Xwedodah (Persian: خویدوده; khwēdōdah; Avestan: xᵛae¯tuuadaθa) is a spiritually-influenced style of consanguine marriage assumed to have been historically practiced in Zoroastrianism before the Muslim conquest of Persia.[1] Such marriages are recorded as having been inspired by Zoroastrian cosmogony and considered pious. It was a high act of worship in Zoroastrianism, and there were punishments for not performing it.[2][3] This form of direct familial incest marriage allowed Zoroastrians to marry their sisters, daughters, granddaughters, and their own mothers to take as wives.[4] Xwedodah was widely practiced by royalty and nobility, and possibly clergy, but it is not known if it was commonly practiced by families in other classes.[5] In modern Zoroastrianism it is near non-existent, having been noted to have disappeared as an extant practice by the 11th century AD.[5]

Etymology

While the Avestan term xᵛaētuuadaθa is still of ambiguous meaning and function in the Young Avestan texts, it is only later in Middle Persian that the term becomes used in its current form.[5] The earliest use of the word Xwedodah in Middle Persian in the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht inscription at Naqsh-e Rostam.[3] The nineteenth-century qaêtvadatha style (with q instead of Avesta x) and similar writings reappear in modern literature.

The first part of the compound seems to be a "family" (or similar) of Khito (xᵛaētu), which is generally thought to derive from the "self" (xᵛaē-) with the suffix -you (-tu-), although this is not entirely straightforward . The second part, vadaθa, is nowadays generally regarded as a derivative of the verb (From * Wad-) 'resulting in marriage', related to other Iranian and Indo-European languages which refer to marriage or marriage partner (compare with ancient Indik). "Wife" Av. Vaδū; Pahlavi wayūg (Pers. Bayu) "bride"; Avestan vaδut "one who has reached the age of marriage"; Pahlavi wayūdag "bride's room".

This etymology was suggested by Carl Goldner, and accepted by Émile Benveniste and Christian Bartholomae, and became a popular opinion among Western scholars. However, there is no * vadha- to Vedic or * vada- root in the Avesta of the vadh root; in Avesta the vāδaya and upa.vāδaiia- 'lead (to marry)' and uzuuāδaiia are 'leaving the father's house'. vadh-Vedic, vad-Avestan should not be confused with vah-Avestan "to take", vaz-Avestan with the uhyá-unknown form.

Zoroastrian religious sources

Most of Pahlavi's texts are self-contained by Edward William West's comments. Brief evaluations and references include Friedrich Spiegel and standard books on Zoroastrianism, such as Boyce.

Avestan

In the Old Avestan texts known as the Gathas, believed to have been written by the founder of the faith Zoroaster, Armaiti of the Amesha Spenta is referred to as the "daughter" of Ahura Mazda, the highest deity within Zoroastrianism.[6] The Younger Avestan texts of the Yashts, in particular the Frawardin Yasht, mention that the relationship is less a literally familial one and instead one of unity of essence and nature with Ahura Mazda as "father and commander" of the group.[7] In the youngest Avestan text, the Vendidad, the urine of sheep, oxen, and those who marry next-of-kin are viewed as being particularly pure and devoid of corruption by Ahriman and therefore able to be used by corpse-bearers to wash and purify themselves.[8]

