Spinosauridae

Spinosauridae (meaning 'spined lizards') is a family of carnivorous theropod dinosaurs from the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. They are unique among other meat-eating dinosaurs from their more water-based lifestyle, which involved a diet of mostly fish. Spinosaurid fossils have been found all over the world, including Asia, South America, Europe, Africa, and Australia.

| Spinosauridae Temporal range: Late Jurassic–Late Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeletal reconstruction of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, National Geographic Museum, Washington, D.C. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Avetheropoda |

| Infraorder: | †Carnosauria |

| Family: | †Spinosauridae Stromer, 1915 |

| Type species | |

| Spinosaurus aegyptiacus Stromer, 1915 | |

| Subgroups | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

Spinosaurids had longer arms than most theropods, the claw on the first finger was usually the largest. They evolved jaws like those of crocodiles, and their teeth were long and cone-shaped, made to trap prey in their mouths instead of tearing them apart. Because of this, their teeth usually did not have the strong knife-like edges (called serrations) of a lot of other meat-eating dinosaurs.[1][2]

The family contains Spinosaurus, the first spinosaurid discovered, and the largest carnivorous dinosaur we know of. Paleontologists suggest it might have reached up to 15 meters (49 ft.) in length.[3]

Paleobiology

A study made in 2010 by Roman Amiot and his colleagues found that spinosaurids had very semiaquatic (living partly in water, and partly on land) lifestyles, this means they lived in habitats like those of hippopotamuses, crocodiles, and turtles, making them very unusual compared to other theropods. It also means they could exist at the same time and place as other large predators without competing for food. For example; Carcharodontosaurus, which lived at the same time as Sigilmassasaurus and Spinosaurus, did not need to fight with either of those animals for prey; those spinosaurids ate fish, while Carcharodontosaurus was on land most of the time, hunting smaller dinosaurs.[4]

Classification

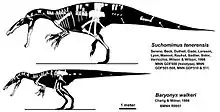

The family "Spinosauridae" was named by the German paleontologist Ernst Stromer in 1915, he was the one that discovered the first genus in the group, Spinosaurus. And as scientists discovered more fossils of its close relatives, the family was eventually split into two subfamilies: Baryonychinae, and Spinosaurinae. This was done because of differences in the anatomy of their skulls and teeth.

This is a cladogram made in 2017 showing the relationships between different spinosaurids inside of megalosauroidea.[5]

| Megalosauroidea |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Sereno, Paul C., Allison L. Beck, Didier B. Dutheil, Boubacar Gado, Hans C. E. Larsson, Gabrielle H. Lyon, Jonathan D. Marcot, et al. 1998. “A Long-Snouted Predatory Dinosaur from Africa and the Evolution of Spinosaurids.” Science 282 (5392): 1298–1302. doi:10.1126/science.282.5392.1298.

- Rayfield, Emily J. 2011. “Structural Performance of Tetanuran Theropod Skulls, with Emphasis on the Megalosauridae, Spinosauridae and Carcharodontosauridae.” Special Papers in Palaeontology 86 (November). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/250916680_Structural_performance_of_tetanuran_theropod_skulls_with_emphasis_on_the_Megalosauridae_Spinosauridae_and_Carcharodontosauridae.

- Ibrahim, Nizar; Sereno, Paul C.; Dal Sasso, Cristiano; Maganuco, Simone; Fabri, Matteo; Martill, David M.; Zouhri, Samir; Myhrvold, Nathan; Lurino, Dawid A. (2014). "Semiaquatic adaptations in a giant predatory dinosaur". Science. 345 (6204): 1613–6. Bibcode:2014Sci...345.1613I. doi:10.1126/science.1258750. PMID 25213375. S2CID 34421257. Supplementary Information

- Amiot, R.; Buffetaut, E.; Lécuyer, C.; Wang, X.; Boudad, L.; Ding, Z.; Fourel, F.; Hutt, S.; Martineau, F.; Medeiros, A.; Mo, J.; Simon, L.; Suteethorn, V.; Sweetman, S.; Tong, H.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, Z. (2010). "Oxygen isotope evidence for semi-aquatic habits among spinosaurid theropods". Geology. 38 (2): 139–142. Bibcode:2010Geo....38..139A. doi:10.1130/G30402.1.

- Sales, M.A.F.; Schultz, C.L. (2017). "Spinosaur taxonomy and evolution of craniodental features: Evidence from Brazil". PLOS ONE. 12 (11): e0187070. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1287070S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0187070. PMC 5673194. PMID 29107966.

Other websites

- Spinosauridae

- Spinosauridae on the Theropod Database