CHAPTER IV.

THE ANSWER—CONTINUED.

114. In our last chapter we showed that a tonal answer, though often advisable, was never absolutely necessary for any subject which did not modulate to the key of the dominant. We have now to deal with the treatment of the answer to subjects in which such a modulation occurs.

115. In order to render intelligible the principles on which we shall have to proceed, it is needful here to anticipate somewhat, and to say that in the exposition (§ 11) of a fugue, only two principal keys are employed—mostly tonic and dominant, occasionally tonic and subdominant. In an enormous majority of cases the keys will be tonic and dominant. We saw in the last chapter that if the subject were in the key of the tonic, and remained in it, the answer would be and remain in the key of the dominant. The third voice will almost invariably enter with the subject, and the fourth, if there be four, with the answer. In such cases the answer will generally be real, or if there be any tonal alteration, it will only affect the first two or three notes of the subject.

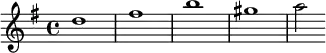

116. But now suppose that instead of ending, as it begins, in the tonic key, the subject modulates to and finishes in the dominant, as in the case given at § 57 (b). It is quite Clear that if we give a real answer in this case, the answer will end in the dominant of the dominant, that is, in the key of the supertonic—

Here we have not only introduced a third principal key, where, as was said in the last paragraph, there ought only to be two; but (what is still more objectionable) we have modulated to an unrelated key (Harmony, § 225). To get back to the tonic key for the entry of the third voice, we shall have to introduce an awkward and probably clumsy join by means of a codetta. In order not to wander away into an unrelated key, and to confine ourselves to the two chief keys already mentioned, which will always be at a distance of a fifth apart, we require a tonal answer here, and adhere to the old rule. This is:—If the subject begin in the tonic, and, modulate to the dominant, the answer must begin in the dominant and modulate to the tonic.

117. This important rule needs to be supplemented by another:—The modulation in the answer from dominant back to tonic must be made at the same point at which the modulation was made in the subject from tonic to dominant. This rule will be fully illustrated as we proceed.

118. The modulation in a fugue subject may be either expressed or implied. It is expressed when the leading note of the dominant key appears as a note of the subject, as in example, §57 (b). It is implied when, although the leading note of the new key is not actually present, the whole form of the melody, and especially its last notes, show more or less distinctly that they are looked at as belonging to the key of the dominant, and when they produce the mental effect of being in that key.

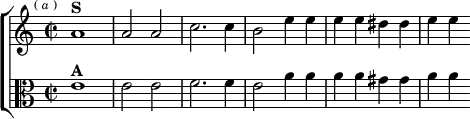

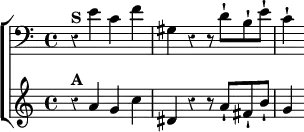

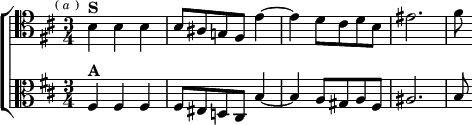

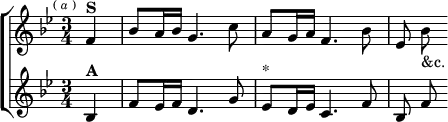

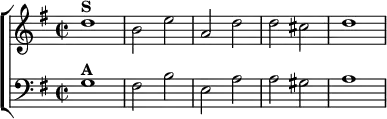

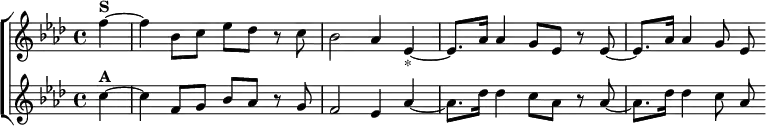

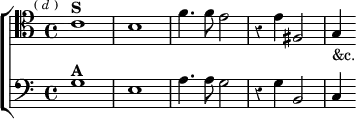

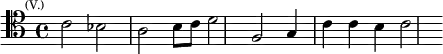

119. The examples now to be given will show what is meant by implied modulation—

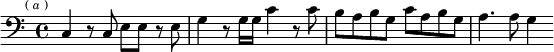

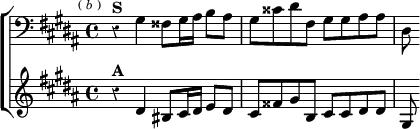

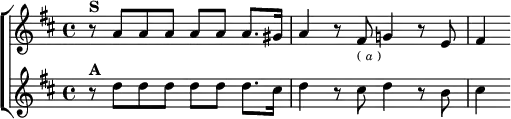

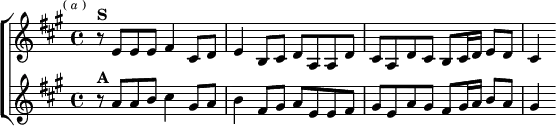

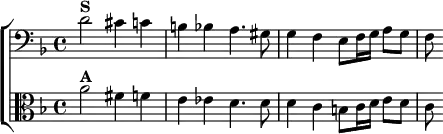

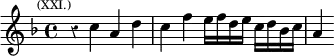

J. S. Bach. Cantata, "Ich hatte viel Bekümmerniss."

J. S. Bach. Cantata, "Gott ist mein König.'

J. S. Bach. Cantata, "Ein' feste Burg."

Handel. 'Saul.'

