Philosophy of science

Philosophy of science is the part of philosophy that studies the sciences.

Philosophers who are interested in science study how knowledge is built up by scientists, and what makes science different from other activities. No doubt, modern science has advanced knowledge in a wide range of fields. How has it done this? To tackle this issue, a number of other issues also have to be tackled.

What makes science distinct?

Some people think that in earlier times, science was nothing but organized common sense. Thomas Henry Huxley thought this. However, during the twentieth century, science produced many ideas which were nothing like common sense, like general relativity. Then it was clear that science really was something different from common sense. But what was it? This is called the demarcation problem.

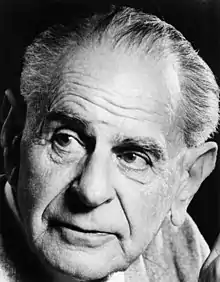

The demarcation problem refers to the distinction between science and non-science (like pseudoscience). Karl Popper called this the central question in the philosophy of science.[1] No solution to the problem has had full agreement among philosophers; some of them think the problem is insoluble or uninteresting.[2]

The logical positivists tried to base science on observation. In their view, truth was achieved by logic and observation. Non-science was non-observational and meaningless.[3]

Against that, Popper argued that the central property of science is falsifiability. All scientific claims can be proved false, at least in principle. If no such proof can be found despite sufficient effort, then the claim is likely true.[4] Popper's ideas were applauded by many scientists (like Peter Medawar). However, skeptics noticed that ideas were often not discarded when a prediction was refuted. The ideas were simply adjusted to take into account the new findings. It was clear from this that, although falsifiability was important, it could not be a simple way to distinguish science from non-science.

Other approaches were tried. One idea that science was a problem-solving process aimed at finding answers to questions.[5] Of course, many other fields try to answer questions and solve problems. Another approach was to define science as the search for objective truth. But objectivity is very hard to define, and whether science really is objective is open to question.

With biology, the situation wasn't the same as other parts of science. There were thousands of published observations, and Darwin showed that sense could be made of the observations. He used those ideas to prove evolution had taken place. In a natural history science (such as biology, geology or astronomy), one of the main jobs of science is to explain what has happened and what is seen. Obviously, explanations as well as observations and theories are part of the philosophy of science.

Theories and observations

Both theory and observations are part of science, and they are tied together in a kind of cycle. A clear example was the prediction of Einstein that a source of gravity (such as a star) would bend light passing nearby. An expedition was organised in 1919 to record the positions of stars around the Sun during a solar eclipse. It showed that the positions of the stars close to the Sun were changed slightly from their normal expected positions. The light passing close to the Sun was pulled towards the sun by gravitation. This seemed to prove Einstein's general theory of relativity, published in 1915. Many years later, the proof was shown to be wrong.[6] But by then other observations (of time dilation) showed that Einstein actually was right. Gravitational lensing proved that light was pulled towards the Sun.

The point here is that the observation and the theory were connected. The observation would not have been made but for the theory, and then the observation was convincing evidence in favour of the theory. The theory had passed a critical test. Since then, many more tests have been made of Einstein's ideas, and all have been consistent with his theory.

A “naive” conception of science

According to common sense,[7] science begins with observations: all scientific knowledge come from the facts of experience. Theories are produced by observation of these facts and are then tested by prediction.

Here is a schema of this idea of science that some philosophers call a naive conception of science:[7]

---> INDUCTION ---> LAWS AND THEORIES ---> DEDUCTION --->

| |

| |

| |

FACTS OF EXPERIENCE PREDICTIONS AND EXPLANATIONSFACTS OF EXPERIENCE

This naive conception is not held by many philosophers today. For one thing, it sees science as a one-way engine from 'facts' (what are they?) to theories and predictions. As shown by the Einstein example, where a theory led the other way round, the model does not fit much of science. In fact the relationship between the parts of a scientific philosophy are extremely complex.

Testing a prediction

According to Pierre Duhem and W.V. Quine, it is impossible to test a theory in isolation. For example, to test Newton's Law of Gravitation in our solar system, one needs information about the masses and positions of the Sun and all the planets. Famously, the failure to predict the orbit of Uranus in the 19th century did not lead to the rejection of Newton's Law. Instead, it lead to the rejection of the hypothesis that there are only seven planets in our solar system. The investigations that followed led to the discovery of an eighth planet, Neptune. If a test fails, something is wrong. But there is a problem in figuring out what that something is: a missing planet, badly calibrated test equipment, an unsuspected curvature of space, etc.

