Planck constant

The Planck constant (Planck's constant) says how much the energy of a photon increases when the frequency of its electromagnetic wave increases by 1 (In SI Units). It is named after the physicist Max Planck. The Planck constant is a fundamental physical constant. It is written as h.

The Planck constant has dimensions of physical action: energy multiplied by time, or momentum multiplied by distance. In SI units, the Planck constant is expressed in joule seconds (J⋅s) or (N⋅m⋅s) or (kg⋅m2⋅s−1). The symbols are defined here.

In SI Units the Planck constant is exactly 6.62607015×10−34 J·s (by definition).[1] Scientists have used this quantity to calculate measurements like the Planck length and the Planck time.

Background

| Symbols used in this article. | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

Between 1670 and 1900 scientists discussed the nature of light. Some scientists believed that light consisted of many millions of tiny particles. Other scientists believed that light was a wave.[2]

Light: waves or particles?

In 1678, Christiaan Huygens wrote the book Traité de la lumiere ("Treatise on light"). He believed that light was made up of waves. He said that light could not be made up of particles because light from two beams do not bounce off each other.[3][4] In 1672, Isaac Newton wrote the book Opticks. He believed that light was made up of red, yellow and blue particles which he called corpusles. Newton explained this by his "two prism experiment". The first prism broke light up into different colours. The second prism merged these colours back into white light.[5][6]

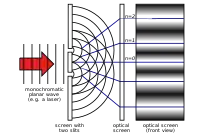

During the 18th century, Newton's theory was given the most attention.[7] In 1803, Thomas Young described the "double-slit experiment".[4] In this experiment, light going through two narrow slits interferes with itself. This causes a pattern which shows that light is made up of waves. For the rest of the nineteenth century, the wave theory of light was given the most attention. In the 1860s, James Clerk Maxwell developed equations that described electromagnetic radiation as waves.

The theory of electromagnetic radiation treats light, radio waves, microwaves and many other types of wave as the same thing except that they have different wavelengths. The wavelength of the light we can see with our eyes is roughly between 400 and 600 nm.[Note 1] The wavelength of radio waves varies from 10 m to 1500 m and the wavelength of microwaves is about 2 cm. In a vacuum, all electromagnetic waves travel at the speed of light. The frequency of the electromagnetic wave is given by:

- .

The symbols are defined here.

Black body radiators

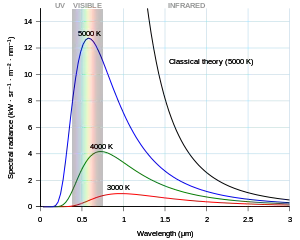

All warm things give off thermal radiation, which is electromagnetic radiation. For most things on Earth this radiation is in the infra-red range, but something very hot (1000 °C or more), gives off visible radiation, that is, light. In the late 1800's many scientists studied the wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation from black-body radiators at different temperatures.

Rayleigh-Jeans Law

Lord Rayleigh first published the basics of the Rayleigh-Jeans law in 1900. The theory was based on the Kinetic theory of gasses. Sir James Jeans published a more complete theory in 1905. The law relates the quantity and wavelength of electromagnetic energy given off by a black body radiator at different temperatures. The equation describing this is:[8]

- .

For long-wavelength radiation, the results predicted by this equation corresponded well with practical results obtained in a laboratory. However, for short wavelengths (ultraviolet light) the difference between theory and practice were so large that it earned the nickname "the ultra-violet catastrophe".

Planck's Law

in 1895 Wien published the results of his studies into the radiation from a black body. His formula was:

- .

This formula worked well for short wavelength electromagnetic radiation, but did not work well with long wavelengths.

In 1900 Max Planck published the results of his studies. He tried to develop an expression for black-body radiation expressed in terms of wavelength by assuming that radiation consisted of small quanta and then to see what happened if the quanta were made infinitely small. (This is a standard mathematical approach). The expression was:[9]

- .

If the wavelength of light is allowed to become very large, then it can be shown that the Raleigh-Jeans and the Planck relationships are almost identical.

