_Womens'_art_class.jpg.webp)

Not until the beginning of the 20th century were university studies fully accessible to women in German-speaking countries, with the exception of Switzerland. The possibility for women to have access to university education, and moreover to obtain a university degree is now part of general higher education for all.

Founding stages of universities / Medieval universities

From the 12th century onwards, universities were first founded based on customary law, then after 1350 universities were also established as the territorial lord's endowment. During these initial stages, the social conditions of the Middle Ages led to the establishment of universities as a purely masculine domaine.[1]

Many universities emerged from cathedral schools for future priests. Therefore, university lecturers belonged to the clergy and had to live in celibacy (only since 1452 have medical doctors been officially allowed to marry). Additionally, students had to go through a basic clerical education in the Seven Liberal Arts in order to continue their studies; graduating from the Faculty of the Arts included a lower ordination. This way women were implicitly excluded from university studies because, due to the oath of secrecy attributed to Paul's first letter to the Corinthians, they were not allowed to be ordained.[2][3]

The Schola Medica Salernitana, which was founded in 1057 and remained a purely medical college, allowed women to study. Names of female medical doctors of this college have been verified. Trota von Salerno for example, presumably at the beginning of the early 12th century, worked as a practical doctor at the school in Salerno. She wrote several treatises on medical practice in general and on gynecology in particular. One of the works published at the Schola Medica Salernitana in the 12th century includes texts from the school's seven masters (magistri), among which Trota's teachings may be found. In the 13th century, a Jewish woman called Rebekka was awarded a doctorate in Salerno as one of the first female doctors ever. Hence, individual schools allowed women to study and teach medicine.[4]

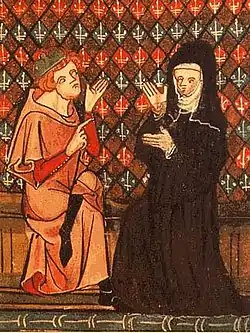

The establishment of universities led to the expansion of the importance and function of the sciences as opposed to the trade apprenticeships. Moreover, academics and scientists developed an identity that linked masculinity with mind and spirit. These polarised images of the genders (men = intellectual beings; women = physical beings) were adopted from medieval theology. Thus, science and femininity were seen as a contradiction.[5] Female skills and knowledge were more and more demonised (witches, poisoners). Women, and especially inquisitive women, were seen as distractions from the sciences for the (intellectual) man and often even as a threat to scholars (compare the story of Abelard and Héloïse as well as Merlin and Viviane).[6] Although, university lecturers and students chose a female scholar as their patron saint, namely Saint Cathrine of Alexandria, according to the legend, Cathrine did not use her knowledge for power or leverage. By rejecting all secular powers, she limited her own options to act.[7]

Soon the universities developed men's societies (so-called Männerbünde) with a corresponding subculture (compare for example the songs of the Carmina Burana). The uncontrolled actions of some students often led to conflicts with the city's inhabitants. Sometimes this could lead to the departure of entire groups of academics who then founded new universities elsewhere. Among the universities' intellectuals many rejected the ideas of clerical celibacy as well as marriage. They saw themselves in a competitive situation with the hereditary nobility, which found its expression in showing off their sexual triumphs and sexual assaults against women. In order to protect the citizens' daughters, the cities set up brothels.[8]

Universities in the 16th to 18th century

Until the 18th century noble and bourgeois sons were educated at universities which were still organised in four faculties: the faculty of Arts, Theology, Medicine and Law, for the education of clergymen, doctors and administrative officials, as well as judges and lawyers.[9] Universities continued to be spaces of male socialization, although celibacy for professors had been abolished and students were no longer living in accommodation reserved for men. This was the result of education for occupations only available to men. Additionally, since the 16th century students had regarded each other as commilitones (brothers-in-arms) and the culture of duels increased.[10][11]

Since there were no generally accepted and binding admission requirements, women were not explicitly banned from studying. Due to the fact that there was no profession a woman could practise after graduating from university, they were left with no real motivation to pursue a course of study. Therefore, women seldom studied at German universities. The few known examples and the circumstances surrounding their studies emphasized the importance of not distracting the male students with their looks. In the seventeenth century Anna Maria van Schurman, for example, participated in lectures at the University of Utrecht, but only from behind a screen on a balcony to protect the male students from seeing her. In the eighteenth century, Luise Adelgunde Victorie Gottsched could only listen to her husband's lectures at the University of Leipzig when hiding behind a half-closed door. In this way, university education was possible for women in individual cases, but the idea of a female professor teaching at German universities was inconceivable.[12]

