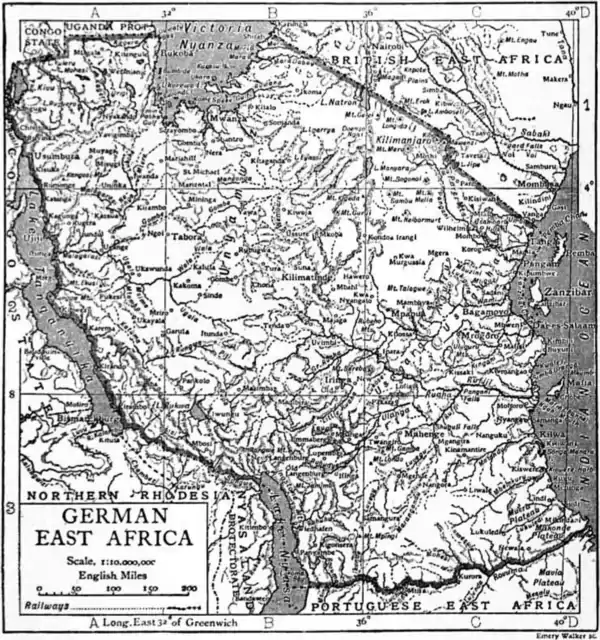

GERMAN EAST AFRICA, a country occupying the east-central portion of the African continent. The colony extends at its greatest length north to south from 1° to 11° S., and west to east from 30° to 40° E. It is bounded E. by the Indian Ocean (the coast-line extending from 4° 20′ to 10° 40′ S.), N.E. and N. by British East Africa and Uganda, W. by Belgian Congo, S.W. by British Central Africa and S. by Portuguese East Africa.

- Sections

- I.—Map

- II.—Topography

- Area and Boundaries • Physical Features • Geology • Climate • Flora & Fauna

- III.—Inhabitants

- IV.—History

- V.—Authorities

Area and Boundaries.—On the north the boundary line runs N.W. from the mouth of the Umba river to Lake Jipe and Mount Kilimanjaro including both in the protectorate, and thence to Victoria Nyanza, crossing it at 1° S., which parallel it follows till it reaches 30° E. In the west the frontier is as follows: From the point of intersection of 1° S. and 30° E., a line running S. and S.W. to the north-west end of Lake Kivu, thence across that lake near its western shore, and along the river Rusizi, which issues from it, to the spot where the Rusizi enters the north end of Lake Tanganyika; along the middle line of Tanganyika to near its southern end, when it is deflected eastward to the point where the river Kalambo enters the lake (thus leaving the southern end of Tanganyika to Great Britain). From this point the frontier runs S.E. across the plateau between Lakes Tanganyika and Nyasa, in its southern section following the course of the river Songwe. Thence it goes down the middle of Nyasa as far as 11° 30′ S. The southern frontier goes direct from the last-named point eastward to the Rovuma river, which separates German and Portuguese territory. A little before the Indian Ocean is reached the frontier is deflected south so as to leave the mouth of the Rovuma in German East Africa. These boundaries include an area of about 364,000 sq. m. (nearly double the size of Germany), with a population estimated in 1910 at 8,000,000. Of these above 10,000 were Arabs, Indians, Syrians and Goanese, and 3000 Europeans (over 2000 being Germans). The island of Mafia (see below) is included in the protectorate.

