.jpg.webp)

A yellowcake boomtown also known as a uranium boomtown, is a town or community that rapidly increases in population and economics due to the discovery of uranium ore-bearing minerals, and the development of uranium mining, milling or enrichment activities. After these activities cease, the town "goes bust" and the population decreases rapidly.[1][2][3]

Yellowcake (uranium oxide) is partially refined uranium ore, called so because of its bright yellow color.[4]

Jeffrey City, Wyoming is considered a yellowcake boomtown whose "boom" began in 1957, and by 1988 the town had gone "bust" with only a few residents left.[4]

Uranium "gold rush"

During the Cold War era in the mid-1950s, uranium became a valuable commodity.[1][5] The sense of urgency to find and extract uranium and uranium-bearing ores was fueled by the rapidly developing nuclear weapons stockpile in response to the nuclear-arms race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. This uranium mining boom was considered by prospectors, miners and investors as the new "gold rush".[5]

North America

Examples of yellowcake boomtowns are Grants, New Mexico; Moab, Utah; Jeffrey City, Wyoming; and Uravan, Colorado, although there are many others throughout the American West, and in other countries.[1][6]

Like many yellowcake boomtowns, Jeffrey City, Wyoming grew rapidly during the Cold War era from a "trailer town" to a bustling community after the development of uranium mining and processing facilities there.[1] By the 1960s the U.S. stockpile of nuclear weapons leveled off and the need for enriched uranium reached a plateau. With the development of nuclear energy in the 1970s the demand for yellowcake increased again. By the early 1980s, Jeffrey City had reached its apex (population 4,500);[7] the mine shut down in 1982 and by 1988 the town had "gone bust" after the uranium mill had been decommissioned.[4] The town lost 95% of its population,[8] and in 2010 only 58 people lived there.[7]

Moab, Utah, known as the "Uranium Capital of the World", is also considered a yellowcake boomtown, although its population has sustained due to tourism at the nearby Arches National Park. The boom was initiated in 1952 by Charlie Steen's discovery of uranium and vanadium ore.[9][1] Within a few years following Steen's discovery, the population of Moab grew from 1,200 to 6,500.[10]

In 1950, Navajo rancher Paddy Martinez discovered uranium ore near Grants, New Mexico. The small village of Grants grew to become the "center of the largest uranium rush of the 1950s". Five processing mills were built to enrich the ore into yellowcake. Like Moab, the town of Grants is also referred to as the "Uranium Capital of the World".[1] After the discovery of uranium in 1950, its population grew from 2,200 to 50,000 within a few months.[11]

The uranium mining town Uravan, Colorado, is now an abandoned ghost town and Superfund site.[12] During the Cold War era Uravan had a population of 800; the town had a school, medical facilities, recreational centers and stores. It now has a population of zero, and all of the buildings have been demolished.[1] As part of the clean-up efforts, the town has been completely buried beneath sand and dirt; any visitors or "atomic tourists" are prohibited from exploring the area, or walking the grounds of the former town.[13]

In Edgemont, South Dakota the yellowcake goldrush started in 1951 when the town became "dominated by a massive, Chicago-based holding company," the Susquehanna Corporation, along with two subsidiary companies, Susquehanna-Western and Mines Development. In 1955, the Atomic Energy Commission chose the Colorado-based company Mines Development to build a uranium mill in Edgemont.[5] Workers were underpaid and not issued appropriate protective gear. In 1960, Mines Development was issued citations by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission for failure to conduct required airborne radioactivity tests in areas used by employees. In the 1970s, Susquehanna Corporation sold its interests in the operation and left behind numerous abandoned uranium mines and associated radioactive mill tailings. Because no reclamation laws existed at the time requiring companies to clean up their environmental messes, abandoned mines remain in the Edgemont area to this day.[14] The short-term economic boost from uranium mining left behind a community that suffered from health and environmental impacts for decades afterwards.[5] In the 1980s the radioactive mill buildings and contaminated homes were demolished, however the abandoned open-pit uranium mines still exist.[15]