In the eighteenth century, individual women, in particular the wives and daughters of professors at universities which were open to reform could meet informally with students and professors for an intellectual exchange. For example, many daughters and wives of professors from Göttingen were highly educated compared to other women.[13] Encouraged by her father, who educated his daughter as an experiment, Dorothea Schlözer received a doctorate from the University of Göttingen in 1787. Later, her father concentrated on marrying her to a socially acceptable man.[14] Unlike Schlözer, Dorothea Christiane Erxleben used the authorization given to her by the Prussian king Frederick the Great to complete a degree in medicine. She received her degree on 6 May 1754[15] from the University of Halle, and subsequently practiced as a doctor.[16] These exceptional cases emphasize how in the 18th century completing a course of study and continuing to use the acquired knowledge in their lives only became harder for women. The acquired knowledge was viewed as "unwomanly" and potentially a threat to their reputation. Academic studies endangered women's chances of marriage, but offered no independent professions.[17]

19th century to the end of World War I

The male character of the German university reached its peak in the 19th century. Firstly, at German universities the typical German fraternity-type student associations called Studentenverbindung (such as Corps and Burschenschaften) had developed. These groups often also practiced academic fencing. Simultaneously, a binary gender concept with a gender-specific division of labour had established.

An admissions system that developed in the 19th century was a further peculiarity. In order to study at a university, you needed to have passed the Abitur. Educational patents provided legal rights to particular jobs or study programmes, sometimes even a reduction of compulsory military service. Since there were no girls' schools offering the Abitur (the German leaving certificate) there was an additional obstacle to admission to a German university for women.

In some countries, women were allowed to study in the 19th century. For example, in the US women had been studying at a few colleges since 1833 and in England since 1869. However, there, women only had access to special colleges for women. In France, universities had never really been closed to women. Here, women had been able to obtain academic degrees since the 1860s. Nevertheless, women were not admitted to the Grandes écoles. These elite educational institutions remained restricted to women well into the 20th century. In these countries, full access with equal rights to an academic education was granted about the same time as in the German Reich, where women had been granted equal access right away.

The leading role of Switzerland

In the beginning, women in German-speaking countries were only able to pursue academic studies in Switzerland. The first female auditors were admitted at the University of Zurich in 1840, which had been founded only a few years before. After an application for matriculation of a Russian woman had been unsuccessful in 1864, the application for a doctorate in medicine of Russian Nadezhda Suslova (1843-1918) was approved in 1867, and moreover, she was matriculated as a regular student retroactively.[18][19]

Marie Heim-Vögtlin (1845–1908) was the first female university student from Switzerland admitted in 1874. She also graduated with a degree in medicine.[20] Famous female students from Zurich in the 19th century included, amongst others, the Swiss women Elisabeth Flühmann, Meta von Salis and Emilie Kempin-Spyri, the Russian Vera Figner, the Austrian Helene von Druskowitz, and the Germans Emilie Lehmus, Pauline Rüdin, Franziska Tiburtius, Anita Augspurg, Ricarda Huch and Käthe Schirmacher.

There were different reasons for the pioneering role of Switzerland: In general, university education did not carry a lot of social prestige in Switzerland at this time. Universities tried to attract new students, which ensured their funding by providing additional enrolment fees. Every institution could decide on the admission of women individually. Newer universities, such as Zurich, led by example. However, Switzerland's oldest university, Basel, did not admit women until 1890.[21]

Following the first admissions, the number of students at the University of Zurich increased significantly. In the summer of 1873, 26%, or 114, of the students were female. Most of the female students (109) during this time were from Russia. However, the number of women decreased dramatically in 1873, after the Russian Tsar had prohibited Russian women from studying in Zurich with a Ukase proclamation. Only nine female students were enrolled in winter 1880/81. After the annulment of the Ukase, the number of Russian female students increased again substantially. In the first decade of the 20th century, mainly foreign women from Russia and Germany were studying in Switzerland, only later did more Swiss women enroll.[22]