Physical Features.—The coast of German East Africa (often spoken of as the Swahili coast, after the inhabitants of the seaboard) is chiefly composed of coral, is little indented, and is generally low, partly sandy, partly rich alluvial soil covered with dense bush or mangroves. Where the Arabs have established settlements the coco-palm and mango tree introduced by them give variety to the vegetation. The coast plain is from 10 to 30 m. wide and 620 m. long; it is bordered on the west by the precipitous eastern side of the interior plateau of Central Africa. This plateau, considerably tilted from its horizontal position, attains its highest elevation north of Lake Nyasa (see Livingstone Mountains), where several peaks rise over 7000 ft., one to 9600, while its mean altitude is about 3000 to 4000 ft. From this region the country slopes towards the north-west, and is not distinguished by any considerable mountain ranges. A deep narrow gorge, the so-called “eastern rift-valley,” traverses the middle of the plateau in a meridional direction. In the northern part of the country it spreads into several side valleys, from one of which rises the extinct volcano Kilimanjaro (q.v.), the highest mountain in Africa (19,321 ft.). Its glaciers send down a thousand rills which combine to form the Pangani river. About 40 m. west of Kilimanjaro is Mount Meru (14,955 ft.), another volcanic peak, with a double crater. The greater steepness of its sides makes Meru in some aspects a more striking object than its taller neighbour. South-east of Mount Kilimanjaro are the Pare Mountains and Usambara highlands, separated from the coast by a comparatively narrow strip of plain. To the south of the Usambara hills, and on the eastern edge of the plateau, are the mountainous regions of Nguru (otherwise Unguru), Useguha and Usagara. As already indicated, the southern half of Victoria Nyanza and the eastern shores, in whole or in part, of Lakes Kivu, Tanganyika and Nyasa, are in German territory. (The lakes are separately described.) Several smaller lakes occur in parts of the eastern rift-valley. Lake Rukwa (q.v.) north-west of Nyasa is presumably only the remnant of a much larger lake. Its extent varies with the rainfall of each year. North-west of Kilimanjaro is a sheet of water known as the Natron Lake from the mineral alkali it contains. In the northern part of the colony the Victoria Nyanza is the dominant physical feature. The western frontier coincides with part of the eastern wall of another depression, the Central African or Albertine rift-valley, in which lie Tanganyika, Kivu and other lakes. Along the north-west frontier north of Kivu are volcanic peaks (see Mfumbiro).

The country is well watered, but with the exception of the Rufiji the rivers, save for a few miles from their mouths, are unnavigable. The largest streams are the Rovuma and Rufiji (q.v.), both rising in the central plateau and flowing to the Indian Ocean. Next in importance is the Pangani river, which, as stated above, has its head springs on the slopes of Kilimanjaro. Flowing in a south-easterly direction it reaches the sea after a course of some 250 m. The Wami and Kingani, smaller streams, have their origin in the mountainous region fringing the central plateau, and reach the ocean opposite the island of Zanzibar. Of inland river systems there are four—one draining to Victoria Nyanza, another to Tanganyika, a third to Nyasa and a fourth to Rukwa. Into Victoria Nyanza are emptied, on the east, the waters of the Mori and many smaller streams; on the west, the Kagera (q.v.), besides smaller rivers. Into Tanganyika flows the Malagarasi, a considerable river with many affluents, draining the west-central part of the plateau. The Kalambo river, a comparatively small stream near the southern end of Tanganyika, flows in a south-westerly direction. Not far from its mouth there is a magnificent fall, a large volume of water falling 600 ft. sheer over a rocky ledge of horse-shoe shape. Of the streams entering Nyasa the Songwe has been mentioned. The Ruhuhu, which enters Nyasa in 10° 30′ S., and its tributaries drain a considerable area west of 36° E. The chief feeders of Lake Rukwa are the Saisi and the Rupa-Songwe.

Mafia Island lies off the coast immediately north of 8° N. It has an area of 200 sq. m. The island is low and fertile, and extensively planted with coco-nut palms. It is continued southwards by an extensive reef, on which stands the chief village, Chobe, the residence of a few Arabs and Banyan traders. Chobe stands on a shallow creek almost inaccessible to shipping.

Geology.—The narrow foot-plateau of British East Africa broadens out to the south of Bagamoyo to a width of over 100 m. This is covered to a considerable extent by rocks of recent and late Tertiary ages. Older Tertiary rocks form the bluffs of Lindi. Cretaceous marls and limestones appear at intervals, extending in places to the edge of the upper plateau, and are extensively developed on the Makonde plateau. They are underlain by Jurassic rocks, from beneath which sandstones and shales yielding Glossopteris browniana var. indica, and therefore of Lower Karroo age, appear in the south but are overlapped on the north by Jurassic strata. The central plateau consists almost entirely of metamorphic rocks with extensive tracts of granite in Unyamwezi. In the vicinity of Lakes Nyasa and Tanganyika, sandstones and shales of Lower Karroo age and yielding seams of coal are considered to owe their position and preservation to being let down by rift faults into hollows of the crystalline rocks. In Karagwe certain quartzites, slates and schistose sandstones resemble the ancient gold-bearing rocks of South Africa.