He calculated h and k and found that

- h = 6.55×10−27 erg·sec.

- k = 1.34×10−16 erg·deg-1.

The values are close to the modern day accepted values of 6.62606×10−34 and 1.38065×10−16 respectively. The Planck law agrees well with the experimental data, but its full significance was only appreciated several years later.

Quantum theory of light

It turns out that electrons are dislodged by the photoelectric effect if light reaches a threshold frequency. Below this no electrons can be emitted from the metal. In 1905 Albert Einstein published a paper explaining the effect. Einstein proposed that a beam of light is not a wave propagating through space, but rather a collection of discrete wave packets (photons), each with energy. Einstein said that the effect was due to a photon striking an electron. This demonstrated the particle nature of light.

Einstein also found that electromagnetic radiation with a long wavelength had no effect. Einstein said that this was because the "particles" did not have enough energy to disturb the electrons.[10][11][12]

Planck suggested[9] that the energy of each photon was related to the photon frequency by the Planck constant. This could be written mathematically as:

- .

Planck received the Nobel Prize in 1918 in recognition of the services he rendered to the advancement of Physics by his discovery of energy quanta. In 1921 Einstein received the Nobel Prize for linking the Planck constant to the photoelectric effect.

Application

The Planck constant is of importance in many applications. A few are listed below.

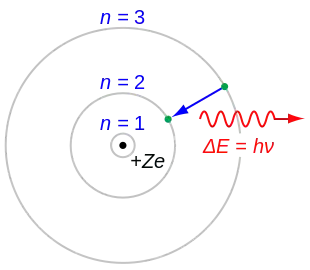

Bohr model of the atom

In 1913 Niels Bohr published the Bohr model of the structure of an atom. Bohr said that the angular momentum of the electrons going around the nucleus can only have certain values. These values are given by the equation

where

- L = angular momentum associated with a level.

- n = positive integer.

- h = Planck constant.

The Bohr model of the atom can be used to calculate the energy of electrons at each level. Electrons will normally fill up the lowest numbered states of an atom. If the atom receives energy from, for example, an electric current, electrons will be excited into a higher state. The electrons will then drop back to a lower state and will lose their extra energy by giving off a photon. Because the energy levels have specific values, the photons will have specific energy levels. Light emitted in this way can be split into different colours using a prism. Each element has its own pattern. The pattern for neon is shown alongside.

Heisenberg's uncertainty principle

In 1927 Werner Heisenberg published the uncertainty principle. The principle states that it is not possible to make a measurement without disturbing the thing being measured. It also puts a limit on the minimum disturbance caused by making a measurement.

In the macroscopic world these disturbances make very little difference. For example, if the temperature of a flask of liquid is measured, the thermometer will absorb a small amount of energy as it heats up. This will cause a small error in the final reading, but this error is small and not important.

In quantum mechanics things are different. Some measurements are made by looking at the pattern of scattered photons. One such example is Compton scattering. If both the position and momentum of a particle is being measured, the uncertainty principle states that there is a trade-off between the accuracy with which the momentum is measured and the accuracy with which the position is measured. The equation that describes this trade-off is:

where

- Δp = uncertainty in momentum.

- Δx = uncertainty in position.

- h = Planck constant.

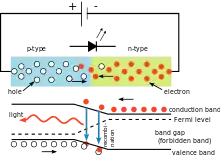

Colour of light emitting diodes

In the electric circuit shown on the right, the voltage drop across the light emitting diode (LED) depends on the material of the LED. For silicon diodes the drop is 0.6 V. However for LEDs it is between 1.8 V and 2.7 V. This information enables a user to calculate the Planck constant.[13]

The energy needed for one electron to jump the potential barrier in the LED material is given by

where

- Qe is the charge on one electron.

- VL is the voltage drop across the LED.

