History of astronomy

The history of astronomy tells how civilizations thought about the sky they saw at night. It also discusses the beginnings of modern astronomy.

Early history

Babylonian astronomers viewed the sky as a celestial sphere, far above the Earth. This sphere had shiny stars on it. Like earlier astronomers, they organized and named the star patterns as constellations. They took special interest in the seven bright stars that did not stay in any particular constellation. These were the Star of the Day (Sun), the Star of the Night (Moon), and five planets. The stars and planets seemed to wander around the celestial sphere, in an area now called the Zodiac. The ancient astronomers carefully recorded the movements they saw.

Ancient Greece

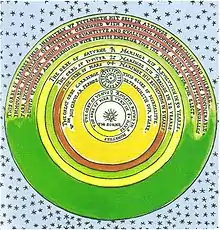

Greek philosophers, seeing the movement of heavenly bodies, developed models of the Universe based more on empirical evidence. The first model was proposed by Eudoxus of Cnidos. According to this model, space and time are infinite and eternal, the Earth is spherical and stationary, and all other matter is confined to rotating concentric spheres.

This model was brought into agreement with astronomical observations by Ptolemy of Alexandria, in the second century AD. His Syntaxis mathematica, known as the Almagest, was translated from Greek to Arabic, and from Arabic to Latin. It was printed in 1515, with another edition in 1528.[1]

However, not all Greek scientists accepted the geocentric (Earth-centered) model of the Universe. The Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus thought the center of the Universe was a "central fire" around which the Earth, Sun, Moon and Planets revolved in uniform circular motion.[2] The Greek astronomer Aristarchus of Samos was the first person to propose a heliocentric (Sun-centered) model of the universe. Though the original text has been lost, a reference in Archimedes' book The Sand Reckoner describes Aristarchus' heliocentric theory. Archimedes wrote: (translated into English)

You King Gelon are aware the 'Universe' is the name given by most astronomers to the sphere the center of which is the center of the Earth, while its radius is equal to the straight line between the center of the Sun and the center of the Earth. This is the common account as you have heard from astronomers. But Aristarchus has brought out a book consisting of certain hypotheses, wherein it appears, as a consequence of the assumptions made, that the universe is many times greater than the 'Universe' just mentioned. His hypotheses are that the fixed stars and the Sun remain unmoved, that the Earth revolves about the Sun on the circumference of a circle, the Sun lying in the middle of the orbit, and that the sphere of fixed stars, situated about the same center as the Sun, is so great that the circle in which he supposes the Earth to revolve bears such a proportion to the distance of the fixed stars as the center of the sphere bears to its surface.

So, Aristarchus thought the stars were very far away, and he said this was why there was no visible parallax. That is, no one saw movement of the stars relative to each other as the Earth moved around the Sun. Actually. the stars they saw were much farther away than was generally assumed in ancient times. Now we know that stellar parallax is only detectable with telescopes. The rejection of the heliocentric view was apparently quite strong, as the following passage from Plutarch suggests (On the apparent face in the orb of the Moon):

Cleanthes [a contemporary of Aristarchus and head of the Stoics] thought it was the duty of the Greeks to indict Aristarchus of Samos on the charge of impiety for putting in motion the Hearth of the universe [i.e. the Earth], . . . supposing the heaven to remain at rest and the earth to revolve in an oblique circle, while it rotates, at the same time, about its own axis.

The only other astronomer from antiquity known by name who supported Aristarchus' heliocentric model was Seleucus of Seleucia. He was a Babylonian astronomer a century after Aristarchus.[3][4][5] According to Plutarch, Seleucus was the first to prove the heliocentric system through reasoning, but it is not known what arguments he used. Seleucus' arguments for a heliocentric theory were probably related to the phenomenon of tides.[6] According to Strabo (1.1.9), Seleucus was the first to state that the tides are due to the attraction of the Moon, and that the height of the tides depends on the Moon's position relative to the Sun.[7]

Copernicus

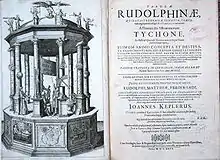

The geocentric model was accepted in the Western world for about two thousand years. In 1543 Copernicus revived Aristarchus’ theory. Copernicus said (again) that the sun was the center of the Solar System.