The volcanic plateau of British East Africa extends over the boundary in the region of Kilimanjaro. Of the sister peaks, Kibo and Mawenzi, the latter is far the oldest and has been greatly denuded, while Kibo retains its crateriform shape intact. The rift-valley faults continue down the depression, marked by numerous volcanoes, in the region of the Natron Lake and Lake Manyara; while the steep walls of the deep depression of Tanganyika and Nyasa represent the western rift system at its maximum development.

Fossil remains of saurians of gigantic size have been found; one thigh bone measures 6 ft. 10 in., the same bone in the Diplodocus Carnegii measuring only 4 ft. 11 in.

Climate.—The warm currents setting landwards from the Indian Ocean bring both moisture and heat, so that the Swahili coast has a higher temperature and heavier rainfall than the Atlantic seaboard under the same parallels of latitude. The mean temperature on the west and east coasts of Africa is 72° and 80° Fahr. respectively, the average rainfall in Angola 36 in., in Dar-es-Salaam 60 in. On the Swahili coast the south-east monsoon begins in April and the north-east monsoon in November. In the interior April brings south-east winds, which continue until about the beginning of October. During the rest of the year changing winds prevail. These winds are charged with moisture, which they part with on ascending the precipitous side of the plateau. Rain comes with the south-east monsoon, and on the northern part of the coast the rainy season is divided into two parts, the great and the little Masika: the former falls in the months of September, October, November; the latter in February and March. In the interior the climate has a more continental character, and is subject to considerable changes of temperature; the rainy season sets in a little earlier the farther west and north the region, and is well marked, the rain beginning in November and ending in April; the rest of the year is dry. On the highest parts of the plateau the climate is almost European, the nights being sometimes exceedingly cold. Kilimanjaro has a climate of its own; the west and south sides of the mountain receive the greatest rainfall, while the east and north sides are dry nearly all the year. Malarial diseases are rather frequent, more so on the coast than farther inland. The Kilimanjaro region is said to enjoy immunity. Smallpox is frequent on the coast, but is diminishing before vaccination; other epidemic diseases are extremely rare.

Flora and Fauna.—The character of the vegetation varies with and depends on moisture, temperature and soil. On the low littoral zone the coast produced a rich tropical bush, in which the mangrove is very prominent. Coco-palms and mango trees have been planted in great numbers, and also many varieties of bananas. The bush is grouped in copses on meadows, which produce a coarse tall grass. The river banks are lined with belts of dense forest, in which useful timber occurs. The Hyphaene palm is frequent, as well as various kinds of gum-producing mimosas. The slopes of the plateau which face the rain-bringing monsoon are in some places covered with primeval forest, in which timber is plentiful. The silk-cotton tree (Bombax ceiba), miomba, tamarisk, copal tree (Hymenaea courbaril) are frequent, besides sycamores, banyan trees (Ficus indica) and the deleb palm (Borassus aethiopum). It is here we find the Landolphia florida, which yields the best rubber. The plateau is partly grass land without bush and forest, partly steppe covered with mimosa bush, which sometimes is almost impenetrable. Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Meru exhibit on a vertical scale the various forms of vegetation which characterize East Africa (see Kilimanjaro).

East Africa is rich in all kinds of antelope, and the elephant, rhinoceros and hippopotamus are still plentiful in parts. Characteristic are the giraffe, the chimpanzee and the ostrich. Buffaloes and zebras occur in two or three varieties. Lions and leopards are found throughout the country. Crocodiles are numerous in all the larger rivers. Snakes, many venomous, abound. Of birds there are comparatively few on the steppe, but by rivers, lakes and swamps they are found in thousands. Locusts occasion much damage, and ants of various kinds are often a plague. The tsetse fly (Glossina morsitans) infests several districts; the sand-flea has been imported from the west coast. Land and water turtles are numerous.