The dominance of foreign female students was also caused by the fact that, at first, people who were not born in the Canton of Zurich did not need a school leaving certificate for university admission. A "Certificate of Good Conduct" sufficed. Only in 1872 was the minimum age for studying raised to 18, and in 1873 a school leaving certificate became obligatory for all students.[23][24] Since then, many women who had wanted to study prepared for the matriculation examination half a year or a year in advance, after arriving in Zurich. Only after having passed the exam were they allowed to matriculate. However, many women had attended lectures at the university before. Since 1900 only the Swiss have been allowed to register as auditors.[25]

Although women were allowed to study at universities in Switzerland, many students and many professors maintained a hostile attitude towards women's higher education. For example, in 1896, the students council refused a request for women to be allowed to vote in university matters.[26]

Russian female students

On the occasion of Suslowa's enrolment, she wrote home: "I am the first, but not the last. Thousands will come after me." She was right. The Russians were the forerunners for women's studies in Switzerland, but also, they dominated in other European countries until 1914. For this reason, the Russian student typified the image of the female student.

In response to the defeat in the Crimean War, which revealed Russia's backwardness, there were extensive reforms in the country from 1855 on, when the serfdom of peasants was abolished, among other things. There was a close connection between the abolition of serfdom and women's emancipation in the Russian women's movement. A demand for education and medicine grew from social commitment. From 1859, Russians were allowed to attend the Russian universities and the Medical-Surgical Academy as auditors. However, after restructuring of the university's net in 1864, they were denied again. The Russian women then went to study abroad, mainly in Zurich, probably as a result of Suslowa's sensational dissertation. Many Russians who were able to study in Zurich without a high school diploma were poorly prepared for their studies. This discredited women's studies. The lecturers and the local students rejected calling the Russian students "Cossack Horses" because this nickname was insulting. There was no integration. However, despite these difficult conditions, many Russian women studied, and one fifth of the students who were enrolled by 1873 graduated (some in Switzerland, some in other countries).[27]

Many of the Russian students were politically active and in touch with revolutionary societies in Zurich.[28] In a Ukas (decree) on 4 June 1873 the Russian Tsar banned all Russians from studying in Zurich, officially because of moral excesses, but actually because of the anarchist activities of some students. Sanctions and even a prohibition to work were the punishments in case of violation.[29][30] Consequently, the number of Russian students in Zurich dropped dramatically.

On the one hand, the Russian government felt responsible to offer an alternative to returning students. On the other hand, there was a shortage of doctors in Russia, which was especially noticeable in wartime. For this reason "Training courses for qualified midwives" were offered at the Medical-Surgical Academy in St. Petersburg from 1872. Despite the name, these courses fulfilled university standards, so only a part of the female students from Zurich had to move to another Swiss university. The majority went to study in St. Petersburg.[31] After 1881, one by one all educational institutions providing women with higher education were closed, as medically educated women were involved in the assassination of the Russian Tsar. As a result, the second wave of Russian students migrated to Western European universities.

After the inauguration of Tsar Nikolaus II in 1895, Russian politics changed again with regard to women's studies. But even then there were many reasons for Russians wanting to study at Western European universities, namely because of (1) the limited training capacities in the Tsarist empire, (2) fear of political persecution, and (3) the unpredictability of the study situation in Russia (universities were closed at short notice, for example). In addition, since 1886 the number of Russian female students of the Jewish faith could not exceed 3% in any higher education institution. In 1905, the domestic political conditions after the failed attempt at revolution brought a further boost. The number of Russian medical students in Berlin tripled.[32]

The opponents of women's studies in Germany and Switzerland—professors and members of parliament—argued that the Russian Ukas from 1873 portrayed an image of a politically subversive, morally corrupt Russian woman.[33] As a reaction, the German women's movement created a picture of the German student which was the exact opposite of the image of the Russian student. Thus, in 1887 Mathilde Weber asked the German students to deliberately distinguish themselves in appearance, clothing and behaviour from their Russian classmates and prevent their dominance in the female students' associations. The Swiss and German students also kept at distance from their Russian classmates. The accusation of six Swiss students in 1870 to the University of Zurich's Senate that Russians did not have the appropriate level of education was only the beginning of a long series of such protests at Western European universities.[34]