It will be seen that in all these passages the mental impression of the last notes is unmistakably that of a modulation to the dominant; and it may be stated as a general rule that, whenever a subject ends with the descent from the submediant to the dominant of the tonic key, a modulation is implied, and these two notes are considered to be the supertonic and tonic of the dominant key.

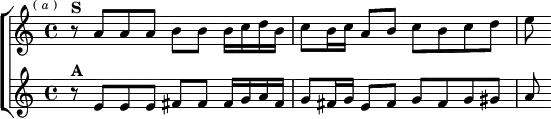

120. Sometimes the great composers choose to consider a modulation as implied when there is no absolute necessity for it—

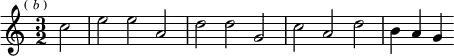

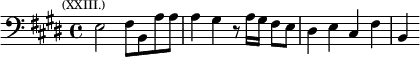

J. S. Bach. Organ Fugue in C.

Here we see from the answer given by Bach that he implies a modulation in the second bar, though a real answer would have been perfectly correct. Had he regarded E as the third of C, he would have answered it by B, the third of G; but he regards it as the sixth of G, and therefore answers it by A, the sixth of C. When a subject modulates to the key of the dominant, all that part which is in the tonic key is transposed in the answer a fifth higher, or a fourth lower; and that part which is in the key of the dominant is transposed a fourth higher, or a fifth lower.

121. The next question is, when there is a modulation, at what point are we to consider it as taking place? The general practice of the great composers is to regard the modulation as being made at the earliest possible point, and from that point to consider every note in its relation to the new key.

122. That the student may quite clearly understand what is meant by this, we will take all the notes in the scale of C major, and show how each can be correctly answered in two ways, according to the point of view from which it is looked at. Supposing our fugue to be in the key of C, and that a modulation to the dominant occurs in the subject, the answer to each note will depend on whether that note comes before or after the modulation:—

C, if regarded as tonic of C, will be answered by G; but if regarded as the subdominant of G, it will be answered by F, the subdominant of C.

D, as the supertonic of C, will be answered by A, the supertonic of G; but D, as the dominant of G, will be answered by G, the dominant of C.

Similarly E, as the third of C is answered by B, the third of G; but if considered as the sixth of G (as in the example in § 120), it will be answered by A, the sixth of C.

F, the subdominant of C, is answered by C; but, as the minor seventh of G, it will be answered by B flat.

G is answered by D when it appears as a dominant, and by C when it is treated as a tonic.

A as a submediant is answered by E, and as a supertonic by D.

B, the leading note of C, is answered by F sharp; but if the context shows it to be the major third of G, it will be answered by E, the major third of C.

123. If the student clearly understands this possible double relation of every note it will save him an infinity of trouble in making a correct tonal answer. We will now analyze a few short examples illustrating the principle just laid down that the modulation should be considered as taking place as early as possible.

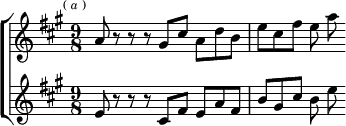

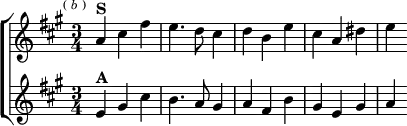

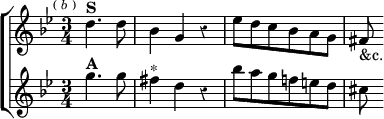

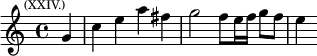

124. As an extremely simple example, we will first take the short passage by Mozart, already quoted in § 57—

Mozart. Quartett in G, No. 14

Here there is in the subject a distinct modulation to D; the answer therefore modulates back to G. B, the second note of the subject, could have been answered either by F sharp or E; but had Mozart answered it by F sharp, the resemblance of answer to subject would have been spoilt—

There would, besides, have been another fault of almost more importance. The subject has a distinct modulation to the dominant; the last three notes unquestionably suggest the key of D. The answer therefore should as clearly suggest G; but in its altered form it does not do so at all, as the first four notes all belong to the tonic chord of D. Neither shall we improve matters by putting B for the third note of the answer instead of A; for then the answer will not distinctly suggest any key at all, the first three notes now being notes of the tonic chord of B minor. There is, therefore, no other correct answer than that which Mozart gives, and, having reached the dominant key at the second note, he regards all the rest of the subject as being in that key, and accordingly treats E as supertonic of D—not as submediant of G—and answers it by A, and not by B. The last two notes of the subject, of course, admit of only one answer.

125. After our full analysis of this example, few words will be needed in explanation of the following, which illustrate the same point—

Handel. 'Israel in Egypt.

J. S. Bach. Matthäus Passion.

At (a) the C in the subject is regarded as sixth of E minor, and answered by F; and at (b) G sharp is considered not as the leading note of A minor, but as the chromatic major third of the dominant, and it is accordingly answered by the major third of the tonic.