Inhabitants.—On the coast and at the chief settlements inland are Arab and Indian immigrants, who are merchants and agriculturists. The Swahili (q.v.) are a mixed Bantu and Semitic race inhabiting the seaboard. The inhabitants of the interior may be divided into two classes, those namely of Bantu and those of Hamitic stock. What may be called the indigenous population consists of the older Bantu races. These tribes have been subject to the intrusion from the south of more recent Bantu folk, such as the Yao, belonging to the Ama-Zulu branch of the race, while from the north there has been an immigration of Hamito-Negroid peoples. Of these the Masai and Wakuafi are found in the region between Victoria Nyanza and Kilimanjaro. The Masai (q.v.) and allied tribes are nomads and cattle raisers. They are warlike, and live in square mud-plastered houses called tembe which can be easily fortified and defended. The Bantu tribes are in general peaceful agriculturists, though the Bantus of recent immigration retain the warlike instincts of the Zulus. The most important group of the Bantus is the Wanyamwezi (see Unyamwezi), divided into many tribes. They are spread over the central plains, and have for neighbours on the south-east, between Nyasa and the Rufiji, the warlike Wahehe. The Wangoni (Angoni), a branch of the Ama-Zulu, are widely spread over the central and Nyasa regions. Other well-known tribes are the Wasambara, who have given their name to the highlands between Kilimanjaro and the coast, and the Warundi, inhabiting the district between Tanganyika and the Kagera. In Karagwe, a region adjoining the south-west shores of Victoria Nyanza, the Bahima are the ruling caste. Formerly Karagwe under its Bahima kings was a powerful state. Many different dialects are spoken by the Bantu tribes, Swahili being the most widely known (see Bantu Languages). Their religion is the worship of spirits, ancestral and otherwise, accompanied by a vague and undefined belief in a Supreme Being, generally regarded as indifferent to the doings of the people.

The task of civilizing the natives is undertaken in various ways by the numerous Protestant and Roman Catholic missions established in the colony, and by the government. The slave trade has been abolished, and though domestic slavery is allowed, all children of slaves born after the 31st of December 1905 are free. For certain public works the Germans enforce a system of compulsory labour. Efforts are made by instruction in government and mission schools to spread a knowledge of the German language among the natives, in order to fit them for subordinate posts in administrative offices, such as the customs. Native chiefs in the interior are permitted to help in the administration of justice. The Mission du Sacré Cœur in Bagamoyo, the oldest mission in the colony, has trained many young negroes to be useful mechanics. The number of native Christians is small. The Moslems have vigorous and successful missions.

Chief Towns.—The seaports of the colony are Tanga (pop. about 6000), Bagamoyo 5000 (with surrounding district some 18,000), Dar-es-Salaam 24,000, Kilwa 5000, (these have separate notices), Pangani, Sadani, Lindi and Mikindani. Pangani (pop. about 3500) is situated at the mouth of the river of the same name; it serves a district rich in tropical products, and does a thriving trade with Zanzibar and Pemba. Sadani is a smaller port midway between Pangani and Bagamoyo. Lindi (10° 0′ S., 39° 40′ E.) is 80 m. north of Cape Delgado. Lindi (Swahili for The Deep Below) Bay runs inland 6 m. and is 3 m. across, affording deep anchorage. Hills to the west of the bay rise over 1000 ft. The town (pop. about 4000) is picturesquely situated on the north side of the bay. The Arab boma, constructed in 1800, has been rebuilt by the Germans, who have retained the fine sculptured gateway. Formerly a rendezvous for slave caravans Lindi now has a more legitimate trade in white ivory. Mikindani is the most southern port in the colony. Owing to the prevalence of malaria there, few Europeans live at the town, and trade is almost entirely in the hands of Banyans.

Inland the principal settlements are Korogwe, Mrogoro, Kilossa, Mpapua and Tabora. Korogwe is in the Usambara hills, on the north bank of the Pangani river, and is reached by railway from Tanga. Mrogoro is some 140 m. due west of Dar-es-Salaam, and is the first important station on the road to Tanganyika. Kilossa and Mpapua are farther inland on the same caravan route. Tabora (pop. about 37,000), the chief town of the Wanyamwezi tribes, occupies an important position on the central plateau, being the meeting-place of the trade routes from Tanganyika, Victoria Nyanza and the coast. In the railway development of the colony Tabora is destined to become the central junction of lines going north, south, east and west.