In the center rests the sun. For who would place this lamp of a very beautiful temple in another or better place than this wherefrom it can illuminate everything at the same time?

Copernicus Book 1, Chapter 10 of De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestrum, 1543

As noted by Copernicus himself, the idea that the Earth rotates (goes round on its axis) was very old, dating to Philolaus (c. 450 BC). A century before Copernicus, Nicholas of Cusa proposed that the Earth rotates on its axis. (This was in his book, On Learned Ignorance (1440).[8]

The first empirical evidence for the Earth's rotation on its axis, using the phenomenon of comets, was given by Tusi (1201–1274).[9][10]

Copernicus' heliocentric model allowed the stars to be placed uniformly through the (infinite) space surrounding the planets, as first proposed by Thomas Digges in his Perfit Description of the Caelestiall Orbes according to the most aunciente doctrine of the Pythagoreans, latelye revived by Copernicus and by Geometricall Demonstrations approved (1576).[8] Giordano Bruno accepted the idea that space was infinite and filled with solar systems similar to our own. n; for the publication of his various beliefs, he was burnt at the stake in Rome on 17 February 1600.[8]

This cosmology was accepted provisionally by Isaac Newton, Christiaan Huygens and later scientists,[8] but it had several paradoxes which were resolved only with general relativity. The first paradox was that it assumed that space and time were infinite, and that the stars in the universe had been burning forever; however, since stars are constantly radiating energy, a finite star seems inconsistent with the radiation of infinite energy. Secondly, Edmund Halley (1720) noted that an infinite space filled uniformly with stars would lead to the prediction that the nighttime sky would be as bright as the sun itself; this became known as Olbers' paradox in the 19th century.[8][11][12] Third, Newton himself showed that an infinite space uniformly filled with matter would cause infinite forces and instabilities crushing matter inwards inwards under gravity.[8] This instability was later clarified in 1902.[13]

18th century

As observations on the Solar System progressed, some basic facts appeared. All planets go round the Sun in the same direction, and their planes of revolution are very similar.[14] Likewise, most satellites go round planets in nearly the same planes. The planets revolve around their own axes in the same sense in which they orbit the Sun. These regularities cannot be a chance coincidence.

Many were at work trying to use the ideas of Newton and Kepler to explain the observational astronomy provided by the new, larger, telescopes.

A significant astronomical advance of the 18th century was the realization by Thomas Wright (1711–1786) that the "fixed stars" were not scattered at random, but concentrated in what we now call the "galactic plane", our view of the Milky Way.[15] What is even more remarkable is his idea that very faint nebulae, in which "no one star... can possibly be distinguished" might be extremely distant groups of the same kind.[15]p83/4

Kant (1724–1804), known today for his philosophy, made some important discoveries about the nature of the Earth's rotation. He showed the frictional resistance against tidal currents on the Earth's surface must cause a very gradual slowing of the earth's rotation. The days have grown longer as time has passed. Also, he laid out a nebular hypothesis,[16] in which he deduced that the Solar System formed from a large cloud of gas, a nebula. Following Wright, Kant also thought the Milky Way was a large disk of stars formed from a (much larger) spinning cloud of gas.

The greatest theoretician of the 18th century was Laplace (1749–1827), who worked on the mechanics of the planets and Solar System. His massive 5-volume work on the mechanics of the Solar System explained many of the regularities which observations had discovered.[17] Laplace made good use of another Frenchman's mathematics: Lagrange (1736–1813).