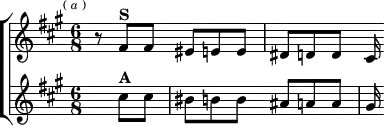

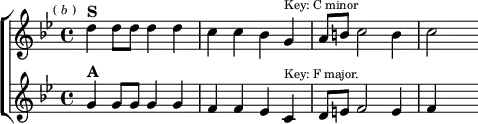

126. The reason why the tonal change is made as early as possible is because in this way a closer general resemblance of the answer to the subject is obtained than if the modulation be regarded as taking place later. Sometimes, however, the form of the subject does not admit of an early change—

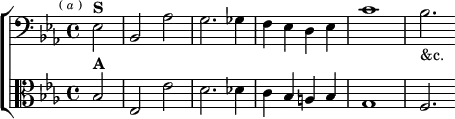

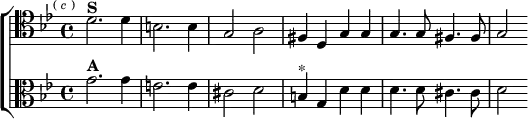

J. S. Bach. Toccata and Fugue for Organ, in C.

The first notes of this subject were spoken of in § 93. It is impossible here to regard the modulation as taking place till after the subdominant harmony at (a). The length and variety of this subject render it a very suitable illustration of the rules we gave in § 122. The student will here see nearly every note of the scale of C in both its relations; we have even at (b) the rare case of the subdominant considered as the minor seventh of the dominant.

127. It is very important to be able to tell when answering a subject that modulates, in which of its two possible aspects any note is to be regarded. The only notes with which any difficulty is likely to be found are the third and the seventh of the tonic, which are also the sixth and third of the dominant. An examination of the fugues of the great masters will guide us in laying down definite rules for the treatment of both these notes.

128. As we have to regard every note in its relation to the new key as early as possible, the third should be considered as the sixth of the dominant, and answered by the sixth of the tonic, as in our examples to §§ 120, 124, and 125 (a), excepting, 1st, when it comes between other notes of the tonic chord, or is followed immediately by the tonic; and 2nd, when the subsequent appearance of the subdominant in the subject shows that the modulation cannot yet have taken place. The following passage shows the third in both aspects—

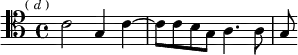

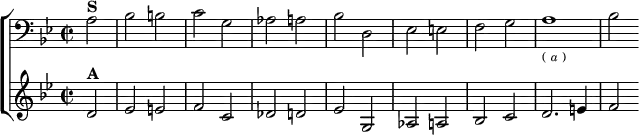

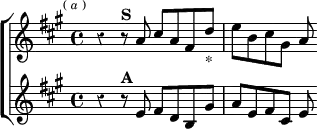

J. S. Bach. Cantata, "Lobe den Herren, den mächtigen König."

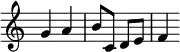

![\new ChoirStaff <<

\new Staff \relative g' { \clef alto \key c \major \time 3/4 \partial 8*5

g16[^\markup \bold "S" f e8] a4 g8 | f16[ e f e f8] d'4 f,16 f |

e8 e16_\markup \tiny { ( \italic a ) } fis g8 a16 b c8 b16 c |

a2. | g4 }

\new Staff \relative b { \clef tenor \key c \major

c8^\markup \bold "A" b e4 d8 | c16[ b c b c8] a'4 c,16 c |

b8 a16 b c8 d16 e f8 e16 f | d2. | c4 } >>](../../I/9af7bdabb92cf8e08482f6cb4ace2af3.png.webp)

The F's in the second bar of the subject prevent our regarding it as in the key of G; but at (a) the change is made at the earliest opportunity. The first E, being the resolution of the F in the preceding bar (the chord being the dominant seventh), must of course be the third of the tonic, and must be answered by B; the: second E is treated as the submediant of G, and answered by the submediant of C—viz., A.

129. We give a few more illustrations of the same point.

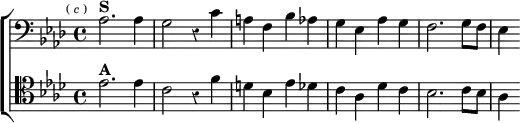

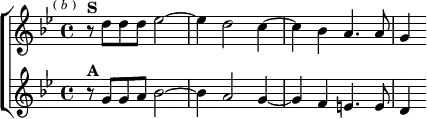

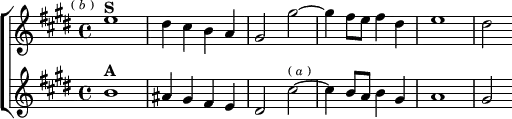

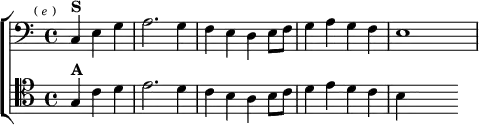

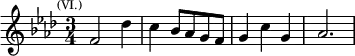

J. S. Bach. Cantata, "Gott ist mein König."

Here the second note of the subject is regarded as the sixth of the dominant, and all the rest is plain sailing.

Mozart. Mass in F, No. 6.

Here the presence of the subdominant prevents our regarding the subject as being in the dominant key till we reach (a), where the third of the scale is treated as sixth of dominant, and answered accordingly. There is an implied modulation (§ 118) in the subject, for it is very rare to find a subject ending on the leading note. It is almost invariably regarded (as here) as the third of the dominant key.