On Victoria Nyanza there are various settlements. Mwanza, on the southern shore, is the lake terminus of the route from Bagamoyo: Bukoba is on the western shore, and Schirati on the eastern shore; both situated a little south of the British frontier. On the German coast of Tanganyika are Ujiji (q.v.), pop. about 14,000, occupying a central position; Usumbura, at the northern end of the lake where is a fort built by the Germans; and Bismarckburg, near the southern end. On the shores of the lake between Ujiji and Bismarckburg are four stations of the Algerian “White Fathers,” all possessing churches, schools and other stone buildings. Langenburg is a settlement on the north-east side of Lake Nyasa. The government station, called New Langenburg, occupies a higher and more healthy site north-west of the lake. Wiedhafen is on the east side of Nyasa at the mouth of the Ruhuhu, and is the terminus of the caravan route from Kilwa.

Productions.—The chief wealth of the country is derived from agriculture and the produce of the forests. From the forests are obtained rubber, copal, bark, various kinds of fibre, and timber (teak, mahogany, &c.). The cultivated products include coffee, the coco-nut palm, tobacco, sugar-cane, cotton, vanilla, sorghum, earth-nuts, sesame, maize, rice, beans, peas, bananas (in large quantities), yams, manioc and hemp. Animal products are ivory, hides, tortoise-shell and pearls. On the plateaus large numbers of cattle, goats and sheep are reared. The natives have many small smithies. Gold, coal, iron, graphite, copper and salt have been found. Garnets are plentiful in the Lindi district, and agates, topaz, moonstone and other precious stones are found in the colony. The chief gold and iron deposits are near Victoria Nyanza. In the Mwanza district are conglomerate reefs of great extent. Mining began in 1905, Mica is mined near Mrogoro. The chief exports are sisal fibre, rubber, hides and skins, wax, ivory, copra, coffee, ground-nuts and cotton. The imports are chiefly articles of food, textiles, and metals and hardware. More than half the entire trade, both export and import, is with Zanzibar. Germany takes about 30% of the trade. In the ten years 1896–1905 the value of the external trade increased from about £600,000 to over £1,100,000. In 1907 the imports were valued at £1,190,000, the exports at £625,000.

Numerous companies are engaged in developing the resources of the country by trading, planting and mining. The most important is the Deutsch-Ostafrikanische Gesellschaft, founded in 1885, which has trading stations in each seaport, and flourishing plantations in various parts of the country. It is the owner of vast tracts of land. From 1890 to 1903 this company was in possession of extensive mining, railway, banking and coining rights, but in the last-named year, by agreement with the German government, it became a land company purely. The company has a right to a fifth part of the land within a zone of 10 m. on either side of any railway built in the colony previously to 1935. In addition to the companies a comparatively large number of private individuals have laid out plantations, Usambara and Pare having become favourite districts for agricultural enterprise. In the delta of the Rufiji and in the Kilwa district cotton-growing was begun in 1901. The plantations are all worked by native labour. The government possesses large forest reserves.

Communications.—Good roads for foot traffic have been made from the seaports to the trading stations on Lakes Nyasa, Tanganyika and Victoria. Caravans from Dar-es-Salaam to Tanganyika take 60 days to do the journey. The lack of more rapid means of communication hindered the development of the colony and led to economic crises (1898–1902), which were intensified, and in part created, by the building of a railway in the adjacent British protectorate from Mombasa to Victoria Nyanza, the British line securing the trade with the lake. At that time the only railway in the country was a line from Tanga to the Usambara highlands. This railway passes through Korogwe (52 m. from Tanga) and is continued via Mombo to Wilhelmstal, a farther distance of 56 m. The building of a trunk line from Dar-es-Salaam to Mrogoro (140 m.), and ultimately to Ujiji by way of Tabora, was begun in 1905. Another proposed line would run from Kilwa to Wiedhafen on Lake Nyasa. This railway would give the quickest means of access to British Central Africa and the southern part of Belgian Congo. On each of the three lakes is a government steamer. British steamers on Victoria Nyanza maintain communication between the German stations and the take terminus of the Uganda railway. The German East Africa Line of Hamburg runs a fleet of first-class steamers to East Africa, which touch at Tanga, Dar-es-Salaam and Zanzibar. There is a submarine cable from Dar-es-Salaam to Zanzibar, and an overland line connecting all the coast stations. Administration, Revenue, &c.—For administrative purposes the country is divided into districts (Bezirksämter), and stations (Stationsbezirke). Each station has a chief, who is subordinate to the official of his district, these in their turn being under the governor, who resides in Dar-es-Salaam. The governor is commander of the colonial force, which consists of natives under white officers. District councils are constituted, on which the European merchants and planters are represented. Revenue is raised by taxes on imports and exports, on licences for the sale of land and spirituous liquors, and for wood-cutting, by harbour and other dues, and a hut tax on natives. The deficiency between revenue and expenditure is met by a subsidy from the imperial government. In no case during the first twenty-one years’ existence of the colony had the local revenue reached 60% of the local expenditure, which in normal years amounted to about £500,000. In 1909, however, only the expenditure necessary for military purposes (£183,500) was received by way of subsidy.