Pahlavi

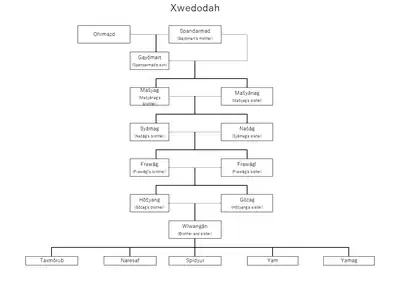

Xwedodah became a more solidified doctrine in the Pahlavi/Middle Persian literature of post-Sassanian Zoroastrianism.[3] In Zoroastrian cosmogony as explained by the Pahlavi text Bundahishn, Ahura Mazda is said to not have sired the other divine creations but rather to have fashioned or set them in their proper places and is referred to as both "mother", through spiritual nurturing, and "father", through material development, of all existence. The Denkard, which includes passages encouraging the action, and the Dadestan-i Denig both claim that not only was the world was created through xwedodah, but rather humanity from the Consanguine marriage of Mashya and Mashyana, who were born from the spiritually-incestuous relationship of Keyumars (produced from xwedodah with Armaiti) and Spenta Armaiti, also developed from it to the pleasure of Ahura Mazda.[5][3][9] In the third book of the Denkard, which consists of a collection of Wisdom literature that can at times contradict itself, regarding an inquiry whether it was appropriate to marry a Hebrew, xwedodah is referred to not as consanguine marriage but rather as marriage within the faith which is viewed as providing honor and strength to those who engage in it and can include incestuous relationships of various kinds.[10] The Revayats, dating from the 1400s as a series of clerical communications, further solidify this broader view of xwedodah while encouraging the incestuous nature of it also noting that the practice had not been extant in centuries and the Shahnameh has it mentioned in passing.[5] According to the revayats, the marriage between a mother and her son is the most superior type of xwedodah, followed by that of father and daughter, which is followed by that of brother and sister. The xwedodah becomes even more superior if the mother/daughter is also the sister of her son/father.[11]

Non-Zoroastrian sources

There are 60 outside sources referencing Zoroastrian Persian brother-sister incest marriages come from the Greeks, Romans, Armenians, Arabians, Indians, Tibetans, and Chinese, ranging from the 5th century BC into the 15th century AD, roughly 2000 years.[1] To maintain stability over a multicultural empire, the Islamic Caliphate allowed newly conquered territory to keep their customs and practices as long as they submitted and paid their taxes.[12] Thus Zoroastrian brother-sister incest continued to persist and exist well into the Middle Ages.[13]

Greco-Roman

Greek sources such as Xanthus of Lydia and Ctesias of Cnidus mentioned that the Magi priesthood have sexual and matrimonial relationships with their relatives while Herodotus states that before Cambyses I this was not a Persian practice. Roman poets Catullus and Ovid both included references to consanginous relationships in the Persian Empire and Quintus Curtius Rufus states in his histories that the Sogdian governor Sisimithres sired two sons from his own mother.[5]

Jewish

Babylonian Jewish rabbis formulated a legal-theoretical interpretation in the Babylonian Talmud on sexual relationships between siblings, forbidden to Jews and permissible to Gentiles (non-Jews), in light of the Zoroastrian doctrine of xwedodah.[14] Philo of Alexandria related that the product of high-born incestuous relationship were themselves considered exaltated and noble, while the Babylonian Talmud notes cases in which situations comparable to xwedodah are both allowed and punishable but without direct mention of Zoroastrianism in the texts.[5]

Islamic

Al-Tha'alibi writes that Zoroaster must have legalized marriage and made them Halal between brothers and sisters and fathers and daughters because Adam had married his sons to his daughters. Al-Masudi reported that Ardashir I told his people to marry close relatives to strengthen family ties. Abū Hayyān al-Tawhīdī declared the historical practice depraved, feebleminded, and deceptive in comparison to Arab practices and noted that it resulted in birth defects and was incorrectly declared a practice not done even by animals.[5] Ibn al-Jawzi states in his Talbis al-Iblis that zoroaster did preach these commandments which was then common between the parsis. Ferdowsi mentions incest between Bahman and his sister Homa.[5]

Christian

Eusebius cites the Gnostic theologian Bardaisan who stated that the Persians brought the practice with them wherever they went and that the Magi priesthood still practiced it by his time while Pseudo-Clement and Basil of Caesarea both commented on the unlawfulness of such practices in comparison to Christian doctrine. Eznik of Kolb accused Zoroaster of having developed the doctrine due to his own desires to see it propagated among his people and Jerome attached the Persians amongst Ethiopians, Medians, and Indians as those who had intercourses with the female members of their families. The Synod of Beth Lapat had proclamations against Christians who imitated the practice of xwedodah with Patriarch Aba I, a convert from Zoroastrianism, championing the cause against the practice.[5]