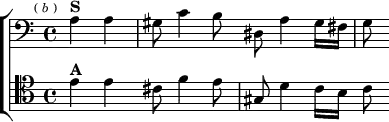

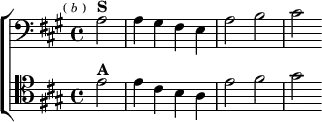

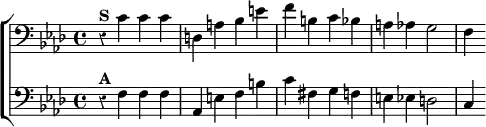

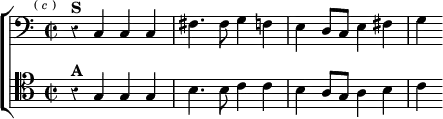

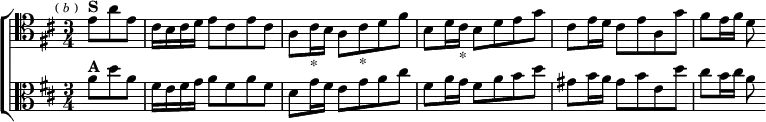

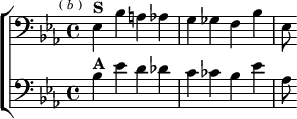

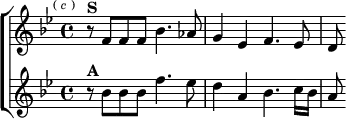

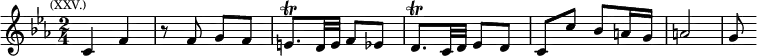

130. In our next example

Handel. Concerto Grosso in C

the change is not made at the earliest possible moment (in the first bar), for this would have disfigured the subject too much.

The mental effect of the music is distinctly that of the key of C, till we come to (a) where the double significance of the third of the scale is very clearly shown. The first E, being followed by C, is the third of the tonic, and is answered by the third of the dominant; the second E is not followed by a note of the tonic chord, and is therefore regarded as sixth of the dominant. Our next example,

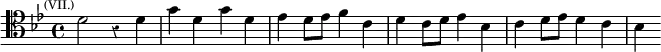

J. S. Bach. Cantata, "Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied."

illustrates a different point. The first F in the third bar cannot be regarded as belonging to the dominant key, because of the G natural that follows, neither can the second which resolves the preceding G; but the F preceding the G sharp is treated as the submediant of A.

131. The same principles will guide us in dealing with the leading note. Let the fundamental principle be thoroughly grasped that the tonal change must be made as soon as possible, and the whole thing is easy. If a subject modulates, the leading note must be always treated as the third of the dominant, and answered by third of tonic, except when it is merely an auxiliary note of the tonic to which it at once returns, e.g.—

J. S. Bach. Wohltemperirtes Clavier, Fugue 2.

This subject does not modulate, but it shows the use of the leading note as an auxiliary note.

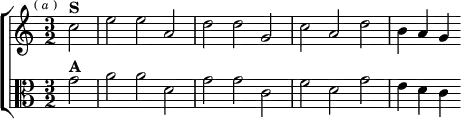

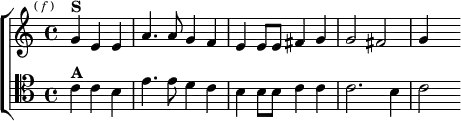

132. The following examples

J. S. Bach. Organ Fugue in C.

J. S. Bach. Wohltemperirtes Clavier, Fugue 18.

Naumann. 1st Mass.

show the leading note very early in the subject treated as the third of the dominant, and answered by third of tonic. The following notes of the subject are all answered as belonging to the dominant key.

133. So strongly is the leading note felt as the third of the dominant that it is not seldom answered by the third of the tonic, even when there is no modulation—

J. S. Bach. Wohltemperirtes Clavier, Fugue 19.

Here Bach treats the second and third notes of his subject as the third and sixth of E, and answers them by third and sixth of A, though the subject ends in the key of the tonic. In our next example

Macfarren. 'The Resurrection.

the second bar is treated as containing a modulation to the key of E, the leading note being answered by the third of the tonic.

134. If the subject begin in the dominant, and modulate to the tonic, the process will be reversed. We shall now, as soon as possible, consider the sixth of the dominant as the third of the tonic, and the third of the dominant as the seventh of the tonic.

Buxtehude.

The first half of this subject is in A; in the second bar it modulates to D; and F, the sixth of A, is therefore at once regarded as the third of the tonic.

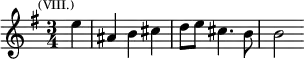

135. Our next example shows the third of the dominant in both its aspects.

Kirnberger.

Let it be noticed that this subject might have been considered as in the key of B flat throughout; it would then have taken a real answer. Kirnberger has preferred to regard it as in F until the last two bars. The tonal change might have been made after the B flat in the fifth bar; but this would have altered the form of the subject needlessly. The point, to illustrate which this passage is quoted, is the treatment of the A in the penultimate bar. It is first regarded as third of dominant, and answered by D, and then looked at as leading note of B flat, and answered by E natural. We saw in § 88 how two notes in the subject were answered by the same note; here is the converse—the same note in the subject has two different notes in the answer.

136. The answering of one note by two is sometimes to be met with in the case of the dominant and supertonic, as in the following passage—

J. S. Bach. Fugue for Clavier, in A.

Here the supertonic at (a) is first answered by the supertonic of E, and then treated as dominant of E, and answered by dominant of A. Evidently had it been so regarded the first time, it would have utterly spoilt the answer.