History.—Until nearly the middle of the 19th century only the coast lands of the territory now forming German East Africa were known either to Europeans or to the Arabs. When at the beginning of the 16th century the Portuguese obtained possession of the towns along the East African coast, they had been, for periods extending in some cases fully five hundred years, under Arab dominion. After the final withdrawal of the Portuguese in the early years of the 18th century, the coast towns north of Cape Delgado fell under the sway of the Muscat Arabs, passing from them to the sultan of Zanzibar. From about 1830, or a little earlier, the Zanzibar Arabs began to penetrate inland, and by 1850 had established themselves at Ujiji on the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika. The Arabs also made their way south to Nyasa. This extension of Arab influence was accompanied by vague claims on the part of the sultan of Zanzibar to include all these newly opened countries in his empire. How far from the coast the real authority of the sultan extended was never demonstrated. Zanzibar at this time was in semi-dependence on India, and British influence was strong at the court of Bargash, who succeeded to the sultanate in 1870. Bargash in 1877 offered to Sir (then Mr) William Mackinnon a lease of all his mainland territory. The offer, made in the year in which H. M. Stanley’s discovery of the course of the Congo initiated the movement for the partition of the continent, was declined. British influence was, however, still so powerful in Zanzibar that the agents of the German Colonization Society, who in 1884 sought to secure for their country territory on the east coast, deemed it prudent to act secretly, so that both Great Britain and Zanzibar might be confronted with accomplished facts. Making their way inland, three young Germans, Karl Peters, Joachim Count Pfeil and Dr Jühlke, concluded a “treaty” in November 1884 with a chieftain in Usambara who was declared to be independent of Zanzibar. Other treaties followed, and on the 17th of February 1885, the German emperor granted a charter of protection to the Colonization Society. The German acquisitions were resented by Zanzibar, but were acquiesced in by the British government (the second Gladstone administration). The sultan was forced to acknowledge their validity, and to grant a German company a lease of his mainland territories south of the mouth of the Umba river, a British company formed by Mackinnon taking a lease of the territories north of that point. The story of the negotiations between Great Britain, Germany and France which led to this result is told elsewhere (see Africa, section 5). By the agreement of the 1st of July 1890, between the British and German governments, and by agreements concluded between Germany and Portugal in 1886 and 1894, and Germany and the Congo Free State in 1884 and later dates, the German sphere of influence attained its present area. On the 28th of October 1890 the sultan of Zanzibar ceded absolutely to Germany the mainland territories already leased to a German company, receiving as compensation £200,000.