German Empire

Pioneers

The first woman to ever receive a doctor's degree in Germany was Dorothea Erxleben in 1754. She was taught practical medicine by her father, then the Prussian king ordered the University of Halle to register her for the PhD programme. In January 1754 she handed in her dissertation, called 'Academic paper on curing illnesses: much too fast and pleasant but nonetheless frequently uncertain' (''Academische Abhandlung von der gar zu geschwinden und angenehmen, aber deswegen öfters unsicheren Heilung der Krankheiten''). On May 6 she successfully passed the viva. On 26 March 1817, Marianne Theodore Charlotte von Siebold Heidenreich (1788–1859) was awarded a doctorate in childbirth, writing her paper on pregnancy outside the uterus – specifically abdominal pregnancy. (Schwangerschaft außerhalb der Gebärmutter und über Bauchhöhlenschwangerschaft insbesondere) from the University of Giessen. In 1815 her mother Josepha von Siebold, a qualified midwife, had already been awarded in 1815 an honorary doctorate in the same field. In 1827 the French/Swiss author Daniel Jeanne Wyttenbach (1773–1830) was awarded a philosophical honorary doctorate by Marburg University.

Other women who also received a PhD in Germany included Katharina Windscheid (philosophy, 1895 in Heidelberg), Elsa Neumann (physics, 1899 in Berlin), Clara Immerwahr (chemistry, 1900 in Breslau), Dorothea Schlözer (philosophy, 1787, without writing a dissertation), Sofja Kowalewskaja (mathematics, 1874), Julija Wsewolodowna Lermontowa (chemistry, 1874), Margaret Maltby (physical chemistry, 1895), all of them in Göttingen. In 1897 Arthur Kirchhoff[35] published a book called The academic woman: Survey of excellent university professors, teachers of women and writers on the ability of women in academic studies and jobs. (Die Akademische Frau. Gutachten herausragender Universitätsprofessoren, Frauenlehrer und Schriftsteller über die Befähigung der Frau zum wissenschaftlichen Studium und Berufe). Almost half of the 100 opinions were positive. One third, including one from Max Planck, rejected the idea of women studying. Kirchhoff himself mentioned in the preface of his book that he was in favour of universities being accessible to women.[36][37] The book contains a chapter with the 'Records from abroad' where the situation in other countries (United States of America, Belgium, Denmark, England, France, Netherlands, Italy, Russia, Switzerland, Turkey, Hungary) is recounted.

Extending admissions at the end of the 19th century

Since the end of the 19th-century women have been gradually allowed to enrol at German universities. In 1880, Hope Bridges Adams Lehmann, who had attended classes as a guest auditor in medicine, was the first woman to graduate with a Staatsexamen from a German university. However, her degree from the University of Leipzig was not officially recognised. Subsequently, she obtained a doctorate in Bern. In 1881, she received the British licence to practise medicine in Dublin.

The central cause of the women's movement during the time of the German Empire was the improvement of women's education and their access to professions and careers reserved for men. In 1888, the General German Women's Association submitted a petition to the Prussian House of Representatives asking for the admission of women to the studies of medical and academic teaching degrees. In the same year, the German Reformed Women's Association petitioned for the admission of women to all subjects of study, though these initiatives did not achieve any immediate success.

However, individual women achieved exceptions. These exceptions opened a back door to the admission of women at universities – what started as an exception became the rule. The first step had been the admission of women as guest auditors, which had been permitted in Prussia since 1896.[38] This status allowed many women to study. Among them were important figures of the German Empire, such as Helene Stöcker or Gertrud Bäumer. Some women, for example Gertrud Bäumer in 1904, used the opportunity complete their studies with a doctorate.[39]

Between 1852 and 1920, women were not admitted to the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich anymore. Therefore, in order to receive an education in the Fine Arts, future female artists had to enroll at expensive private schools or at newly founded institutions such as the ladies' academy of the Künstlerinnen Verein (1884–1920) or the Debschitz-Schule (1902–1914). However, the Königliche Kunstgewerbeschule, founded in 1868, had allowed women to attend classes since 1872 in a faculty reserved for women. The increase in female students after World War I (as for instance at the University of Würzburg) was criticised and debated in the student body because women were deemed "useless" during times of war. In December 1919, this led to the foundation of the AStA subcommittee for female issues by the student of mathematics Alma Wolffhardt.[40] She tried to dismiss the allegation that women tried to take intellectual advantage of the war.[41] There began a tenacious fight for admissions to the academy, which finally had success in the winter semester 1920/1921. In total 17 women were allowed to enroll and to study under the same conditions as their male peers.