The most comprehensive reports come from Eastern Christians who lived under Persian rule, they wrote down that these were not just fictitious stories of far away people, but were indeed very real and widely practiced. Iso'bokht, the Nestorian patriarch of the Persis writes many books on this topic urging Christians and other peoples to not practice this custom.[12][1]

Greek

The common feature of non-Iranian sources is that they rarely mention the Iranians themselves, even if they do occasionally mention the majus clerics. Numerous classical sources and later authors point to the incarnation of incest in the Achaemenid monarchies of the Parthian and Sassanian dynasties. Some of the earliest Greek references to non-royal incest are those by Xanthus in his book Magica, which Clement of Alexandria quoted as saying that Magi had sex with their mothers, daughters and sisters, and that Ctesias had mentioned a brother-sister marriage. Herodotus mentions that Cambyses lived with his sister.[5]

Chinese

According to the Chinese traveller Du Huan (fl. 751–762), the religious law of Xun-xun, which refers to a non-Abrahamic religion in the middle east, likely Zoroastrianism or Manichaeism, allowed clan members to intermarry.[15] A reference can be found in the Pahlavi-Chinese bilingual tomb inscriptions in Xi'an, in which the deceased woman, from the Surin family princes, is read in Chinese as "wife" but in Pahlavi's "daughter".

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Scheidel, Walter (1996-09-01). "Brother-sister and parent-child marriage outside royal families in ancient egypt and iran: A challenge to the sociobiological view of incest avoidance?". Ethology and Sociobiology. 17 (5): 319–340. doi:10.1016/S0162-3095(96)00074-X. ISSN 0162-3095.

- ↑ Forrest, Satnam Mendoza; Prods O. Skjærvø (2011). Witches, whores, and sorcerers: the concept of evil in early Iran. Austin. ISBN 978-0-292-73540-8. OCLC 774027576.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 4 Kiel, Yishai (October 2016). "The Pahlavi Doctrine of Xwēdōdah". Sexuality in the Babylonian Talmud. pp. 149–181. doi:10.1017/cbo9781316658802.007. ISBN 9781316658802. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ Drijvers, H.J.W. The Book of the Laws of Countries: Dialogue on Fate of Bardaisan of Edessa, Assen: Van Gorcum, 1965. pp 43-45

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "MARRIAGE ii. NEXT OF KIN: IN ZOROASTRIANISM – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

Quintus Curtius Rufus, in his History of Alexander (8.2.19; comp. mid-1st cent. CE), recounts the story of the Sogdian governor Sisimithres, who married his mother and had two sons with her, remarking that parents there were allowed to have indecent intercourse (stupro coire) with their children (II, pp. 252-53; cf. Boyce and Grenet, p. 8).

- ↑ "AVESTA: YASNA: (English)". www.avesta.org. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ↑ "AVESTA: KHORDA AVESTA (English): Frawardin Yasht (Hymn to the Guardian Angels)". www.avesta.org. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ↑ "AVESTA: VENDIDAD (English): Chapter 8: Funerals and purification, unlawful sex". www.avesta.org. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ↑ Skjærvø, "Next-of-Kin Marriage"; Williams (ed.), The Pahlavi Rivayat, ii, 132–133, n. 4.

- ↑ "DENKARD, Book 3, ch 80-81 (Sanjana, Vol 2)". www.avesta.org. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ↑ Williams, A. V. The Pahlavi RivÄyat Accompanying the Dādestān ī Dēnīg Part I & II.

- 1 2 Choksy, J.K. Zoroastrians in Muslim lran: selected problems of coexistence and interaction during the early medieval period. Iranian Studies 20:17-30, 1987.

- ↑ Sachau, E. Syrische Rechtsbiicher, 3, Berlin: Georg Reimer, 1914.

- ↑ Kiel, Yishai (2015). "Noahide Law and the Inclusiveness of Sexual Ethics: Between Roman Palestine and Sasanian Babylonia". In Porat, Benjamin (ed.). Jewish Law Annual. Vol. 21. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. pp. 61–63. ISBN 978-0-415-74269-6.

- ↑ Wan 2017, p. 14.

Bibliography

- Wan, Lei (2017), The First Chinese Travel Record on the Arab World