137. Sometimes the dominant is answered first by tonic and then by supertonic, even when there is no modulation.

Handel. Anthem, "I will magnify thee."

Handel. 'Belshazzar.'

138. If a subject begins in the tonic, modulates to dominant, and returns to tonic, the answer makes the converse modulations—from dominant to tonic, and back to dominant. No new principles are involved here; two examples will be sufficient.

J. S. Bach. Cantata, "Sehet, welch 'eine Liebe."

E. Prout. 2nd Organ Concerto.

139. In general, any leaps of a dissonant interval, such as a seventh, especially of an augmented or diminished interval, should be reproduced exactly in a tonal answer. The student will find illustrations of this in several of the examples already given. At § 93 (c) and § 126 will be seen a diminished fifth; at § 125 (b) a diminished fourth; and at § 132 (b) an augmented fourth, all of which are retained in the answers. We add one example of a diminished seventh—

J. S. Bach. Wohltemperirtes Clavier, Fugue 44.

This subject also contains a diminished fifth which is retained in the answer.

140. There is, however, one important exception to the rule just given. When one of the two notes forming the dissonant interval is the tonic or dominant, and the modulation is made at that point (sometimes even when no modulation is made), a leap of a dissonant interval in the subject will often become a leap of a consonance in the answer, and vice versa. We give some examples—

Kirnberger.

Here both the B and A of the subject are answered by E, on the principle explained in § 88. Our next example shows the reverse case—an octave in the subject becoming a seventh in the answer—

Albrechtsberger.

Here there is an implied modulation, and the change to the dominant key is assumed as early as possible (§ 121). Obviously it cannot be before the third bar at (a). The first G is treated as third of tonic, and the second as sixth of dominant (§ 128).

141. In our example (a) of § 110, we see a seventh in the subject becoming a sixth in the answer. The following interesting passage illustrates both the rule and the exception that we are now discussing—

Kirnberger.

The tonal change at the beginning of the answer alters the seventh into a sixth, but the claims of the tonal answer having been satisfied in the first bar, the augmented and diminished intervals in the second and third bars are exactly imitated.

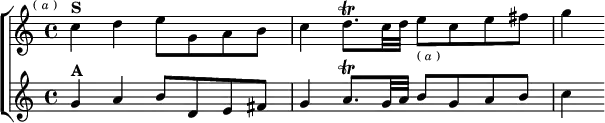

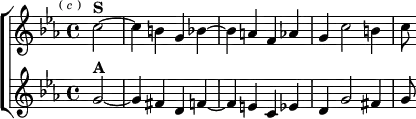

142. In the following passages we see an augmented fourth in the subject becoming a major third in the answer.

J. S. Bach. Cantata, "Ihr werdet weinen und heulen."

Notice that here the augmented second and the minor seventh in the second bar are retained in the answer, and the change of interval comes where the modulation takes place.

Albrechtsberger.

This is a similar instance to the last. The form of the melody renders it impossible to introduce the modulation earlier.

Mozart. Mass in C, No. 4.

This is a curious example, because Mozart by the way he answers the subject implies three modulations—to the dominant and back in bar 2, and again to the dominant at the end. It would have been simpler to treat the first F sharp, which is almost immediately contradicted, as a chromatic note, and to have given the answer the following form—

which would have been equally correct here (compare § 65).

143. Our next example shows the converse case, a major third in the subject becoming an augmented fourth in the answer.

Albrechtsberger.

This passage illustrates the partiality of fugue writers for treating the third of the tonic as the sixth of the dominant, and the leading note as the third of the dominant. There is no necessity for a tonal change till (a), and the answer might have been

Here we have another example of what we haye already seen more than once, that it is sometimes possible for a subject to have two different answers, both correct. The student will learn by experience, in such cases, which is the better.

144. Though, as a general rule, the transposition of the subject a perfect fourth or fifth should be strictly carried out, we often find the position of the semitones disregarded, a semitone being answered by a tone, and a tone by a semitone. This is especially the case with the subdominant and leading note, as will be seen by the following passages, selected from a much larger number we had marked for quotation—

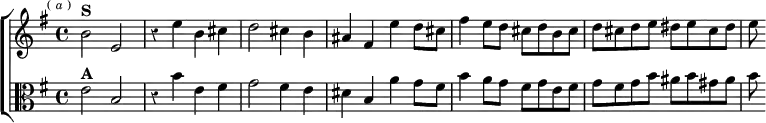

J. S. Bach. Fughetta on "Allein Gott in der Höh' sei Ehr'."

J. S. Bach. Mass in B minor.

Mozart. Litany in B flat.

145. On the same principle—the disregard of semitones—must be explained the occasional answering of a major by a minor third, or a minor by a major, in the course of a subject. This must not be confounded with the regularly allowed substitution of a major for a minor third, at the end of a subject, spoken of in § 69.

J. S. Bach. Organ Fugue in B flat.

Handel. 'Muzio Scevola.'

P. Winter. 'Stabat Mater.

In all the above passages the alterations in the answer are marked with an asterisk. Students are advised not to imitate such freedoms as these, but in all cases to preserve the position of the semitones, except, of course, at the moment of modulation.