Role of Jewish Women

Most of the female auditors attended the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin. During the first years, there were particularly many Jewish women, especially from the Russian Empire. At the faculty of medicine they even represented the majority of the female students. Many of these women had previously studied in Switzerland and therefore could provide proof of examination at an academic level. One of the arguments to open German universities to women was that Swiss universities had had good experiences with female students. The most famous was Rosa Luxemburg, who had studied economics during the 1890s at the University of Zurich. Other prominent women who studied at Swiss universities included the sisters Hanna and Maria Weizmann, as well as Vera Chazmann, who later on became the wife of Chaim Weizmann.[42] In addition, the philosopher Anna Tumarkin became the first female professor of the University of Bern.[43]

Baden as the model state

On 28 February 1900, the Grand Duchy of Baden was the first German state to issue a decree which allowed women full access to universities. Since 1895 women had been granted revocable rights to pursue academic studies at the faculty of philosophy at the University of Heidelberg. A decisive role had been played by Johanna Kappes, an auditor at the University of Freiburg, who had filed a petition with the state government.[44] In Freiburg, the state's decree was implemented retroactively for the winter term 1899/1900. In addition to Johanna Kappes, four women were admitted to the University of Freiburg as regular students.[45] In Heidelberg, regular admissions for women were implemented in summer semester 1900.[46] Among these women was the Jewish student of medicine and subsequent physician Rahel Straus, who writes about her times as a student in her memoir.[47]

Edith Stein, who obtained a doctorate summa cum laude at the University of Freiburg in 1916, was the first German university assistant with Edmund Husserl in philosophy. Although he later said he believed her capable of pursuing a habilitation, he nonetheless obstructed her career ambitions due to "basic issues". In her habilitation thesis Finite and Infinite Being (Endliches und Ewiges Sein) she had engaged with the works of Husserl and his successor Heidegger.

The situation in Württemberg

On 16 May 1904, the King of Württemberg issued a decree that "women in the German Empire should be able to apply to the University of Tübingen under the same conditions as their male peers". From 1 December 1905 this also applied to the Technische Hochschule Stuttgart.

Prussia

In Prussia, women had been admitted as guest auditors since 1896. Yet women had already been able to study in Prussia with a special permit issued by the minister of education. As early as 1895, 40 women were studying in Berlin and 31 in Göttingen. Overall the admission of women as guest auditors had been a significant improvement to their legal status because they were allowed to obtain a doctorate.[48] In 1908, women were allowed to enroll as regular students at Prussian universities. In 1913 approximately 8% of all students were women. By 1930 their percentage had increased to 16%.

End of World War I to end of World War II

Contrasting developments during National Socialism

After taking over the government, the National Socialists announced they would reduce the percentage of women at universities to 10%. This measure was only partly fulfilled and later secretly revised. In the beginning, access was restricted to prevent the overcrowding of German schools and universities but the law was revised in 1935. The number of students decreased dramatically due to the urgent need to expand the German Armed Forces: there were far fewer than the expected 15,000. 10,538 men and 1,503 women registered in 1934, which led to a shortage of young academics although, since 1936 the number of women at German universities had actually been growing. Women's studies were even promoted from 1938 onwards. During WWII the number of female students increased considerably and proportionally, setting new records in 1943; of the 25,000 students, 50% were women. This ratio was not realized again until 1995. Even in natural science classes the majority of the students were women.[49] In 1934 Austria introduced a numerus clausus of 10% with various limitations and obstacles to admission, which brought about a major change. Even though the number of female students increased as of 1939 due to the war, only after 1945 were laws regarding equality of students established.[50]

References

- ↑ Bea Lundt: Zur Entstehung der Universität als Männerwelt. In: Elke Kleinau, Claudia Opitz (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Mädchen- und Frauenbildung. Bd. 1: Vom Mittelalter bis zur Aufklärung. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 1996. S. 103–118, 484–488, 550–551.

- ↑ Britta-Juliane Kruse: Frauenstudium, medizinisches. 2005, S. 435.

- ↑ Bea Lundt: Zur Entstehung der Universität als Männerwelt. S. 109–110.

