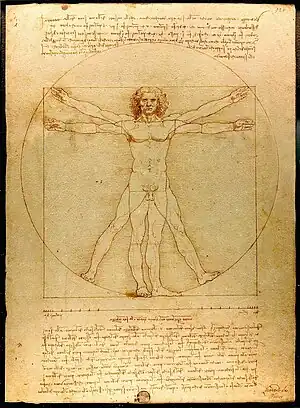

Renaissance man

The term Renaissance man or polymath is used for a very clever man who is good at many different things. It is named after the Renaissance period of history (from the 14th century to the 16th or 17th century in Europe). Two of the best-known people from this time were Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. Leonardo was a famous painter but he was also a scientist, philosopher, engineer, and mathematician. Michelangelo was an extraordinary sculptor, painter, architect and poet. They are known as two of the highest examples of what a Renaissance man is.[1][2]

But the term "Renaissance man" is also often used for extraordinary people not from the Renaissance period. It can be used for anyone who is very clever at many different things, no matter when that person lived. Albert Schweitzer was a 20th century "Renaissance man" who was a theologian, musician, philosopher and doctor.[3] Benjamin Franklin was a "Renaissance man" who lived in the 18th century and was an author and printer, politician, scientist, inventor and soldier.[4]

Renaissance period

Uomo Universale (transl. Universal man) was the original concept of the Renaissance man. It was an ideal of the Italian Renaissance. One example is the saying by Leone Battista Alberti that "a man can do all things if he will".[5] Many Renaissance men from this time are still famous today:

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) Italian painter, sculptor, engineer, astronomer, anatomist, biologist, geologist, physicist, architect, musician, philosopher, and humanist.[6][7][8][9][10]

- Michelangelo (March 6, 1475 – February 18, 1564) was an Italian Renaissance painter, sculptor, architect, poet, engineer, and theologian.

- Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) was a Florentine statesman, philosopher, poet, author, playwright, songwriter, classicist, military scientist, political thinker, and historian.

- Leone Battista Alberti (1404–1472) was an Italian author, artist, architect, poet, priest, linguist, philosopher, and cryptographer.

- Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) was an Italian scientist, mathematician, astronomer, physicist, and philosopher.

Other polymaths

Ancient history

- Aristotle (Greek: Ἀριστοτέλης, Aristotle) (384 BC – 322 BC) was a Greek philosopher who studied and wrote about many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, politics, government, ethics, biology and zoology.

- Archimedes (Greek: Ἀρχιμήδης; c. 287 BC – c. 212 BC) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, inventor, and astronomer.

Medieval history

- Abū Alī ibn Sīnā (Avicenna) (980–1037), was a Persian physician, pharmacologist, philosopher, mathematician, astronomer, chemist, Hanafi jurist and theologian, scientist, statesman and soldier.[11][12]

- Ibn Rushd (Averroes) (1126–1198), an Andalusian Arab philosopher, physician, jurist, astronomer, mathematician, and theologian.[13][14]

- Roger Bacon, O.F.M. (c. 1214–1294), also known as Doctor Mirabilis (Latin: "wonderful teacher"), an English Franciscan friar who was a philosopher, theologian and scientist. One of the first people to perform scientific experiments in a modern manner.

Modern history

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) German writer, poet, critic, playwright, and novelist.

- Robert Hooke (1635–1703) was an English scientist, mathematician, natural philosopher, and architect.

- Isaac Newton (1643–1727) was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, theologian, natural philosopher and alchemist. His development of calculus, and his three laws of motion were landmarks in applied mathematics.

- Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716) was a German philosopher, theologian, physicist, mathematician, historian, librarian and inventor.

- Mikhail Lomonosov (1711–1765) was a Russian poet, educator, artist, physicist and chemist education.

- Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826). American president who was a horticulturist, architect, archaeologist, inventor, and founder of a university.

- Rabindranath Tagore (7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was a Bengali poet, artist, playwright, novelist, educationist, social reformer, nationalist, business-manager and composer.

- Albert Einstein (14 March 1879 – 15 April 1955) was a German-American physicist, mathematician, cosmologist, professor, refrigeration engineer (patent), patent analyst, essayist, activist, pianist, and recital violinist.[15][16]

- G. Spencer-Brown (2 April 1923 -2016) was an English mathematician and writer of Laws of Form.

References and notes

- BBC: Science & Nature

- John Addington Symonds, "The Renaissance Man", The Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti, Kindle Edition

- "Albert Schweitzer Fellowship". Archived from the original on 2011-10-12. Retrieved 2017-10-13.

- Benjamin Franklin: Early American Renaissance Man

- "Renaissance man". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- Johnston, Robert K.; J Walker Smith (2003). Life Is Not Work, Work Is Not Life: Simple Reminders for Finding Balance in a 24-7 World. Council Oak Books. "...the prodigious polymath of the Italian Renaissance. Painter, sculptor, engineer, astronomer, anatomist, biologist, geologist, physicist, architect, philosopher, humanist."p. 1

- Elmer, Peter; Nicholas Webb, Roberta Wood (2000). The Renaissance in Europe: An Anthology. Yale University Press. "The following selection... shows why this famous Renaissance polymath considered painting to be a science..."

- Elmer, Peter; Webb, Nick; Wood, Roberta (2000). The Renaissance in Europe: An Anthology. p. 180. ISBN 0-300-08222-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - Freud, Sigmund (1999). Leonardo Da Vinci: A Memory of His Childhood. Routledge. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-415-21089-8.

- Johnston, Robert K.; J Walker Smith (2003). Life Is Not Work, Work Is Not Life: Simple Reminders for Finding Balance in a 24-7 World. Council Oak Books. p. 1

- Richard Covington, "Rediscovering Arabic Science", Saudi Aramco World, May/June 2007.

- Charles F. Horne (1917), ed., The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East Vol. VI: Medieval Arabia, pages 90–91. Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, New York. (cf. Ibn Sina (Avicenna) (973–1037): On Medicine, c. 1020 CE Archived 2007-10-30 at the Wayback Machine, Medieval Sourcebook.)

- Top 100 Events of the Millennium Archived 2012-04-02 at the Wayback Machine, Life magazine.

- Caroline Stone, "Doctor, Philosopher, Renaissance Man", Saudi Aramco World, May-June 2003, p. 8–15.

- Garreth Dottin (Nov 17, 2016). "Einstein's Violin: The Hidden Connections between Scientific Breakthroughs and Art". medium.com. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- Tahiat Mahboob (March 14, 2017). "Albert Einstein: 10 things you might not know about his love for music". cbcmusic.ca. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

Further reading

- Polymath: A Renaissance Man Archived 2006-01-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Polymath -Citizendium

- "History", "Mathematic", "Polymath" and "Polyhistor" in one or more of: Chamber's Dictionary of Etymology, The Oxford Dictionary of Word Histories, The Cassell Dictionary of Word Histories