While these negotiations were going on, various German companies had set to work to exploit the country, and on the 16th of August 1888 the German East African Company, the lessee of the Zanzibar mainland strip, took over the administration from the Arabs. This was followed, five days later, by a revolt of all the coast Arabs against German rule—the Germans, raw hands at the task of managing Orientals, having aroused intense hostility by their brusque treatment of the dispossessed rulers. The company being unable to quell the revolt, Captain Hermann Wissmann—subsequently Major Hermann von Wissmann (1853–1905)—was sent out by Prince Bismarck as imperial commissioner. Wissmann, with 1000 soldiers, chiefly Sudanese officered by Germans, and a German naval contingent, succeeded by the end of 1889 in crushing the power of the Arabs. Wissmann remained in the country until 1891 as commissioner, and later (1895–1896) was for eighteen months governor of the colony—as the German sphere had been constituted by proclamation (1st of January 1897). Towards the native population Wissmann’s attitude was conciliatory, and under his rule the development of the resources of the country was pushed on. Equal success did not attend the efforts of other administrators; in 1891–1892 Karl Peters had great trouble with the tribes in the Kilimanjaro district and resorted to very harsh methods, such as the execution of women, to maintain his authority. In 1896 Peters was condemned by a disciplinary court for a misuse of official power, and lost his commission. After 1891, in which year the Wahehe tribe ambushed and almost completely annihilated a German military force of 350 men under Baron von Zelewski, there were for many years no serious risings against German authority, which by the end of 1898 had been established over almost the whole of the hinterland. The development of the country was, however, slow, due in part to the disinclination of the Reichstag to vote supplies sufficient for the building of railways to the fertile lake regions. Count von Götzen (governor 1901–1906) adopted the policy of maintaining the authority of native rulers as far as possible, but as over the greater part of the colony the natives have no political organizations of any size, the chief burden of government rests on the German authorities. In August 1905 serious disturbances broke out among the Bantu tribes in the colony. The revolt was due largely to resentment against the restrictions enforced by the Germans in their efforts at civilization, including compulsory work on European plantations in certain districts. Moreover, it is stated that the Herero in rebellion in German South-west Africa sent word to the east coast natives to follow their example, an instance of the growing solidarity of the black races of Africa. Though the revolt spread over a very large area, the chief centre of disturbance was the region between Nyasa and the coast at Kilwa and Lindi. Besides a number of settlers a Roman Catholic bishop and a party of four missionaries and nuns were murdered in the Kilwa hinterland, while nearer Nyasa the warlike Wangoni held possession of the country. The Germans raised levies of Masai and Sudanese, and brought natives from New Guinea to help in suppressing the rising, besides sending naval and military contingents from Germany. In general, the natives, when encountered, were easily dispersed, but it was not until March 1906 that the coast regions were again quiet. In July following the Wangoni were beaten in a decisive engagement. It was officially stated that the death-roll for the whole war was not below 120,000 men, women and children. In 1907 a visit was paid to the colony by Herr B. Dernburg, the colonial secretary. As a result of this visit more humane methods in the treatment of the natives were introduced, and measures taken to develop more fully the economic resources of the country.

Authorities.—S. Passarge and others, Das deutsche Kolonialreich, Erster Band (Leipzig, 1909); P. Reichard, Deutsch Ostafrika, das Land und seine Bewohner (Leipzig, 1892); F. Stuhlmann, Mit Emin Pasha im Herzen von Afrika (Berlin, 1894); Brix Foerster, Deutsch-Ostafrika; Geographie und Geschichte (Leipzig, 1890); Oscar Baumann, In Deutsch-Ostafrika während des Aufstands (Vienna, 1890), Usambara und seine Nachbargebiete (Berlin, 1891), and Durch Massailand zur Nilquelle (Berlin, 1894). For special studies see P. Samassa, Die Besiedelung Deutsch-Ostafrikas (Leipzig, 1909); A. Engler, Die Pflanzenwelt Ost-Afrikas und der Nachbargebiete (Berlin, 1895–1896) and other works by the same author; Stromer von Reichenbach, Die Geologie der deutschen Schutzgebiete in Afrika (Munich and Leipzig, 1896); W. Bornhardt, Deutsch-Ostafrika (Berlin, 1898); F. Fullerborn, Beiträge zur physischen Anthropologie der Nord-Nyassaländer (Berlin, 1902), a fine series of pictures of native types, and Das Deutsche Nyassa- und Ruwuma-gebiet, Land und Leute (Berlin, 1906); K. Weule, Native Life in East Africa (London, 1909); Hans Meyer, Der Kilimandjaro (Berlin, 1900) and Die Eisenbahnen im tropischen Afrika (Leipzig, 1902); J. Strandes, Die Portugiesenzeit von Deutsch- u. Englisch-Ostafrika (Berlin, 1899), a valuable monograph on the Portuguese period. See also British Official Reports on East Africa (specially No. 4221 ann. ser.), the German White Books and annual reports, the Mitteilungen aus den deutschen Schutzgebiete, and the Deutsches Kolonialblatt, published fortnightly at Berlin since 1890. The Deutscher Kolonial-Atlas has maps on the 1:1,000,000 scale. (F. R. C.)