~ | a g ~ | g fis |

g4 \] d g f! | e2. f4 | g f e \[ c^"S3" | f e f d | e d e c |

d1\trill | c2 \] b4 c | d c b d | g,2 r | R1*2 | r2_"&c." }

\new Staff \relative g { \clef tenor

R1*5 | \[ g2.^"A1" a4 | b c d b | e2. c4 | d2. b4 |

c4 b8 c d4 c | b \] g2 a8 b | c4 g \[ c2^"S2" ~ c bes |

a d ~ | d c | c b! | c \] g | r r4 \[ g^"A3" | c b c a |

b a b g | a1\trill | g2 \] }

\new Staff \relative c { \clef bass

R1 r2 r4 \[ c^"S3" | f e f d | e d e c | d1\trill | c2 \] e4 f |

g1 | R1*4 \[ c,2.^"S1" d4 | e f g e | a2. f4 | g2. e4 |

f e8 f g4 f | e2 \] \[ g^"A2" ~ | g f | e a ~ | a g ~ g fis g \] } >>](../../I/e46cc31f4062a21c4419019fee901720.png.webp)

It will be seen that each voice has all three subjects in turn, but that none has the same subject twice.

406. The form of this kind of triple fugue is the same ternary form as that of a simple fugue, and the construction of a complete piece of this character will be best shown by the analysis of a fine example from Mozart's Twelfth Mass, a work from which we have already had more than one occasion to quote.

Mozart. Mass in C, No. 12.

The small notes in the bass of bars 14, 21, 25, and 26, and in the treble of bars 34 to 36, are additional parts for the orchestra. We have omitted a few notes for the violins, which merely fill up the harmony, so as to show the fugal construction more clearly; and we have not given the last nine bars of the movement, because these are merely a free coda, and not a part of the fugue itself.

407. The exposition of this fugue extends to the first note of bar 11; it will be seen that each subject has then been heard in all the voices. An additional entry of all the subjects leads to the key of A minor, the last note of the first subject being sharpened in the tenor, to induce the modulation. The middle section of the fugue therefore commences at bar 13, with an episode only one bar in length. At bar 14 is the first group of middle entries, the three subjects appearing in A minor. These are at once followed by incomplete entries of the three answers in E minor, shown, as in our preceding examples, by A—? Fragments of the subjects are then treated sequentially in the second episode (bars 19 to 21), bringing the music to the key of F. In this key the second group of middle entries, incomplete in all the voices, is made at bar 21. The third and last episode (bars 23 to 26) leads back to the key of C, and to the final section of the fugue, which begins in bar 26.

408. This final section contains three groups of entries, all of which are in stretto. In the first and second, the answer enters at a bar and a half's distance after the subject, and all three subjects are present, though, as will be seen, some are incomplete. In the third and closest stretto (bar 34), a part of the first subject is treated by itself in imitation in the octave at one bar's distance in all four voices. It will be seen that at bars 34 to 36, a fragment of the second subject is given by the violins as a counterpoint to the first subject in the voices.

409. It will be noticed that as the subjects modulate to the dominant, they require tonal answers. The subdominant in the second subject prevents the modulation from taking place till the third bar, and we see that all three subjects need modification in the answers. Of the six possible combinations of a triple counterpoint, Mozart has only employed three; but it must be noticed that each of the subjects appears in the bass (Double Counterpoint, § 253). One more point remains to be noticed about this fugue—the almost entire absence of free parts. For the sake, no doubt, of that clearness which is so essential in double and triple fugues, the three subjects always appear without any additions, which might prevent their being easily distinguished. It is not till bar 38 of our extract, and the coda which we have not quoted, that we find any continuous four-part harmony.

410. It is seldom that we find a triple fugue so strictly treated as that by Mozart which we have just been analyzing. Composers usually allow themselves considerable freedom in such cases. For example, the very interesting 'Fuga à 3 soggetti.' in Haydn's quartett in A, Op. 20, No. 6, the three subjects of which are quoted in Double Counterpoint § 262, is, strictly speaking, not a triple fugue at all, but a double fugue, with one regular countersubject; for the third subject appears for the first time as an accompaniment to the answer, and not to the other two subjects, and in some of the middle entries only two of the three subjects are employed together.

411. A Quadruple Fugue, or a fugue on four subjects, is so extremely rare that it will not be needful to say much about it. The four subjects will now evidently have to be written in quadruple counterpoint; but it is very seldom that they will be all announced at once. In Haydn's 'Fuga à 4 soggetti,' in his quartett in C, Op. 20, No. 2, only two of the subjects are announced at first, the third and fourth subjects entering as countersubjects to accompany respectively the first and second appearances of the answers. The four subjects of this fugue, with their various inversions, were quoted as examples of quadruple counterpoint in Double Counterpoint, § 270.

412. In Handel's 'Alexander's Feast,' the final chorus, "Let old Timotheus yield the prize," is sometimes spoken of as a fugue on four subjects. So, in one sense, it is; but it cannot be regarded as a specimen of a true quadruple fugue, because seldom more than two, and never more than three of the four subjects are employed simultaneously. The fugal writing, as is mostly the case with Handel, is far from strict throughout.

413. In Cherubini's 'Counterpoint and Fugue' will be seen a good example of a strict fugue on four subjects, the opening bars of which we gave in § 269 of Double Counterpoint; but probably the finest specimen of a quadruple fugue ever written is the final movement of Cherubini's great 'Credo' for a double choir, which has not only four subjects, but two countersubjects in addition, which make their first appearances against the answers. We have only space to quote the opening bars of this movement.

Cherubini. Credo à 8 voci.

As the last notes of this extract are the commencement of the first episode, we have here the complete exposition of the fugue. With the indications we have given of the entries of the subjects, &c., the student will easily understand it. In a fugue for so many voices and with so many subjects, it is not needful that each subject should be heard in every voice in the course of the exposition. Were it so, the fugue would be protracted to an inordinate length. Let it be also noted that, with so many subjects, the rule that all shall end together is relaxed. Here the second subject ends in the third bar, and the other three not till the fourth. Slight modifications will also be seen in the two countersubjects.

414. In the later developments of such a fugue as this, it is not necessary that all the four subjects should be invariably present together. It will give more variety if sometimes only two or three are treated and developed at once. We advise the student to obtain the score of this 'Credo,' by Cherubini, which is published for a mere trifle in the well-known 'Peters Edition,' and to analyze the whole piece carefully for himself, as we have done the opening bars for him. He will thus probably learn more about the construction of a quadruple fugue than we could tell him in twenty pages of this volume.