- ↑ Richard Landau: Geschichte der jüdischen Ärzte. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Medicin. Berlin 1895, S. 30 (sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de); Ingrid Oberndorfer: Jüdische Ärztinnen im Mittelalter. In: David. Jüdische Kulturzeitschrift. Heft Nr. 56, Wien 2003.

- ↑ Bea Lundt: Zur Entstehung der Universität als Männerwelt. S. 110–111.

- ↑ Bea Lundt: Zur Entstehung der Universität als Männerwelt. S. 116–118.

- ↑ Bea Lundt: Zur Entstehung der Universität als Männerwelt. S. 114–115.

- ↑ Bea Lundt: Zur Entstehung der Universität als Männerwelt. S. 111–113.

- ↑ Beatrix Niemeyer: Ausschluss oder Ausgrenzung? Frauen im Umkreis der Universitäten im 18. Jahrhundert. In: Elke Kleinau, Claudia Opitz (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Mädchen- und Frauenbildung. Bd. 1: Vom Mittelalter bis zur Aufklärung. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 1996. S. 275–294, 512–514, 559; hier S. 276.

- ↑ Beatrix Niemeyer: Ausschluss oder Ausgrenzung? S. 277.

- ↑ Trude Maurer: Einführung: Von der Gleichzeitigkeit des Ungleichzeitigen: Das deutsche Frauenstudium im internationalen Kontext. In: Trude Maurer (Hrsg.): Der Weg an die Universität. Höhere Frauenstudien vom Mittelalter bis zum 20. Jahrhundert. Wallstein, Göttingen 2010. S. 7–22; hier S. 10.

- ↑ Beatrix Niemeyer: Ausschluss oder Ausgrenzung? S. 280–283.

- ↑ Beatrix Niemeyer: Ausschluss oder Ausgrenzung? S. 283–284.

- ↑ Beatrix Niemeyer: Ausschluss oder Ausgrenzung? S. 286–288.

- ↑ Gisela Kaiser: Über die Zulassung von Frauen zum Studium der Medizin am Beispiel der Universität Würzburg. In: Würzburger medizinhistorische Mitteilungen. Band 14, 1996, S. 173–184; hier: S. 173.

- ↑ Beatrix Niemeyer: Ausschluss oder Ausgrenzung? S. 288–290.

- ↑ Beatrix Niemeyer: Ausschluss oder Ausgrenzung? S. 293–294.

- ↑ Hartmut Gimmler: Der Pflanzenphysiologe Julius von Sachs (1832–1897) und das Frauenstudium. In: Würzburger medizinhistorische Mitteilungen. 24, 2005, S. 415–424; hier: S. 415–417 und 420.

- ↑ Franziska Rogger, Monika Bankowski: Ganz Europa blickt auf uns! Das schweizerische Frauenstudium und seine russischen Pionierinnen. Hier + Jetzt, Baden 2010. S. 27.

- ↑ Doris Stump: Zugelassen und ausgegrenzt. In: Verein Feministische Wissenschaft Schweiz (Hrsg.): Ebenso neu als kühn. 120 Jahre Frauenstudium an der Universität Zürich. Efef, Zürich 1988. S. 15–28; hier S. 16.

- ↑ Trude Maurer: Von der Gleichzeitigkeit des Ungleichzeitigen. S. 14–15.

- ↑ Regula Schnurrenberger, Marianne Müller: Ein Überblick. In: Verein Feministische Wissenschaft Schweiz (Hrsg.): Ebenso neu als kühn. 120 Jahre Frauenstudium an der Universität Zürich. Efef, Zürich 1988. S. 195–207; hier S. 197.

- ↑ Gabi Einsele: Kein Vaterland. Deutsche Studentinnen im Zürcher Exil (1870–1908). In: Anne Schlüter (Hrsg.): Pionierinnen – Feministinnen – Karrierefrauen? Zur Geschichte des Frauenstudiums in Deutschland. Frauen in Geschichte und Gesellschaft Bd. 22. Centaurus, Pfaffenweiler 1992. S. 9–34; hier S. 11.

- ↑ Elke Rupp: Der Beginn des Frauenstudiums an der Universität Tübingen. Werkschriften des Universitätsarchivs Tübingen / Quellen und Studien, Bd. 4. Universitätsarchiv, Tübingen 1978. S. 15.

- ↑ Gabi Einsele: Kein Vaterland. S. 21, 27.

