Crab

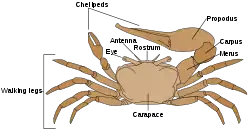

Crabs are a form of decapods (having eight walking legs and two grasping claws), along with lobsters, crayfish and shrimps. Crabs form an order within the decapods, called the Brachyura. Their short body is covered by a thick exoskeleton.

| Brachyura Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Grey swimming crab Liocarcinus vernalis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Order: | Decapoda |

| Suborder: | Pleocyemata |

| (unranked): | Reptantia |

| Infraorder: | Brachyura Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Sections and subsections[1] | |

| |

They are an extremely successful group, found all over the world. They are basically heavily armored shell-breakers. Most crabs live in sea-water, but there are some who live in fresh water, and some who live on land. The smallest are the size of a pea; the largest (the Japanese spider crab) grows to a leg span of 4 metres.[2] About 7,000 species are known.[3]

Structure and life-style

Body

Crabs have short tails. A crab's tail and reduced abdomen is entirely hidden under the thorax. It is folded under its body, and may not be visible at all unless the crab is turned over. Usually they have a very hard exoskeleton. This means they are well protected against predators. Crabs are armed with a single pair of claws. Crabs can be found in all oceans. Some crabs also live in fresh water, or live completely on land.

Pincers

The pincers (claws) of crabs are their most important weapons. They have at least three functions. The pincers' role in eating is to seize and subdue the prey. If the food is a shellfish (mollusc), then the pincers can exert force to open or break the mollusks shell. Pincers are also used in fighting between males, and for signalling to other crabs.

Crabs as food

Crabs are prepared and eaten all over the world. Some species are eaten whole, including the shell, such as soft-shell crab; with other species just the claws and/or legs are eaten. In some regions spices improve the culinary experience. In Asia, Masala Crab and Chilli crab are examples of heavily spiced dishes. In the United States state of Maryland, blue crab is often eaten with Old Bay Seasoning.

For the British dish Cromer crab, the meat is extracted and placed inside the hard shell. One American way to prepare crab meat is by extracting it and adding a flour mix, creating a crab cake. Crabs are also used in bisque, a French soup.

Evolution

True crabs appear in the fossil record in the Lower Jurassic. They are part of the 'Mesozoic marine revolution', in which a number of sea-floor predators evolved.[6][7][8]

Tailpiece

The closest relatives of the crabs are anomurans, a crustacean group which includes animals such as hermit crabs, king crabs and squat lobsters. They look a lot like crabs and many have the word 'crab' in their name, but are not true crabs. Anomurans can be told apart by the number of legs: crabs have eight legs, along with two claws or pincers, while the last pair of an anomuran's legs is hidden inside the shell, so that only six are visible.

References

- Sammy De Grave; N. Dean Pentcheff; et al. (2009). "A classification of living and fossil genera of decapod crustaceans" (PDF). Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. Suppl. 21: 1–109. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-06.

- "Size of crabs". Archived from the original on 2016-03-06. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- Walters, Martin & Johnson, Jinny. 2007. The World of Animals. Bath, Somerset: Parragon.

- Kennish, R. (1996). "Diet composition influeces the fitness of the herbivorous crab Grapsus albolineatus". Oecologia. 105 (1): 22–29. Bibcode:1996Oecol.105...22K. doi:10.1007/BF00328787. PMID 28307118. S2CID 24146814.

- Buck T.L.; et al. (2003). "Diet choice in an omnivorous salt-marsh crab: different food types, body size, and habitat complexity". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 292 (1): 103–116. doi:10.1016/S0022-0981(03)00146-1. Archived from the original on 2009-02-06. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- Vermeij G.J. (1977). "The Mesozoic marine revolution; evidence from snails, predators and grazers". Paleobiology. 3 (3): 245–258. doi:10.1017/S0094837300005352. JSTOR 2400374. S2CID 54742050. Retrieved 2008-05-13.

- Stanley S.M. (2008). "Predation defeats competition on the seafloor". Paleobiology. 34: 1–21. doi:10.1666/07026.1. S2CID 83713101.

- Stanley SM (1974). "What has happened to the articulate brachiopods?". GSA Abstracts with Programs. 8: 966–967.