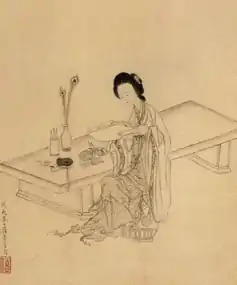

Xue Susu | |

|---|---|

Girl Playing a Jade Flute by Xue Susu, self-portrait[1] | |

| Born | around 1564 |

| Died | 1637 - 1652 |

| Other names | Xue Wu, Xuesu, Sujun, Runqing, Runniang, Wulang |

| Occupation | Yiji |

| Known for | Mounted archery, painting |

| Xue Susu | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 薛素素 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Xue Susu (Chinese: 薛素素; also known as Xue Wu(薛五), Xuesu(薛素), Sujun among other pen names) (c.1564–1650? C.E.) was a Chinese Yiji. Known as one of the "Eight Great Courtesans of the Ming Dynasty", she was an accomplished painter and poet, and was noted for her skill at mounted archery. She was particularly noted for her figure paintings, which included many Buddhist subjects. Her works are held in a number of museums both in China and elsewhere. Her archery was commented upon by a number of contemporary writers, as were her masculine, martial tendencies; these were regarded as an attractive feature by the literati of the period.

She lived in Eastern China, residing for most of her life in the Zhejiang and Jiangsu districts. After a career as a celebrated courtesan in Nanjing, Xue married several times, but none of these unions lasted. During her later life, she eventually opted for the life of a Buddhist recluse.

Biography

Xue was born in either Suzhou or Jiaxing (contemporary sources disagree).[2] According to the historian Qian Qianyi she spent at least some of her childhood in Beijing.[3] She spent her professional life in the Qinhuai pleasure quarter of Nanjing in the 1580s,[4] where she became something of a celebrity among the literati and government officials who frequented the "flower houses" there.[1][2] She was highly selective in her clientele, accepting only learned and scholarly men as her lovers and declining to proffer her affections for mere financial gain; suitors might spend thousands of taels on her to no avail.[1]

In the 1590s she returned to Beijing, where the parties and literary gatherings that she hosted, as well as her archery demonstrations, further cemented her reputation.[5] Xue referred to herself as "a female knight-errant",[2][6] and took her name from a famous woman warrior from history;[3] she also chose the sobriquet Wulang 五郎 ("fifth young gentleman") as a nickname.[5] The "female knight-errant" epithet was reiterated by both the bibliophile Hu Yinglin and Fan Yulin, Secretary to the Ministry of War.[5] Apparently fond of martial causes, she was not above using her position to influence military affairs, on one occasion abandoning her lover Yuan Baode when he refused to fund an expedition against the Japanese in Korea.[2][3]

At some point after 1605 her career as a courtesan came to an end when she married the playwright and bureaucrat Shen Defu.[5] She was married several times (making many of the proposals herself)[7] but none of these unions lasted. As well as Shen Defu, her husbands included General Li Hualong, art critic Li Rihua and, in later life, an unnamed (but wealthy) merchant from Suzhou.[5] Although she wanted children, she was never able to have any.[8]

In later life she converted to Buddhism and remained single thereafter, largely retiring from the world.[1][2] Even in her eighties, however, she was still active in the literary world, entertaining female artists such as Huang Yuanjie and Yi Lin at her home on the West Lake after the collapse of the Ming Dynasty.[1][5] With her Buddhist friend Yang Jiangzi (the sister of Xue's fellow courtesan Liu Yin), she made pilgrimages to sacred sites such as Mount Lu and Mount Emei.[9] The date of her death is uncertain; some sources suggest that she may have lived into the 1650s whilst others put her death in the late 1630s or early 1640s. Qian Qianyi mentions her death in a work published in 1652, so it is evident that she must have died before this date.[5]

Paintings

Already an accomplished painter in her teenage years,[1] Xue was well known for her artistic talent. Her work was considered similar to that of Chen Chun.[10] One of her paintings was considered "the most accomplished work of its kind in the whole of the Ming period",[3] and contemporary art critics regarded her as "a master of technique".[3] Hu Yinglin considered her to be at the pinnacle of contemporary painting, asking, "What famous painter with skilled hands can surpass her?"[2] and claiming that "... [she] surpasses anyone in the painting of bamboo and orchids."[1] She was also keenly admired by eminent painter and art critic Dong Qichang, who was inspired to copy the entire Heart Sutra in response to Xue's painting of the bodhisattva Guanyin;[1] he claimed that "None [of Xue Susu's works] lacks an intention and spirit that approaches the divine."[2] Although she painted the standard subjects of landscapes, bamboo and blossoms (being particularly fond of orchids), Xue was noted for her work in figure painting, which was a comparatively unusual artistic topic for courtesans to address.[1] Examples of her paintings are displayed at the Honolulu Museum of Art and the San Francisco Asian Art Museum.[11]

Poetry

Xue regularly accented her paintings with her own poems, and published two volumes of writing, only one of which is still extant. Hua suo shi Chinese: 花瑣事 (Trifles about Flowers) is a collection of short prose essays and anecdotes about various flowers, whilst Nan you cao Chinese: 南游草 (Notes from a Journey to the South), which has been lost, apparently contained a selection of her poems regarding life as a courtesan. A number of these were collected in various anthologies from the late Ming and early Qing dynasties.[5]

Hu Yinglin wrote that "Her poetry, although lacking in freedom, shows a talent rare among women."[2] Moving in literary circles, Xue also provided the subject matter for many contemporary poets. Xu Yuan, another female poet of the period, describes Xue's allure:

Lotus blossoms as she moves her pair of arches

Her tiny waist, just a hand's breadth, is light enough to dance on a palm

Leaning coyly against the East Wind

Her pure colour and misty daintiness fill the moon.[12]

Hu Yinglin wrote of Xue:

Who transplanted this flower of renowned species to the Imperial garden?

