SERPENT (Lat. serpens, creeping, from serpere; cf. “reptile” from repere, Gr. ἕρπειν), a synonym for reptile or snake (see Reptile, and Snakes), now generally used only of dangerous varieties, or metaphorically. See also Serpent-Worship below.

In music the serpent (Fr. serpent, Ger. Serpent, Schlangenrohr,

Ital. serpentone) is an obsolete bass wind instrument derived from

the old wooden cornets (Zinken), and the progenitor of the

bass-horn, Russian bassoon and ophicleide. The serpent is

composed of two pieces of wood, hollowed out and cut to the

desired shape. They are so joined together by gluing as to form

a conical tube of wide calibre with a diameter varying from a

little over half an inch at the crook to nearly 4 in. at the wider end.

The tube is covered with leather to ensure solidity. The upper

extremity ends with a bent brass tube or crook, to which the

cup-shaped mouthpiece is attached; the lower end does not expand

to form a bell, a peculiarity the serpent shared with the cornets.

The tube is pierced laterally with six holes, the first three of

which are covered with the fingers of the right hand and the

others with those of the left. When all the holes are thus

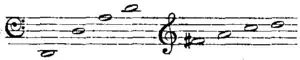

closed the instrument will produce the following sounds, of

which the first is the fundamental and the rest the harmonic

series founded thereon:  Each

of the holes on being successively opened gives the same

series of harmonics on a new fundamental, thus producing a

chromatic compass of three octaves by means of six holes only.

The holes are curiously disposed along the

tube for convenience in reaching them

with the fingers; in consequence they are

of very small diameter, and this affects the

intonation and timbre of the instrument

adversely. With the application of keys

to the serpent, which made it possible

to place the holes approximately in the

correct theoretical position, whereby the

diameter of the holes was also made

proportional to that of the tube, this defect

was remedied and the timbre improved.

Each

of the holes on being successively opened gives the same

series of harmonics on a new fundamental, thus producing a

chromatic compass of three octaves by means of six holes only.

The holes are curiously disposed along the

tube for convenience in reaching them

with the fingers; in consequence they are

of very small diameter, and this affects the

intonation and timbre of the instrument

adversely. With the application of keys

to the serpent, which made it possible

to place the holes approximately in the

correct theoretical position, whereby the

diameter of the holes was also made

proportional to that of the tube, this defect

was remedied and the timbre improved.

The serpent was, according to Abbé Lebœuf,[1] the outcome of experiments made on the cornon, the bass cornet or Zinke, by Edmé Guillaume, canon of Auxerre, in 1590. The invention at once proved a success, and the new bass became a valuable addition to church concerted music, more especially in France, in spite of the serpent's harsh, unpleasant tone. Mersenne (1636) describes and figures the serpent of his day in detail, but it was evidently unknown to Praetorius (1618). During the 18th century the construction of the instrument underwent many improvements, the tendency being to make the unwieldy windings more compact. At the beginning of the 19th century the open holes had been discarded, and as many as fourteen or seventeen keys disposed conveniently along the tube. Gerber, in his Lexikon (1790), states that in 1780 a musician of Lille, named Régibo, making further experiments on the serpent, produced a bass horn, giving it the shape of the bassoon for greater portability; and Frichot, a French refugee in London, introduced a variant of brass which rapidly won favour under the name of “bass horn” or “basson russe” in English military bands. On being introduced on the continent of Europe, this instrument was received into general use and gave a fresh impetus to experiments with basses for military bands, which resulted first in the ophicleide (q.v.) and ultimately in the valuable invention of the piston or valve.

Further information as to the technique and construction of the serpent may be gained from Joseph Fröhlich's excellent treatise on all the instruments of the orchestra in his day (Bonn, 1811), where clear and accurate practical drawings of the instruments are given.

(K. S.)

- ↑ See Mémoire concernant l'histoire ecclésiastique et civile d'Auxerre (Paris. 1848), ii. 189.