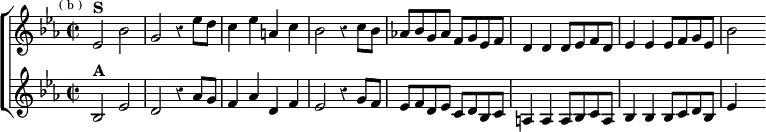

146. Before leaving the subject of tonal answers, it must be added that we occasionally (we might also say exceptionally) find the dominant key answered by the supertonic, instead of by the tonic. Sometimes this is in an incidental modulation, as in the following passage—

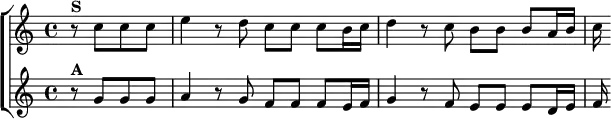

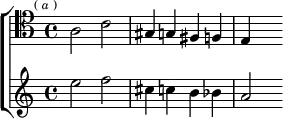

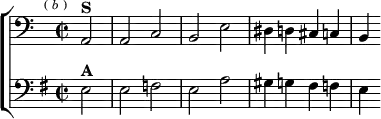

Handel. Dettingen Anthem.

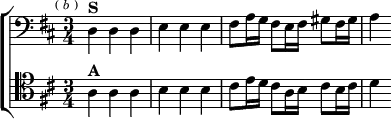

![\new ChoirStaff <<

\new Staff \relative a' { \clef alto \key d \major \time 4/4 \partial 2

r8^\markup \bold "S" a a a |\[ b4 fis8_"N.B." gis a4 \] r8 d, |

cis a g'! a16 g fis8 d_"&c." }

\new Staff \relative d'' { \key d \major

r8^\markup \bold "A" d d d |\[ fis4 cis8 dis e4 \] r8 a, |

gis e d' e16 d cis8 a } >>](../../I/bc37668be0992cdc10a6d4822f5570b1.png.webp)

Here the answer at the "N.B." is, to say the least of it, unusual. The subject appears to commence in the dominant, and to modulate into the tonic; and the regular answer would certainly have been

147. Sometimes, though very seldom, we find a final modulation to the dominant answered by one to the supertonic, as in the example (f) of § 107, where, however, Mendelssohn harmonizes the last notes of the answer in F minor, instead of F major, so as not to leave the circle of nearly related keys. In the following passage there is a distinct modulation to A major in the answer—

Leo. "Dixit Dominus."

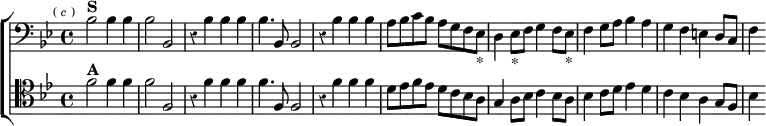

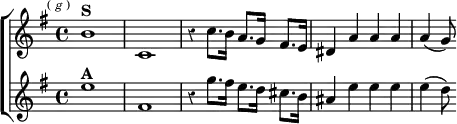

148. Our last illustration of this point is instructive.

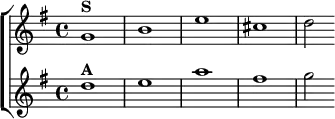

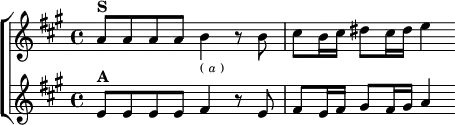

J. S. Bach. Wohltemperirtes Clavier, Fugue 10.

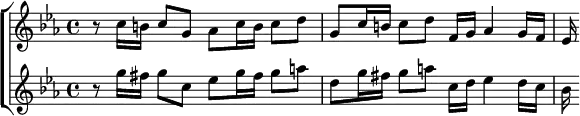

![\new ChoirStaff <<

\new Staff \relative e' { \key e \minor \time 3/4

e16^\markup \bold "S" g b e dis e d e cis e c e |

b e dis e ais, cis g fis g ais fis e | d8[ b'] }

\new Staff \relative b, { \clef bass \key e \minor

b16^\markup \bold "A" d fis b ais b a b gis b g b |

fis b ais b eis, gis d cis d eis cis b | ais8[ fis'] } >>](../../I/bb2dc2c470189b30652158d2d43a28cd.png.webp)

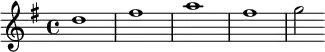

Notice, in passing, the minor third at the end of the subject answered by a major third (§ 69). We see here the only example in all Bach's works of a real answer given to a subject that closes in the key of the dominant; but here it can be not only explained but justified. We have already spoken (§ 139) of the importance of retaining augmented and diminished intervals as far as possible in the answer. Had Bach given a tonal answer here,

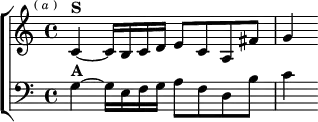

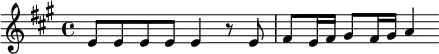

![\relative b, { \time 3/4 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \clef bass

b16 d fis b ais b a b gis b g b | fis b ais b dis, fis c b c dis b a | g8[ e'] }](../../I/8be9e61774cf61766eb7a1454c90d4a1.png.webp)

he would have had to sacrifice the diminished fifth in the second bar, and the harmonic framework of the bar would have been entirely changed. But there is a further reason here. We said, in § 116, that a tonal answer was required when the subject modulated to the dominant, in order to get back to the tonic for the entry of the third voice. But the fugue we are now discussing is for two parts only; and after the first entry of the answer, the exposition (§ 11) is complete, and we reach the first episode, where, as we shall see later, modulation usually begins. There is, therefore, here no occasion to return to the tonic key. The same reason may probably explain the putting the second answer into the key of the subdominant, noticed in § 111. Students should always keep to the regular rule, and answer a subject modulating to the dominant by a return to the tonic.