Hers is a smile worth a thousand pieces of gold

She lives near the mooring like Taoye [Peach Leaf], under the wind

She resembles rushes, standing in the water, embracing the moon, and humming

The red phoenix is half-raised because of her mate

Her eyebrows are slightly frowning, expecting a heart to share

This is the moment to read Eternal Regret, the poem of Bo Juyi

Beside the bed, she is awaiting the lute of jade.[1]

Xue's own works deal with a variety of themes, from the mildy erotic:

Inside the city walls of stone in the pleasure quarter

I feel deeply mortified that my talents outshine all the others

The river glitters, the waters clear, and the seagulls swim in pairs

The sky looks hollow, the clouds serene, and the wild geese fly in rows

My embroidered dress partly borrows the hue of hibiscus

The emerald wine shares the scent of lotus

If I did not reciprocate your feelings

Would I dare to feast with you, Master He?[1]

to the romantic:

This lovely night I think of you, wondering whether you will return

The lonely lamp shines on me, casting a faint shadow

I clutch one lone pillow; there is nobody to talk to

Moonlight floods the deserted courtyard; tears soak my dress.[5]

to the whimsically philosophical:

Full of aroma is the taste of wine beneath the bloom

Tinged in azure the gate surrounded by bamboo

In solitude I watch the seagulls fly across the sky

Carefree and content, I feel fully satisfied.[1]

Xue often exchanged poems and paintings with her clientele, receiving their own artworks in exchange.[2]

Archery

Whilst she excelled at poetry, painting and embroidery, the skill that set Xue apart from other courtesans and created a cult of celebrity around her was her talent for archery. Her mastery of a traditionally masculine art gave her an air of androgyny that was considered highly attractive by the literati of the time.[5][9] Having practiced in Beijing as a child[1] she furthered her skills during a sojourn in the company of a military officer in the outlying regions of China. The horsemen of the local tribes there were impressed with her shooting, and she became something of a local celebrity.[3] Later in life she gave public demonstrations in Hangzhou, which drew large audiences.[1][3] Hu Yinglin describes one such performance:

"She is able to shoot two balls from her crossbow one after another and make the second ball strike the first and break it in mid-air. Another trick she can do is to place a ball on the ground, and, by pulling the bow backwards with her left hand, while her right hand draws the bow from behind her back, hit it. Out of a hundred shots, she does not miss a single one.[1]

The poet Lu Bi recalls another trick shot performed by Xue: "When the servant girl takes a ball in her hand and places it on top of her head / She [Xue] turns around, hits it with another ball, and both balls fall to the ground."[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Daria Berg (2008). "Amazon, Artist, and Adventurer: A Courtesan in Late Imperial China". In Kenneth James Hammond; Kristin Eileen Stapleton (eds.). The human tradition in modern China. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 19–30. ISBN 978-0-7425-5466-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Kang-i Sun Chang; Haun Saussy; Charles Yim-tze Kwong (1999). Women writers of traditional China: an anthology of poetry and criticism. Stanford University Press. pp. 227–228. ISBN 978-0-8047-3231-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Victoria B. Cass (1999). Dangerous women: warriors, grannies, and geishas of the Ming. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8476-9395-5.

- ↑ Daria Berg (24 July 2013). Women and the Literary World in Early Modern China, 1580-1700. Routledge. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-1-136-29021-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Berg, Daria (2009). "Cultural Discourse on Xue Susu, A Courtesan in Late Ming China" (PDF). International Journal of Asian Studies. 6 (2): 171–200. doi:10.1017/S1479591409000205. S2CID 145248344. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 7, 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ Alexandra Green (1 February 2013). Rethinking Visual Narratives from Asia: Intercultural and Comparative Perspectives. Editor, Alexandra Green. Hong Kong University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-988-8139-10-1.

- ↑ Lin Foxhall; Gabriele Neher (3 April 2012). Gender and the City before Modernity. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-1-118-23444-0.

- ↑ Richard M. Barnhart; Yang Xin (1997). Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting. Yale University Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-300-09447-3.

- 1 2 Wetzel, J. (2002). "Hidden Connections: Courtesans in the Art World of the Ming Dynasty". Women's Studies. 31 (5): 645–669. doi:10.1080/00497870214051. S2CID 145231141.

- ↑ "Flowers, 1615". Asian Art Museum of San Francisco. Archived from the original on 11 June 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ↑ Helen Tierney (1999). Women's Studies Encyclopedia: A-F. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-313-31071-3.

- ↑ Dorothy Ko (1994). Teachers of the Inner Chambers: Women and Culture in Seventeenth Century China. Stanford University Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-8047-2359-6.

Further reading

- Robinson, James (1988). Views from Jade Terrace: Chinese Women Artists 1300-1912. New York: Indianapolis Museum of Art and Rizzoli. pp. 82–88.