Australia

In Australia, Radium Hill had a population on 1,100 in the 1950s during the uranium mining boom; it now is a ghost town with residual hazards.[16][17]

Other geographic areas

Other yellowcake boomtowns include Elliot Lake, Ontario, Canada;[18] Dominionville, South Africa;[19] Uranium City, Saskatchewan, Canada;[20] Yangiobod, Uzbekistan[21] among others.[22]

Gallery

"Caution- Radioactive Materials" sign at Uravan townsite, Colorado

"Caution- Radioactive Materials" sign at Uravan townsite, Colorado Former townsite of Uravan, Colorado in 2008

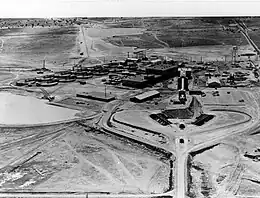

Former townsite of Uravan, Colorado in 2008 Kerr-McGee Uranium mill, Grants NM

Kerr-McGee Uranium mill, Grants NM

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Admundson, Michael A. (2002). Yellowcake Towns: Uranium Mining Communities in the American West. Boulder, CO: University of Colorado Press. ISBN 0-87081-765-5. JSTOR j.ctt2tv5vc. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ↑ Keeling, A. (2010). "Born in an atomic test tube': landscapes of cyclonic development at Uranium City, Saskatchewan" (PDF). Canadian Geographer. 54 (2): 228–252. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0064.2009.00294.x.

- ↑ Goss, Addie (8 November 2008). "A New Boom? Mining Town Doesn't Hold Its Breath". NPR News. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- 1 2 3 Anderson, Chamois L.; Van Pelt, Lori. "Wyoming's Uranium Drama: Risks, Rewards and Remorse". Wyoming History. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Tupper, Seth (1 November 2015). "Radioactive Legacy, Part 1 of a Journal Special Report". Rapid City Journal. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ↑ Mauk, Ben (October 2017). "States of Decay". Harper's Magazine. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- 1 2 "Jeffrey City Ghost Town: This mining town boomed in the Atomic Age when uranium was gold, only to be abandoned when the industry collapsed". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ↑ Admunson, Michael A. (Winter 1995). "Home on the Range No More: The boom and bust of a Wyoming uranium mining town". Western Historical Quarterly. 26. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ↑ Stiles (1 June 2015). "Charlie Steen's Mi Vida & Boom Town Moab… by Maxine Newell". The Canyon County Zephyr. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ↑ "Uranium Boom: How did Moab become "Boomtown"?". Moab Museum. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ↑ "Paddy Martinez (1881-1969)". National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ↑ "Uravan Uranium". Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 2004-09-08. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ↑ "Uravan: Only a few signs remain of the buried Colorado mining town that supplied the uranium for the first atomic bomb". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ↑ Tupper, Seth (1 November 2015). "Radioactive Legacy, Part 2 of a Journal special report: Danger in the mines and mill". Rapid City Journal. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ↑ Tupper, Seth (1 November 2015). "Radioactive Legacy, Part 3 of a Journal special report: The uranium boom goes bust". Rapid City Journal. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ↑ "Radium Hill Mine". Government of South Australia. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ↑ Lottermoser, B.G.; Ashley, P.M. (2006). "Physical dispersion of radioactive mine waste at the rehabilitated Radium Hill uranium mine site, South Australia". Australian Journal of Earth Sciences. 53 (3): 485–499. Bibcode:2006AuJES..53..485L. doi:10.1080/08120090600632383. S2CID 53481984.

- ↑ Bucksar, Richard G. (1962). "Elliot Lake, Ontario: Problems of A Modern "Boom-Town"". Journal of Geography. 61 (3): 119–125. doi:10.1080/00221346208982122.

- ↑ De Wet, Phillip (4 December 2014). "Uranium mining town hopes long turned to dust". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ↑ Sandberg, Patricia (2016). Sun Dogs and Yellowcake. Crackingstone Press. ISBN 9780995202306.

- ↑ "Glitterati". Eurasianet. Urasianet. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ↑ van Wyck, Peter C. (2010). The Highway of the Atom. McGill-Queens University Press. ISBN 978-0773537835. JSTOR j.ctt80mfz.