When the electron decays back again, it emits one photon of light. The energy of the photon is given by the same equation used in the photoelectric effect. If these equations are combined, the wavelength of light and the voltage are related by

The table below can be calculated from this relationship.

| Colour | Wavelength (nm)[Note 2] |

Voltage |

|---|---|---|

| red light | 650 | 1.89 |

| green light | 550 | 2.25 |

| blue light | 470 | 2.62 |

Value of the Planck constant and the kilogram redefinition

Since its discovery, measurements of h have become much better. Planck first quoted the value of h to be 6.55×10−27 erg·sec. This value is within 5% of the current value.

As of 3 March 2014, the best measurements of h in SI units is 6.62606957×10−34 J·s. The equivalent figure in cgs units is 6.62606957×10−27 erg·sec. The relative uncertainty of h is 4.4×10−8.

The reduced Planck constant (ħ) is a value that is sometimes used in quantum mechanics. It is defined by

- .

Planck units are sometimes used in quantum mechanics instead of SI. In this system the reduced Planck constant has a value of 1, so the value of the Planck constant is 2π.

Plancks constant can now be measured with very high precision. This has caused the BIPM to consider a new definition for the kilogram. The international prototype kilogram is no longer used to define the kilogram. Instead the BIPM defines the Planck constant to have an exact value. Scientists use this value and the definitions of the metre and the second to define the kilogram.[14]

Value of Theoretical Planck constant

The Planck constant can also be mathematically derived:

Here, is the permeability of free space, is the speed of light, is the electric charge of electron, is the Bohr's radius, and is the frequency of revolution of the electron in a hydrogen atom . When these constant values are substituted to the theoretical Planck constant, the theoretical Planck constant value is exactly equal to the experimental value.[15]

The Planck's constant elementary formula in terms of proton-to-electron mass ratio, the charge of electron, speed of light and vacuum permittivity is derived in.[16] It is expressed as follows:

where is the elementary charge of an electron, the mass of a proton, the mass of an electron, the vacuum permittivity, and the speed of light.

Related pages

Notes

- 0.0004 to 0.0006 mm

- 1000 nm = 0.001 mm

References

- SI Brochure: The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (9 ed.), BIPM, 2019, p. 128, retrieved 2020-01-12

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Light through the ages: Ancient Greece to Maxwell", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Christiaan Huygens", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Fitzpartick, Richard (14 July 2007). "Wave Optics". Lecture Notes. University of Texas. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- "Isaac Newton's theory on light and colours". The Royal Society. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- Duarte, FJ (May 2000). "Newton, Prisms, and the "Optiks" of Tunable Lasers" (PDF). Optics & Photonics News. 11 (5). Optical Society of America: 24–28. Bibcode:2000OptPN..11...24D. doi:10.1364/OPN.11.5.000024. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- "Optics". Encyclopeadia Britannica. Edinburgh: A Society of Gentlemen in Scotland. 1771.

- Lakoba, T. "Lecture notes and supporting material for MATH 235 - Mathematical Models and Their Analysis" (PDF). University of Vermont. 13. Black-body radiation and Planck's formula. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- Planck, Max (1901), "Ueber das Gesetz der Energieverteilung im Normalspectrum" (PDF), Ann. Phys., 309 (3): 553–63, Bibcode:1901AnP...309..553P, doi:10.1002/andp.19013090310. English translation: "On the Law of Distribution of Energy in the Normal Spectrum".

- Arrhenius, S (10 December 1922). The NobelPrize in Physics 1921, ALbert Einstein, Presentation Speech (Speech). Nobel Prize award ceremony. Stockholm.

- next ref

- Einstein acknowledged Planck

- Ducharme, Stephen (2008). "Measuring Planck's Constant with LEDs". Materials Research Science and Engineering Center, University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- Ian Mills (27 September 2010). "Draft Chapter 2 for SI Brochure, following redefinitions of the base units" (PDF). BIPM. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- "에스비엔과학(주)". www.sbnscience.co.kr. Archived from the original on 2020-04-17. Retrieved 2020-02-08.

- Heymann, Y. (2021). Kelvin and the Age of the Universe. Amazon: Centorus Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 978-1838493646.