149. Chromatic subjects usually take real answers, unless there be a modulation expressed or implied.

J. S. Bach. Toccata in F sharp minor.

J. S. Bach. Fugue for Clavier, in E flat.

Mozart. Mass in C minor.

At (b) the leap of a fifth is answered tonally, but the chromatic passage itself is exactly repeated. The answer is in the subdominant (§ 71.) At (c) other notes occur between the chromatic notes.

150. Sometimes a composer has chosen to consider a modulation implied where there is no real necessity for it.

Mozart. Quartett in D minor, No. 13.

Here a real answer, as at § 149 (a), would have been much more usual, and (with all respect to Mozart, be it said) much better. The threefold repetition of D spoils the form of the answer.

151. If there be a modulation before the chromatic notes are introduced, such notes must be considered as belonging to the new key, and answered accordingly—

Handel. 'Jephtha.

Kirnberger.

152. Fugue subjects are sometimes answered by inversion. In this case the answer is not generally in the key of the dominant; but that species of inversion is used in which dominant is answered by tonic, and tonic by dominant (Double Counterpoint, §§ 281, 282). Sometimes the answer by inversion is given in the first exposition, as in Bach's 'Art of Fugue,' No. 5—

J. S. Bach. Art of Fugue, No. 5.

More frequently, however, this device is reserved for the later developments of the fugue, in order to heighten the interest, as in Nos. 15, 20, and 46, of the 'Wohltemperirtes Clavier.' An answer by inversion is much more common with a minor subject than with a major.

153. We also sometimes find answers by augmentation and diminution. In these again there is no need that the answer should be in the dominant key. The object of putting the answer in the dominant is to prevent its being a mere monotonous repetition of the subject; and this end is sufficiently attained either by inversion or by altering the lengths of the notes. In Nos. 6 and 7 of the 'Art of Fugue' will be seen examples, too long to quote here, of answers by augmentation and diminution.

154. Sometimes, especially in vocal fugues, in order to keep the answer in a more convenient compass, the change of an octave in pitch is made in the course of the answer, as in the following passage—

Schumann. Requiem.

A similar example, which is familiar to everybody, will be found in the "Amen" chorus of the 'Messiah.'

155. It is often said that there are no rules without exceptions; and in the works of all the great masters we occasionally find fugue answers which cannot be explained on any of the principles laid down in this chapter. As our last illustrations, we give one specimen by each of the greatest composers, of an irregular fugue answer. If the student has mastered the contents of this chapter, no notes will be needed; he will see at once wherein the irregularity consists.

J. S. Bach. Fugue for Clavier, in A minor.

Handel. 'Choice of Hercules.'

Haydn. 'Creation.

Mozart. Te Deum.

Beethoven. Mass in C.

Weber. Mass in E flat.

Mendelssohn. Fugue in E minor.

Schumann. Fugue, Op. 72, No. 2.

The only remarks required by these examples are that (b) has an independent orchestral accompaniment, the harmony clearly proving—what does not appear from the quotation itself—that the subject ends in C minor, and the answer in F major; and that (h) may possibly be considered an extreme instance of the disregard of semitones spoken of in §§ 144, 145.

156. We have now arrived at the end of a very long and difficult task—that of explaining the principles of fugal answer. The rules here given differ widely in some respects from those generally laid down; but not one new rule has been advanced which we have not justified by the example of the greatest composers. We shall now, by way of summary, endeavour to put the general principles into the fewest possible words.

I. The answer to a subject which is in the key of the tonic should be as a rule in the key of the dominant; but if dominant harmony is prominent in the subject, the answer may occasionally be in the subdominant.

II. A real answer is possible for any subject which begins and ends in the key of the tonic without modulating to the dominant; but if the subject begins with a leap between tonic and dominant or commences on the dominant, a tonal answer is mostly preferable.

III. If the subject modulate between the keys of the tonic and dominant, the answer should make the converse modulations between dominant and tonic.

IV. A modulation should always be made as early as possible. In a modulation from tonic to dominant consider the third and seventh of the tonic as sixth and third of dominant as soon as the modulation can be considered as having taken place, and answer them accordingly.

157. These few sentences embody all the fundamental principles of a fugal answer; the less important details have been dealt with in this and the preceding chapter. The student who has thoroughly understood the rules here given will have but little difficulty in answering any fugue subject that may be set him, unless (as is sometimes the case in examinations) a bad and unsuitable subject is given as a "catch." In such cases, he must trust to his luck; we have seen subjects in examination papers to which a good answer was absolutely impossible.

158. We conclude this chapter with giving a number of fugue subjects, original and selected, for the student to answer. We also, as a useful exercise, give a few answers to which he is to find the subjects. This will of course be the converse process. If the answer ends in the key of the tonic, the subject must have ended in the key of the dominant, and vice versa; if the answer begins with the dominant, the subject most probably began with the tonic. First ascertain in what key the answer ends, and if there has been a modulation, make that modulation as early as possible in the subject. The rules for the treatment of the third and seventh of the tonic (§§ 128–133) will be of considerable assistance in this matter.

