Creation myth

A creation myth or creation story explains how the universe started, how the earth came to be, and why there are humans. Creation myths are usually part of religions and mythologies. Very often, creation myths say that humans were made by a god, spirit or other supreme being.

North America

Cherokee

In the beginning, there was just water. All the animals lived above it and the sky was overcrowded. They were all curious about what was beneath the water and one day Dayuni'si, the water beetle, volunteered to explore it. He explored the surface but could not find any solid ground. He explored below the surface to the bottom and all he found was mud which he brought back to the surface. After collecting the mud, it began to grow in size and spread outwards until it became the Earth as we know it.

Kiowa Apache

In the beginning nothing existed, darkness was all around. Suddenly from the darkness came a thin disc, one side yellow and the other side white, appearing suspended in midair. Within the disc sat a small bearded man, Creator, the One Who Lives Above. When he looked into the endless darkness, light appeared above. He looked down and it became a sea of light. To the east, he created yellow streaks of dawn. To the west, tints of many colors appeared everywhere. There were also clouds of different colors. He also created three other gods: a little girl, a sun god and a small boy. Then he created celestial phenomena, the winds, the tarantula, and the earth from the sweat of the four gods mixed together in the Creator's palms, from a small round, brown ball, not much larger than a bean. The world was expanded to its current size by the gods kicking the small brown ball. Creator told Wind to go inside the ball and to blow it up. The tarantula, who knew what to do, spun a black cord and, attaching it to the ball, crawled away fast to the east, pulling on the cord with all his strength. Tarantula repeated with a blue cord to the south, a yellow cord to the west, and a white cord to the north. With mighty pulls in each direction, the brown ball stretched to immeasurable size--it became the earth! No hills, mountains, or rivers were visible; only smooth, treeless, brown plains appeared. Then the Creator created the rest of the beings and features of the Earth.

Middle East

Judeo-Christian-Islamic account

In the Judeo-Christian-Islamic story, it is believed that an entity referred to as God created the universe in six days.

- First day: God creates light ("Let there be light!"[2]). The light is divided from the darkness, and "day" and "night" are named.[3]

- Second day: God makes the sky over the earth (the atmosphere), dividing the waters above from the waters below.[4]

- Third day: God commands the waters on earth to be gathered together in one place (ocean), and dry land to appear. "Earth" and "sea" are named. God commands the earth to bring forth grass, plants, and fruit-bearing trees.[5]

- Fourth day: God creates lights in the sky to separate light from darkness and to mark days, seasons and years. Two great lights are made (the Sun and Moon, though not named), and the stars.[6]

- Fifth day: God commands the sea to be filled with "living creatures", and every kind of bird, and commands them to be fruitful and multiply.[7]

- Sixth day: God commands the land produce all kinds of animals. He makes wild beasts, livestock and reptiles. He then creates the first human (Adam). People are told to "be fruitful, and multiply, and fill the earth, and subdue it." Humans and animals are given plants to eat. Then God calls his creation "very good."[8]

- Seventh day: On the seventh day God rested.[9]

Christians that believe God created the Universe in exactly the way described in the Bible are called creationists. Other Christians think that the biblical creation story has fundamental truths and messages, but should not be taken literally.

In other cultures/religions

Many cultures have stories describing the origin of the world, which may be roughly grouped into common types. In one type of story, the world is born from a world egg; such stories include the Finnish epic poem Kalevala, the Chinese story of Pangu or the Indian Brahmanda Purana. In related stories, the creation is caused by a single entity emanating or producing something by his or herself, as in the Tibetan Buddhism concept of Adi-Buddha, the ancient Greek story of Gaia (Mother Earth), the Aztec goddess Coatlicue myth, the ancient Egyptian god Atum story, or the Genesis creation myth. In another type of story, the world is created from the union of male and female deities, as in the Maori story of Rangi and Papa. In other stories, the Universe is created by crafting it from pre-existing materials, such as the corpse of a dead god — as from Tiamat in the Babylonian epic Enuma Elish or from the giant Ymir in Norse mythology – or from chaotic materials, as in Izanagi and Izanami in Japanese mythology. In another type of story, the world is created by the command of a divinity, as in the ancient Egyptian story of Ptah or the Genesis creation myth as a part of Jewish and Christian mythology. In other stories, the universe emanates from fundamental principles, such as Brahman and Prakrti, or the yin and yang of the Tao.

Although Heraclitus argued for eternal change, his quasi-contemporary Parmenides made the radical suggestion that all change is an illusion, that the true underlying reality is eternally unchanging and of a single nature. Parmenides denoted this reality as το εν (The One). Parmenides' theory seemed implausible to many Greeks, but his student Zeno of Elea challenged them with several famous paradoxes. Aristotle resolved these paradoxes by developing the notion of an infinitely divisible continuum, and applying it to space and time.

