| Zaamslag Castle | |

|---|---|

Kasteel van Zaamslag (Torenberg) | |

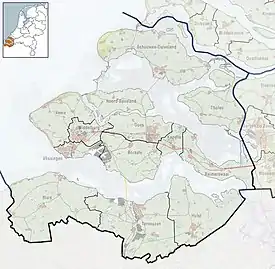

| Zaamslag, Zeeland the Netherlands | |

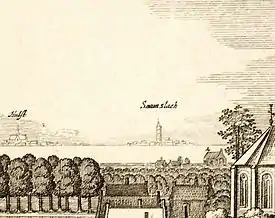

Zaamslag with the castle tower in about 1660 | |

Zaamslag Castle | |

| Coordinates | 51°18′39″N 3°54′57″E / 51.310833°N 3.915833°E |

| Type | Motte-and-bailey castle |

| Site information | |

| Open to the public | No |

| Condition | Terrain with Motte and part of the moats |

| Site history | |

| Built | 12th century |

| Materials | brick, stone |

Zaamslag Castle was a Motte-and-bailey castle in Zeelandic Flanders, the motte (artificial hill) remains. It is called Torenberg.

Location

Zaamslag Island

When Zaamslag Castle was built in the 12th century, its location was part of the County of Flanders. The Western Scheldt or Honte was a sea arm that was not yet fully connected to the Scheldt, which flowed to the North Sea via the Eastern Scheldt.

The coast of Flanders consisted of Fens with sandy ridges in between. On some of these ridges near Ghent's north and northeast in the year 1000, a population began to grow. One of these was Zaamslag's height, which can still be seen in the village. Aendijcke and De Kraag were the others. After that, a polder was created. As a result, Zaamslag Island was made. It had three villages. Zaamslag was the largest, Othene probably the oldest, and there was Aendijcke. Ghenderdijcke and Campen were hamlets.[1]

The island measured about 8 kilometers from east to west, and 9 kilometers from north to south.[2] By 1335 Zaamslag had been connected to mainland Flanders, and was no longer an island.[2]

Destruction of Zaamslag

Between 1584 and 1586 all the dikes in the area were destroyed by the Dutch Republic in order to keep control of the Scheldt. This did not immediately destroy Zaamslag village and its castle, because both were above Amsterdam Ordnance Datum. However, neglect by abandonment would have the same effect.[3]

In 1649-1650 Zaamslag was finally reclaimed.[3] A new village was built on the same place.[4] This was probably easier, because the area had meanwhile been used to acquire building materials. Many buildings were constructed using brick from the churches and other buildings in Zaamslag and the surrounding area. There was even official permission to do this.

Castle Characteristics

The motte / main castle

Zaamslag Castle was a Motte-and-bailey castle. The motte still exists, and is called Torenberg. Its top is still 3.3 m above Amsterdam Ordnance Datum (AOD). Its diameter is about 48 m. Around most of the Torenberg is a depression at about 0.7 m above AOD, which can be identified as the moat, which is in turn about 0.5 m below the surrounding field.[5]

The main castle has never been excavated. The only reliable source about the main castle / motte is the 1569 map by Horenbault. It depicts the castle as a round walled site with a moat, some towers on the wall, and a central keep. The outer bailey was not depicted.[6]

During excavations, a pile from the bridge was found that was dated to having been cut between 1089 and 1103.[7] Earlier, the dating had been misread to 1193.[8][9] This mistake did not matter much, because in both cases, it could be assumed that the main castle or Motte started as a wooden tower on an artificial hill. It is not known whether there was a preceding lower version of the c. 1200 motte. A phenomenon that was observed at many other mottes.[6]

In the second half of the 13th century, the main castle became a brick structure.[10]

Later, ever more parts were rebuilt in brick. The overall form nevertheless remained the same. At the motte, the form resembles that of the Burcht of Voorne.

The outer bailey

The outer bailey was investigated in 1987. It measured approximately 75 by 50 meters, with a surrounding moat of 15 to 25 meters wide. The moat on the site of the village was investigated most thoroughly. Here the wood dated to having been cut between 1089 and 1103 (as earliest possible date) had been used as a pile for a bridge.[7][9] Marks on the wood showed that it was first used for a different purpose. It may be assumed that it came from a construction on the motte.[8]

In the early 13th century, the outer bailey probably had a wooden farm and a wooden bridge. From findings, it is known that the inhabitants held cows, pigs, sheep and chicken. From the clipped wings of geese, we can assume that chicken and geese were walking freely on the terrain.[8]

During the second half of the 13th century, the level of the outer bailey was raised by about 0.75 m. The bridgehead of the village bridge on the island side was rebuilt in brick. [6] A supposed gatehouse was built in brick of 31 * 16 * 8 cm. A sewer that was wide enough to enter was built from the same brick. No ring wall was found on the outer bailey.[10]

Somewhat later, the gate was rebuilt to a tower with a square floor plan. The brick used measured 29 * 13 * 7 cm. Instead of the bridge, a double wall was constructed, that kept the water of the moat out of the entrance to the outer bailey. Somewhat later, these walls were clad in limestone (ledesteen) from +0.7 to +2.0 m above AOD.[10]

The dreefmuren were two parallel walls that ran from the walls in the moat in the direction of the village. The brick used was the smallest found during the excavations: 27 * 13 * 6.5 cm. The excavations showed much damage from flooding to the dreefmuren. This took the form of a marine sediment layer on top of it.[11]

