Troodon

Troodon (or Troödon) is a genus of relatively small, bird-like dinosaurs, from the later part of the Cretaceous period, 75 - 65 million years ago.[1] The alternate spelling Troödon shows that the 'o's are pronounced separately, as in 'zoology'.

| Troodon Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, 75–65 mya | |

|---|---|

| |

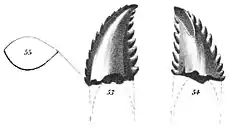

| Illustration of the T. formosus holotype tooth | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Troodontidae |

| Subfamily: | †Troodontinae Gilmore, 1924 |

| Genus: | †Troodon Leidy, 1856 |

| Type species | |

| †Troodon formosus Leidy, 1856 | |

They were probably carnivorous, but details of their teeth are a bit unusual. Some experts suggest they may have included plant material in their diet, but this is not a majority view.

Discovered in central Montana in 1855, it was among the first dinosaurs found in North America. Its species ranged widely, with fossil remains recovered from as far north as Alaska, and the Judith River formation of Alberta, and as far south as Wyoming and even possibly Texas and New Mexico.[2]

Troodon had a large brain in proportion to its body weight. It had a sickle claw, an enlarged and retractable second toe claw bone. Troodon had 122 teeth.[2] The size and shape of the leg bones show that the Troodon would have been a fast runner.[2] The view that Troodon was a predator is supported by its sickle claw on the foot and apparently good binocular vision.

Troodons size ranged widely. In general, individuals that lived further north were larger than those that lived in more southern areas. Troodons in Alaska were especially large, up to 12 feet long, 5 feet tall, and weighing up to 175 pounds. Meanwhile, Troodons that lived in more southern locations were only around 7 feet long, 3 feet tall, and weighed up to 50 pounds, about the size of a Velociraptor. Very likely Troodon had feathers, but no fossil evidence for feathers has yet been found.

There has been a lot of debate about which specimens, all very incomplete, should be called Troodon. The genus now includes specimens previously classified as Stenonychosaurus.

Troodon nests full of eggs have been found in Montana. When scientists CAT-scanned them, they found baby Troodon skeleton embryos inside of them. They found skeletons of a small plant-eating dinosaur named Orodromeus with the eggs, as well as a skeleton of an adult Troodon. At first, it was believed that the eggs had belonged to the Orodromeus, and that the Troodon was there intending to rob the nest.[3]

However, it was later discovered that the eggs belonged to the Troodon when baby Troodon embryos were found inside the eggs. It is now believed that the adults had killed the Orodromeus and brought them back to feed their babies.[4] Troodons laid up to 24 eggs in their nests which were earth mounds. They were able to lay two eggs at a time, so large clutches would take two weeks to lay.[2]

A 2017 description had redeemed the validity of Stenonychosaurus and had created a new genus from separate bones naming them Lateniventrix, limiting Troodon to a few teeth.[5]

References

- Paul G.S. 1988. Predatory dinosaurs of the world. New York: Simon and Schuster, p. 396. ISBN 0-671-61946-2

- Mackovicky, Peter J. & Norell, Mark A. 2004. Troodontidae. In Weishampel, David B; Dodson, Peter & Osmólska, Halszka. The Dinosauria. 2nd ed, Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 184–195. ISBN 0-520-24209-2

- Horner, John R. 1984. "The nesting behavior of dinosaurs". Scientific American, 250:130-137.

- Varricchio, David J.; Horner, John J.; Jackson, Frankie D. (2002). "Embryos and eggs for the Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Troodon formosus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (3): 564–576. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0564:EAEFTC]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 85728452.

- van der Reest A.J. & Currie P.J. 2017. Troodontids (Theropoda) from the Dinosaur Park Formation, Alberta, with a description of a unique new taxon: implications for deinonychosaur diversity in North America. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 54 (9): 919–935.