The Indian philosopher Kanada, founder of the Vaisheshika school, developed a theory of atomism and proposed that light and heat were varieties of the same substance.[10] In the 5th century AD, the Buddhist atomist philosopher Dignāga proposed atoms to be point-sized, durationless, and made of energy. They denied the existence of substantial matter and proposed that movement consisted of momentary flashes of a stream of energy.[11]

The theory of temporal finitism was inspired by the doctrine of creation shared by the three Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Christianity and Islam. The Christian philosopher, John Philoponus, presented the philosophical arguments against the ancient Greek notion of an infinite past. Philoponus' arguments against an infinite past were used by the early Muslim philosopher, Al-Kindi (Alkindus); the Jewish philosopher, Saadia Gaon (Saadia ben Joseph); and the Muslim theologian, Al-Ghazali (Algazel). They employed two logical arguments against an infinite past, the first being the "argument from the impossibility of the existence of an actual infinite", which states:[12]

- "An actual infinite amount cannot exist."

- "An infinite temporal regress of events is an actual infinite."

- " An infinite temporal regress of events cannot exist."

The second argument, the "argument from the impossibility of completing an actual infinite by successive addition", states:[12]

- "An actual infinite cannot be completed by successive addition."

- "The temporal series of past events has been completed by successive addition."

- " The temporal series of past events cannot be an actual infinite."

Both arguments were adopted by later Christian philosophers and theologians, and the second argument in particular became more famous after it was adopted by Immanuel Kant in his thesis of the first antinomy concerning time.[12]

Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209) criticized the idea of the Earth's centrality within the universe. In the context of his commentary on the Qur'anic verse, "All praise belongs to God, Lord of the Worlds," he raises the question of whether the term "worlds" in this verse refers to "multiple worlds within this single universe or cosmos, or to many other universes or a multiverse beyond this known universe." He rejected the Aristotelian and Avicennian notions of a single universe revolving around a single world, and instead argued that there are more than "a thousand thousand worlds (alfa alfi 'awalim) beyond this world such that each one of those worlds be bigger and more massive than this world as well as having the like of what this world has."[13] He argued that there exists an infinite outer space beyond the known world,[14] and that God has the power to fill the vacuum with an infinite number of universes.[15]

Other websites

References

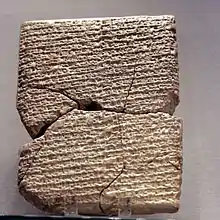

- An interpretation of the creation narrative from the first book of the Torah (commonly known as the Book of Genesis), painting from the collections Archived 2013-04-16 at Archive.today of the Jewish Museum (New York)

- Genesis 1:3

- Genesis 1:5

- Genesis 1:6

- Genesis 1:9–11

- Genesis 1:14

- Genesis 1:20–23

- Genesis 1:24–31

- Genesis 2:2

- Will Durant, Our Oriental Heritage:

"Two systems of Hindu thought propound physical theories suggestively similar to those of Greece. Kanada, founder of the Vaisheshika philosophy, held that the world was composed of atoms as many in kind as the various elements. The Jains were more like Democritus by teaching that all atoms were of the same kind, producing different effects by diverse modes of combinations. Kanada believed light and heat to be varieties of the same substance; Udayana taught that all heat comes from the sun; and Vachaspati, like Newton, interpreted light as composed of minute particles emitted by substances and striking the eye."

- F. Th. Stcherbatsky (1930, 1962), Buddhist Logic, Volume 1, p.19, Dover, New York:

"The Buddhists denied the existence of substantial matter altogether. Movement consists for them of moments, it is a staccato movement, momentary flashes of a stream of energy... "Everything is evanescent“,... says the Buddhist, because there is no stuff... Both systems [Sānkhya, and later Indian Buddhism] push the analysis of Existence up to its minutest, last elements which are imagined as absolute qualities, or things possessing only one unique quality. They are called “qualities” (guna-dharma) in both systems in the sense of absolute qualities, a kind of atomic, or intra-atomic, energies of which the empirical things are composed. Both systems, therefore, agree in denying the objective reality of the categories of Substance and Quality,... and of the relation of Inference uniting them. There is in Sānkhya philosophy no separate existence of qualities. What we call quality is but a particular manifestation of a subtle entity. To every new unit of quality is related a subtle quantum of matter which is called guna “quality”, but represents a subtle substantive entity. The same applies to early Buddhism where all qualities are substantive... or, more precisely, dynamic entities, although they are also called dharmas ('qualities')."

- Craig, William Lane (June 1979). "Whitrow and Popper on the Impossibility of an Infinite Past". The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. 30 (2): 165–170 [165–6]. doi:10.1093/bjps/30.2.165.

- Adi Setia (2004), "Fakhr Al-Din Al-Razi on Physics and the Nature of the Physical World: A Preliminary Survey", Islam & Science, 2, archived from the original on 2012-07-10, retrieved 2010-03-02

- Muammer İskenderoğlu (2002), Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī and Thomas Aquinas on the question of the eternity of the world, Brill Publishers, p. 79, ISBN 9004124802

- John Cooper (1998), "al-Razi, Fakhr al-Din (1149-1209)", Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Routledge, retrieved 2010-03-07