Sentō

Sentō are Japanese public bathhouses. People take baths together there. Many Japanese people think of sentō as an important part of Japanese culture, with its manners and ideas about communities.[1][2][3]

Sentō are not the same as onsen. Onsen are baths built on natural hot springs. Onsen water has dissolved rock in it. Sentō water is either tap water or well water.[4] Some sentō may add good-smelling plants or bath salts to the water. Sentō cost less than onsen to visit.[5]

Today, sentō are not as popular as they once were. This is because people have bathtubs and showers in their homes.[6] They do not need to go to a sentō to clean. Many people still go to sentō, but they go to enjoy the water and relax.[1] The Tokyo Sentō Association makes sure going to a sentō does not become expensive because they want people to be able to go to sentō.[7] Local organizations decide the price. For example, in Tokyo, the Tokyo Sentō Association decides the price.[7][3] In 2020, the price to go to a sentō in Tokyo was ¥480,[6] or a little over US$4.10.

Architecture

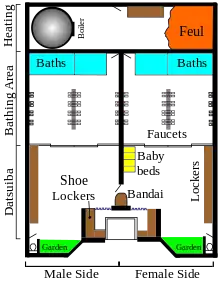

On the outside, some sentō look like temples. The entrance has a Japanese curtain called a noren.[7] Noren at sentō are usually blue. Most sentō have concrete or steel chimneys for the boilers that heat the water. Sometimes, a person can find a neighborhood's sentō by looking for a building with this kind of special chimney.[8]

The dressing area is usually made in the traditional Japanese style, with wood and dark colors. The bathing area are usually made with tiles and is full of light. Japanese people think of this style as Western.[8]

Sentō have separate places for men and women, but young children can go to either side. Babies often go with the women. Fathers take boys and very young girls to the men's side.[1] Sometimes there is a door between the men's and women's sides. Children are allowed to go through the door.[8]

Many sentō have a large mural, or wall painting, near the tubs. Many are landscapes or pictures of Mount Fuji.[6] The water in the air is bad for the paint, so the murals wear out. Repainting a mural in the one day a week that a sentō is closed is hard to do, so some sentō use tiled mosaics or a window that looks out on a garden for decoration instead.[8]

Some sentō owners and their families live in rooms at the back of the building.[8]

History

People built the first sentō during the Nara period, in the 700s.[9] The first people to use sentō were monks.[9] They used the sentō for ritual purification. Later, more sentō were built for ordinary people to go and get clean. By 1700, most of the neighborhoods in Tokyo, then called Edo, had their own bathhouse. Many of the sentō of that time were steam baths, not soaking baths. They did not have windows, so the bathers could not see very well. Sometimes the water was dark and dirty.[1]

In 1868, the Meiji Restoration took away some of the class system of Japan. After that, many former nobles or samurai took baths with the regular people in sentō.[1]

Tsurusawa Monzaemon had the idea for modern sentō in 1878. Instead of a steam bath, he built a big tub that the bather could sit down in. He put windows in his sentō so there would be light to see by. This made it easier to see whether the water was clean. People liked these new sentō and soon built many more of them. In 1885, the government said no one could build the old, dark sentō any more. All new sentō had to be light so they could be kept clean. They also passed a law against men and women bathing together, but no one cared about it until after many foreigners began to visit Japan later in the Meiji period (late 1800s).[1]

In the 20th century, sentō became less popular. To keep customers, sentō owners put in bubblers, exercise equipment, saunas, electric shocks and other things bathers could not get at home. In 1972, there were about 21,200 sentō in Japan. This went down to 13,250 in 1985.[1] There were 499 sentō in Tokyo as of 2021.[6]

Super sentō

People began building super sentō in the second half of the 20th century. Super sentō have more things to do than regular sentō. Some have water slides, swimming pools, or restaurants. Super sentō are meant to be fun instead of relaxing. [10]

Manners

Before entering, visitors take off their shoes and put them in shoe lockers. At sentō in Japan today, it is not good manners to clean one's body in the bathtub. Bathers must shower before getting in the water. This keeps dirt, sweat and other things from making the water dirty. Many sentō provide soap and towels. Bathers sit on a stool in the shower. The bathers must not wear any clothes or swimsuits in the sentō. Bathers may use towels at the sentō or bring their own, but the towel must not go in the water.[7] Bathers put the towels on their heads instead. People with long hair tie it up so it does not get in the water.

Pictures

.jpg.webp) Showers and stools at a sentō.

Showers and stools at a sentō..jpg.webp) This sentō has an arched entrance like a temple has.

This sentō has an arched entrance like a temple has. A blue noren at the entrance of a sentō.

A blue noren at the entrance of a sentō. A sentō with a blue noren outside.

A sentō with a blue noren outside. A super sentō.

A super sentō.

Related pages

References

- Scott Clark (1992). "The Japanese Bath: Extraordinarily Ordinary". In Joseph Jay Tobin (ed.). Re-made in Japan: Everyday Life and Consumer Taste in a Changing Society. Yale University Press. pp. 89–104. ISBN 0300060823. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- Suemedha Sood (November 29, 2012). "The origins of bathhouse culture around the world". BBC Travel. Archived from the original on July 12, 2021. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- "About Sento". Tokyo Sento Association. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- Takamitsu Jimura (August 16, 2021). "Onsen and Japanese-style inns". Cultural Heritage and Tourism in Japan. Taylor & Francis. p. 99. ISBN 9780429673122. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- Takahiro Takiguchu (November 13, 2019). "Japanese public baths: The difference between a sento and an onsen". Stripes. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- Casey Baseel. "State of the sento — Tokyo's public baths are disappearing, but statistics show a sliver of hope". Japan Today. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- Mark Buckton (July 17, 2017). "Tokyo's public baths: How to enjoy a sento". CNN Travel. Archived from the original on July 14, 2021. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- Scott Clark (1994). Japan, A View from the Bath: A study of the significance of bathing in Japanese mythology and the historical development of communal bathing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824863067. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- Lily Crossley-Baxter (February 3, 2020). "Japan's naked art of body positivity". BBC Travel. Archived from the original on July 10, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- Yoshiko Uchida (January 7, 2019). "Modern sauna hot spots in Japan shed old-man image". Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 8, 2021.