- ↑ Gabi Einsele: Kein Vaterland. S. 26–27.

- ↑ Monika Bankowski-Züllig: Zürich – das russische Mekka. In: Verein Feministische Wissenschaft Schweiz (Hrsg.): Ebenso neu als kühn. 120 Jahre Frauenstudium an der Universität Zürich. Efef, Zürich 1988, S. 127–128; hier S. 127.

- ↑ Anja Burchardt (1997), Blaustrumpf – Modestudentin – Anarchistin? Deutsche und russische Medizinstudentinnen in Berlin 1896–1918 (in German), Stuttgart: Metzler, p. 52

- ↑ Elke Rupp: Der Beginn des Frauenstudiums an der Universität Tübingen. 1978, S. 15.

- ↑ Gabi Einsele: Kein Vaterland. 1992, S. 12.

- ↑ Anja Burchardt (1997), Blaustrumpf – Modestudentin – Anarchistin? (in German), pp. 52–53

- ↑ Anja Burchardt (1997), Blaustrumpf – Modestudentin – Anarchistin? (in German), pp. 56–60

- ↑ Anja Burchardt (1997), Blaustrumpf – Modestudentin – Anarchistin? (in German), pp. 67–73

- ↑ Anja Burchardt (1997), Blaustrumpf – Modestudentin – Anarchistin? (in German), pp. 79–92

- ↑ Arthur Kirchhoff: Die Akademische Frau. Gutachten herausragender Universitätsprofessoren, Frauenlehrer und Schriftsteller über die Befähigung der Frau zum wissenschaftlichen Studium und Berufe. 1897, S. 357 (online [retrieved 29 February 2012] Das Buch wurde 1897 und nicht, wie bei Lanz u. a. fälschlich angegeben, 1887 herausgegeben).

- ↑ Karl Lenz: Entgrenztes Geschlecht. Zu den Grenzen des Konstruktivismus. In: Karl Lenz, Werner Schefold, Wolfgang Schröer: Entgrenzte Lebensbewältigung: Jugend, Geschlecht und Jugendhilfe. S. 83. Juventa 2004.Google Books

- ↑ Lenz, Auszüge aus dem Buch in Englisch. (10 June 2015 via Internet Archive). (PDF; 1,09 MB)

- ↑ Helene Lange, Gertrud Bäumer: Handbuch der Frauenbewegung. Moeser, Berlin 1901, S. 96 f.

- ↑ Angelika Schaser: Helene Lange und Gertrud Bäumer. Eine politische Lebensgemeinschaft. Böhlau, Köln 2010, pp. 103–106.

- ↑ Alma Wolffhardt: Frauenstudium. In: Würzburger Universitätszeitung. Band 1, 1919, S. 110–113.

- ↑ Walter Ziegler: Die Universität Würzburg im Umbruch (1918–20). In Peter Baumgart (ed.): Vierhundert Jahre Universität Würzburg. Eine Festschrift. Degener & Co. (Gerhard Gessner), Neustadt an der Aisch 1982 (= Quellen und Beiträge zur Geschichte der Universität Würzburg. Band 6), ISBN 3-7686-9062-8, pp. 179–251; hier: S. 222 f.

- ↑ Hartmut Gimmler, S. 417.

- ↑ Luise Hirsch: Vom Schtetl in den Hörsaal: Jüdische Frauen und Kulturtransfer. Metropol, Berlin 2010.

- ↑ Ernst Theodor Nauck (1953), Das Frauenstudium an der Universität Freiburg i.Br. (in German), Freiburg, p. 21

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Grete Borgmann (1973), Freiburg und die Frauenbewegung (in German), Ettenheim/Baden, p. 23

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Vor einhundert Jahren Beginn des Frauenstudiums an der Universität Freiburg. Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg im Breisgau, 23 February 2000.

- ↑ Wir lebten in Deutschland. DVA, Stuttgart 1961.

- ↑ Helene Lange, Gertrud Bäumer: Handbuch der Frauenbewegung. Moeser, Berlin 1901, S. 98 f.

- ↑ Claudia Huerkamp: Bildungsbürgerinnen. Frauen im Studium und in akademischen Berufen 1900–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1996.

- ↑ Der mühsame Weg der Frauen an die Unis. (1 December 2005 via Internet Archive).