Cnidaria

Cnidaria is a phylum with about 11,000 species of animals.[1] All of them are simple and aquatic, and most of them live in the sea. Some are colonial, composed of zooids which may be clones. Cnidarian zooids may take the form of polyps or medusae at different phases of their life.

| Cnidaria | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| East Coast sea nettle Chrysaora quinquecirrha (?) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Subphylum: | |

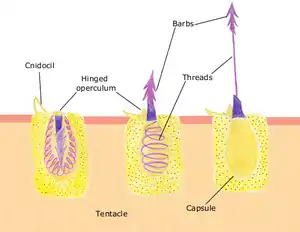

Cnidaria take their name from special cells which have organelles that sting: the nematocysts. This device is largely responsible for their success: it is their main specialised and distinctive cell type.[2]

Pronunciation

The word Cnidaria is spoken without the initial "C", and with a long "i". So it sounds like "Naidaria". In a similar way, the term Ctenophore is pronounced as "Teenophore". Originally, a Greek kappa was in front of the words, and it was pronounced. The name comes from Greek language knidi, "nettle", thus mening "nettle-like animals" as all cnidarians have stinging cells like nettles.

Subdivisions

There are five classes in the group.[1] Jellyfish occur in four of the classes.

- Subphylum and class Anthozoa: the sea anemones and corals.

- Subphylum Medusozoa: the jellyfish [3]

- Class Scyphozoa: the 'true' jellyfish.

- Class Cubozoa: the box jellies.

- Class Hydrozoa: the hydroids: (Hydra; Portuguese man o' war).

- Class Staurozoa: the stalked jellyfish.

Unranked, but now known to be cnidarians, is the parasitic group Myxozoa.

Basic body forms

Adult cnidarians are usually either free-swimming medusae or sessile polyps. Many alternate between the two forms. Both forms are radially symmetrical, like a wheel and a tube respectively.

Most have fringes of tentacles equipped with cnidocytes around their edges. Medusae usually have an inner ring of tentacles around their mouth. Some hydroids may be colonies of zooids which serve different purposes: defence, reproduction and catching prey. The mesoglea of medusae is a thick and springy jelly, so it returns to its original shape after muscles around the edge have contracted. This makes a sort of jet propulsion.

Skeletons

In medusae the only supporting structure is the jelly inside their cell layers. Hydra and most sea anemones close their mouths when they are not feeding, and the water in the digestive cavity then acts as a kind of skeleton, rather like a water-filled balloon. Other polyps such as Tubularia use columns of water-filled cells for support. Sea pens stiffen the mesogleal jelly with calcium carbonate spicules and tough fibrous proteins, rather like sponges.

In some colonial polyps, a chitinous periderm gives support and some protection to the connecting sections and to the lower parts of individual polyps. Stony corals secrete massive calcium carbonate exoskeletons. A few polyps collect materials such as sand grains and shell fragments, which they attach to their outsides. Some colonial sea anemones stiffen the mesoglea with sediment particles.

Fossil record

There is a long fossil record for the corals, and soft-bodied forms appear in some exceptional strata. Some are believed to be among the Ediacaran biota.[4]

References

- Daly M. et al 2007. The phylum Cnidaria: a review of phylogenetic patterns and diversity 300 years after Linnaeus. Zootaxa, 1668: 127–182, Wellington.

- Ruppert E.E; Fox R.S. & Barnes R.D. 2004. Invertebrate Zoology. Brooks/Cole 7th ed. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1

- Classes in Medusozoa based on "The Taxonomicon - Taxon: Subphylum Medusozoa". Universal Taxonomic Services. Archived from the original on 2009-03-11. Retrieved 2009-01-26.

- Waggoner B. & Collins A.G. (2004). "Reductio ad absurdum: testing the evolutionary relationships of Ediacaran and Paleozoic problematic fossils using molecular divergence dates". Journal of Paleontology. 78: 51–61. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2004)078<0051:RAATTE>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 8556856.