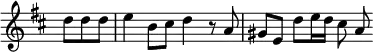

Exercises.

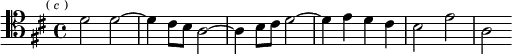

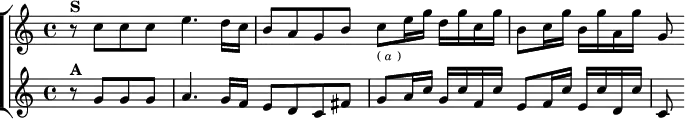

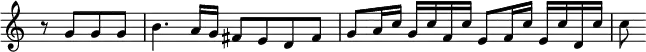

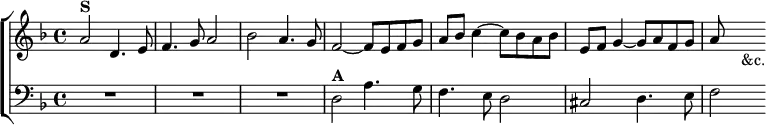

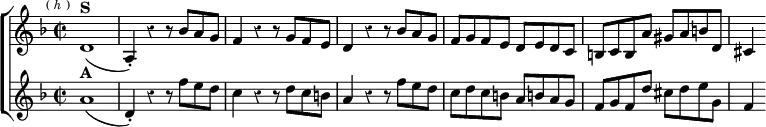

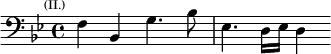

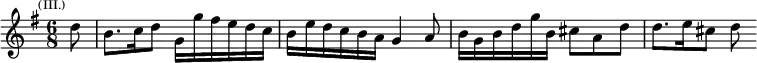

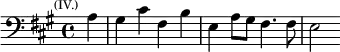

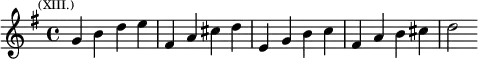

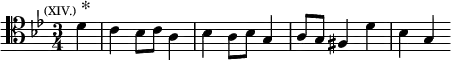

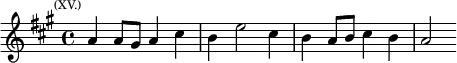

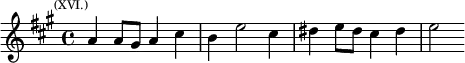

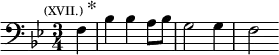

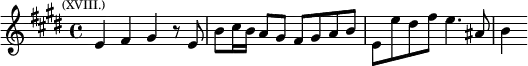

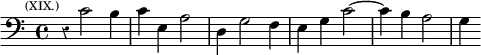

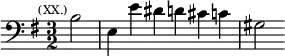

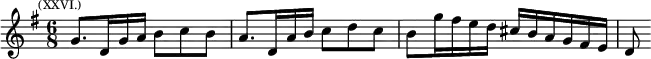

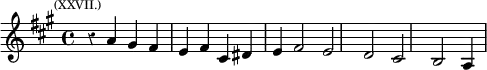

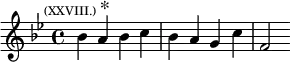

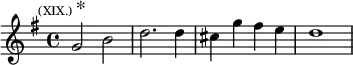

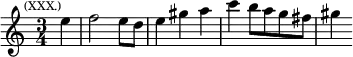

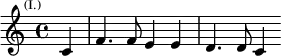

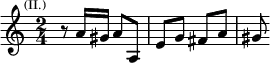

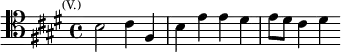

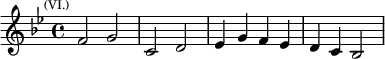

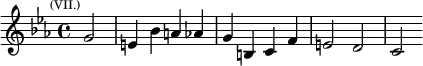

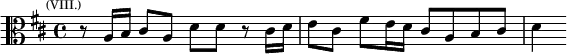

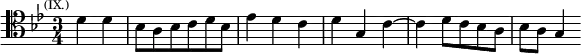

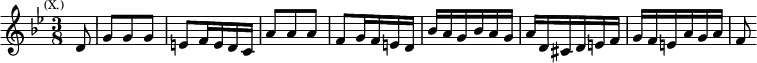

(1.) Find the answers to the following subjects—

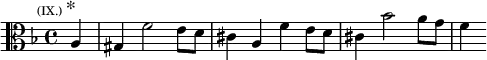

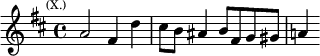

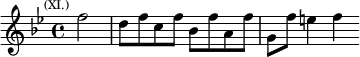

* Subjects marked with an asterisk can have more than one correct answer.

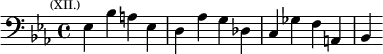

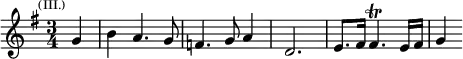

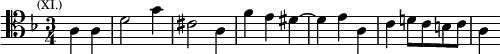

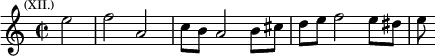

(2.) Find the subjects of which the following are the answers—

Note.—The greater part of these answers are taken from fugues by Bach. All the more elaborate and difficult ones are from his works; and the trouble involved in finding the proper subjects will be well repaid.