One consequence of the Duhem-Quine thesis is that any theory can be made compatible with any empirical observation by the addition of extra (ad hoc) hypotheses. This is why science uses Occam's Razor; hypotheses without justification are eliminated. This led Karl Popper, to reject naïve falsification in favor of 'survival of the fittest', or most falsifiable, of scientific theories. In Popper's view, any hypothesis that does not make testable predictions is simply not science. Such a hypothesis may be useful or valuable, but it cannot be said to be science. W.V. Quine thought that empirical data are not enough to make a judgment between theories. In this view, a theory can always be made to fit with the available empirical data. However, this does not necessarily imply that all theories are of equal value, because scientists often use guiding principles such as Occam's Razor.

One result of this view is that specialists in the philosophy of science stress the requirement that observations made for the purposes of science be restricted to intersubjective objects. That is, science is restricted to those areas where there is general agreement on the nature of the observations involved. It is comparatively easy to agree on observations of physical phenomena, harder to agree on observations of social or mental phenomena, and difficult in the extreme to reach agreement on matters of theology or ethics (and thus the latter remain outside the normal purview of science).

Other ideas

Critiques of scientific method

Is there any scientific method at all? Paul Feyerabend argued that no description of scientific method could possibly encompass all the approaches and methods used by scientists. Feyerabend objected to prescriptive scientific method on the grounds that any such method would stifle and cramp scientific progress. Feyerabend claimed, "the only principle that does not inhibit progress is: anything goes".[8]

Scientific revolutions

Thomas Kuhn denied that it is ever possible to isolate the hypothesis being tested from the influence of the theory in which the observations are grounded. He argued that observations always rely on a specific paradigm, and that it is not possible to evaluate competing paradigms independently. By "paradigm" he meant a consistent "portrait" of the world, one that involves no logical contradictions and that is consistent with observations made from the point of view of the paradigm. More than one such logically consistent construct can paint a usable likeness of the world, but there is no common ground from which to pit two against each other, theory against theory. Neither is a standard by which the other can be judged. Instead, the question is which "portrait" is judged by some set of people to promise the most useful in terms of scientific "puzzle solving".

For Kuhn, the choice of paradigm was sustained by, but not ultimately determined by, logical processes. The individual's choice between paradigms involves setting two or more "portraits" against the world and deciding which likeness is most promising. In the case of a general acceptance of one paradigm or another, Kuhn believed that it represented the consensus of the community of scientists. Acceptance or rejection of some paradigm is, he argued, a social process as much as a logical process. Kuhn's position, however, is not one of relativism.[9] According to Kuhn, a paradigm shift occurs when a number of observational anomalies (problems) in the old paradigm have made the new paradigm more useful. That is, the choice of a new paradigm is based on observations, even though those observations are made against the background of the old paradigm. A new paradigm is chosen because it does a better job of solving scientific problems than the old one.

The fact that observation is embedded in theory does not mean observations are irrelevant to science. Scientific understanding derives from observation, but the acceptance of scientific statements is dependent on the related theoretical paradigm as well as on observation. Of course, further testing may resolve differences of opinion.

Related pages

References

- Thornton, Stephen (Nov 13, 1997). "Karl Popper". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- Laudan, Larry (1983). "The demise of the demarcation problem". In Adolf Grünbaum; Robert Sonné Cohen; Larry Laudan (eds.). Physics, philosophy, and psychoanalysis: essays in honor of Adolf Grünbaum. Springer. ISBN 90-277-1533-5.

- Uebel, Thomas (2006). "Vienna Circle". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- Popper, Karl (2004) [First published 1959 by Hutchinson & Co.]. The logic of scientific discovery. London & New York: Routledge Classics. ISBN 0-415-27844-9.

- Bunge, Mario 1967. Scientific research. Volume 1: The search for system; volume 2: The search for truth. Springer-Verlag, Berlin & New York. Reprinted as Philosophy of science, Transaction, 1998.

- Gilmore FRS, Gerard; Tausch-Pebody, Gudrun (2022). "The 1919 eclipse results that verified general relativity and their later detractors: a story re-told". Notes and Records: The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science. 76: 155–180. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2020.0040. S2CID 225075861.

- Chalmers, Alan F. 1976/99. What is this thing called science? An assessment of the nature and status of science and its methods. Open University Press. ISBN 0-335-20109-1

- Feyerabend, Paul 1975. Against method: outline of an anarchistic theory of knowledge. ISBN 0-391-00381-X, ISBN 0-86091-222-1, ISBN 0-86091-481-X, ISBN 0-86091-646-4, ISBN 0-86091-934-X, ISBN 0-902308-91-2

- Kuhn T.S. 1970. The structure of scientific revolutions. 2nd ed, University of Chicago Press. p206 ISBN 0-226-45804-0