Some foundations on the outer bailey were situated in line with the dreefmuren. During the 14th and 15th century many improvements were made at the castle.[11]

The tower on the outer bailey

An eyewitness account of the tower on the motte was given by Jona van Middelhoven after its destruction. He had seen it in his youth. He described it as a square, 20 m wide tower. The basement was vaulted, and had served as a prison. On top there were embrasures, and it had also served as a beacon , visible from Vlissingen. [12]

History

The lordship Zaamslag

The lords of Zaamslag appear in the late 12th century. In the 14th century a Robert van Zaamslag was mentioned.[13] In 1385 the Lord of Borselen is mentioned as having improved the fortification of Zaamslag Castle. In the mid-15th century, it was heavily damaged during the war between Philip the Good and Ghent.[14]

Destruction of the castle

During the Eighty Years' War, Zaamslag was destroyed when the dikes were cut from 1584 to 1586. One can assume that the dreefmuren were immediately destroyed during the subsequent flooding. For the outer bailey and main castle, the story differed. Both were above AOD, and so was the village.

Nevertheless, destruction happened in the subsequent years. In 1587 the government of Zeeland gave official permission to loot brick at: vande kercke van Saeftinghe, Samslach, thuijs van Bouweloo ende het Tempel huijs..[15] While it's not clear whether this refers to the castle, instead of the church of Zaamslag, it reflected a trend. Still in May 1591, about 15 soldiers garrisoned the castle.(thuys van Zaemslacht)

Destruction of the tower on the motte

In 1593 the Zeeland government ordered that the tower of Zaamslag should not be destroyed.[16] However, if no maintenance was done, this only delayed its disappearance. In 1697 the tower, located behind the house 'Torenhoeve', was finally demolished.[17]

Current situation

After the lands around Zaamslag had been reclaimed, a farm with a large barn and carriage house was erected. In 1970, the motte called Torenberg became a national monument. It was supposed that the buildings on the outer bailey protected that area, but this proved a mistake.[18] When in 1983 a storm inflicted heavy damage on the monumental barn and carriage house, these were demolished. Terneuzen municipality then grabbed the chance to construct houses in the area.[18] Protests by the local history society, and more importantly, the Rijksdienst voor het Oudheidkundig Bodemonderzoek (ROB, National Archaeological Service) could not to rescue the terrain.[19]

In the Summer of 1987 the National Archaeological Service was allowed to make some hasty excavations.[20] The results were surprising, but they did not stop the housing project. The foundations that were found were removed.[21] Some finds went to the Schelpenmuseum in Zaamslag, which is private local museum dedicated to marine life and local archaeology.

In 2014 a depiction of the castle entrance dreefmuren was placed on the corner of Plein and Voorburch streets.

References

- Van der Baan, Joost (1857), "Zaamslag in zijn vroegeren toestand beschouwd", Cadsandria, pp. 39–55

- Van der Baan, Joost (1859), Geschiedkundige beschouwing van Zaamslag, van de vroegste tijden tot op heden

- Briels, I.R.P.M. (2016), De Torenberg te Zaamslag – een uitgebreid archeologisch bureauonderzoek (PDF), RAAP

- Van Dierendonck, Robert M. (2016), Nieuwe wijn uit oude zak(k)en, Evaluatie van de Provinciale Onderzoeksagenda Archeologie Zeeland (POAZ) 2009-2015 (PDF), Stichting Cultureel Erfgoed Zeeland

- Van Heeringen, R.M. (1988), Archeologische Kroniek van Zeeland over 1987, pp. 129–147

- Van Heeringen, R.M. (1989), "Het Kasteel van Zaamslag (II), archeologisch onderzoek op het voorterrein van de "Torenberg"", Zeeuws Tijdschrift, pp. 209–214

- De Kraker, A.M.J. (1989), "Het Kasteel van Zaamslag (I), De "Torenberg" als middelpunt van de ambachtsheerlijkheid Zaamslag", Zeeuws Tijdschrift, pp. 189–196

- Lensen, R.J.H. (2013), De uithof van Othene. Een archeologische zoektocht op het Zaamslags Eiland (1220-1584), Stichting Zaamslag 850 Jaar

- Verhoeckx, Maartje; Kuipers, J.J.B. (2013), "Torenberg / Kasteel van Zaamslag", Kastelenlexicon, Nederlandse Kastelen Stichting (NKS)

Notes

- ↑ Lensen 2013, p. 17.

- 1 2 Lensen 2013, p. 18.

- 1 2 Lensen 2013, p. 26.

- ↑ Lensen 2013, p. 28.

- ↑ Briels 2016, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 Van Heeringen 1989, p. 211.

- 1 2 Van Dierendonck 2016, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 Van Heeringen 1989, p. 210.

- 1 2 Briels 2016, p. 43.

- 1 2 3 Van Heeringen 1989, p. 212.

- 1 2 Van Heeringen 1989, p. 213.

- ↑ Van der Baan 1857, p. 47.

- ↑ De Kraker 1989, p. 189.

- ↑ De Kraker 1989, p. 190.

- ↑ De Kraker 1989, p. 193.

- ↑ De Kraker 1989, p. 194.

- ↑ Van der Baan 1859, p. 95.

- 1 2 Van Heeringen 1989, p. 209.

- ↑ "Torenberg moet bewaard blijven". De Stem. 21 November 1985.

- ↑ Van Heeringen 1988, p. 143.

- ↑ Briels 2016, p. 52.