Laplace is also noteworthy for his nebular hypothesis of the evolution of the Solar System.[18] As it happens, the details of Laplace's theory do not quite work out for planetary systems, but they are the basis of how we understand stars condense out of a nebula.[19]

The 18th century was also a century of great observers. William Herschel (1738–1822), helped by his sister Caroline (1750–1848) built the biggest telescope of the day (40-foot), but did his best work on a 20-foot telescope. There were problems with the mirror of the large one. The discovery of Uranus put his career on the way: he got a salary of £200 a year as "King's Astronomer". He got a rough idea of where we are in the galaxy, and could see other spiral galaxies. He called them "island universes" like the Milky Way. Also he began to work out the motions of different stars. He discovered double stars, and published catalogues of them.[19]p113/120 Herschel's observations brought astronomy into the modern era.

Modern era

The modern era of physical cosmology began in 1917, when Albert Einstein first applied his general theory of relativity to model the structure and dynamics of the universe.[20]

Two great discoveries changed our picture of the Universe. Both were made by Edwin Hubble in the 1920s. Before then, it was thought that our galaxy, the Milky Way, was the whole universe. Hubble first showed that the Andromeda galaxy was a separate galaxy and similar. Many more galaxies were soon discovered. Later in the 1920s he showed that all distant galaxies were moving away from each other in a general expansion of the universe. He did this by discovering the red shift of spectroscopic light from distant galaxies. That does not apply to galaxies that are clustered together, such as Andromeda which, with our galaxy, is part of the Local Group in the Virgo Supercluster. Thus what move apart are clusters of galaxies kept together by local gravity.

References

- Stillwell, Margaret B. 1970. The awakening interest in science during the first century of printing. New York: Bibliographical Society of America, 30-32.

- Boyer C. A history of mathematics. Wiley, p54.

- Neugebauer, Otto E. 1945. The history of ancient astronomy: problems and methods. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 4 (1), p. 1–38.

- Sarton, George 1955. Chaldaean astronomy of the last three centuries B.C. Journal of the American Oriental Society 75 (3), pp. 166–173 [169]: "The heliocentrical astronomy invented by Aristarchos of Samos and still defended a century later by Seleucos the Babylonian".

- Wightman, William P.D. (1951, 1953), The growth of scientific ideas, Yale University Press p.38, where Wightman calls him Seleukos the Chaldean.

- Lucio Russo, Flussi e riflussi, Feltrinelli, Milano, 2003. ISBN 88-07-10349-4.

- Bartel Leendert van der Waerden 1987."The heliocentric system in Greek, Persian and Hindu astronomy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 500 (1): 525–545 [527]

- Misner C.W; Thorne K. & Wheeler J.A. 1973. Gravitation. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-0344-0

- Ragep, F. Jamil (2001a). "Tusi and Copernicus: the Earth's motion in context". Science in Context. 14 (1–2). Cambridge University Press: 145–63. doi:10.1017/S0269889701000060. S2CID 145372613.

- Ragep, F. Jamil (2001b). "Freeing astronomy from philosophy: an aspect of Islamic influence on science". Osiris, 2nd Series. 16 (Science in theistic contexts: cognitive dimensions): 49–64 & 66–71. doi:10.1086/649338. S2CID 142586786.

- Reprinted as Appendix I in Dickson FP (1969). The Bowl of Night: The physical universe and scientific thought. Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press. ISBN 978-0-2625-4003-2.

- Jean-Philippe de Cheseaux (1744). Traité de la Comète. Lausanne. pp. 223ff. Reprinted as Appendix II in Dickson, above ref.

- Jeans J.H. 1902. Philosophical Transactions Royal Society of London, Series A, 199, 1.

- If you model the way a planet goes round the Sun, it forms a plane in the shape of a ellipse.

- Wright. Thomas 1750. Theory of the Universe.

- Kant, Immanuel 1755. Allgemeine Naturgeschichte und Theorie des Himmels.

- Laplace, Pierre Simon 1799–1825, five volumes. Méchanique Céleste

- Laplace, Pierre Simon 1796. Exposition du Système du Monde.

- Wolfe A. 1938. A history of science, technology and philosophy in the eighteenth century. London: Allen & Unwin, p101.

- Einstein, A (1917). "Kosmologische Betrachtungen zur allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie". Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Sitzungsberichte. 1917 (part 1): 142–152.